- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Magna Carta

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 9, 2023 | Original: December 17, 2009

By 1215, thanks to years of unsuccessful foreign policies and heavy taxation demands, England’s King John was facing down a possible rebellion by the country’s powerful barons. Under duress, he agreed to a charter of liberties known as the Magna Carta (or Great Charter) that would place him and all of England’s future sovereigns within a rule of law.

Though it was not initially successful, the document was reissued (with alterations) in 1216, 1217 and 1225, and eventually served as the foundation for the English system of common law. Later generations of Englishmen would celebrate the Magna Carta as a symbol of freedom from oppression, as would the Founding Fathers of the United States of America, who in 1776 looked to the charter as a historical precedent for asserting their liberty from the English crown.

Background and Context

John (the youngest son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine ) was not the first English king to grant concessions to his citizens in the form of a charter, though he was the first one to do so under threat of civil war. Upon taking the throne in 1100, Henry I had issued a Coronation Charter in which he promised to limit taxation and confiscation of church revenues, among other abuses of power. But he went on to ignore these precepts, and the barons lacked the power to enforce them. They later gained more leverage, however, as a result of the English crown’s need to fund the Crusades and pay a ransom for John’s brother and predecessor, Richard I (known as Richard the Lionheart ), who was taken prisoner by Emperor Henry VI of Germany during the Third Crusade.

Did you know? Today, memorials stand at Runnymede to commemorate the site's connection to freedom, justice and liberty. In addition to the John F. Kennedy Memorial, Britain's tribute to the 35th U.S. president, a rotunda built by the American Bar Association stands as "a tribute to Magna Carta, symbol of freedom under law."

In 1199, when Richard died without leaving an heir, John was forced to contend with a rival for succession in the form of his nephew Arthur (the young son of John’s deceased brother Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany). After a war with King Philip II of France, who supported Arthur, John was able to consolidate power. He immediately angered many former supporters with his cruel treatment of prisoners (including Arthur, who was probably murdered on John’s orders). By 1206, John’s renewed war with France had caused him to lose the duchies of Normandy and Anjou, among other territories.

Who Signed the Magna Carta and Why?

A feud with Pope Innocent III, beginning in 1208, further damaged John’s prestige, and he became the first English sovereign to suffer the punishment of excommunication (later meted out to Henry VIII and Elizabeth I ). After another embarrassing military defeat by France in 1213, John attempted to refill his coffers–and rebuild his reputation–by demanding scutage (money paid in lieu of military service) from the barons who had not joined him on the battlefield. By this time, Stephen Langton, whom the pope had named as archbishop of Canterbury over John’s initial opposition, was able to channel baronial unrest and put increasing pressure on the king for concessions.

With negotiations stalled early in 1215, civil war broke out, and the rebels–led by baron Robert FitzWalter, John’s longtime adversary–gained control of London. Forced into a corner, John yielded, and on June 15, 1215, at Runnymede (located beside the River Thames, now in the county of Surrey), he accepted the terms included in a document called the Articles of the Barons. Four days later, after further modifications, the king and the barons issued a formal version of the document, which would become known as the Magna Carta. Intended as a peace treaty, the charter failed in his goals, as civil war broke out within three months.

After John’s death in 1216, advisors to his nine-year-old son and successor, Henry III, reissued the Magna Carta with some of its most controversial clauses taken out, thus averting further conflict. The document was reissued again in 1217 and once again in 1225 (in return for a grant of taxation to the king). Each subsequent issue of the Magna Carta followed that “final” 1225 version.

How Did Magna Carta Influence the U.S. Constitution?

The 13th‑century pact inspired the U.S. Founding Fathers as they wrote the documents that would shape the nation.

6 Things You May Not Know About Magna Carta

Six fascinating facts about the Great Charter's story and its significance.

How the US Constitution Has Changed and Expanded Since 1787

Through amendments and legal rulings, the Constitution has transformed in some critical ways.

What Did the Magna Carta Do?

Written in Latin, the Magna Carta (or Great Charter) was effectively the first written constitution in European history. Of its 63 clauses, many concerned the various property rights of barons and other powerful citizens, suggesting the limited intentions of the framers. The benefits of the charter were for centuries reserved for only the elite classes, while the majority of English citizens still lacked a voice in government.

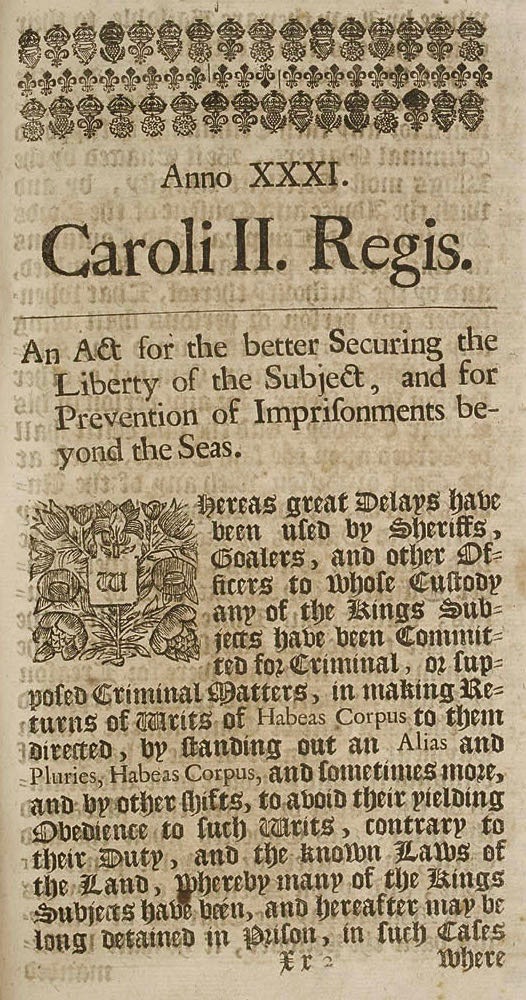

In the 17th century, however, two defining acts of English legislation–the Petition of Right (1628) and the Habeas Corpus Act (1679)–referred to Clause 39, which states that “no free man shall be…imprisoned or disseised [dispossessed]… except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” Clause 40 (“To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice”) also had dramatic implications for future legal systems in Britain and America.

In 1776, rebellious American colonists looked to the Magna Carta as a model for their demands of liberty from the English crown on the eve of the American Revolution . Its legacy is especially evident in the Bill of Rights and the U.S. Constitution , and nowhere more so than in the Fifth Amendment (“Nor shall any persons be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law”), which echoes Clause 39. Many state constitutions also include ideas and phrases that can be traced directly to the historic document.

