Write, learn, make friends, meet beta readers, and become the best writer you can be!

Join our writing group!

Poetic Devices List: 27 Main Poetic Devices with Examples

by Fija Callaghan

Fija Callaghan is an author, poet, and writing workshop leader. She has been recognized by a number of awards, including being shortlisting for the H. G. Wells Short Story Prize. She is the author of the short story collection Frail Little Embers , and her writing can be read in places like Seaside Gothic , Gingerbread House , and Howl: New Irish Writing . She is also a developmental editor with Fictive Pursuits. You can read more about her at fijacallaghan.com .

Emerging poets tend to fall into one of two camps.

The first are those who seek to embrace any and all poetic devices they can find and pile them one on top of the other, creating an architectural marvel not entirely dissimilar to a literary jenga puzzle—also known as Art.

The second are those who sit down at a desk/café table/riverside and throw up a beautiful storm of emotions onto the page, creating something so full of shadow and light and color that it could easily be mistaken for a post-impressionist painting or the remnants of a small child’s lunch. This, they assure us, is also Art.

The truth is, most poetry will fall somewhere in the middle. Many poets will begin learning about the technical literary devices used in poetry, read other poets who have used poetic devices successfully, and practice them in their own work until they become a part of their poet’s voice. Then they’ll allow them to surface naturally as they put their emotions down onto the page.

If you read any poetry at all (and if you haven’t, stop reading this, go do that, and come back), you’re probably well on your way. Many of the things we’re going to show you in this list of poetic devices are things you’ll probably recognize from other poems and stories you’ve read in the past.

What are poetic devices?

Poetic devices are techniques and methods writers use to construct effective poems. These poetic devices work on the levels of line-by-line syntax and rhythm, which make your poetry engaging and memorable; and they work on the deeper, thematic level, which makes your poetry matter to the reader.

Poetic devices are the literary techniques that give your poetry shape, brightness, and contrast.

Some of these poetic literary devices you probably already use instinctively. All poetry comes from a place within ourselves that recognizes the power of story and song, and writers have formed these devices in poetry over time as a way for us to communicate that with each other.

While you’re reading about these elements of poetry, see if you can look back at your own work and find where these poetic devices are already beginning to shine through naturally. Then you’ll be able to refine them even more to make your poetry the best it can be.

27 poetic devices used in poetry

Here are some of the literary devices you’ll be able to add to your poet’s toolkit:

1. Alliteration

Hearkening back to the days when poetry was mostly sung or read out loud, this literary device uses repeating opening sounds at the start of a series of successive words, giving them a lovely musical quality. The “Wicked Witch of the West” is an example of alliteration. So are “political power play” and “false friends.”

“Cold cider” is not an example of alliteration, because even though the words begin with the same letter, they don’t have the same sound. A ”sinking circus,” on the other hand, kicks off each word with the same sound even though they look different on the page.

2. Allusion

Allusion is where the poet makes an indirect reference to something outside of the poem, whether that’s a real person, a well-known mythological cycle, or a struggle that’s happening in the world we know. Sometimes this is simply to draw a parallel that the reader will easily understand, but often allusions are used to hint at something that it would be insensitive, or even dangerous, to directly acknowledge.

In Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven , the bird in question is described as “perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door.” Some of the poem’s readers may recognize Pallas as a reference to Pallas Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom. This allusion shows that the narrator has a high respect for learning.

3. Anaphora

Anaphora is the act of beginning a series of successive sentences or clauses (sentence fragments) with the same phrase. It’s an older literary device that many writers instinctively still use today, knowing that it lends a unique emphasis and rhythm even if they don’t know the specific term for it. You may have even used it yourself without realizing it!

One of the most famous uses of anaphora in English literature comes from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities : “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness.”

It goes on like this for a while, and the audience falls into not only a comfortable rhythm but a sense of audience participation; they begin to anticipate the words as they come, giving them a feeling of singing along to a song they’ve never heard. The repetition at the beginning of each line also draws attention to the contrasting ideas that Dickens is introducing.

This can be particularly effective in a narrative poem, or a poetic form that acts like a short story.

4. Assonance

Also called “vowel rhyme,” assonance is a poetic device that repeats vowel sounds in a word or phrase to create rhythm ( we’ll talk about rhythm a little more later on ). “Go slow down that lonely road” is an example of well-balanced assonance: we hear similar sounds in the “oh,” “go,” and “slow,” and then later in “lonely” and “road” (there’s also a bit of a clever eye rhyme in “slow down”—you’ll learn about eye rhymes when we talk about rhyme down below ). Don’t the deep, repetitive vowels just make you want to snuggle down into them?

You’ll probably find yourself using repeating vowel sounds in your poetry already, because the words just seem to naturally settle in together. As you progress, you’ll be able to see where those balanced vowels are beginning to shine through and then emphasize them even more.

5. Blank Verse

Blank verse is poetry that’s written in a regular meter, but with unrhymed line. It falls somewhere between formal and free verse poetry. While blank verse never has a formal rhyme scheme, it does have a formal meter (you’ll read more about meter a bit further on ).

