- Login / Sign Up

Fearless journalism needs your support now more than ever

Our mission could not be more clear and more necessary: We have a duty to explain what just happened, and why, and what it means for you. We need clear-eyed journalism that helps you understand what really matters. Reporting that brings clarity in increasingly chaotic times. Reporting that is driven by truth, not by what people in power want you to believe.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

The Stanford Prison Experiment was massively influential. We just learned it was a fraud.

The most famous psychological studies are often wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. Textbooks need to catch up.

by Brian Resnick

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

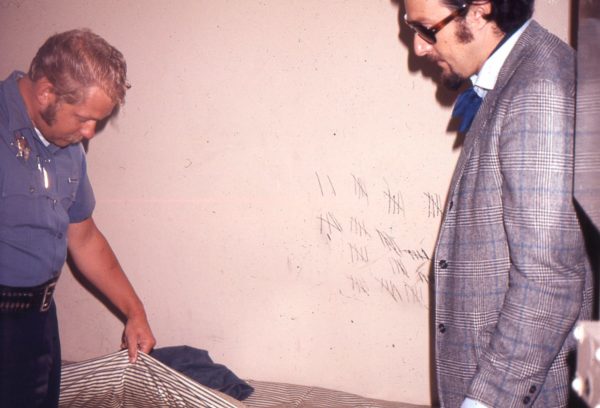

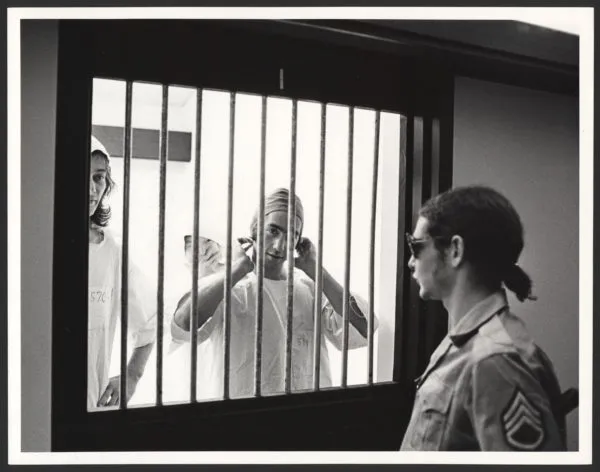

The study took paid participants and assigned them to be “inmates” or “guards” in a mock prison at Stanford University. Soon after the experiment began, the “guards” began mistreating the “prisoners,” implying evil is brought out by circumstance. The authors, in their conclusions, suggested innocent people, thrown into a situation where they have power over others, will begin to abuse that power. And people who are put into a situation where they are powerless will be driven to submission, even madness.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been included in many, many introductory psychology textbooks and is often cited uncritically . It’s the subject of movies, documentaries, books, television shows, and congressional testimony .

But its findings were wrong. Very wrong. And not just due to its questionable ethics or lack of concrete data — but because of deceit.

- Philip Zimbardo defends the Stanford Prison Experiment, his most famous work

A new exposé published by Medium based on previously unpublished recordings of Philip Zimbardo, the Stanford psychologist who ran the study, and interviews with his participants, offers convincing evidence that the guards in the experiment were coached to be cruel. It also shows that the experiment’s most memorable moment — of a prisoner descending into a screaming fit, proclaiming, “I’m burning up inside!” — was the result of the prisoner acting. “I took it as a kind of an improv exercise,” one of the guards told reporter Ben Blum . “I believed that I was doing what the researchers wanted me to do.”

The findings have long been subject to scrutiny — many think of them as more of a dramatic demonstration , a sort-of academic reality show, than a serious bit of science. But these new revelations incited an immediate response. “We must stop celebrating this work,” personality psychologist Simine Vazire tweeted , in response to the article . “It’s anti-scientific. Get it out of textbooks.” Many other psychologists have expressed similar sentiments.

( Update : Since this article published, the journal American Psychologist has published a thorough debunking of the Stanford Prison Experiment that goes beyond what Blum found in his piece. There’s even more evidence that the “guards” knew the results that Zimbardo wanted to produce, and were trained to meet his goals. It also provides evidence that the conclusions of the experiment were predetermined.)

Many of the classic show-stopping experiments in psychology have lately turned out to be wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. And in recent years, social scientists have begun to reckon with the truth that their old work needs a redo, the “ replication crisis .” But there’s been a lag — in the popular consciousness and in how psychology is taught by teachers and textbooks. It’s time to catch up.

Many classic findings in psychology have been reevaluated recently

The Zimbardo prison experiment is not the only classic study that has been recently scrutinized, reevaluated, or outright exposed as a fraud. Recently, science journalist Gina Perry found that the infamous “Robbers Cave“ experiment in the 1950s — in which young boys at summer camp were essentially manipulated into joining warring factions — was a do-over from a failed previous version of an experiment, which the scientists never mentioned in an academic paper. That’s a glaring omission. It’s wrong to throw out data that refutes your hypothesis and only publicize data that supports it.

Perry has also revealed inconsistencies in another major early work in psychology: the Milgram electroshock test, in which participants were told by an authority figure to deliver seemingly lethal doses of electricity to an unseen hapless soul. Her investigations show some evidence of researchers going off the study script and possibly coercing participants to deliver the desired results. (Somewhat ironically, the new revelations about the prison experiment also show the power an authority figure — in this case Zimbardo himself and his “warden” — has in manipulating others to be cruel.)

- The Stanford Prison Experiment is based on lies. Hear them for yourself.

Other studies have been reevaluated for more honest, methodological snafus. Recently, I wrote about the “marshmallow test,” a series of studies from the early ’90s that suggested the ability to delay gratification at a young age is correlated with success later in life . New research finds that if the original marshmallow test authors had a larger sample size, and greater research controls, their results would not have been the showstoppers they were in the ’90s. I can list so many more textbook psychology findings that have either not replicated, or are currently in the midst of a serious reevaluation.

- Social priming: People who read “old”-sounding words (like “nursing home”) were more likely to walk slowly — showing how our brains can be subtly “primed” with thoughts and actions.

- The facial feedback hypothesis: Merely activating muscles around the mouth caused people to become happier — demonstrating how our bodies tell our brains what emotions to feel.

- Stereotype threat: Minorities and maligned social groups don’t perform as well on tests due to anxieties about becoming a stereotype themselves.

- Ego depletion: The idea that willpower is a finite mental resource.

Alas, the past few years have brought about a reckoning for these ideas and social psychology as a whole.

Many psychological theories have been debunked or diminished in rigorous replication attempts. Psychologists are now realizing it’s more likely that false positives will make it through to publication than inconclusive results. And they’ve realized that experimental methods commonly used just a few years ago aren’t rigorous enough. For instance, it used to be commonplace for scientists to publish experiments that sampled about 50 undergraduate students. Today, scientists realize this is a recipe for false positives , and strive for sample sizes in the hundreds and ideally from a more representative subject pool.

Nevertheless, in so many of these cases, scientists have moved on and corrected errors, and are still doing well-intentioned work to understand the heart of humanity. For instance, work on one of psychology’s oldest fixations — dehumanization, the ability to see another as less than human — continues with methodological rigor, helping us understand the modern-day maltreatment of Muslims and immigrants in America.

In some cases, time has shown that flawed original experiments offer worthwhile reexamination. The original Milgram experiment was flawed. But at least its study design — which brings in participants to administer shocks (not actually carried out) to punish others for failing at a memory test — is basically repeatable today with some ethical tweaks.

And it seems like Milgram’s conclusions may hold up: In a recent study, many people found demands from an authority figure to be a compelling reason to shock another. However, it’s possible, due to something known as the file-drawer effect, that failed replications of the Milgram experiment have not been published. Replication attempts at the Stanford prison study, on the other hand, have been a mess .