Where Is the Original Magna Carta?

Four original copies of the Magna Carta of 1215 exist today: one in Lincoln Cathedral, one in Salisbury Cathedral, and two in the British Museum.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

1215: Magna Carta (Latin and English)

- Magna Carta

- Magna Carta: A Commentary (1914)

- Subject Area: Law

Source: The Roots of Liberty: Magna Carta, Ancient Constitution, and the Anglo-American Tradition of Rule of Law , edited and with an Introduction by Ellis Sandoz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2008). Appendix: Text and Translation of Magna Carta

Copyright: The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc.

Fair Use: This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Appendix: Text and Translation of Magna Carta *

There follows the text in Latin and in English translation of Magna Carta of 1225, the third Great Charter of Henry III. This is the definitive version that received statutory confirmation by Edward I in 1297, thereby entering the Statutes of the Realm as the first English statute. Thus, it is the Great Charter ultimately relied upon by Sir Edward Coke, John Selden, and the other great common lawyers of the seventeenth century. By then, according to Coke, it had been confirmed at least thirty-two times.

THE GREAT CHARTER OF HENRY III

(Third Revision, Issued February 11, 1225)

Henricus Dei gratia rex Anglie, dominus Hibernie, dux Normannie, Aquitanie, et comes Andegavie, archiepiscopis, episcopis, abbatibus, prioribus, comitibus, baronibus, vicecomitibus, prepositis, ministris et omnibus ballivis et fidelibus suis presentem cartam inspecturis, salutem. Sciatis quod nos, intuitu Dei et pro salute anime nostre et animarum antecessorum et successorum nostrorum, ad exaltationem sancte ecclesie et emendationem regni nostri, spontanea et bona voluntate nostra, dedimus et concessimus archiepiscopis, episcopis, abbatibus, prioribus, comitibus, baronibus et omnibus de regno nostro has libertates subscriptas tenendas in regno nostro Anglie in perpetuum.

1 (1). In primis concessimus Deo et hac presenti carta nostra confirmavimus pro nobis et heredibus nostris in perpetuum quod anglicana ecclesia libera sit, et habeat omnia jura sua integra et libertates suas illesas. Concessimus etiam omnibus liberis hominibus regni nostri pro nobis et heredibus nostris in perpetuum omnes libertates subscriptas, habendas et tenendas eis et heredibus suis de nobis et heredibus nostris in perpetuum.

2 (2). Si quis comitum vel baronum nostrorum sive aliorum tenencium de nobis in capite per servicium militare mortuus fuerit, et, cum decesserit, heres ejus plene etatis fuerit et relevium debeat, habeat hereditatem suam per antiquum relevium, scilicet heres vel heredes comitis de baronia comitis integra per centum libras, heres vel heredes baronis de baronia integra per centum libras, heres vel heredes militis de feodo militis integro per centum solidos ad plus; et qui minus debuerit minus det secundum antiquam consuetudinem feodorum.

3 (3). Si autem heres alicujus talium fuerit infra etatem, dominus ejus non habeat custodiam ejus nec terre sue antequam homagium ejus ceperit; et, postquam talis heres fuerit in custodia, cum ad etatem pervenerit, scilicet viginti et unius anni, habeat hereditatem suam sine relevio et sine fine, ita tamen quod, si ipse, dum infra etatem fuerit, fiat miles, nichilominus terra remaneat in custodia dominorum suorum usque ad terminum predictum.

4 (4). Custos terre hujusmodi heredis qui infra etatem fuerit non capiat de terra heredis nisi rationabiles exitus et rationabiles consuetudines et rationabilia servicia, et hoc sine destructione et vasto hominum vel rerum; et si nos commiserimus custodiam alicujus talis terre vicecomiti vel alicui alii qui de exitibus terre illius nobis debeat respondere, et ille destructionem de custodia fecerit vel vastum, nos ab illo capiemus emendam, et terra committetur duobus legalibus et discretis hominibus de feodo illo qui de exitibus nobis respondeant vel ei cui eos assignaverimus; et si dederimus vel vendiderimus alicui custodiam alicujus talis terre, et ille destructionem inde fecerit vel vastum, amittat ipsam custodiam et tradatur duobus legalibus et discretis hominibus de feodo illo qui similiter nobis respondeant, sicut predictum est.

5 (5). Custos autem, quamdiu custodiam terre habuerit, sustentet domos, parcos, vivaria, stagna, molendina et cetera ad terram illam pertinencia de exitibus terre ejusdem, et reddat heredi, cum ad plenam etatem pervenerit, terram suam totam instauratam de carucis et omnibus aliis rebus, ad minus secundum quod illam recepit. Hec omnia observentur de custodiis archiepiscopatuum, episcopatuum, abbatiarum, prioratuum, ecclesiarum et dignitatum vacancium que ad nos pertinent, excepto quod hujusmodi custodie vendi non debent.

6 (6). Heredes maritentur absque disparagatione.

7 (7). Vidua post mortem mariti sui statim et sine difficultate aliqua habeat maritagium suum et hereditatem suam, nec aliquid det pro dote sua vel pro maritagio suo vel pro hereditate sua, quam hereditatum maritus suus et ipsa tenuerunt die obitus ipsius mariti, et maneat in capitali mesagio mariti sui per quadranginta dies post obitum ipsius mariti sui, infra quos assignetur ei dos sua, nisi prius et fuerit assignata, vel nisi domus illa sit castrum; et si de castro recesserit, statim provideatur ei domus competens in qua possit honeste morari, quousque doe sua ei assignetur secundum quod predictum est, et habeat rationabile estoverium suum interim de communi. Assignetur autem ei pro dote sua tercia pars tocius terre mariti sui que sua fuit in vita sua, nisi de minori dotata fuerit ad hostium ecclesie.

(8). Nulla vidua distringatur ad se maritandam, dum vivere voluerit sine marito, ita tamen quod securitatem faciet quod se non maritabit sine assensu nostro, si de nobis tenuerit, vel sine assensu domini sui, si de aliquo tenuerit.

8 (9). Nos vero vel ballivi nostri non seisiemus terram aliquam nec redditum pro debito aliquo quamdiu catalla debitoris presencia sufficiant ad debitum reddendum et ipse debitor paratus sit inde satisfacere; nec plegii ipsius debitoris distringantur quamdiu ipse capitalis debitor sufficiat ad solutionem debiti; et, si capitalis debitor defecerit in solutione debiti, non habens unde reddat aut reddere rolit cum possit, plegii respondeant pro debito; et, si voluerint, habeant terras et redditus debitoris quousque sit eis satisfactum de debito quod ante pro eo solverunt, nisi capitalis debitor monstraverit se inde esse quietum versus eosdem plegios.