Most blank verse is written in iambic pentameter, which was popularized by Shakespeare in his plays. “But soft! What light through yonder window breaks?” is a famous example—it doesn’t rhyme, but it follows a pattern of a ten syllable line with alternating unstressed and stressed syllables. Try reading it out loud.

Some blank verse uses internal rhyme, or words that rhyme within a line rather than at the end. Blank verse is a great way to add a poetic levity to writing that would otherwise read like prose.

6. Chiasmus

A chiasmus (a word that brings to mind the word “chimera”, coincidentally enough) is a stylized literary device that plays with the reversal of words or ideas.

Sometimes the words might be used together in a different way—“Never let a Fool Kiss You, or a Kiss Fool You”—or sometimes it may be the concepts of the idea that are presented in reflection—“My heart burned with anguish, and chilled was my body when I heard of his death”—with “heart” and “body” as parallels bookending the contrasting ideas of “burned” and “chilled.”

Like anaphora , chiasmus can draw attention to a contrasting idea and make a memorable impression on the reader.

7. Consonance

Compared to assonance , consonance is the repetition of consonant sounds in a word or phrase. Repeated consonants can occur at the beginning, middle, or ending of a word. You may recognize this from classic children’s tongue twisters like “Betty Botter bought some butter but she said the butter’s bitter”… the repeated B’s and T’s add a jig-and-reel quality to the speech.

You can also use this technique to add musicality and tone to the names of characters, such as the soft consonant sounds of Holly Golightly’s gentle L’s or the Dread Pirate Roberts’ guttural R’s.

In poetry, repeating consonant sounds often cause the reader to stop and linger over the phrase a little longer, teasing out both its music and its meaning (notice the consonance in “linger, little, longer” and “music” and “meaning”?).

8. Enjambment

Enjambment, from a Middle French word meaning “to step over,” is a poetic device in which a thought or an idea in a poem carries over from one line to another without pause. For example, T. S, Eliot’s The Waste Land says, “April is the cruelest month, breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing / Memory and desire.”

Instead of ending his lines on the comma, where we would normally think to pause in our speech, he includes the verb in the line before moving into the next one. This gives the poem a very different rhythm and complexity than it otherwise would have had.

Enjambment can also be used to create tension and surprise as the story you’re telling through your poem twists and turns.

9. Epistrophe

Unlike to anaphora , epistrophe is a literary device in which successive sentences or sentence fragments end with the same phrase. Our ears naturally attune to the landing point of any given word grouping, and so writers and speakers can use this tool to draw particular attention to a word or idea.

One famous example is Abraham Lincoln’s speech, “A government of the people, by the people, for the people”. We hear this word grouping “the people” landing three consecutive times. This same technique can be used to instill a mood in your poem by landing on evocative words such as “dark,” “gone,” or “again.”

10. Imagery

Imagery one of the most important poetic devices—it’s how you make the big ideas in your poem, as well as the poem’s meaning, come alive for the reader.

Poets will make the most of their limited space by using strong visual, auditory, olfactory, and even tactile sensations to give the reader a sense of time and place. It’s popular in both poetry and prose fiction.

In T. S. Eliot’s Preludes , he says, “… the burnt-out ends of smoky days. And now a gusty shower wraps the grimy scraps of withered leaves about your feet.” This little excerpt is brimming with an intense vision of the scene that plays with all five of the senses. It makes us feel like we’re there.

11. Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is contrast—comparing dark with light, heroes with villains, night with day, beauty with cruelty. “All’s fair in love and war” is a famous example of juxtaposition—the idea puts two normally conflicting concepts side by side to make us reconsider the relationship they have to each other.

Juxtaposition as a literary device can be lighthearted, such as a friendship between a lion and a mouse, or it can give power and emotional resonance to a scene, such as young soldiers leaving for grim battle on a perfectly beautiful summer’s day. Effective use of juxtaposition can change the tone of an entire poem.

12. Metaphor

Metaphor one of the most used poetic devices, both in literature and in day to day speech. It presents one thing as another completely different thing so as to draw a powerful comparison of images.

“Love is a battlefield” is a metaphor that equates a broad, thematic idea (love) with something we all have at least a basic understanding of (a battlefield). It shows us that there are aspects in each that are also present in the other.

Metaphors can also be implied, when the poet uses a colorful image to suggest something about a character or an action; for instance, “the article sparked a new conversation,” giving the article a quality akin to a flame struck in the darkness.

Rather than stating its literal meaning, a metaphor makes the meaning of the entire poem even stronger.

Meter is the way in which rhythm is measured in a poem. It’s a pattern that functions on two basic premises: the number of syllables in a line of poetry, and how each syllable is either stressed (given emphasis, such as the first syllable of “nature”) or unstressed.

We express the type of meter the poem follows also in two parts: the structure of stressed and unstressed syllables, and how many of them there are in a single line.

There are many kinds of formal meter. Perhaps the most famous one is iambic pentameter, made famous by the sonnets Shakespeare wrote—a fourteen line poem in which the iamb (one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable, like “toNIGHT,” “beLONG,” “beCOME”) is repeated five times in a line.

But there can be many other kinds of meter, depending on how many metrical feet (like an iamb) appear per line. For example, iambic tetrameter uses the same structure as iambic pentameter but with only eight syllables instead of ten.