In science, too often, the first demonstration of an idea becomes the lasting one — in both pop culture and academia. But this isn’t how science is supposed to work at all!

Science is a frustrating, iterative process. When we communicate it, we need to get beyond the idea that a single, stunning study ought to last the test of time. Scientists know this as well, but their institutions have often discouraged them from replicating old work, instead of the pursuit of new and exciting, attention-grabbing studies. (Journalists are part of the problem too , imbuing small, insignificant studies with more importance and meaning than they’re due.)

Thankfully, there are researchers thinking very hard, and very earnestly, on trying to make psychology a more replicable, robust science. There’s even a whole Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science devoted to these issues.

Follow-up results tend to be less dramatic than original findings , but they are more useful in helping discover the truth. And it’s not that the Stanford Prison Experiment has no place in a classroom. It’s interesting as history. Psychologists like Zimbardo and Milgram were highly influenced by World War II. Their experiments were, in part, an attempt to figure out why ordinary people would fall for Nazism. That’s an important question, one that set the agenda for a huge amount of research in psychological science, and is still echoed in papers today.

Textbooks need to catch up

Psychology has changed tremendously over the past few years. Many studies used to teach the next generation of psychologists have been intensely scrutinized, and found to be in error. But troublingly, the textbooks have not been updated accordingly .

That’s the conclusion of a 2016 study in Current Psychology. “ By and large,” the study explains (emphasis mine):

introductory textbooks have difficulty accurately portraying controversial topics with care or, in some cases, simply avoid covering them at all. ... readers of introductory textbooks may be unintentionally misinformed on these topics.

The study authors — from Texas A&M and Stetson universities — gathered a stack of 24 popular introductory psych textbooks and began looking for coverage of 12 contested ideas or myths in psychology.

The ideas — like stereotype threat, the Mozart effect , and whether there’s a “narcissism epidemic” among millennials — have not necessarily been disproven. Nevertheless, there are credible and noteworthy studies that cast doubt on them. The list of ideas also included some urban legends — like the one about the brain only using 10 percent of its potential at any given time, and a debunked story about how bystanders refused to help a woman named Kitty Genovese while she was being murdered.

The researchers then rated the texts on how they handled these contested ideas. The results found a troubling amount of “biased” coverage on many of the topic areas.

But why wouldn’t these textbooks include more doubt? Replication, after all, is a cornerstone of any science.

One idea is that textbooks, in the pursuit of covering a wide range of topics, aren’t meant to be authoritative on these individual controversies. But something else might be going on. The study authors suggest these textbook authors are trying to “oversell” psychology as a discipline, to get more undergraduates to study it full time. (I have to admit that it might have worked on me back when I was an undeclared undergraduate.)

There are some caveats to mention with the study: One is that the 12 topics the authors chose to scrutinize are completely arbitrary. “And many other potential issues were left out of our analysis,” they note. Also, the textbooks included were printed in the spring of 2012; it’s possible they have been updated since then.

Recently, I asked on Twitter how intro psychology professors deal with inconsistencies in their textbooks. Their answers were simple. Some say they decided to get rid of textbooks (which save students money) and focus on teaching individual articles. Others have another solution that’s just as simple: “You point out the wrong, outdated, and less-than-replicable sections,” Daniël Lakens , a professor at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, said. He offered a useful example of one of the slides he uses in class.

Anecdotally, Illinois State University professor Joe Hilgard said he thinks his students appreciate “the ‘cutting-edge’ feeling from knowing something that the textbook didn’t.” (Also, who really, earnestly reads the textbook in an introductory college course?)

And it seems this type of teaching is catching on. A (not perfectly representative) recent survey of 262 psychology professors found more than half said replication issues impacted their teaching . On the other hand, 40 percent said they hadn’t. So whether students are exposed to the recent reckoning is all up to the teachers they have.

If it’s true that textbooks and teachers are still neglecting to cover replication issues, then I’d argue they are actually underselling the science. To teach the “replication crisis” is to teach students that science strives to be self-correcting. It would instill in them the value that science ought to be reproducible.

Understanding human behavior is a hard problem. Finding out the answers shouldn’t be easy. If anything, that should give students more motivation to become the generation of scientists who get it right.

“Textbooks may be missing an opportunity for myth busting,” the Current Psychology study’s authors write. That’s, ideally, what young scientist ought to learn: how to bust myths and find the truth.

Further reading: Psychology’s “replication crisis”

- The replication crisis, explained. Psychology is currently undergoing a painful period of introspection. It will emerge stronger than before.

- The “marshmallow test” said patience was a key to success. A new replication tells us s’more.

- The 7 biggest problems facing science, according to 270 scientists

- What a nerdy debate about p-values shows about science — and how to fix it

- Science is often flawed. It’s time we embraced that.

Most Popular

- Scientists just discovered a sea creature as large as two basketball courts. Here’s what it looks like.

- Trump wants to use the military for mass deportations. Can he actually do that?

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- The House will have its first openly trans member next year. The GOP is already attacking her.

- The 2024 Future Perfect 50

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Science

Whatever you do, don’t call the Black in Neuro founder “resilient.”

Science should be bipartisan. Why is our confidence split down party lines?

Who owns the escaped monkeys now? It’s more complicated than you might think.

DMT, “the nuclear bomb of the psychedelic family,” explained.

How Musk’s SpaceX became too big to fail for US national security.

This research group is studying our love for haunted houses ... at a haunted house.

Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment

Affiliation.

- 1 Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis.

- PMID: 31380664

- DOI: 10.1037/amp0000401

The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) is one of psychology's most famous studies. It has been criticized on many grounds, and yet a majority of textbook authors have ignored these criticisms in their discussions of the SPE, thereby misleading both students and the general public about the study's questionable scientific validity. Data collected from a thorough investigation of the SPE archives and interviews with 15 of the participants in the experiment further question the study's scientific merit. These data are not only supportive of previous criticisms of the SPE, such as the presence of demand characteristics, but provide new criticisms of the SPE based on heretofore unknown information. These new criticisms include the biased and incomplete collection of data, the extent to which the SPE drew on a prison experiment devised and conducted by students in one of Zimbardo's classes 3 months earlier, the fact that the guards received precise instructions regarding the treatment of the prisoners, the fact that the guards were not told they were subjects, and the fact that participants were almost never completely immersed by the situation. Possible explanations of the inaccurate textbook portrayal and general misperception of the SPE's scientific validity over the past 5 decades, in spite of its flaws and shortcomings, are discussed. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2019 APA, all rights reserved).

Publication types

- Historical Article

- Data Collection / history

- Data Collection / standards*

- History, 20th Century

- Interpersonal Relations*

- Psychology, Social / history

- Psychology, Social / standards*

- Reproducibility of Results

- Research / history

- Research / standards*

- Social Behavior*

- Young Adult

Stanford Prison Experiment: Zimbardo’s Famous Study

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

- The experiment was conducted in 1971 by psychologist Philip Zimbardo to examine situational forces versus dispositions in human behavior.

- 24 young, healthy, psychologically normal men were randomly assigned to be “prisoners” or “guards” in a simulated prison environment.

- The experiment had to be terminated after only 6 days due to the extreme, pathological behavior emerging in both groups. The situational forces overwhelmed the dispositions of the participants.

- Pacifist young men assigned as guards began behaving sadistically, inflicting humiliation and suffering on the prisoners. Prisoners became blindly obedient and allowed themselves to be dehumanized.

- The principal investigator, Zimbardo, was also transformed into a rigid authority figure as the Prison Superintendent.

- The experiment demonstrated the power of situations to alter human behavior dramatically. Even good, normal people can do evil things when situational forces push them in that direction.