9 (13). Civitas Londonie habeat omnes antiquas libertates et liberas consuetudines suas. Preterea volumus et concedimus quod omnes alie civitates, et burgi, et ville, et barones de quinque portubus, et omnes portus, habeant omnes libertates et liberas consuetudines suas.

10 (16). Nullus distringatur ad faciendum majus servicium de feodo militis nec de alio libero tenemento quam inde debetur.

11 (17). Communia placita non sequantur curiam nostram, set teneantur in aliquo loco certo.

12 (18). Recognitiones de nova disseisina et de morte antecessoris non capiantur nisi in suis comitatibus, et hoc modo: nos, vel si extra regnum fuerimus, capitalis justiciarius noster, mittemus justiciarios per unumquemque comitatum semel in anno, qui cum militibus comitatuum capiant in comitatibus assisas predictas. Et ea que in illo adventu suo in comitatu per justiciarios predictos ad dictas assisas capiendas missos terminari non possunt, per eosdem terminentur alibi in itinere suo; et ea que per eosem propter difficultatem aliquorum articulorum terminari non possunt, refer-antur ad justiciarios, nostros de banco, et ibi terminentur.

13. Assise de ultima presentatione semper capiantur coram justiciariis nostris de banco et ibi terminentur.

14 (20). Liber homo non amercietur pro parvo delicto nisi secundum modum ipsius delicti, et pro magno delicto, secundum magnitudinem delicti, salvo contenemento suo; et mercator eodem modo salva mercandisa sua; et villanus alterius quam noster eodem modo amercietur salvo wainagio suo, si inciderit in misericordiam nostram; et nulla predictarum misericordiarum ponatur nisi per sacramentum proborum et legalium hominum de visneto.

(21). Comites et barones non amercientur nisi per pares suos, et non nisi secundum modum delicti.

(22). Nulla ecclesiastica persona amercietur secundum quantitatem beneficii sui ecclesiastici, set secundum laicum tenementum suum, et secundum quantitatem delicti.

15 (23). Nec villa, nec homo, distringatur facere pontes ad riparias nisi que ex antiquo et de jure facere debet.

16. Nulla riparia decetero defendatur, nisi ille que fuerunt in defenso tempore regis Henrici avi nostri, per eadem loca et eosdem terminos sicut esse consueverunt tempore suo.

17 (24). Nullus vicecomes, constabularius, coronatores vel alii ballivi nostri teneant placita corone nostre.

18 (26). Si aliquis tenens de nobis laicum feodum moriatur, et vice-comes vel ballivus noster ostendat litteras nostras patentes de summonitione nostra de debito quod defunctus nobis debuit, liceat vicecomiti vel ballivo nostro attachiare et inbreviare catalla defuncti inventa in laico feodo ad valenciam illius debiti per visum legalium hominum, ita tamen quod nichil inde amoveatur donec persolvatur nobis debitum quod clarum fuerit, et residuum relinquatur executoribus ad faciendum testamentum defuncti; et si nichil nobis debeatur ab ipso, omnia catalla cedant defuncto, salvis uxori ipsius et pueris suis rationabilibus partibus suis.

19 (28). Nullus constabularius vel ejus ballivus capiat blada vel alia catalla alicujus qui non sit de villa ubi castrum situm est, nisi statim inde reddat denarios aut respectum inde habere possit de voluntate venditoris; si autem de villa ipsa fuerit, infra quadraginta dies precium reddat.

20 (29). Nullus constabularius distringat aliquem militem ad dandum denarios pro custodia castri, si ipse eam facere voluerit in propria persona sua, vel per alium probum hominem, si ipse eam facere non possit propter rationabilem causam, et, si nos duxerimus eum vel miserimus in exercitum, erit quietus de custodia secundum quantitatem temporis quo per nos fuerit in exercitu de feodo pro quo fecit servicium in exercitu.

21 (30). Nullus vicecomes, vel ballivus noster, vel alius capiat equos vel carettas alicujus pro cariagio faciendo, nisi reddat liberationem antiquitus statutam, scilicet pro caretta ad duos equos decem denarios per diem, et pro caretta ad tres equos quatuordecim denarios per diem. Nulla caretta dominica alicujus ecclesiastice persone vel militis vel alicujus domine capiatur per ballivos predictos.

(31). Nec nos nec ballivi nostri nec alii capiemus alienum boscum ad castra vel alia agenda nostra, nisi per voluntatem illius cujus boscus ille fuerit.

22 (32). Nos non tenebimus terras eorum qui convicti fuerint de felonia, nisi per unum annum et unum diem; et tunc reddantur terre dominis feodorum.

23 (33). Omnes kidelli decetero deponantur penitus per Tamisiam et Medeweiam et per totam Angliam, nisi per costeram maris.

24 (34). Breve quod vocatur Precipe decetero non fiat alicui de aliquo tenamento, unde liber homo perdat curiam suam.

25 (35). Una mensura vini sit per totum regnum nostrum, et una mensura cervisie, et una mensura bladi, scilicet quarterium London, et una latitudo pannorum tinctorum et russettorum et haubergettorum, scilicet due ulne infra listas; de ponderibus vero sit ut de mensuris.

26 (36). Nichil detur de cetero pro brevi inquisitionis ab eo qui inquisitionem petit de vita vel membris, set gratis concedatur et non negetur.

27 (37). Si aliquis teneat de nobis per feodifirmam vel soccagium, vel per burgagium, et de alio terram teneat per servicium militare, nos non habebimus custodiam heredis nec terre sue que est de feodo alterius, occasione illius feodifirme, vel soccagii, vel burgagii, nec habebimus custodiam illius feodifirme vel soccagii vel burgagii, nisi ipsa feodifirma debeat servicium militare. Nos non habebimus custodiam heredis nec terre alicujus quam tenet de alio per servicium militare, occasione alicujus parve serjanterie quam tenet de nobis per servicium reddendi nobis cultellos, vel sagittas, vel hujusmodi.

28 (38). Nullus ballivus ponat decetero aliquem ad legem manifestam vel ad juramentum simplici loquela sua, sine testibus fidelibus ad hoc inductis.

29 (39). Nullus liber homo decetero capiatur vel imprisonetur aut disseisiatur de aliquo libero tenemento suo vel libertatibus vel liberis consuetudinibus suis, aut utlagetur, aut exuletur aut aliquo alio modo destruatur, nec super eum ibimus, nec super eum mittemus, nisi per legale judicium parium suorum, vel per legem terre.

(40). Nulli vendemus, nulli negabimus aut differemus rectum vel justiciam.