14. Metonym

Similar to a metaphor , a metonym is a poetic device which uses an image or idea to stand in place of something.

This can be visual, such as in road signs or computer icons, where a downwards arrow stands in place of the concept for “download,” or it can be literary.

To say “the White House is in discussion” usually refers to a group of elected government officials, rather than an actual constructed house that has been painted white.

A “mother tongue” is a native language, and “the press” is often used as a broad metonym for journalists. Some metonyms are no longer in use, and can be worked into poems to show setting and context—for instance, “hot ice” to mean stolen diamonds.

A motif is a symbol or idea that appears repeatedly to help support what the poet is trying to communicate. In poetry, motifs are often things with which we already have a cultural relationship—bodies of water to represent purity, sunrises to represent new beginnings, storm clouds to represent dramatic change.

When these ideas are used once in your poem, they’re a poetic device called symbolism . To be a motif, they’d need to be used in repetition, with each interval creating stronger and stronger links between the themes of the poem and the reader’s understanding of the world.

Myths and legends are perhaps the greatest reservoir of creativity the poet has at their disposal. Though often used interchangeably, myths are stories that tell of how something came to be—for example Noah’s ark, or the story behind the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland. Legends are stories that blur the lines of myth and history, for instance the Greek heroes in the saga of Troy.

It’s worth looking to the stories from your own region and cultural background for inspiration. Contrary to what some might say, there’s also nothing wrong with embracing the stories of other cultures so long as they are done with reverence and respect.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, an American poet of European descent, wrote beautifully about Native American myths in his Song of Hiawatha .

17. Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia are great poetic devices for adding rhythm and sensory presence to your work. Onomatopoeia are words that, when spoken out loud, imitate sounds like what they’re intended to mean.

“Buzzing,” for instance, is a verb that relates to the action of a traveling bee, but spoken aloud it sounds like the actual sound bees make. “Murmuring,” “humming,” and “smacking” all sound like the actions that they refer to. In poetry, you can have a lot of fun experimenting with onomatopoeia to make your reader feel like they’re in the poem alongside you.

18. Personification

Personification is a poetic device that gives a non-human entity—whether that’s an animal, a plant, or a cantankerous dancing candlestick—human characteristics, actions, and feelings. Sometimes this might be so extreme as to create an entirely human character with a nonhuman shape. Many, many Disney movies follow this pattern.

In poetry, very often the personification is more subtle; “the waves stretching their white fingers up towards the sun,” or “shadows leering down accusingly” are both examples of more subtle personification. These fanciful images come from the narrator’s relationship to the moment in time and their environment.

19. Repetition

Repetition is used both as a poetic device and as an aspect of story structure, particularly when dealing in motifs . In poetry, using the same word or phrase repeatedly allows the reader or listener to settle into a comfortable rhythm, offering them a sense of familiarity even if they’ve never heard that particular piece before.

It can also be used to bring seemingly unrelated lines and stanzas back to the same idea. You can write poems with repeating words or phrases, or you can repeat broader ideas that you come back to again and again as the poem progresses.

When most people think of rhyming words they tend to think of what’s called a “perfect rhyme,” in which the final consonants, final vowels, and the number of syllables in an ending word match completely. These are rhymes like “table” and “fable”, or “sound” and “ground.”

But there are many different kinds of rhymes. Other types include slant rhymes (in which some of the consonants or the vowels match, but not all—for example, “black” and “blank”), internal rhymes (perfect rhymes that are used for rhythmic effect inside a line of poetry, for instance “double, double, toil and trouble)”, and eye rhymes (words that look like they should rhyme only when read and not heard aloud, like “date” and “temperate,” or “love” and “move”).

The rhyme scheme, or pattern of rhyming lines, a poem uses can have a big impact on the poem’s mood and language.

The true purpose of a rhyme scheme is to give your poetry rhythm , which is the shape and pattern a poem takes. What it comes down to is getting your words inside the reader’s bones. Rhyme is one way to do this, and meter is another. So are line-level poetic devices like assonance , consonance , and alliteration .

The length of your lines and your style of language will also play a part; quick, short words in quick, short lines of poetry give the poem a snappy feel, while longer, more indulgent lines will slow down the rhythm. The rhythm of the poem should match the story that it’s telling.

It’s a good idea to experiment with different kinds of rhythm in your poetry, though many poets develop a comfortable rhythmic place in which their poetry feels most at home.

Similes often get lumped together with metaphors as poetic devices that express the similarities between two seemingly unrelated ideas. They serve a very similar purpose in poetry, but are approached slightly differently. Where a metaphor uses one idea to stand in place for another, a simile simply draws a comparison between these two things.

Examples of similes are Shakespeare’s “Her hair, like golden threads, play’d with her breath” and Langston Hughes’ “What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?” The word “like” in these examples is the hint that we’re looking at a simile, and not a metaphor.

Using similes is a great way to impart sensory imagery and to get your readers to think about something in a new way.

23. Symbolism

We looked at motifs earlier as recurring symbols in a poem. Not all symbolism is recurring, but all of it should support what the poet is trying to say as a larger whole.

Symbols in poetry might be sensory images, they might be metaphors for a real life issue, or they might be cultural icons with which we already have deeply-ingrained associations.