Zimbardo and his colleagues (1973) were interested in finding out whether the brutality reported among guards in American prisons was due to the sadistic personalities of the guards (i.e., dispositional) or had more to do with the prison environment (i.e., situational).

For example, prisoners and guards may have personalities that make conflict inevitable, with prisoners lacking respect for law and order and guards being domineering and aggressive.

Alternatively, prisoners and guards may behave in a hostile manner due to the rigid power structure of the social environment in prisons.

Zimbardo predicted the situation made people act the way they do rather than their disposition (personality).

To study people’s roles in prison situations, Zimbardo converted a basement of the Stanford University psychology building into a mock prison.

He advertised asking for volunteers to participate in a study of the psychological effects of prison life.

The 75 applicants who answered the ad were given diagnostic interviews and personality tests to eliminate candidates with psychological problems, medical disabilities, or a history of crime or drug abuse.

24 men judged to be the most physically & mentally stable, the most mature, & the least involved in antisocial behaviors were chosen to participate.

The participants did not know each other prior to the study and were paid $15 per day to take part in the experiment.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the role of prisoner or guard in a simulated prison environment. There were two reserves, and one dropped out, finally leaving ten prisoners and 11 guards.

Prisoners were treated like every other criminal, being arrested at their own homes, without warning, and taken to the local police station. They were fingerprinted, photographed and ‘booked.’

Then they were blindfolded and driven to the psychology department of Stanford University, where Zimbardo had had the basement set out as a prison, with barred doors and windows, bare walls and small cells. Here the deindividuation process began.

When the prisoners arrived at the prison they were stripped naked, deloused, had all their personal possessions removed and locked away, and were given prison clothes and bedding. They were issued a uniform, and referred to by their number only.

The use of ID numbers was a way to make prisoners feel anonymous. Each prisoner had to be called only by his ID number and could only refer to himself and the other prisoners by number.

Their clothes comprised a smock with their number written on it, but no underclothes. They also had a tight nylon cap to cover their hair, and a locked chain around one ankle.

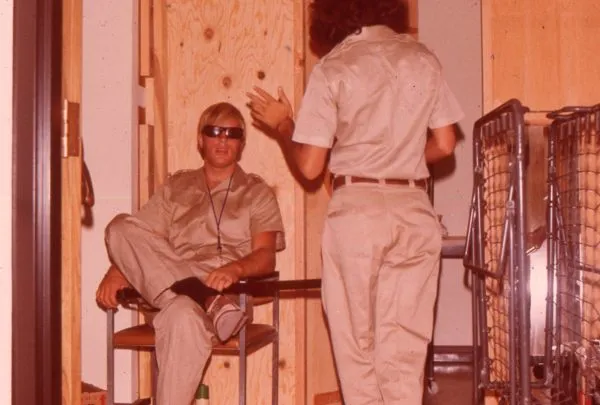

All guards were dressed in identical uniforms of khaki, and they carried a whistle around their neck and a billy club borrowed from the police. Guards also wore special sunglasses, to make eye contact with prisoners impossible.

Three guards worked shifts of eight hours each (the other guards remained on call). Guards were instructed to do whatever they thought was necessary to maintain law and order in the prison and to command the respect of the prisoners. No physical violence was permitted.

Zimbardo observed the behavior of the prisoners and guards (as a researcher), and also acted as a prison warden.

Within a very short time both guards and prisoners were settling into their new roles, with the guards adopting theirs quickly and easily.

Asserting Authority

Within hours of beginning the experiment, some guards began to harass prisoners. At 2:30 A.M. prisoners were awakened from sleep by blasting whistles for the first of many “counts.”

The counts served as a way to familiarize the prisoners with their numbers. More importantly, they provided a regular occasion for the guards to exercise control over the prisoners.

The prisoners soon adopted prisoner-like behavior too. They talked about prison issues a great deal of the time. They ‘told tales’ on each other to the guards.

They started taking the prison rules very seriously, as though they were there for the prisoners’ benefit and infringement would spell disaster for all of them. Some even began siding with the guards against prisoners who did not obey the rules.

Physical Punishment

The prisoners were taunted with insults and petty orders, they were given pointless and boring tasks to accomplish, and they were generally dehumanized.

Push-ups were a common form of physical punishment imposed by the guards. One of the guards stepped on the prisoners” backs while they did push-ups, or made other prisoners sit on the backs of fellow prisoners doing their push-ups.

Asserting Independence

Because the first day passed without incident, the guards were surprised and totally unprepared for the rebellion which broke out on the morning of the second day.

During the second day of the experiment, the prisoners removed their stocking caps, ripped off their numbers, and barricaded themselves inside the cells by putting their beds against the door.

The guards called in reinforcements. The three guards who were waiting on stand-by duty came in and the night shift guards voluntarily remained on duty.

Putting Down the Rebellion

The guards retaliated by using a fire extinguisher which shot a stream of skin-chilling carbon dioxide, and they forced the prisoners away from the doors. Next, the guards broke into each cell, stripped the prisoners naked and took the beds out.

The ringleaders of the prisoner rebellion were placed into solitary confinement. After this, the guards generally began to harass and intimidate the prisoners.

Special Privileges

One of the three cells was designated as a “privilege cell.” The three prisoners least involved in the rebellion were given special privileges. The guards gave them back their uniforms and beds and allowed them to wash their hair and brush their teeth.

Privileged prisoners also got to eat special food in the presence of the other prisoners who had temporarily lost the privilege of eating. The effect was to break the solidarity among prisoners.

Consequences of the Rebellion

Over the next few days, the relationships between the guards and the prisoners changed, with a change in one leading to a change in the other. Remember that the guards were firmly in control and the prisoners were totally dependent on them.

As the prisoners became more dependent, the guards became more derisive towards them. They held the prisoners in contempt and let the prisoners know it. As the guards’ contempt for them grew, the prisoners became more submissive.

As the prisoners became more submissive, the guards became more aggressive and assertive. They demanded ever greater obedience from the prisoners. The prisoners were dependent on the guards for everything, so tried to find ways to please the guards, such as telling tales on fellow prisoners.

Prisoner #8612

Less than 36 hours into the experiment, Prisoner #8612 began suffering from acute emotional disturbance, disorganized thinking, uncontrollable crying, and rage.

After a meeting with the guards where they told him he was weak, but offered him “informant” status, #8612 returned to the other prisoners and said “You can”t leave. You can’t quit.”

Soon #8612 “began to act ‘crazy,’ to scream, to curse, to go into a rage that seemed out of control.” It wasn’t until this point that the psychologists realized they had to let him out.

A Visit from Parents

The next day, the guards held a visiting hour for parents and friends. They were worried that when the parents saw the state of the jail, they might insist on taking their sons home. Guards washed the prisoners, had them clean and polish their cells, fed them a big dinner and played music on the intercom.

After the visit, rumors spread of a mass escape plan. Afraid that they would lose the prisoners, the guards and experimenters tried to enlist help and facilities of the Palo Alto police department.

The guards again escalated the level of harassment, forcing them to do menial, repetitive work such as cleaning toilets with their bare hands.

Catholic Priest

Zimbardo invited a Catholic priest who had been a prison chaplain to evaluate how realistic our prison situation was. Half of the prisoners introduced themselves by their number rather than name.

The chaplain interviewed each prisoner individually. The priest told them the only way they would get out was with the help of a lawyer.

Prisoner #819

Eventually, while talking to the priest, #819 broke down and began to cry hysterically, just like two previously released prisoners had.

The psychologists removed the chain from his foot, the cap off his head, and told him to go and rest in a room that was adjacent to the prison yard. They told him they would get him some food and then take him to see a doctor.