30 (41). Omnes mercatores, nisi publice antea prohibiti fuerint, habeant salvum et securum exire de Anglia, et venire in Angliam, et morari, et ire per Angliam tam per terram quam per aquam ad emendum vel vendendum sine omnibus toltis malis per antiquas et rectas consuetudines, preterquam in tempore gwerre, et si sint de terra contra nos gwerrina; et si tales inveniantur in terra nostra in principio gwerre, attachientur sine dampno corporum vel rerum, donec sciatur a nobis vel a capitali justiciario nostro quomodo mercatores terre nostre tractentur, qui tunc invenientur in terra contra nos gwerrina; et, si nostri salvi sint ibi, alii salvi sint in terra nostra.

31 (43). Si quis tenuerit de aliqua escaeta, sicut de honore Wallingefordie, Bolonie, Notingeham, Lancastrie, vel de aliis que sunt in manu nostra, et sint baronie, et obierit, heres ejus non det aliud relevium nec fiat nobis aliud servicium quam faceret baroni, si ipsa esset in manu baronis; et nos eodem modo eam tenebimus quo baro eam tenuit, nec nos, occasione talis baronie vel escaete, habebimus aliquam escaetam vel custodiam aliquorum hominum nostrorum, nisi alibi tenuerit de nobis in capite ille qui tenuit baroniam vel escaetam.

32. Nullus liber homo decetero det amplius alicui vel vendat de terra sua quam ut de residuo terre sue possit sufficienter fieri domino feodi servicium ei debitum quod pertinet ad feodum illud.

33 (46). Omnes patroni abbatiarum qui habent cartas regum Anglie de advocatione, vel antiquam tenuram vel possessionem, habeant earum custodiam cum vacaverint, sicut habere debent, et sicut supra declaratum est.

34 (54). Nullus capiatur vel imprisonetur propter appellum femine de morte alterius quam viri sui.

35. Nullus comitatus decetero teneatur, nisi de mense in mensem; et, ubi major terminus esse solebat, major sit. Nec aliquis vicecomes vel ballivus faciat turnum suum per hundredum nisi bis in anno et non nisi in loco debito et consueto, videlicet semel post Pascha et iterum post festum sancti Michaelis. Et visus de franco plegio tunc fiat ad illum terminum sancti Michalis sine occasione, ita scilicet quod quilibet habeat libertates suas quas habuit et habere consuevit tempore regis Henrici avi nostri, vel quas postea perquisivit. Fiat autem visus de franco plegio sic, videlicet quod pax nostra teneatur, et quod tethinga integra sit sicut esse consuevit, et quod vicecomes non querat occasiones, et quod contintus sit eo quod vicecomes habere consuevit de visu suo faciendo tempore regis Henrici avi nostri.

36. Non liceat alicui decetero dare terram suam alicui domui religiose, ita quod eam resumat tenendam de eadem domo, nec liceat alicui domui religiose terram alicujus sic accipere quod tradat illam ei a quo ipsam recepit tenendam. Si quis autem de cetero terram suam alicui domui religiose sic dederit, et super hoc convincatur, donum suum penitus cassetur, et terra illa domino suo illius feodi incurratur.

37. Scutagium decetero capiatur sicut capi solebat tempore regis Henrici avi nostri. Et salve sint archiepiscopis, episcopis, abbatibus, prioribus, templariis, hospitalariis, comitibus, baronibus et omnibus aliis tam ecclesiasticis quam secularibus personis libertates et libere consuetudines quas prius habuerunt.

(60). Omnes autem istas consuetudines predictas et libertates quas concessimus in regno nostro tenendas quantum ad nos pertinet erga nostros, omnes de regno nostro tam clerici quam laici observent quantum ad se pertinet erga suos. Pro hac autem concessione et donatione libertatum istarum et aliarum libertatum contentarum in carta nostra de libertatibus foreste, archiepiscopi, episcopi, abbates, priores, comites, barones, milites, libere tenentes, et omnes de regno nostro dederunt nobis quintam decimam partem omnium mobilium suorum. Concessimus etiam eisdem pro nobis et heredibus nostris quod nec nos nec heredes nostri aliquid perquiremus per quod libertates in hac carta contente infringantur vel infirmentur; et, si de aliquo aliquid contra hoc perquisitum fuerit, nichil valeat et pro nullo habeatur.

His testibus domino Stephano Cantuariensi archiepiscopo, Eustachio Lundoniensi, Jocelino Bathoniensi, Petro Wintoniensi, Hugoni Lincolniensi, Ricardo Sarrisberiensi, Benedicto Roffensi, Willelmo Wigorniensi, Johanne Eliensi, Hugone Herefordiensi, Radulpho Cicestriensi, Willelmo Exoniensi episcopis, abbate sancti Albani, abbate sancti Edmundi, abbate de Bello, abbate sancti Augustini Cantuariensis, abbate de Evashamia, abbate de Westmonasterio, abbate de Burgo sancti Petri, abbate Radingensi, abbate Abbendoniensi, abbate de Maumeburia, abbate de Winchecomba, abbate de Hida, abbate de Certeseia, abbate de Sire-burnia, abbate de Cerne, abbate de Abbotebiria, abbate de Middletonia, abbate de Seleby, abbate de Wyteby, abbate de Cirencestria, Huberto de Burgo justiciario, Ranulfo comite Cestrie et Lincolnie, Willelmo comite Sarrisberie, Willelmo comite Warennie, Gilberto de Clara comite Gloucestrie et Hertfordie, Willelmo de Ferrariis comite Derbeie, Willelmo de Mandevilla comite Essexie, Hugone Le Bigod comite Norfolcie, Willelmo comite Aubemarle, Hunfrido comite Herefordie, Johanne constabulario Cestrie, Roberto de Ros, Roberto filio Walteri, Roberto de Veteri ponte, Willielmo Brigwerre, Ricardo de Munfichet, Petro filio Herberti, Matheo filio Herberti, Willielmo de Albiniaco, Roberto Gresley, Reginaldo de Brahus, Johanne de Munemutha, Johanne filio Alani, Hugone de Mortuomari, Waltero de Bellocampo, Willielmo de sancto Johanne, Petro de Malalacu, Briano de Insula, Thoma de Muletonia, Ricardo de Argentein., Gaulfrido de Nevilla, Willielmo Mauduit, Johanne de Baalun.

Datum apud Westmonasterium undecimo die februarii anno regni nostri nono.

THE THIRD GREAT CHARTER OF KING HENRY THE THIRD; *

Granted ad 1224–25,

In the Ninth Year of His Reign. Translated from the Original, Preserved in the Archives of Durham Cathedral.