Examples could be a skull to represent death, a dove to represent peace, or the sun and the moon to represent masculine and feminine polarities. By tapping into this pre-existing cultural consciousness, the poet has an entirely new language with which to communicate.

24. Synecdoche

Synecdoche is similar to a metonym , in that it takes a small part of something to represent something bigger. But rather than looking at something symbolically representative of a whole, synecdoche is a poetic device that looks at a physical part of that whole. To say “give me a hand”, for instance, means “give me assistance” (which may or may not involve an actual hand), or “all hands on deck” to mean “all bodies, hands and feet included.”

It can sometimes be used in the opposite way too, using a larger picture to represent a smaller part. For example, to say “New York is up against Chicago” probably doesn’t refer to an actual civil war between two warring cities—most likely you’re just talking about a smaller part of a whole, like a sports team.

Tmesis, apart from being a word that kind of looks like a sneeze, is another dialectal poetic device. It comes from a Greek word meaning “to cut,” and involves cutting a word in half for emphasis. Sometimes this is colloquial, like “abso-bloody-lutely” or “fan-bloody-tastic” (really, any time an irate British person sticks “bloody” into a perfectly serviceable word).

It’s also used in poetry and poetic prose to add emphasis to the idea. In Romeo and Juliet , Romeo says, “This is not Romeo, he’s some other where”, interjecting “other” into “somewhere” for emphasis. Tmesis is a fun poetic device to play around with, that allows you to begin looking at words in a different way.

Tone is the not-entirely-quantifiable mood, or atmosphere, of your piece. Some poets are great at crafting dark, haunting poetry; others write poems full of soft sunshine that make you think of a languid summer morning in the grass.

You may find that different themes and messages require different moods, but very likely you’ll find yourself settling into one signature atmosphere as you develop your poet’s voice.

The best way to do this is to read poems of all different tones and styles to see which resonate best with you. You could also try making “mood banks” of words to play around with in your poetry, either as lists or as little bits of paper á la “magnetic poetry.”

Words like “night,” “silence,” and “howl” conjure up one idea; words like “sunday,” “popcorn,” and “sparrow” conjure up something very different.

A zeugma, as well as being your new secret weapon in Scrabble, is a poetic device that was used quite a lot in old Greek poetry but isn’t seen as much these days—largely because it’s difficult to do well. It’s when a poet uses a word in one sentence to mean two different things, often meaning a literal one, and one meaning a figurative one.

For example, “he lost his passport and his temper” or “I left my heart and my favorite scarf in Santa Fé” are two instances where the verb is used in both literal and figurative ways.

How to use poetic devices

Seeing the range of word-level tools available to you as a writer can be both exciting and a little overwhelming. As you can see, the twenty-six unassuming little letters of the English language carry within them a world of possibility—the poet just needs to know how to make them dance.

There are two ways to begin working with poetic devices, both of them essential: the first is to read. Read classic poetry, modern poetry, free verse, blank verse, poetry written by men and women of all walks of life. Look at ways other artists have used these poetic devices effectively, and see which moments in their work resonate with you the most. Then ask yourself why and what you can do to bring that light into your own poetry.

The second is to write. The poet and novelist Margaret Atwood famously said, “You become a writer by writing. There is no other way.” Reading poetry and reading about poetry is an important part of understanding technique, but the only real way to get these poetic devices in your bones and blood is to begin.

If you’ve started writing your own poetry already, go back and look at some of your earlier work. Can you spot any of the poetic devices from this list?

Many of these literary devices work because they resonate with our innate human instincts for rhythm and storytelling. You probably already use some of them without realizing it. See where you can pick out these little seeds and bring them to life even more.

As you progress, your awareness of technical literary devices in poetry such as assonance, epistrophe, metonymy, and poetic form will become as natural as a musician who no longer needs to look at the keys—they simply form a part of your poet’s voice.

Join one of the largest writing communities online!

Scribophile is a community where writers from all over the world grow their creative lives together. Write, learn, meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer with us!

Join now for free

Related articles

What is Rhythm in Literature? Definition and Examples

What is Alliteration? Definition, examples and tips

Short Story Submissions: How to Publish a Short Story or Poem

How to Write a Haiku (With Haiku Examples)

What Is Repetition in a Story: Definition and Examples of Repetition in Literature

What is Foreshadowing? Definition, Types, Examples, and Tips

Holiday Giving: Get 10% Off Gifted Writers.com Course Credit! Learn more »

What do the words “anaphora,” “enjambment,” “consonance,” and “euphony” have in common? They are all literary devices in poetry—and important poetic devices, at that. Your poetry will be greatly enriched by mastery over the items in this poetic devices list, including mastery over the sound devices in poetry.

This article is specific to the literary devices in poetry. Before you read this article, make sure you also read our list of common literary devices across both poetry and prose, which discusses metaphor, juxtaposition, and other essential figures of speech.

We will be analyzing and identifying poetic devices in this article, using the poetry of Margaret Atwood, Louise Glück, Shakespeare, and others. We also examine sound devices in poetry as distinct yet essential components of the craft.