While this was going on, one of the guards lined up the other prisoners and had them chant aloud:

“Prisoner #819 is a bad prisoner. Because of what Prisoner #819 did, my cell is a mess, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

The psychologists realized #819 could hear the chanting and went back into the room where they found him sobbing uncontrollably. The psychologists tried to get him to agree to leave the experiment, but he said he could not leave because the others had labeled him a bad prisoner.

Back to Reality

At that point, Zimbardo said, “Listen, you are not #819. You are [his name], and my name is Dr. Zimbardo. I am a psychologist, not a prison superintendent, and this is not a real prison. This is just an experiment, and those are students, not prisoners, just like you. Let’s go.”

He stopped crying suddenly, looked up and replied, “Okay, let’s go,“ as if nothing had been wrong.

An End to the Experiment

Zimbardo (1973) had intended that the experiment should run for two weeks, but on the sixth day, it was terminated, due to the emotional breakdowns of prisoners, and excessive aggression of the guards.

Christina Maslach, a recent Stanford Ph.D. brought in to conduct interviews with the guards and prisoners, strongly objected when she saw the prisoners being abused by the guards.

Filled with outrage, she said, “It’s terrible what you are doing to these boys!” Out of 50 or more outsiders who had seen our prison, she was the only one who ever questioned its morality.

Zimbardo (2008) later noted, “It wasn’t until much later that I realized how far into my prison role I was at that point — that I was thinking like a prison superintendent rather than a research psychologist.“

This led him to prioritize maintaining the experiment’s structure over the well-being and ethics involved, thereby highlighting the blurring of roles and the profound impact of the situation on human behavior.

Here’s a quote that illustrates how Philip Zimbardo, initially the principal investigator, became deeply immersed in his role as the “Stanford Prison Superintendent (April 19, 2011):

“By the third day, when the second prisoner broke down, I had already slipped into or been transformed into the role of “Stanford Prison Superintendent.” And in that role, I was no longer the principal investigator, worried about ethics. When a prisoner broke down, what was my job? It was to replace him with somebody on our standby list. And that’s what I did. There was a weakness in the study in not separating those two roles. I should only have been the principal investigator, in charge of two graduate students and one undergraduate.”

According to Zimbardo and his colleagues, the Stanford Prison Experiment revealed how people will readily conform to the social roles they are expected to play, especially if the roles are as strongly stereotyped as those of the prison guards.

Because the guards were placed in a position of authority, they began to act in ways they would not usually behave in their normal lives.

The “prison” environment was an important factor in creating the guards’ brutal behavior (none of the participants who acted as guards showed sadistic tendencies before the study).

Therefore, the findings support the situational explanation of behavior rather than the dispositional one.

Zimbardo proposed that two processes can explain the prisoner’s “final submission.”

Deindividuation may explain the behavior of the participants; especially the guards. This is a state when you become so immersed in the norms of the group that you lose your sense of identity and personal responsibility.

The guards may have been so sadistic because they did not feel what happened was down to them personally – it was a group norm. They also may have lost their sense of personal identity because of the uniform they wore.

Also, learned helplessness could explain the prisoner’s submission to the guards. The prisoners learned that whatever they did had little effect on what happened to them. In the mock prison the unpredictable decisions of the guards led the prisoners to give up responding.

After the prison experiment was terminated, Zimbardo interviewed the participants. Here’s an excerpt:

‘Most of the participants said they had felt involved and committed. The research had felt “real” to them. One guard said, “I was surprised at myself. I made them call each other names and clean the toilets out with their bare hands. I practically considered the prisoners cattle and I kept thinking I had to watch out for them in case they tried something.” Another guard said “Acting authoritatively can be fun. Power can be a great pleasure.” And another: “… during the inspection I went to Cell Two to mess up a bed which a prisoner had just made and he grabbed me, screaming that he had just made it and that he was not going to let me mess it up. He grabbed me by the throat and although he was laughing I was pretty scared. I lashed out with my stick and hit him on the chin although not very hard, and when I freed myself I became angry.”’

Most of the guards found it difficult to believe that they had behaved in the brutal ways that they had. Many said they hadn’t known this side of them existed or that they were capable of such things.

The prisoners, too, couldn’t believe that they had responded in the submissive, cowering, dependent way they had. Several claimed to be assertive types normally.

When asked about the guards, they described the usual three stereotypes that can be found in any prison: some guards were good, some were tough but fair, and some were cruel.

A further explanation for the behavior of the participants can be described in terms of reinforcement. The escalation of aggression and abuse by the guards could be seen as being due to the positive reinforcement they received both from fellow guards and intrinsically in terms of how good it made them feel to have so much power.

Similarly, the prisoners could have learned through negative reinforcement that if they kept their heads down and did as they were told, they could avoid further unpleasant experiences.

Critical Evaluation

Ecological validity.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is criticized for lacking ecological validity in its attempt to simulate a real prison environment. Specifically, the “prison” was merely a setup in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology department.

The student “guards” lacked professional training, and the experiment’s duration was much shorter than real prison sentences. Furthermore, the participants, who were college students, didn’t reflect the diverse backgrounds typically found in actual prisons in terms of ethnicity, education, and socioeconomic status.

None had prior prison experience, and they were chosen due to their mental stability and low antisocial tendencies. Additionally, the mock prison lacked spaces for exercise or rehabilitative activities.

Demand characteristics

Demand characteristics could explain the findings of the study. Most of the guards later claimed they were simply acting. Because the guards and prisoners were playing a role, their behavior may not be influenced by the same factors which affect behavior in real life. This means the study’s findings cannot be reasonably generalized to real life, such as prison settings. I.e, the study has low ecological validity.

One of the biggest criticisms is that strong demand characteristics confounded the study. Banuazizi and Movahedi (1975) found that the majority of respondents, when given a description of the study, were able to guess the hypothesis and predict how participants were expected to behave.

This suggests participants may have simply been playing out expected roles rather than genuinely conforming to their assigned identities.

In addition, revelations by Zimbardo (2007) indicate he actively encouraged the guards to be cruel and oppressive in his orientation instructions prior to the start of the study. For example, telling them “they [the prisoners] will be able to do nothing and say nothing that we don’t permit.”

He also tacitly approved of abusive behaviors as the study progressed. This deliberate cueing of how participants should act, rather than allowing behavior to unfold naturally, indicates the study findings were likely a result of strong demand characteristics rather than insightful revelations about human behavior.

However, there is considerable evidence that the participants did react to the situation as though it was real. For example, 90% of the prisoners’ private conversations, which were monitored by the researchers, were on the prison conditions, and only 10% of the time were their conversations about life outside of the prison.

The guards, too, rarely exchanged personal information during their relaxation breaks – they either talked about ‘problem prisoners,’ other prison topics, or did not talk at all. The guards were always on time and even worked overtime for no extra pay.

When the prisoners were introduced to a priest, they referred to themselves by their prison number, rather than their first name. Some even asked him to get a lawyer to help get them out.

Fourteen years after his experience as prisoner 8612 in the Stanford Prison Experiment, Douglas Korpi, now a prison psychologist, reflected on his time and stated (Musen and Zimbardo 1992):

“The Stanford Prison Experiment was a very benign prison situation and it promotes everything a normal prison promotes — the guard role promotes sadism, the prisoner role promotes confusion and shame”.

Sample bias

The study may also lack population validity as the sample comprised US male students. The study’s findings cannot be applied to female prisons or those from other countries. For example, America is an individualist culture (where people are generally less conforming), and the results may be different in collectivist cultures (such as Asian countries).

Carnahan and McFarland (2007) have questioned whether self-selection may have influenced the results – i.e., did certain personality traits or dispositions lead some individuals to volunteer for a study of “prison life” in the first place?

All participants completed personality measures assessing: aggression, authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, narcissism, social dominance, empathy, and altruism. Participants also answered questions on mental health and criminal history to screen out any issues as per the original SPE.