Henry, by the Grace Of God, King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and Count of Anjou, to the Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots, Priors, Earls, Barons, Sheriffs, Governors, Officers, and all Bailiffs, and his faithful subjects, who see this present Charter,—Greeting. Know ye, that in the presence of God, and for the salvation of our own soul, and of the souls of our ancestors, and of our successors, to the exaltation of the Holy Church, and the amendment of our kingdom, that we spontaneously and of our own free will, do give and grant to the Archbishops, the Bishops, Abbots, Priors, Earls, Barons, and all of our kingdom, —these under-written liberties to be held in our realm of England for ever.—(I.) In the first place we grant unto God, and by this our present Charter we have confirmed for us, and for our heirs for ever, that the English Church shall be free, and shall have her whole rights and her liberties inviolable. We have also granted to all the free-men of our kingdom, for us and for our heirs for ever, all the under-written liberties to be had and held by them and by their heirs, of us and of our heirs.—(II.) If any of our Earls or Barons, or others who hold of us in chief by Military Service, shall die, and at his death his heir shall be of full age, and shall owe a relief, he shall have his inheritance by the ancient relief; that is to say, the heir or heirs of an Earl, a whole Earl’s Barony for one hundred pounds: the heir or heirs of a Baron, a whole Barony, for one hundred pounds; the heir or heirs of a Knight, a whole Knight’s Fee, for one hundred shillings at the most: and he who owes less, shall give less, according to the ancient customs of fees.—(III.) But if the heir of any such be under age, his Lord shall not have the Wardship of him nor of his land, before he shall have received his homage, and afterward such heir shall be in ward; and when he shall come to age, that is to say, to twenty and one years, he shall have his inheritance without relief and without fine: yet so, that if he be made a Knight, whilst he is under age, his lands shall nevertheless remain in custody of his Lords, until the term aforesaid.—(IV.) The warden of the land of such heir who shall be under age, shall not take from the lands of the heir any but reasonable issues, and reasonable customs, and reasonable services, and that without destruction and waste of the men or goods. And if we commit the custody of any such lands to a Sheriff, or to any other person who is bound to us for the issues of them, and he shall make destruction or waste upon the ward-lands, we will recover damages from him, and the lands shall be committed to two lawful and discreet men of the same fee, who shall answer for the issues to us, or to him to whom we have assigned them: and if we shall give or sell to any one the custody of any such lands, and he shall make destruction or waste upon them, he shall lose the custody; and it shall be committed to two lawful and discreet men of the same fee, who shall answer to us in like manner as it is said before.—(V.) But the warden, as long as he hath the custody of the lands, shall keep up and maintain the houses, parks, warrens, ponds, mills, and other things belonging to them, out of their issues; and shall restore to the heir, when he comes of full age, his whole estate, provided with carriages and all other things at the least as such as he received it. All these things shall be observed in the custodies of vacant Archbishoprics, Bishoprics, Abbies, Priories, Churches, and Dignities, which appertain to us; excepting that these wardships are not to be sold.—(VI.) Heirs shall be married without disparagement.—(VII.) A widow, after the death of her husband, shall immediately, and without difficulty, have her freedom of marriage and her inheritance; nor shall she give any thing for her dower, or for her freedom of marriage, or for her inheritance, which her husband and she held at the day of his death; and she may remain in the principal messuage of her husband, for forty days after husband’s death, within which time her dower shall be assigned; unless it shall have been assigned before, or excepting his house shall be a Castle; and if she depart from the Castle, there shall be provided for her a complete house in which she may decently dwell, until her dower shall be assigned to her as aforesaid: and she shall have her reasonable Estover within a common term. And for her dower, shall be assigned to her the third part of all the lands of her husband, which were his during his life, except she were endowed with less at the church door.—No widow shall be distrained to marry herself, whilst she is willing to live without a husband; but yet she shall give security that she will not marry herself, without our consent, if she hold of us, or without the consent of her lord if she hold of another.—(VIII.) We nor our Bailiffs, will not seize any land or rent for any debt, whilst the chattels of the debtor present sufficient for the payment of the debt, and the debtor shall be ready to make satisfaction: nor shall the sureties of the debtor be distrained, whilst the principal debtor is able to pay the debt; and if the principal debtor fail in payment of the debt, not having wherewith to discharge it, or will not discharge it when he is able, then the sureties shall answer for the debt; and if they be willing, they shall have the lands and rents of the debtor, until satisfaction be made to them for the debt which they had before paid for him, unless the principal debtor can shew himself acquitted thereof against the said sureties.—(IX.) The City of London shall have all its ancient liberties, and its free customs, as well by land as by water.—Furthermore, we will and grant that all other Cities, and Burghs, and Towns, and the Barons of the Cinque Ports, and all Ports, should have all their liberties and free customs.—(X.) None shall be distrained to do more service for a Knight’s-Fee, nor for any other free tenement, than what is due from thence.—(XI.) Common Pleas shall not follow our court, but shall be held in any certain place.—(XII.) Trials upon the Writs of Novel Disseisin and of Mort d’Ancestre, shall not be taken but in their proper counties, and in this manner:—We, or our Chief Justiciary, if we should be out of the kingdom, will send Justiciaries into every county, once in the year; who, with the knights of each county, shall hold in the county, the aforesaid assizes.—And those things, which at the coming of the aforesaid Justiciaries being sent to take the said assizes, cannot be determined, shall be ended by them in some other place in their circuit; and those things which for difficulty of some of the articles cannot be determined by them, shall be determined by our Justiciaries of the Bench, and there shall be ended.—(XIII.) Assizes of Last Presentation shall always be taken before our Justiciaries of the Bench, and there shall be determined.—(XIV.) A Free-man shall not be amerced for a small offence, but only according to the degree of the offence; and for a great delinquency, according to the magnitude of the delinquency, saving his contentment: and a Merchant in the same manner, saving his merchandise, and a villain, if he belong to another, shall be amerced after the same manner, saving to him his Wainage, if he shall fall into our mercy; and none of the aforesaid amerciaments shall be assessed, but by the oath of honest and lawful men of the vicinage.—Earls and Barons shall not be amerced but by their Peers, and that only according to the degree of their delinquency.—No Ecclesiastical person shall be amerced according to the quantity of his ecclesiastical benefice, but according to the quantity of his lay-fee, and the extent of his crime.—(XV.) Neither a town nor any person shall be distrained to build bridges or embankments, excepting those which anciently, and of right, are bound to do it.—(XVI.) No embankments shall from henceforth be defended, but such as were in defence in the time of King Henry our grandfather; by the same places, and the same bounds as they were accustomed to be in his time.—(XVII.) No Sheriff, Constable, Coroners, nor other of our Bailiffs, shall hold pleas of our crown.—(XVIII.) If any one holding of us a lay-fee die, and the Sheriff or our Bailiff shall shew our letters-patent of summons concerning the debt, which the defunct owed to us, it shall be lawful for the Sheriff, or for our Bailiff to attach and register all the goods and chattels of the defunct found on that lay-fee, to the amount of that debt by the view of lawful men. So that nothing shall be removed from thence until our debt be paid to us; and the rest shall be left to the executors to fulfil the will of the defunct; and if nothing be owing to us by him, all the chattels shall fall to the defunct, saving to his wife and children their reasonable shares.—(XIX.) No Constable, nor his Bailiff, shall take the corn or other goods of any one, who is not of that town where his Castle is, without instantly paying money for them, unless he can obtain a respite from the free will of the seller; but if he be of that town wherein the Castle is, he shall give him the price within forty days.