Poetic Devices: Contents

- Metonymy & Synecdoche

- Enjambment & End-Stopped Lines

- Internal & End Rhyme

- Alliteration

- Consonance & Assonance

- Euphony & Cacophony

Literary Devices in Poetry: Poetic Devices List

Let’s examine the essential literary devices in poetry, with examples. Try to include these poetic devices in your next finished poems!

1. Anaphora

Anaphora describes a poem that repeats the same phrase at the beginning of each line. Sometimes the anaphora is a central element of the poem’s construction; other times, poets only use anaphora in one or two stanzas, not the whole piece.

Consider “ The Delight Song of Tsoai-talee ” by N. Scott Momaday.

I am a feather on the bright sky I am the blue horse that runs in the plain I am the fish that rolls, shining, in the water I am the shadow that follows a child I am the evening light, the lustre of meadows I am an eagle playing with the wind I am a cluster of bright beads I am the farthest star I am the cold of dawn I am the roaring of the rain I am the glitter on the crust of the snow I am the long track of the moon in a lake I am a flame of four colors I am a deer standing away in the dusk I am a field of sumac and the pomme blanche I am an angle of geese in the winter sky I am the hunger of a young wolf I am the whole dream of these things

You see, I am alive, I am alive I stand in good relation to the earth I stand in good relation to the gods I stand in good relation to all that is beautiful I stand in good relation to the daughter of Tsen-tainte You see, I am alive, I am alive

This poem is an experiment in metaphor: how many ways can the self be reproduced after “I am”? The simple “I am” anaphora draws attention towards the poet’s increasing need to define himself, while also setting the poet up for a series of well-crafted poetic devices.

Anaphora describes a poem that repeats the same phrase at the beginning of each line.

The self shapes the core of Momaday’s poem, as emphasized by the anaphora. Still, our eye isn’t drawn to the column of I am’s, but rather to Momaday’s stunning metaphors for selfhood.

A conceit is, essentially, an extended metaphor . Which, when you think about it, it’s kind of stuck-up to have a fancy word for an extended metaphor, so a conceit is pretty conceited, don’t you think?

In order for a metaphor to be a conceit, it must run through the entire poem and be the poem’s central device. Consider the poem “ The Flea ” by John Donne. The speaker uses the flea as a conceit for physical relations, arguing that two bodies have already intermingled if they’ve shared the odious bed bug. With the flea as a conceit for intimacy, Donne presents a poem both humorous and strangely erotic.

A conceit must run through the entire poem as the poem’s central device.

The conceit ranks among the most powerful literary devices in poetry. In your own poetry, you can employ a conceit by exploring one metaphor in depth. For example, if you were to use matchsticks as a metaphor for love, you could explore love in all its intensity: love as a stroke of luck against a matchbox strip, love as wildfire, love as different matchbox designs, love as phillumeny, etc.

3. Apostrophe

Don’t confuse this with the punctuation mark for possessive nouns—the literary device apostrophe is different. Apostrophe describes any instance when the speaker talks to a person or object that is absent from the poem. Poets employ apostrophe when they speak to the dead or to a long lost lover, but they also use apostrophe when writing an ode to something, such as Ode to a Grecian Urn or an Ode to the Women in Long Island .

Apostrophe is often employed in admiration or longing, as we often talk about things far away in wistfulness or praise. Still, try using apostrophe to express other emotions: express joy, grief, fear, anger, despair, jealousy, or ecstasy, as this poetic device can prove very powerful for poetry writers.

4. Metonymy & Synecdoche

Metonymy and synecdoche are very similar poetic devices, so we’ll include them as one item. A metonymy is when the writer replaces “a part for a part,” choosing one noun to describe a different noun. For example, in the phrase “the pen is mightier than the sword,” the pen is a metonymy for writing and the sword is a metonymy for fighting.

Metonymy: a part for a part.

In this sense, metonymy is very similar to symbolism , because the pen represents the idea of writing. The difference is, a pen is directly related to writing, whereas symbols are not always related to the concepts they represent. A dove might symbolize peace, but doves, in reality, have very little to do with peace.

Synecdoche is a form of metonymy, but instead of “a part for a part,” the writer substitutes “a part for a whole.” In other words, they represent an object with only a distinct part of the object. If I described your car as “a nice set of wheels,” then I’m using synecdoche to refer to your car. I’m also using synecdoche if I call your laptop an “overpriced sound system.”

Synecdoche: a part for a whole.

Since metonymy and synecdoche are forms of symbolism, they appear regularly in poetry both contemporary and classic. Take, for example, this passage from Shakespeare’s A Midsommar Night’s Dream :

Shakespeare makes it seem like the poet’s pen gives shape to airy wonderings, when in fact it’s the poet’s imagination. Thus, the pen becomes metonymous for the magic of poetry—quite a lofty comparison, which only a bard like Shakespeare could say.