Results showed that volunteers for the prison study, compared to the control group, scored significantly higher on aggressiveness, authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, narcissism, and social dominance. They scored significantly lower on empathy and altruism.

A follow-up role-playing study found that self-presentation biases could not explain these differences. Overall, the findings suggest that volunteering for the prison study was influenced by personality traits associated with abusive tendencies.

Zimbardo’s conclusion may be wrong

While implications for the original SPE are speculative, this lends support to a person-situation interactionist perspective, rather than a purely situational account.

It implies that certain individuals are drawn to and selected into situations that fit their personality, and that group composition can shape behavior through mutual reinforcement.

Contributions to psychology

Another strength of the study is that the harmful treatment of participants led to the formal recognition of ethical guidelines by the American Psychological Association. Studies must now undergo an extensive review by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) before they are implemented.

Most institutions, such as universities, hospitals, and government agencies, require a review of research plans by a panel. These boards review whether the potential benefits of the research are justifiable in light of the possible risk of physical or psychological harm.

These boards may request researchers make changes to the study’s design or procedure, or, in extreme cases, deny approval of the study altogether.

Contribution to prison policy

A strength of the study is that it has altered the way US prisons are run. For example, juveniles accused of federal crimes are no longer housed before trial with adult prisoners (due to the risk of violence against them).

However, in the 25 years since the SPE, U.S. prison policy has transformed in ways counter to SPE insights (Haney & Zimbardo, 1995):

- Rehabilitation was abandoned in favor of punishment and containment. Prison is now seen as inflicting pain rather than enabling productive re-entry.

- Sentencing became rigid rather than accounting for inmates’ individual contexts. Mandatory minimums and “three strikes” laws over-incarcerate nonviolent crimes.

- Prison construction boomed, and populations soared, disproportionately affecting minorities. From 1925 to 1975, incarceration rates held steady at around 100 per 100,000. By 1995, rates tripled to over 600 per 100,000.

- Drug offenses account for an increasing proportion of prisoners. Nonviolent drug offenses make up a large share of the increased incarceration.

- Psychological perspectives have been ignored in policymaking. Legislators overlooked insights from social psychology on the power of contexts in shaping behavior.

- Oversight retreated, with courts deferring to prison officials and ending meaningful scrutiny of conditions. Standards like “evolving decency” gave way to “legitimate” pain.

- Supermax prisons proliferated, isolating prisoners in psychological trauma-inducing conditions.

The authors argue psychologists should reengage to:

- Limit the use of imprisonment and adopt humane alternatives based on the harmful effects of prison environments

- Assess prisons’ total environments, not just individual conditions, given situational forces interact

- Prepare inmates for release by transforming criminogenic post-release contexts

- Address socioeconomic risk factors, not just incarcerate individuals

- Develop contextual prediction models vs. focusing only on static traits

- Scrutinize prison systems independently, not just defer to officials shaped by those environments

- Generate creative, evidence-based reforms to counter over-punitive policies

Psychology once contributed to a more humane system and can again counter the U.S. “rage to punish” with contextual insights (Haney & Zimbardo, 1998).

Evidence for situational factors

Zimbardo (1995) further demonstrates the power of situations to elicit evil actions from ordinary, educated people who likely would never have done such things otherwise. It was another situation-induced “transformation of human character.”

- Unit 731 was a covert biological and chemical warfare research unit of the Japanese army during WWII.

- It was led by General Shiro Ishii and involved thousands of doctors and researchers.

- Unit 731 set up facilities near Harbin, China to conduct lethal human experimentation on prisoners, including Allied POWs.

- Experiments involved exposing prisoners to things like plague, anthrax, mustard gas, and bullets to test biological weapons. They infected prisoners with diseases and monitored their deaths.

- At least 3,000 prisoners died from these brutal experiments. Many were killed and dissected.

- The doctors in Unit 731 obeyed orders unquestioningly and conducted these experiments in the name of “medical science.”

- After the war, the vast majority of doctors who participated faced no punishment and went on to have prestigious careers. This was largely covered up by the U.S. in exchange for data.

- It shows how normal, intelligent professionals can be led by situational forces to systematically dehumanize victims and conduct incredibly cruel and lethal experiments on people.

- Even healers trained to preserve life used their expertise to destroy lives when the situational forces compelled obedience, nationalism, and wartime enmity.

Evidence for an interactionist approach

The results are also relevant for explaining abuses by American guards at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

An interactionist perspective recognizes that volunteering for roles as prison guards attracts those already prone to abusive tendencies, which are intensified by the prison context.

This counters a solely situationist view of good people succumbing to evil situational forces.

Ethical Issues

The study has received many ethical criticisms, including lack of fully informed consent by participants as Zimbardo himself did not know what would happen in the experiment (it was unpredictable). Also, the prisoners did not consent to being “arrested” at home. The prisoners were not told partly because final approval from the police wasn’t given until minutes before the participants decided to participate, and partly because the researchers wanted the arrests to come as a surprise. However, this was a breach of the ethics of Zimbardo’s own contract that all of the participants had signed.

Protection of Participants

Participants playing the role of prisoners were not protected from psychological harm, experiencing incidents of humiliation and distress. For example, one prisoner had to be released after 36 hours because of uncontrollable bursts of screaming, crying, and anger.

Here’s a quote from Philip G. Zimbardo, taken from an interview on the Stanford Prison Experiment’s 40th anniversary (April 19, 2011):

“In the Stanford prison study, people were stressed, day and night, for 5 days, 24 hours a day. There’s no question that it was a high level of stress because five of the boys had emotional breakdowns, the first within 36 hours. Other boys that didn’t have emotional breakdowns were blindly obedient to corrupt authority by the guards and did terrible things to each other. And so it is no question that that was unethical. You can’t do research where you allow people to suffer at that level.”

“After the first one broke down, we didn’t believe it. We thought he was faking. There was actually a rumor he was faking to get out. He was going to bring his friends in to liberate the prison. And/or we believed our screening procedure was inadequate, [we believed] that he had some mental defect that we did not pick up. At that point, by the third day, when the second prisoner broke down, I had already slipped into or been transformed into the role of “Stanford Prison Superintendent.” And in that role, I was no longer the principal investigator, worried about ethics.”

However, in Zimbardo’s defense, the emotional distress experienced by the prisoners could not have been predicted from the outset.

Approval for the study was given by the Office of Naval Research, the Psychology Department, and the University Committee of Human Experimentation.

This Committee also did not anticipate the prisoners’ extreme reactions that were to follow. Alternative methodologies were looked at that would cause less distress to the participants but at the same time give the desired information, but nothing suitable could be found.

Withdrawal

Although guards were explicitly instructed not to physically harm prisoners at the beginning of the Stanford Prison Experiment, they were allowed to induce feelings of boredom, frustration, arbitrariness, and powerlessness among the inmates.

This created a pervasive atmosphere where prisoners genuinely believed and even reinforced among each other, that they couldn’t leave the experiment until their “sentence” was completed, mirroring the inescapability of a real prison.

Even though two participants (8612 and 819) were released early, the impact of the environment was so profound that prisoner 416, reflecting on the experience two months later, described it as a “prison run by psychologists rather than by the state.”

Extensive group and individual debriefing sessions were held, and all participants returned post-experimental questionnaires several weeks, then several months later, and then at yearly intervals. Zimbardo concluded there were no lasting negative effects.

Zimbardo also strongly argues that the benefits gained from our understanding of human behavior and how we can improve society should outbalance the distress caused by the study.

However, it has been suggested that the US Navy was not so much interested in making prisons more human and were, in fact, more interested in using the study to train people in the armed services to cope with the stresses of captivity.

Discussion Questions

What are the effects of living in an environment with no clocks, no view of the outside world, and minimal sensory stimulation?