—(XX.) No Constable shall distrain any Knight to give him money for Castle-guard, if he be willing to perform it in his own person, or by another able man, if he cannot perform it himself, for a reasonable cause: and if we do lead or send him into the army, he shall be excused from Castle-guard, according to the time that he shall be with us in the army, on account of the fee for which he hath done service in the host.—(XXI.) No Sheriff nor Bailiff of ours, nor of any other person, shall take the horses or carts of any, for the purpose of carriage, without paying according to the rate anciently appointed; that is to say, for a cart with two horses, ten-pence by the day, and for a cart with three horses, fourteen-pence by the day.—No demesne cart of any ecclesiastical person, or knight, or of any lord, shall be taken by the aforesaid Bailiffs.—Neither we, nor our Bailiffs, nor those of another, shall take another man’s wood, for our Castles or for other uses, unless by the consent of him to whom the wood belongs.—(XXII.) We will not retain the lands of those who have been convicted of felony, excepting for one year and one day, and then they shall be given up to the Lords of the fees.—(XXIII.) All Kydells (weirs) for the future, shall be quite removed out of the Thames and the Medway, and through all England, excepting upon the sea coast.—(XXIV.) The Writ which is called Præcipe, for the future shall not be granted to any one of any tenement, by which a Free-man loses his court.—(XXV.) There shall be one Measure of Wine throughout all our kingdom, and one Measure of Ale, and one Measure of Corn, namely, the Quarter of London; and one breadth of Dyed Cloth, of Russets, and of Halberjects, namely, Two Ells within the lists. Also it shall be the same with Weights as with Measures.—(XXVI.) Nothing shall for the future be given or taken for a Writ of Inquisition, nor taken of him that prayeth Inquisition of life or limb; but it shall be given without charge, and not denied.—(XXVII.) If any hold of us by Fee-Farm, or Socage, or Burgage, and hold land of another by Military Service, we will not have the custody of the heir, nor of his lands, which are of the fee of another, on account of that Fee-Farm, or Socage, or Burgage; nor will we have the custody of the Fee-Farm, Socage, or Burgage, unless the Fee-Farm owe Military Service. We will not have the custody of the heir, nor of the lands of any one, which he holds of another by Military Service, on account of any Petty-Sergeantry which he holds of us, by the service of giving us daggers, or arrows, or the like.—(XXVIII.) No Bailiff, for the future, shall put any man to his open law, nor to an oath, upon his own simple affirmation, without faithful witnesses produced for that purpose.—(XXIX.) No Free-man shall be taken, or imprisoned, or dispossessed, of his free tenement, or liberties, or free customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or in anyway destroyed; nor will we condemn him, nor will we commit him to prison, excepting by the legal judgment of his peers, or by the laws of the land.—To none will we sell, to none will we deny, to none will we delay right or justice.—(XXX.) All Merchants, unless they have before been publicly prohibited, shall have safety and security in going out of England, and in coming into England, and in staying and in travelling through England, as well by land as by water, to buy and sell, without any unjust exactions, according to ancient and right customs, excepting in the time of war, and if they be of a country at war against us: and if such are found in our land at the beginning of a war, they shall be apprehended, without injury of their bodies or goods, until it be known to us, or to our Chief Justiciary, how the Merchants of our country are treated who are found in the country at war against us: and if ours be in safety there, the others shall be in safety in our land.—(XXXI.) If any hold of any Escheat, as of the Honour of Wallingford, Boulogne, Nottingham, Lancaster, or of other Escheats which are in our hand, and are Baronies, and shall die, his heir shall not give any other relief, nor do any other service to us, than he should have done to the Baron, if those lands had been in the hands of the Baron; and we will bold it in the same manner that the Baron held it. Neither will we have, by occasion of any Barony or Escheat, any Escheat, or the custody of any of our men, unless he who held the Barony or Escheat, held otherwise of us in chief.—(XXXII.) No Free-man shall, from henceforth, give or sell any more of his land, but so that of the residue of his lands, the Lord of the fee may have the service due to him which belongeth to the fee.—(XXXIII.) All Patrons of Abbies, which are held by Charters of Advowson from the Kings of England, or by ancient tenure or possession of the same, shall have the custody of them when they become vacant, as they ought to have, and such as it hath been declared above.—(XXXIV.) No man shall be apprehended or imprisoned on the appeal of a woman, for the death of any other man than her husband.—(XXXV.) No County Court shall, from henceforth, be holden but from month to month; and where a greater term hath been used, it shall be greater. Neither shall any Sheriff or his Bailiff, keep his turn in the hundred but twice in the year; and no where but in due and accustomed place; that is to say, once after Easter, and again after the Feast of Saint Michael. And the view of Frank-pledge, shall be likewise at Saint Michael’s term, without occasion; so that every man may have his liberties, which he had and was accustomed to have, in the time of King Henry our grandfather, or which he hath since procured him. Also the view of Frank-pledge shall be so done, that our peace may be kept, and that the tything may be wholly kept, as it hath been accustomed; and that the Sheriff seek no occasions, and that he be content with so much as the Sheriff was wont to have for his view-making, in the time of King Henry our grandfather.—(XXXVI.) It shall not from henceforth, be lawful for any to give his lands to any Religious House, and to take the same land again to hold of the same House. Nor shall it be lawful to any House of Religion to take the lands of any, and to lease the same to him from whom they were received. Therefore, if any from henceforth do give his land to any Religious House, and thereupon be convict, his gift shall be utterly void, and the land shall accrue to the Lord of the fee.—(XXXVII.) Scutage from henceforth shall be taken as it was accustomed to be taken in the time of King Henry our grandfather.—Saving to the Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots, Priors, Templars, Hospitallers, Earls, Barons, and all others, as well ecclesiastical as secular persons, the liberties and free customs which they have formerly had.—Also all those customs and liberties aforesaid, which we have granted to be held in our kingdom, for so much of it as belongs to us, all our subjects, as well clergy as laity, shall observe towards their tenants as far as concerns them. And for this our grant and gift of these Liberties, and of the others contained in our Charter of Liberties of our Forest, the Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots, Priors, Earls, Barons, Knights, Free Tenants, and all others of our Kingdom, have given unto us the fifteenth part of all their move-ables. And we have granted to them for us and our heirs, that neither we nor our heirs shall procure or do any thing, whereby the Liberties in this Charter contained shall be infringed or broken; and if any thing shall be procured by any person contrary to the premises, it shall be had of no force nor effect. These being witnesses, the Lord Stephen Archbishop of Canterbury, Roger of London, Joceline of Bath, Peter of Winchester, Hugh of Lincoln, Richard of Salisbury, Benedict of Rochester, William of Worcester, John of Ely, Hugh of Hereford, Ralph of Chi-chester, William of Exeter, for the Bishops: the Abbot of Saint Edmund’s, the Abbot of Saint Alban’s, the Abbot of Battle Abbey, the Abbot of Saint Augustine’s Canterbury, the Abbot of Evesham, the Abbot of Westminster, the Abbot of Peterborough, the Abbot of Reading, the Abbot of Abingdon, the Abbot of Malmsbury, the Abbot of Winchcomb, the Abbot of Hyde, the Abbot of Chertsey, the Abbot of Sherburn, the Abbot of Cerne, the Abbot of Abbotsbury, the Abbot of Middleton, the Abbot of Selby, the Abbot of Whitby, the Abbot of Cirencester, Hubert de Burgh, the King’s Justiciary, Randolph Earl of Chester and Lincoln, William Earl of Salisbury, William Earl of Warren, Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester and Hertford, William de Ferrers, Earl of Derby, William de Mandeville, Earl of Essex, Hugh le Bigod, Earl of Norfolk, William Earl of Albemarle, Humphrey Earl of Hereford, John Constable of Chester, Robert de Ros, Robert Fitz Walter, Robert de Vipont, William de Brewer, Richard de Montfichet, Peter Fitz Herbert, Matthew Fitz Herbert, William de Albiniac, Robert Gresley, Reginald de Bruce, John de Monmouth, John Fitz Alan, Hugh de Mortimer, Walter de Beauchamp, William de Saint John, Peter de Mauley, Brian de Lisle, Thomas de Muleton, Richard de Argentine, Walter de Neville, William Mauduit, John de Baalun.—Given at Westminster, the Eleventh day of February, in the Ninth Year of our Reign.