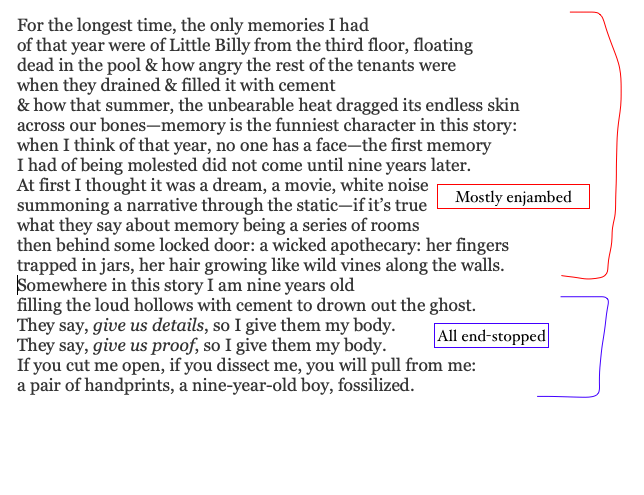

5. Enjambment & End-Stopped Lines

Poets have something at their disposal which prose writers don’t: the mighty line break. Line breaks and stanza breaks help guide the reader through the poem, and while these might not be hardline “literary devices in poetry,” they’re important to understanding the strategies of poetry writing.

Line breaks can be one of two things: enjambed or end-stopped. End-stopped lines are lines which end on a period or on a natural break in the sentence. Enjambment, by contrast, refers to a line break that interrupts the flow of a sentence: either the line usually doesn’t end with punctuation, and the thought continues on the next line.

Let’s see enjambed and end-stopped lines in action, using “ The Study ” by Hieu Minh Nguyen.

Most of the poem’s lines are enjambed, using very few end-stops, perhaps to mirror the endless weight of midsummer. Suddenly, the poem shifts to end-stops at the end, and the mood of the poem transitions: suddenly the poem is final, concrete in its horror, horrifying perhaps for its sincerity and surprising shift in tone.

Line breaks and stanza breaks help guide the reader through the poem.

Enjambment and end-stopping are ways of reflecting and refracting the poem’s mood. Spend time in your own poetry determining how the mood of your poems shift and transform, and consider using this poetry writing strategy to reflect that.

Zeugma (pronounced: zoyg-muh) is a fun little device you don’t see often in contemporary poetry—it was much more common in ancient Greek and Latin poetry, such as the poetry of Ovid. This might not be an “essential” device, but if you use it on your own poetry, you’ll stand out for your mastery of language and unique stylistic choices.

A zeugma occurs when one verb is used to mean two different things for two different objects. For example, I might say “He ate some pasta, and my heart out.” To eat pasta and eat someone’s heart out are two very different definitions for ate: one consumption is physical, the other is conceptual. The key here is to only use “ate” once in the sentence, as a zeugma should surprise the reader.

Now, take this excerpt from Ovid’s Heroides 7 :

Can you identify the zeugmas? “Bear” and “weigh” are both used literally and figuratively, bearing weight to the speaker’s laments.

Zeugmas are a largely classical device, because the constraints of ancient poetic meter were quite strict, and the economic nature of Latin encouraged the use of zeugma. Nonetheless, try using it in your own poetry—you might surprise yourself!

7. Repetition

Strategic repetition of certain phrases can reinforce the core of your poem.

Last but not least among the top literary devices in poetry, repetition is key. We’ve already seen repetition in some of the aforementioned poetic devices, like anaphora and conceit. Still, repetition deserves its own special mention.

Strategic repetition of certain phrases can reinforce the core of your poem. In fact, some poetry forms require repetition, such as the villanelle . In a villanelle, the first line must be repeated in lines 6, 12, and 18; the third line must be repeated in lines 9, 15, and 19.

See this repetition in action in Sylvia Plath’s “ Mad Girl’s Love Song. ” Notice how the two repeated lines reinforce the subjects of both love and madness—perhaps finding them indistinguishable? Take note of this masterful repetition, and see where you can strategically repeat lines in your own poetry, too.

Learn more about this poetic device here:

Repetition Definition: Types of Repetition in Poetry and Prose

Sound Devices in Poetry

The other half of this article analyzes the different sound devices in poetry. These poetic sound devices are primarily concerned with the musicality of language, and they are powerful poetic devices for altering the poem’s mood and emotion—often in subtle, surprising ways.

What are sound devices in poetry, and how do you use them? Let’s explore these other literary devices in poetry, with examples.

8. Internal & End Rhyme

When you think about poetry, the first thing you probably think of is “rhyme.” Yes, many poems rhyme, especially poetry in antiquity. However, contemporary poetry largely looks down upon poetry with strict rhyme schemes, and you’re far more likely to see internal rhyming than end rhyming.

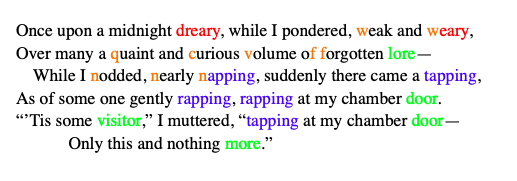

Internal rhyme is just what it sounds like: two rhyming words juxtaposed inside of the line, rather than at the end of the line. See internal rhyme in action Edgar Allan Poe’s famous “ The Raven ”:

Each of the rhymes have been assigned their own highlighted color. I’ve also highlighted examples of alliteration, which this article covers next.

Despite “The Raven’s” macabre, dreary undertones, the play with language in this poem is entertaining and, quite simply, fun. Not only does it draw readers into the poem, it makes the poem memorable—after all, poetry used to rhyme because rhyme schemes helped people remember the poetry, long before people had access to pen and paper.