Consider the psychological consequences of stripping, delousing, and shaving the heads of prisoners or members of the military. Whattransformations take place when people go through an experience like this?

The prisoners could have left at any time, and yet, they didn’t. Why?

After the study, how do you think the prisoners and guards felt?

If you were the experimenter in charge, would you have done this study? Would you have terminated it earlier? Would you have conducted a follow-up study?

Frequently Asked Questions

What happened to prisoner 8612 after the experiment.

Douglas Korpi, as prisoner 8612, was the first to show signs of severe distress and demanded to be released from the experiment. He was released on the second day, and his reaction to the simulated prison environment highlighted the study’s ethical issues and the potential harm inflicted on participants.

After the experiment, Douglas Korpi graduated from Stanford University and earned a Ph.D. in clinical psychology. He pursued a career as a psychotherapist, helping others with their mental health struggles.

Why did Zimbardo not stop the experiment?

Zimbardo did not initially stop the experiment because he became too immersed in his dual role as the principal investigator and the prison superintendent, causing him to overlook the escalating abuse and distress among participants.

It was only after an external observer, Christina Maslach, raised concerns about the participants’ well-being that Zimbardo terminated the study.

What happened to the guards in the Stanford Prison Experiment?

In the Stanford Prison Experiment, the guards exhibited abusive and authoritarian behavior, using psychological manipulation, humiliation, and control tactics to assert dominance over the prisoners. This ultimately led to the study’s early termination due to ethical concerns.

What did Zimbardo want to find out?

Zimbardo aimed to investigate the impact of situational factors and power dynamics on human behavior, specifically how individuals would conform to the roles of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison environment.

He wanted to explore whether the behavior displayed in prisons was due to the inherent personalities of prisoners and guards or the result of the social structure and environment of the prison itself.

What were the results of the Stanford Prison Experiment?

The results of the Stanford Prison Experiment showed that situational factors and power dynamics played a significant role in shaping participants’ behavior. The guards became abusive and authoritarian, while the prisoners became submissive and emotionally distressed.

The experiment revealed how quickly ordinary individuals could adopt and internalize harmful behaviors due to their assigned roles and the environment.

Banuazizi, A., & Movahedi, S. (1975). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison: A methodological analysis. American Psychologist, 30 , 152-160.

Carnahan, T., & McFarland, S. (2007). Revisiting the Stanford prison experiment: Could participant self-selection have led to the cruelty? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 603-614.

Drury, S., Hutchens, S. A., Shuttlesworth, D. E., & White, C. L. (2012). Philip G. Zimbardo on his career and the Stanford Prison Experiment’s 40th anniversary. History of Psychology , 15 (2), 161.

Griggs, R. A., & Whitehead, G. I., III. (2014). Coverage of the Stanford Prison Experiment in introductory social psychology textbooks. Teaching of Psychology, 41 , 318 –324.

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison . Naval Research Review , 30, 4-17.

Haney, C., & Zimbardo, P. (1998). The past and future of U.S. prison policy: Twenty-five years after the Stanford Prison Experiment. American Psychologist, 53 (7), 709–727.

Musen, K. & Zimbardo, P. (1992) (DVD) Quiet Rage: The Stanford Prison Experiment Documentary.

Zimbardo, P. G. (Consultant, On-Screen Performer), Goldstein, L. (Producer), & Utley, G. (Correspondent). (1971, November 26). Prisoner 819 did a bad thing: The Stanford Prison Experiment [Television series episode]. In L. Goldstein (Producer), Chronolog. New York, NY: NBC-TV.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). On the ethics of intervention in human psychological research: With special reference to the Stanford prison experiment. Cognition , 2 (2), 243-256.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1995). The psychology of evil: A situationist perspective on recruiting good people to engage in anti-social acts. Japanese Journal of Social Psychology , 11 (2), 125-133.

Zimbardo, P.G. (2007). The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil . New York, NY: Random House.

Further Information

- Reicher, S., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC prison study. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 45 , 1.

- Coverage of the Stanford Prison Experiment in introductory psychology textbooks

- The Stanford Prison Experiment Official Website

- Biz & IT

Revisiting the Stanford Prison Experiment 50 years later

Ars chats with director Juliette Eisner and original study participants in new documentary series.

In 1971, Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo conducted a notorious experiment in which he randomly divided college students into two groups, guards and prisoners, and set them loose in a simulated prison environment for six days, documenting the guards' descent into brutality. His findings caused a media sensation and a lot of subsequent criticism about the ethics and methodology employed in the study. Zimbardo died last month at 91, but his controversial legacy continues to resonate some 50 years later with The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth , a new documentary from National Geographic.

Director Juliette Eisner started working on the documentary during the pandemic when, like most people, she had a lot of extra time on her hands. She started looking at old psychological studies exploring human nature and became fascinated by the Stanford Prison Experiment, especially in light of the summer protests in 2020 concerning police brutality. She soon realized that the prevailing narrative was Zimbardo's and that very few of the original subjects in the experiment had ever been interviewed about their experiences.

"I wanted to hear from those people," Eisner told Ars. "They were very hard to find. Most of them were still only known by alias or by prisoner number." Eisner persevered and tracked most of them down. "Every single time they picked up the phone, they were like, 'Oh, I'm so glad you called. Nobody has called me in 50 years. And by the way, everything you think you know about this study is wrong,' or 'The story is not what it seems.'"

Her original intention was to debunk the experiment, but over the course of making the documentary, her focus shifted to the power of storytelling. "Even when stories are riddled with lies or manipulations, they can still capture our imaginations in ways that we should maybe be wary of sometimes," Eisner said, particularly when those stories "come out of the mouth of somebody who is such a showman, such an entertainer."

The documentary's structure reflects Eisner's research journey. The first episode ("The Hallway") focuses on the standard account of the experiment that has dominated for the last 50 years. The second ("The Unraveling") focuses on subsequent criticisms and debunkings and the accounts of original participants, many of whom have rather different takes. The third episode ("A Beautiful Lie") brings the original participants to Los Angeles for a re-enactment with professional actors and includes an interview with Zimbardo himself.

"We grappled with the structure and how to let the story unfold and decided, let's tell the audience what they think they know, and then let's take it apart," said Eisner. "And then a surprise twist, let's give you a different look at it and let the man at the center of it all defend the experiment against these claims. It was really important to me to have all these perspectives be heard, and not just one person's story as it had been for the past 50 years. Everybody had a different take on this experiment, even though they all lived it together."

For the re-enactment, NatGeo commissioned a set based on the floor plans of the Stanford basement where the original experiment was conducted. "We really needed visuals to help bring a lot of these stories to life," said Eisner. "Despite the fact that Zimbardo says he filmed the whole thing, he really only filmed six hours over the course of six days. So we needed that visual toolbox, but then it also allowed us to play with these different perspectives."

A controversial experiment

Zimbardo's research involved de-individuation and dehumanization in the context of what drives people to engage in antisocial and/or brutal acts that they would normally find morally repugnant. He designed the Stanford Prison Experiment specifically to investigate the power of roles, rules, group identity, and "situational validation of behavior." He recruited the participants via help wanted ads in the local newspapers and selected 24 young men from the 75 who applied. All were screened for criminal backgrounds, psychological problems, and physical health.

The experiment was conducted in the basement of Jordan Hall. A small corridor served as the prison yard; a janitor's closet was used for solitary confinement ("the Hole"); there were several mock prison cells designed to hold three prisoners each with cots, mattresses, and sheets; and a bigger room housed the guards and the prison warden (Zimbardo's undergraduate research assistant David Jaffe). The guards worked eight-hour shifts and were allowed to leave the site; prisoners had to remain 24/7.