[* ] The text given here is that of Statutes of the Realm (London: Record Commission, 1810–1828), 1:22–25, as reprinted in Faith Thompson, Magna Carta: Its Role in the Making of the English Constitution, 1300–1629 (Minneapolis, 1948), 377–82. Italicized words indicate those passages not found in the original 1215 Magna Carta of King John which were introduced in 1216, 1217, or 1225; numbers in parentheses refer to articles in the 1215 document.

[* ] Source: Richard Thomson, An Historical Essay on the Magna Charta of King John: To which are added, the Great Charter in Latin and English; The Charters of Liberties and Confirmations, Granted by Henry III. and Edward I.; The Original Charter of the Forests; and Various Authentic Instruments Connected with Them; etc. (London, 1829), 131–44.

Library electronic resources outage May 29th and 30th

Between 9:00 PM EST on Saturday, May 29th and 9:00 PM EST on Sunday, May 30th users will not be able to access resources through the Law Library’s Catalog, the Law Library’s Database List, the Law Library’s Frequently Used Databases List, or the Law Library’s Research Guides. Users can still access databases that require an individual user account (ex. Westlaw, LexisNexis, and Bloomberg Law), or databases listed on the Main Library’s A-Z Database List.

- Georgetown Law Library

- Legal History

Magna Carta: History & Legacy

- Journal Articles

- Georgetown Law Library Annotated Magna Carta Imprints

Key to Icons

- Georgetown only

- On Bloomberg

- More Info (hover)

- Preeminent Treatise

Introduction

National Archives 1297 Magna Carta

Getting Started

In this 800th Anniversary year there are numerous websites devoted to celebrating Magna Carta that include useful introductory essays, translations, timelines, and other resources. One of the best is that of the British Library ; another excellent anniversary themed site is that of Magna Carta 800th . NARA's site about their permanent exhibit of a 1297 copy is also quite good.

While there are now many available books to choose from, the works of J.C. Holt remain an invaluable starting point. His 1965 750th anniversary essay The Making of Magna Carta provides an excellent short introduction to the historical context, people and events of 1215. The 1972 edited collection of excerpts from significant contemporaneous and later works discussing Magna Carta together with essays by leading 20th century historians titled Magna Carta and the Idea of Liberty provides a concise introduction to the issues and questions raised by the long history of Magna Carta's influence. Magna Carta and Medieval Government from 1985 became the late 20th century's leading treatise on the origins of Magna Carta; it was significantly revised and expanded in a 1992 2nd ed. titled simply Magna Carta that also includes 14 appendices of supplementary essays, transcriptions of original texts of Magna Carta and related documents, and a collated translation of the original text from the four surviving 1215 copies.

Special Collections Librarian

- Next: Books >>

- © Georgetown University Law Library. These guides may be used for educational purposes, as long as proper credit is given. These guides may not be sold. Any comments, suggestions, or requests to republish or adapt a guide should be submitted using the Research Guides Comments form . Proper credit includes the statement: Written by, or adapted from, Georgetown Law Library (current as of .....).