Why does contemporary poetry frown at rhyme schemes? It’s not the rhyming itself that’s odious; rather, contemporary poetry is concerned with fresh, unique word choice , and rhyme schemes often limit the poet’s language, forcing them to use words which don’t quite fit.

contemporary poetry is concerned with fresh, unique word choice, and rhyme schemes often limit the poet’s language

If you can write a rhyming poem with precise, intelligent word choice, you’re an exception to the rule—and far more skilled at poetry than most. Perhaps you should have been born a bard in the 16th century, blessed with the king’s highest graces, splayed dramatically on a decadent chaise longue with maroon upholstery, dining on grapes and cheese.

9. Alliteration

Alliteration is a powerful, albeit subtle, means of controlling the poem’s mood.

One of the more defining sound devices in poetry, alliteration refers to the succession of words with similar sounds. For example: this sentence, so assiduously steeped in “s” sounds, was sculpted alliteratively. (This s-based alliteration is called sibilance!)

Alliteration is a powerful, albeit subtle, means of controlling the poem’s mood. A series of s’es might make the poem sound sinister, sneaky, or sharp; by contrast, a series of b’s, d’s, and p’s will give the poem a heavy, percussive sound, like sticks against a drum.

Emily Dickenson puts alliteration to play in her brief poem “ Much Madness .” The poem is a cacophonous mix of s, m, and a sounds, and in this cacophony, the reader gets a glimpse into the mad array of the poet’s brain.

Alliteration can be further dissected; in fact, we could spend this entire article talking about alliteration if we wanted to. What’s most important is this: playing with alliterative sounds is a crucial aspect of poetry writing, helping readers experience the mood of your poetry.

10. Consonance & Assonance

Along with alliteration, consonance and assonance share the title for most important sound devices in poetry. Alliteration refers specifically to the sounds at the beginning: consonance and assonance refer to the sounds within words. Technically, alliteration is a form of consonance or assonance, and both can coexist powerfully on the same line.

Consonance refers to consonant sounds, whereas assonance refers to vowel sounds. You are much more likely to read examples of consonance, as there are many more consonants in the English alphabet, and these consonants are more highly defined than vowel sounds. Though assonance is a tougher poetic sound device, it still shows up routinely in contemporary poetry.

In fact, we’ve already seen examples of assonance in our section on internal rhyme! Internal rhymes often require assonance for the words to sound similar. To refer back to “The Raven,” the first line has assonance with the words “dreary,” “weak,” and “weary.” Additionally, the third line has consonance with “nodded, nearly napping.”

These poetic sound devices point towards one of two sounds: euphony or cacophony.

11. Euphony & Cacophony

Poems that master musicality will sound either euphonious or cacophonous. Euphony, from the Greek for “pleasant sounding,” refers to words or sentences which flow pleasantly and sound sweetly. Look towards any of the poems we’ve mentioned or the examples we’ve given, and euphony sings to you like the muses.

Cacophony is a bit harder to find in literature, though certainly not impossible. Cacophony is euphony’s antonym, “unpleasant sounding,” though the effect doesn’t have to be unpleasant to the reader. Usually, cacophony occurs when the poet uses harsh, staccato sounds repeatedly. Ks, Qus, Ls, and hard Gs can all generate cacophony, like they do in this line from “ Rime of the Ancient Mariner ” from Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

Reading this line might not be “pleasant” in the conventional sense, but it does prime the reader to hear the speaker’s cacophonous call. Who else might sing in cacophony than the emotive, sea-worn sailor?

What’s something you still remember from high school English? Personally, I’ll always remember that Shakespeare wrote in iambic pentameter. I’ll also remember that iambic pentameter resembles a heartbeat: “love is a smoke made with the fumes of sighs .” ba- dum , ba- dum , ba- dum .

Metrical considerations are often reserved for classic poetry. When you hear someone talking about a poem using anapestic hexameter or trochaic tetrameter, they’re probably talking about Ovid and Petrarch, not Atwood and Glück.

Still, meter can affect how the reader moves and feels your poem, and some contemporary poets write in meter.

Before I offer any examples, let’s define meter. All syllables in the English language are either stressed or unstressed. We naturally emphasize certain syllables in English based on standards of pronunciation, so while we let words like “love,” “made,” and “the” dangle, we emphasize “smoke,” “fumes,” and “sighs.”

Depending on the context, some words can be stressed or unstressed, like “is.” Assembling words into metrical order can be tricky, but if the words flow without hesitation, you’ve conquered one of the trickiest sound devices in poetry.

Common metrical types include:

- Iamb: repetitions of unstressed-stressed syllables

- Anapest: repetitions of unstressed-unstressed-stressed syllables

- Trochee: repetitions of stressed-unstressed syllables

- Dactyl: repetitions of stressed-unstressed-unstressed syllables

Finding these prosodic considerations in contemporary poetry is challenging, but not impossible. Many poets in the earliest 20th century used meter, such as Edna St. Vincent Millay. Her poem, “ Renascence ,” built upon iambic tetrameter. Still, the contemporary landscape of poetry doesn’t have many poets using meter. Perhaps the next important metrical poet is you?