The experiment officially kicked off when the Palo Alto police conducted mock arrests of those participants designated as prisoners—something the latter was not told would happen and a breach of ethics. After being booked, fingerprinted, and sitting for mugshots, they were strip-searched and made to wear smocks with no underwear and stocking caps on their heads. Over the next six days, the guards psychologically tormented their charges with sleep disruption, spraying rebellious prisoners with a fire extinguisher, removing mattresses as punishment, forcing prisoners to drop for pushups, restricting bathroom access so that prisoners had to relieve themselves in a bucket in their cells, and so on—all accompanied by constant verbal abuse.

After 36 hours, it became too much for a prisoner named Doug Korpi ("Prisoner 8612"), who had been tossed into the Hole for insubordination. He underwent what seemed to be a mental breakdown, causing him to be released early from the experiment. On Day 5, friends and family were allowed to visit for 10 minutes; those visits were sufficiently upsetting that several parents intended to contact lawyers to get their children released from the experiment. Zimbardo's fellow psychologist and then-girlfriend, Christina Maslach, also visited the setup and was so appalled she sharply chided Zimbardo for his lack of oversight and called the experiment immoral. Zimbardo decided to end the experiment on Day 6.

One positive outcome was that the Stanford Prison Experiment led US universities to overhaul their ethical requirements for any experiments involving human subjects. But many researchers were troubled both by the methodology and the simplicity of Zimbardo's interpretations. French researcher Thibault Le Texier has been among the strongest critics, pointing out that many of Zimbardo's conclusions were written out in advance, and the experiment was carefully manipulated to produce the results Zimbardo wanted. Zimbardo dismissed Le Texier's work as an ad hominem attack that ignores any contradictory data, but the original participants interviewed for the NatGeo documentary largely confirmed many of Le Texier's claims.

Playing to the camera?

Former prisoner Clay Ramsay, for instance, replaced Korpi in the experiment and quickly became disillusioned with the situation. "It had no intellectual integrity at all," he told Ars, noting that this was particularly obvious during the staged parole board hearings the prisoners were forced to participate in. "They clearly didn't have any kind of common script," he said. "So I came up with the idea of a hunger strike, and then most of my behavior was doing nothing. It turned out to be more dramatic than it had to be."

He ended up tossed in "the Hole" for his insubordination, but rather than being traumatized, he took advantage of the isolation to grab some shut-eye to make up for all the sleep deprivation. "It's supposed to be this major penalty, then it's the only place where you can get a night's sleep in the whole joint," he said.

While Zimbardo has repeatedly insisted over five decades that he simply put college kids into a situation with little guidance and just let things evolve, that's not entirely true. The guards, most notably, participated in a lengthy training session that lasted several hours, in which they were given a daily schedule for the prisoners and tips for inflicting psychological pain, starting by referring to prisoners by number rather than name as a means of dehumanizing them.

Zimbardo also occasionally allowed members of his research team to go into the experimental environment; there is even audio of research assistant David Jaffe coaching a reluctant guard and urging him to be tougher in his treatment of the prisoners. This led many of the guards to assume they were not part of the actual experiment but were in league with the researchers.

"It was made very clear to us that we not part of the experiment," former guard Dave Eshleman told Ars. "We were there to help the researchers get the results from the prisoners that they wanted to see. So our job was to make them uncomfortable, give them a sense of fear, but not to use physical violence. We could do everything else within our power to create that fear, and I took that very seriously, because I was on board with what they were trying to do: expose the prison system as evil. Given the zeitgeist at the time, we were all on board with that. Those were the days when anybody with the establishment was automatically evil, and what more evil part of the establishment could there be but the prison system?"

There are also valid questions about whether or not the prisoners' behavior was truly authentic. Doug Korpi later claimed he faked his mental breakdown in the Hole, having become disillusioned with the study. He had thought it would give him some downtime to study for the Graduate Record Exam, but the guards wouldn't allow it. So he staged a breakdown to secure his release.

Korpi was not alone in this. Despite being the poster boy for the guards' collective brutality, "I was absolutely playing for the camera," said Eshleman. "I knew where the camera was, I knew that it was on most of the time, I could hear the researchers talking behind the wall. I was also an acting student and did a lot of improv exercises. So I treated this is an improv, and I created my character based on what my understanding was of what the researchers wanted from us." He based his character on Strother Martin, the fictional evil prison warden from Cool Hand Luke (1967); Eshleman even occasionally spoke actual lines from the film, and his antics earned him the moniker "John Wayne."

Ramsay's experience as a prisoner was a bit different. "I don't think any of the prisoners were conscious of the camera, honestly," he told Ars. "We were not entirely sure where it was, we thought we saw it sometimes. But we were not getting regular instructions, we were being fed badly, clothed badly, et cetera. In a situation like that, what the camera angle is, it's the least of your worries."

In retrospect, the Stanford Prison Experiment may have more in common with reality TV; the industry term has evolved into "unscripted" TV because of the countless ways the final product is manipulated and shaped over the course of filming. Zimbardo even admits as much in the documentary, calling his experiment "the first ever reality TV show."

Controlling the narrative

Zimbardo's version of events has long dominated the prevailing understanding of the Stanford Prison Experiment, even though some of the original participants have frequently tried to counter that narrative; their voices just never held as much sway. While Eshleman has participated in many media interviews over the ensuing decades, he said that much of his commentary was often edited out in favor of Zimbardo's preferred narrative.

For his part, Zimbardo has said repeatedly that Korpi, for instance, was lying about faking his breakdown, pointing to the fact that Korpi became a prison psychologist because of how deeply the experiment affected him. Zimbardo also denies in the NatGeo documentary that Eshleman was acting for the duration of the experiment; his interpretation is that this is how Eshleman rationalized his behavior and dealt with the guilt.

"I think I knew if I was acting or not," Eshleman countered. "How could he not even consider the possibility that not just I, but everybody in his little demonstration was acting, that we simply fell into roles that were expected of us, to be paid $15 a day? That's what galls me. He kind of decided to throw us [the guards] under the bus after directing us to do what he wanted. Maybe he never took an acting class. Those of those in the theater department are always acting in some way." In fact, the basic scenario of the Stanford Prison Experiment has found its way into many improv classes as an exercise prompt.

"I was very fortunate that Zimbardo never really got into characterizing me," said Ramsay. "But for Dave and two or three of the others, he did. He put labels on them, ascribed motivations, and went, 'I'm a professor of psychology at Stanford University. Are you going to listen to me or to them who are driven by unconscious needs?' A lifetime of that is really insulting."

Eisner admitted that her experiences making the documentary produced some complicated feelings about the Stanford Prison Experiment. "I think that it's absolutely clear there was no scientific methodology," she said. "The data was all over the place, if you can even call it data. I think it's wrong to frame it as such. But do I think the big picture questions it asks are not true, that power does not corrupt? No, I don't think so. I've spent far too many years working on documentaries about fraud and felonies not to know that power can corrupt. But I do think it's dangerous to call to a faulty experiment in order to try to prove those things."

"I really do think there was nothing genuinely malicious in what Zimbardo was doing," said Eisner. "I wish he had been more forthcoming about certain things that he definitely glossed over. But is the experiment important? Absolutely. I love that it has this life 50 years later where now we're looking at it and re-contextualizing it in a way that is totally different from back when he actually did the study."

Ramsay and Eshleman are less charitable in their assessments. "This was the chosen vessel of Zimbardo's ambition and his extraordinary PR skills," said Ramsay. "Because that was his real gift, much more than academic research. He could drive a story, and this was the one that made his career. It gave him fame and notoriety at the same time. It's a package that he drove over the needs, requirements, and values of everybody else involved throughout his life."

"He was not somebody we felt we could question at the time," said Eshleman. "It was only later that I looked back and said, 'It was good theater, but it was not good science.' There were no controls. The conclusions that supposedly came out of this, I thought were completely faulty. The whole concept that 'Oh, we just take these innocent young kids and put them in this evil environment and suddenly they do these evil things.' That's been the narrative for 50 years, and it's BS."

Perhaps the most valuable thing to come out of the documentary project was the re-enactment, which reunited the original participants for the first time in 50 years. They were able to rehash their experiences, mend some fences, and interact with the actors playing them. Eshleman even apologized to Ramsay during the reunion for his actions during the experiment. "I sincerely meant that," he said. "I would feel terrible if anybody actually suffered any damage as a result of this big play acting that we did. I wasn't aware of it at the time."

"All of us were manipulated to an extreme but in really different ways; that's why it was all so dramatic," said Ramsay. "So the things that we ascribed to each other in the experience, it's all entangled. You can't say that any one person did this. I do think that Zimbardo was wrong. There's always an underlying moral possibility that you could always choose to do something different the next day. You can act better tomorrow."

The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth is now streaming on Disney+.

- 2. Horrifying medical device malfunction: Abdominal implant erupts from leg

- 3. As NASA increasingly relies on commercial space, there are some troubling signs

- 4. Google stops letting sites like Forbes rule search for “Best CBD Gummies“

- 5. The key moment came 38 minutes after Starship roared off the launch pad

Unchaining the Stanford Prison Experiment: Philip Zimbardo’s famous study falls under scrutiny

On March 7, 2007, Philip Zimbardo used his last lecture at Stanford to declare that he’d left his most famous experiment behind.

Capping off a discussion of the 1971 findings that made him a public figure, movie character and textbook staple, the renowned psychology professor told the audience he was ready to start probing acts of heroism, rather than acts of abuse.

“I’m never going to study evil again,” he said.

The room was packed – not unusual for a course featuring Zimbardo, whose six-day Stanford Prison Experiment drew great attention as a dramatic demonstration of the power of roles and the way ordinary people can turn cruel under the wrong circumstances. Students who frequented the psychology department in Jordan Hall might have noticed a plaque marking the site of the study: Nearly 40 years prior, the building’s basement hosted a mock jail of college students in which – as Zimbardo tells it – student guards went so rogue with power and prisoners became so depressed that the professor had to call off his experiment. A colleague gushed later that week to Stanford News that Zimbardo’s research and teaching contributions were “probably unmatched by anyone – not only at Stanford, but throughout the world.”

Despite that switch to heroism he announced in his farewell lecture, Zimbardo remains inextricably linked to his most controversial work, conducted when he was in his 30s and newly tenured at Stanford. Now, though, Zimbardo battles accusations of questionable methodology and scientific fraud.

A journalist’s revisiting of the prison experiment has cast new doubt on its value: In an article quickly picked up around web, Ben Blum highlights participants’ claims that they were just acting and archival footage that he presents as evidence Zimbardo and his collaborators worked to elicit particular behavior. A French book by author Thibault Le Texier, published two months before Blum’s article, catalogues even more criticisms. While the summer’s discussion of the Stanford Prison Experiment focused on Blum’s arguments, an English-language summary of Le Texier’s findings – slated to publish in American Psychologist this month – could set off even greater scrutiny of the study as it reaches a U.S. audience.

The ensuing debate is rocking 85-year-old Zimbardo’s legacy in a way that decades of long-simmering but quiet critiques of the study didn’t, reshaping the experiment’s public image amid growing skepticism of influential psychology studies. Those who questioned the experiment for years are wondering why the reckoning took so long.

Others find value in the study despite its criticisms – and wonder if some of the blaring headlines sparked by Blum’s article, which asserts that “The most famous psychology study of all time was a sham” suffer from the same lack of nuance that characterized earlier coverage of the prison experiment.

Caught in the center, even Zimbardo seems torn between describing the experiment as an elaborate show and touting its scientific value. This comes across when he responds to the account of James Peterson M.S. ’91 Ph.D. ’74, a prisoner in the study who says he was let go early for no apparent reason.

Peterson, then a Ph.D. in engineering, recalls doing “a really lousy job as a guard” – nerdy and socially awkward, he drew weird looks during a count-off of the prisoners’ numbers by whimsically ordering the other students to yell out their ID numbers in “nines complement,” a computer science term.

Peterson has a hunch that his silly performance got him kicked out of the experiment. After his shift finished, he claims that someone on the research team – he doesn’t remember who – called him over to say he didn’t have to return. It turned out he wasn’t needed anymore, Peterson said.

Faced with this story, Zimbardo said he doesn’t remember Peterson but didn’t attempt to contradict Peterson’s account. Instead, he explained that “it might have been that Peterson just didn’t want to get into the role. That is, you know, just didn’t want to force the prisoners to do push-ups and jumping jacks and all the other things.”

“The only reason we would let a guard go,” he said, “is if he was not playing his role.” Zimbardo doesn’t seem to see an issue with removing someone from the experiment for failing to display the role-conforming behavior the researchers were observing for.

“The point is, it’s a drama,” he says. “You have to play the role in order for the whole thing to work.”

‘Nobody read it’

Siamak Movahedi, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston who specializes in social psychology, was one of the Stanford Prison Experiment’s earliest doubters. In 1975, just a few years after the study made headlines, Movahedi and his colleague Ali Banuazizi published the first major methodological critique of the experiment in American Psychologist.

The two scholars argued that the Stanford Prison Experiment did not show students genuinely consumed by their roles as prisoner and guard. Rather, they said, it showed participants engaging in a sort of theater – acting out stereotypical guard and prisoner behavior in response to what psychologists call “demand characteristics,” or cues on the goals of an experiment that participants pick up on. Movahedi and Banuazizi are skeptical of the idea that a bunch of white college students roleplaying for a week could reproduce the psychological workings of a real prison.

Their paper went largely unnoticed until just recently, when Movahedi started to notice surprising readership statistics from sites like academia.com – where, in August, the paper was downloaded at least 400 times.

“For 40 years, nobody read it,” Movahedi said.

The sudden interest raises a question for many of Zimbardo’s critics in the psychology community: What took so long? You don’t have to read Ben Blum’s article, they say, to realize that Zimbardo’s project was flawed in an experimental sense.

And yet, Movahedi’s issue is with Zimbardo’s approach, not his message about the power of the situation. Several decades ago, a San Francisco attorney called Movahedi looking for criticism of the prison experiment’s findings; Zimbardo was set to testify in a case about prison abuse, and the lawyer wanted Movahedi to speak against him. Movahedi promptly called Zimbardo and offered to write him a note of qualified support.

“I sent him a letter saying we simply have some disagreements with you on methodological issues; however, we completely share your conclusion and hypotheses that it’s the structure which leads to some of this oppressive behavior,” Movahedi recalled.

Movahedi understands why the prison study has stuck around. For one thing, it’s a hit with students. It’s a good teaching tool that gets their attention and pushes them to consider roles and social structure. Movahedi presents it in his classes every October, albeit with a discussion of its shortcomings.

He calls the prison study an “evocative object,” something useful for thinking but not for real data on a research question.

“It’s kind of a little play-acting that makes a point,” he said.

Although Zimbardo calls his study a “drama,” he views it as more than mere theater. He presents it as research from one of the top psychology departments in the country, as evidence for legal cases and debates over U.S. policy . He’s spoken before Congress. He’s called for prison reform. He testified for the defense in the Abu Ghraib guard trials, saying that situational forces just like those in the Stanford Prison Experiment led a good guy to abuse detainees.

Movahedi’s coauthor Banuazizi said he’s disappointed that Zimbardo chose to ignore the criticisms and continue pushing a “glorified” narrative of the experiment.

“In doing so, I believe, he did a disservice to his own reputation and, more importantly, to the field of social psychology,” Banuazizi said.

Zimbardo responds