- Last Updated: Sep 23, 2022 4:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=210937

The Magna Carta

--Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1941 Inaugural address

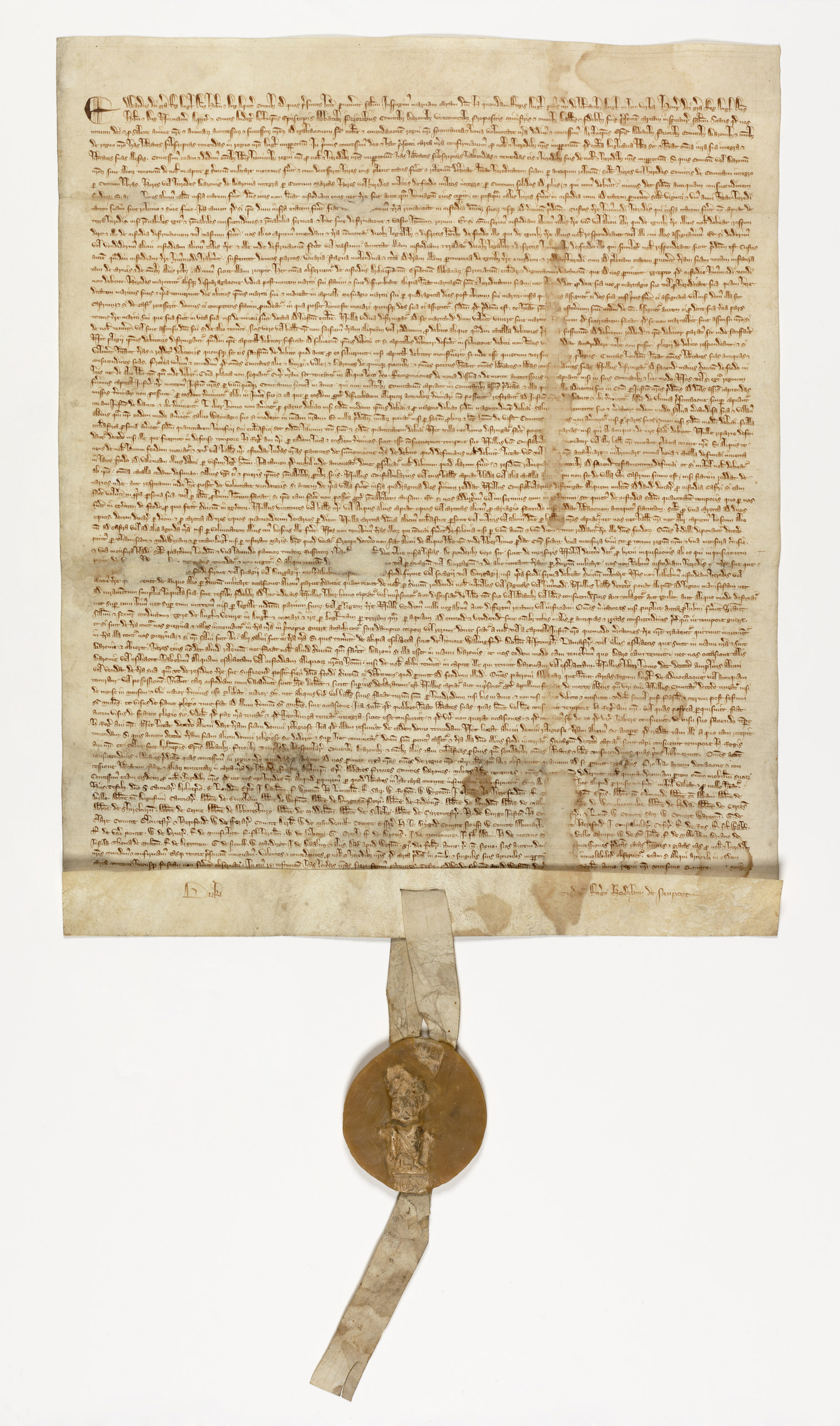

On June 15, 1215, in a field at Runnymede, King John affixed his seal to Magna Carta. Confronted by 40 rebellious barons, he consented to their demands in order to avert civil war. Just 10 weeks later, Pope Innocent III nullified the agreement, and England plunged into internal war.

Although Magna Carta failed to resolve the conflict between King John and his barons, it was reissued several times after his death. On display at the National Archives, courtesy of David M. Rubenstein, is one of four surviving originals of the 1297 Magna Carta. This version was entered into the official Statute Rolls of England.

Magna Carta was written by a group of 13th-century barons to protect their rights and property against a tyrannical king. It is concerned with many practical matters and specific grievances relevant to the feudal system under which they lived. The interests of the common man were hardly apparent in the minds of the men who brokered the agreement. But there are two principles expressed in Magna Carta that resonate to this day:

"No freeman shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or in any way destroyed, nor will We proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land."

"To no one will We sell, to no one will We deny or delay, right or justice."

Inspiration for Americans

During the American Revolution, Magna Carta served to inspire and justify action in libertys defense. The colonists believed they were entitled to the same rights as Englishmen, rights guaranteed in Magna Carta. They embedded those rights into the laws of their states and later into the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution ("no person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.") is a direct descendent of Magna Carta's guarantee of proceedings according to the "law of the land."

Select Magna Carta Resources

- You can view a short video about the Magna Carta conservation treatment and the Magna Carta encasement .

- You can read a translation of the 1297 version of Magna Carta, which was issued as part of Edward I's Confirmation of the Charters.

- "Magna Carta and Its American Legacy" provides a more in-depth look at the history of Magna Carta and the influence it had on American constitutionalism.

- You can also view a larger image of the Magna Carta.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Magna Carta, charter of English liberties granted by King John on June 15, 1215, under threat of civil war. By declaring the sovereign to be subject to the rule of law and documenting the liberties held by ‘free men,’ the Magna Carta provided the foundation for individual rights in Anglo-American jurisprudence.

The Magna Carta is widely considered to be one of the most important documents of all time, and is seen as being fundamental to how law and justice is viewed in countries all over the world. Prior to the Magna Carta being created there was no standing limit on royal authority in England.

The Magna Carta (or Great Charter) was written in Latin and was effectively the first written constitution in European history. It established the principle of respecting the law, limiting ...

List of some of the major causes and effects of the influential charter of liberties known as the Magna Carta. The charter was drawn up in England by barons and church leaders to limit the king’s power. They forced King John to sign the document in 1215.

The Magna Carta was designed as a peace agreement between King John and the barons. It failed to achieve this, and the two sides were at war with each other within three months of it being...

Magna Carta Libertatum (Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called Magna Carta or sometimes Magna Charta ("Great Charter"), [a] is a royal charter [4] [5] of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215.

The Magna Carta is the most famous document in British history, being introduced and signed by King John in 1215. The Magna Carta opened the doors to democracy in England and America. The Magna Carta or the “Great Charter” has been hailed as the “sacred text” of liberty in the Western World.

Magna Carta: A Commentary (1914) Subject Area: Law. Source: The Roots of Liberty: Magna Carta, Ancient Constitution, and the Anglo-American Tradition of Rule of Law, edited and with an Introduction by Ellis Sandoz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2008). Appendix: Text and Translation of Magna Carta.

His 1965 750th anniversary essay The Making of Magna Carta provides an excellent short introduction to the historical context, people and events of 1215.

Magna Carta was written by a group of 13th-century barons to protect their rights and property against a tyrannical king. It is concerned with many practical matters and specific grievances relevant to the feudal system under which they lived.