Mastering the Literary Devices in Poetry

Every element of this poetic devices list could take months to master, and each of the sound devices in poetry requires its own special class. Luckily, the instructors at Writers.com know just how to sculpt poetry from language, and they’re ready to teach you, too. Take a look at our upcoming poetry courses , and take the next step in mastering the literary devices in poetry.

Sean Glatch

43 comments.

Very interesting stuff! I’m looking forward to incorporating some of these devices in my future poetry.

Incredible. Somes are new btw.

Wow … learned alot with this…. thanks

Well illustrated, simple language and easily understood. Thank you.

While thinking of an appropriate inscription for my dad’s headstone, the following two thoughts came to mind:

“He served his country with honor and he honored his wife with love.”

Can the above be described as being an example of any particular kind of literary or poetic device?

The Real Person!

Hi Louis, good question! This is an example of polyptoton, a repetition device in which words from the same root are employed simultaneously. You can learn more about it at this article: writers.com/repetition-definition

You’re also close to using what’s called a syllepsis or zeugma. From the Greek for “a yoking,” a zeugma is when you use the same verb to mean two different things. An example: “He ate his feelings–and the cheesecake.” “Ate” is being used both figuratively and literally, “yoking” the two meanings together.

Your sentence uses honor as both a noun and a verb, which makes it a bit distinct from other zeugmas. Regardless, it’s a thoughtful sentiment and a lovely sentence. I hope this helps!

It’s called a polyptoton. Repetition, in close proximity, of different grammatical forms of the same root word. Honor/noun Honored/ verb It’s not zeugma when the word which would be yoked, is instead repeated. I discovered this literary device one day, some years into my teaching career, by reading the literary dictionary with my students. We were very happy to find the term, after several students had inquired about a passage we were analyzing, and I had no answer (except a form of repetition). The class cheered when I read it out. I can’t imagine that happening today…

Isn’t it alliteration… ‘h’ sound is repeated 🤔

It is an alliteration, zeugma, assonance, consonance

It is called a polyptoton — a literary device of repetition involving the use, in close proximity, of more than one grammatical form of the same word. In this case honor (noun) and honored (verb). Famous example: “The Greeks are strong and skilful in their strength, Fierce to their skill, and to their fierceness valiant.” Strong/strength & skilful/skill & fierce/fierceness = adjective/noun forms — in very close proximity (within a single sentence).

It’s a powerful dream of mine you just inspired me

These are very helpful! I am a poet, and I did not know about half of these! Thank you.

We’re so glad this article was helpful! Happy writing 🙂

I am definitely loving this article. I have learnt a lot.

Thank you so much for this article. it is quite refreshing and enlightening.

the article was helpful during my revisions

As apostrophe is used to make a noun possessive case, not plural. (#3)

You’re correct when it comes to the grammatical apostrophe, but as a literary device, apostrophe is specifically an address to someone or something that isn’t present in the work itself. For some odd reason, they share the same name. 🙂

You can learn more about the apostrophe literary device here . I hope this makes sense!

@Sean Glatch

I believe this comment was intended as a correction to the phrase ‘the punctuation mark for plural nouns’ used in the article. Plural nouns aren’t apostrophised, which makes that an error.

Very knowledgeable to learn, I want to learn more……

Very knowledgeable and detailed.

I think that a cool literary device to add would be irony. Its my favorite 🙂

Thanks, Patricia! We have an article on irony at this link .

Happy writing!

I am a student currently studying English Literature. Really appreciate the article and the effort put into it because its made some topics more clear to me. However, is there any place where I can find more examples of the devices Enjambement, metonymy, iambic pentameter, consonance & cacophony? Would appreciate it a bunch❤ Thank you again for the article

I’m so glad this article was helpful! We cover a few more topics in poetry writing at this article: https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

in my high school in uganda, we study about these devices that’s if you offer literature as a subject

Very helpful and relevant…

I just came here to check out some poetic devices so that I can pass through my exam…but looking at these comments made me feel like…where am I? Is this the land of the angels? Thanks for the motivation, probably not a poet but I am writing stories now, made a good one already.

Very precious knowledge . Thanks alot.

Thank you, You have taught me a lot .

Really needed this for my AP Lit class, thanks for making it so understandable!

This article was extremely informative. I love the platform. Wonderful to find other individuals passionate about language. I absolutely enjoyed the discourse.

I have learnt a lot, may God bless you forever. Thank you so much.

This was very informative to read, thank you. i do have one question. I have searched over the internet and I’m struggling to find my answer. Do you know if there’s a name for when a poem starts with a rhetorical question in the beginning line, and then answers it in the very last line. Take ‘Who’s For the Game?’ by Jessie Pope as an example. Thx

Fantastic thank you very helpful

ELA educator here; glad to have this well-written and concise information for my classroom! Thank you! Instagram @jenlee_123

Thank you very much, I have learned a lot. Hopefully I’ll do the best in my assignments.

Thank you. I polished my dusty knowledge of literature.

Thank you so much. I needed this for my AP LIT exam. Now I can write my essay – Ish Da Fish

I needed a quick review and this is perfect. Thank you.

Thank you I have learned so much

I really gained a lot here

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO