- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How the Experimental Method Works in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amanda Tust is an editor, fact-checker, and writer with a Master of Science in Journalism from Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Amanda-Tust-1000-ffe096be0137462fbfba1f0759e07eb9.jpg)

sturti/Getty Images

The Experimental Process

Types of experiments, potential pitfalls of the experimental method.

The experimental method is a type of research procedure that involves manipulating variables to determine if there is a cause-and-effect relationship. The results obtained through the experimental method are useful but do not prove with 100% certainty that a singular cause always creates a specific effect. Instead, they show the probability that a cause will or will not lead to a particular effect.

At a Glance

While there are many different research techniques available, the experimental method allows researchers to look at cause-and-effect relationships. Using the experimental method, researchers randomly assign participants to a control or experimental group and manipulate levels of an independent variable. If changes in the independent variable lead to changes in the dependent variable, it indicates there is likely a causal relationship between them.

What Is the Experimental Method in Psychology?

The experimental method involves manipulating one variable to determine if this causes changes in another variable. This method relies on controlled research methods and random assignment of study subjects to test a hypothesis.

For example, researchers may want to learn how different visual patterns may impact our perception. Or they might wonder whether certain actions can improve memory . Experiments are conducted on many behavioral topics, including:

The scientific method forms the basis of the experimental method. This is a process used to determine the relationship between two variables—in this case, to explain human behavior .

Positivism is also important in the experimental method. It refers to factual knowledge that is obtained through observation, which is considered to be trustworthy.

When using the experimental method, researchers first identify and define key variables. Then they formulate a hypothesis, manipulate the variables, and collect data on the results. Unrelated or irrelevant variables are carefully controlled to minimize the potential impact on the experiment outcome.

History of the Experimental Method

The idea of using experiments to better understand human psychology began toward the end of the nineteenth century. Wilhelm Wundt established the first formal laboratory in 1879.

Wundt is often called the father of experimental psychology. He believed that experiments could help explain how psychology works, and used this approach to study consciousness .

Wundt coined the term "physiological psychology." This is a hybrid of physiology and psychology, or how the body affects the brain.

Other early contributors to the development and evolution of experimental psychology as we know it today include:

- Gustav Fechner (1801-1887), who helped develop procedures for measuring sensations according to the size of the stimulus

- Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894), who analyzed philosophical assumptions through research in an attempt to arrive at scientific conclusions

- Franz Brentano (1838-1917), who called for a combination of first-person and third-person research methods when studying psychology

- Georg Elias Müller (1850-1934), who performed an early experiment on attitude which involved the sensory discrimination of weights and revealed how anticipation can affect this discrimination

Key Terms to Know

To understand how the experimental method works, it is important to know some key terms.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the effect that the experimenter is measuring. If a researcher was investigating how sleep influences test scores, for example, the test scores would be the dependent variable.

Independent Variable

The independent variable is the variable that the experimenter manipulates. In the previous example, the amount of sleep an individual gets would be the independent variable.

A hypothesis is a tentative statement or a guess about the possible relationship between two or more variables. In looking at how sleep influences test scores, the researcher might hypothesize that people who get more sleep will perform better on a math test the following day. The purpose of the experiment, then, is to either support or reject this hypothesis.

Operational definitions are necessary when performing an experiment. When we say that something is an independent or dependent variable, we must have a very clear and specific definition of the meaning and scope of that variable.

Extraneous Variables

Extraneous variables are other variables that may also affect the outcome of an experiment. Types of extraneous variables include participant variables, situational variables, demand characteristics, and experimenter effects. In some cases, researchers can take steps to control for extraneous variables.

Demand Characteristics

Demand characteristics are subtle hints that indicate what an experimenter is hoping to find in a psychology experiment. This can sometimes cause participants to alter their behavior, which can affect the results of the experiment.

Intervening Variables

Intervening variables are factors that can affect the relationship between two other variables.

Confounding Variables

Confounding variables are variables that can affect the dependent variable, but that experimenters cannot control for. Confounding variables can make it difficult to determine if the effect was due to changes in the independent variable or if the confounding variable may have played a role.

Psychologists, like other scientists, use the scientific method when conducting an experiment. The scientific method is a set of procedures and principles that guide how scientists develop research questions, collect data, and come to conclusions.

The five basic steps of the experimental process are:

- Identifying a problem to study

- Devising the research protocol

- Conducting the experiment

- Analyzing the data collected

- Sharing the findings (usually in writing or via presentation)

Most psychology students are expected to use the experimental method at some point in their academic careers. Learning how to conduct an experiment is important to understanding how psychologists prove and disprove theories in this field.

There are a few different types of experiments that researchers might use when studying psychology. Each has pros and cons depending on the participants being studied, the hypothesis, and the resources available to conduct the research.

Lab Experiments

Lab experiments are common in psychology because they allow experimenters more control over the variables. These experiments can also be easier for other researchers to replicate. The drawback of this research type is that what takes place in a lab is not always what takes place in the real world.

Field Experiments

Sometimes researchers opt to conduct their experiments in the field. For example, a social psychologist interested in researching prosocial behavior might have a person pretend to faint and observe how long it takes onlookers to respond.

This type of experiment can be a great way to see behavioral responses in realistic settings. But it is more difficult for researchers to control the many variables existing in these settings that could potentially influence the experiment's results.

Quasi-Experiments

While lab experiments are known as true experiments, researchers can also utilize a quasi-experiment. Quasi-experiments are often referred to as natural experiments because the researchers do not have true control over the independent variable.

A researcher looking at personality differences and birth order, for example, is not able to manipulate the independent variable in the situation (personality traits). Participants also cannot be randomly assigned because they naturally fall into pre-existing groups based on their birth order.

So why would a researcher use a quasi-experiment? This is a good choice in situations where scientists are interested in studying phenomena in natural, real-world settings. It's also beneficial if there are limits on research funds or time.

Field experiments can be either quasi-experiments or true experiments.

Examples of the Experimental Method in Use

The experimental method can provide insight into human thoughts and behaviors, Researchers use experiments to study many aspects of psychology.

A 2019 study investigated whether splitting attention between electronic devices and classroom lectures had an effect on college students' learning abilities. It found that dividing attention between these two mediums did not affect lecture comprehension. However, it did impact long-term retention of the lecture information, which affected students' exam performance.

An experiment used participants' eye movements and electroencephalogram (EEG) data to better understand cognitive processing differences between experts and novices. It found that experts had higher power in their theta brain waves than novices, suggesting that they also had a higher cognitive load.

A study looked at whether chatting online with a computer via a chatbot changed the positive effects of emotional disclosure often received when talking with an actual human. It found that the effects were the same in both cases.

One experimental study evaluated whether exercise timing impacts information recall. It found that engaging in exercise prior to performing a memory task helped improve participants' short-term memory abilities.

Sometimes researchers use the experimental method to get a bigger-picture view of psychological behaviors and impacts. For example, one 2018 study examined several lab experiments to learn more about the impact of various environmental factors on building occupant perceptions.

A 2020 study set out to determine the role that sensation-seeking plays in political violence. This research found that sensation-seeking individuals have a higher propensity for engaging in political violence. It also found that providing access to a more peaceful, yet still exciting political group helps reduce this effect.

While the experimental method can be a valuable tool for learning more about psychology and its impacts, it also comes with a few pitfalls.

Experiments may produce artificial results, which are difficult to apply to real-world situations. Similarly, researcher bias can impact the data collected. Results may not be able to be reproduced, meaning the results have low reliability .

Since humans are unpredictable and their behavior can be subjective, it can be hard to measure responses in an experiment. In addition, political pressure may alter the results. The subjects may not be a good representation of the population, or groups used may not be comparable.

And finally, since researchers are human too, results may be degraded due to human error.

What This Means For You

Every psychological research method has its pros and cons. The experimental method can help establish cause and effect, and it's also beneficial when research funds are limited or time is of the essence.

At the same time, it's essential to be aware of this method's pitfalls, such as how biases can affect the results or the potential for low reliability. Keeping these in mind can help you review and assess research studies more accurately, giving you a better idea of whether the results can be trusted or have limitations.

Colorado State University. Experimental and quasi-experimental research .

American Psychological Association. Experimental psychology studies human and animals .

Mayrhofer R, Kuhbandner C, Lindner C. The practice of experimental psychology: An inevitably postmodern endeavor . Front Psychol . 2021;11:612805. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.612805

Mandler G. A History of Modern Experimental Psychology .

Stanford University. Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt . Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Britannica. Gustav Fechner .

Britannica. Hermann von Helmholtz .

Meyer A, Hackert B, Weger U. Franz Brentano and the beginning of experimental psychology: implications for the study of psychological phenomena today . Psychol Res . 2018;82:245-254. doi:10.1007/s00426-016-0825-7

Britannica. Georg Elias Müller .

McCambridge J, de Bruin M, Witton J. The effects of demand characteristics on research participant behaviours in non-laboratory settings: A systematic review . PLoS ONE . 2012;7(6):e39116. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039116

Laboratory experiments . In: The Sage Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Allen M, ed. SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781483381411.n287

Schweizer M, Braun B, Milstone A. Research methods in healthcare epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship — quasi-experimental designs . Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 2016;37(10):1135-1140. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.117

Glass A, Kang M. Dividing attention in the classroom reduces exam performance . Educ Psychol . 2019;39(3):395-408. doi:10.1080/01443410.2018.1489046

Keskin M, Ooms K, Dogru AO, De Maeyer P. Exploring the cognitive load of expert and novice map users using EEG and eye tracking . ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf . 2020;9(7):429. doi:10.3390.ijgi9070429

Ho A, Hancock J, Miner A. Psychological, relational, and emotional effects of self-disclosure after conversations with a chatbot . J Commun . 2018;68(4):712-733. doi:10.1093/joc/jqy026

Haynes IV J, Frith E, Sng E, Loprinzi P. Experimental effects of acute exercise on episodic memory function: Considerations for the timing of exercise . Psychol Rep . 2018;122(5):1744-1754. doi:10.1177/0033294118786688

Torresin S, Pernigotto G, Cappelletti F, Gasparella A. Combined effects of environmental factors on human perception and objective performance: A review of experimental laboratory works . Indoor Air . 2018;28(4):525-538. doi:10.1111/ina.12457

Schumpe BM, Belanger JJ, Moyano M, Nisa CF. The role of sensation seeking in political violence: An extension of the significance quest theory . J Personal Social Psychol . 2020;118(4):743-761. doi:10.1037/pspp0000223

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- General Categories

- Mental Health

- IQ and Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

Experimental Method in Psychology: Principles, Applications, and Limitations

As the cornerstone of psychological research, the experimental method has revolutionized our understanding of the human mind, behavior, and the intricate workings of the brain. This powerful approach has paved the way for countless breakthroughs in our quest to unravel the mysteries of human cognition and behavior. From the early days of Wilhelm Wundt’s pioneering work to the cutting-edge neuroscience experiments of today, the experimental method has been the driving force behind our ever-expanding knowledge of psychology.

But what exactly is the experimental method, and why is it so crucial to psychological research? Let’s dive into the fascinating world of experimental psychology and explore its principles, applications, and limitations.

The Birth of Experimental Psychology: A Journey Through Time

Picture this: It’s the late 19th century, and psychology is still in its infancy. Enter Wilhelm Wundt, a German physiologist with a burning curiosity about the human mind. In 1879, Wundt established the first psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig, marking the birth of experimental psychology as we know it today.

Wundt’s groundbreaking work laid the foundation for a more scientific approach to studying the mind. He believed that mental processes could be measured and analyzed systematically, just like physical phenomena. This radical idea sparked a revolution in psychological research, inspiring generations of scientists to explore the depths of human cognition and behavior through carefully controlled experiments.

As the field of psychology evolved, so did the experimental method. Researchers refined their techniques, developed new tools, and tackled increasingly complex questions about the human mind. Today, laboratory experiments in psychology are sophisticated endeavors that employ cutting-edge technology and rigorous methodologies to unveil the science of human behavior.

The Building Blocks of Experimental Design: A Recipe for Scientific Discovery

At its core, the experimental method in psychology is all about uncovering cause-and-effect relationships. But how do researchers go about designing experiments that can reliably answer their questions? Let’s break down the key components of an experiment in psychology :

1. Variables: The stars of the show in any experiment are the variables. These are the factors that researchers manipulate or measure to test their hypotheses. There are three main types of variables:

– Independent variables: These are the factors that researchers deliberately manipulate to observe their effects on behavior or cognition. – Dependent variables: These are the outcomes or behaviors that researchers measure in response to changes in the independent variables. – Control variables: These are factors that researchers keep constant to ensure that they don’t interfere with the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

2. Hypothesis: Every good experiment starts with a clear, testable prediction about the relationship between variables. This hypothesis serves as the guiding light for the entire research process.

3. Experimental design: Researchers must carefully plan how they’ll manipulate variables, assign participants to groups, and collect data. This step is crucial for ensuring that the experiment can reliably answer the research question.

4. Participants: The people (or animals) who take part in the experiment are the lifeblood of psychological research. Careful selection and assignment of participants help ensure that the results are generalizable to the broader population.

5. Procedure: This is the step-by-step plan for conducting the experiment, including instructions for participants, data collection methods, and any necessary equipment or materials.

6. Data analysis: Once the experiment is complete, researchers use statistical techniques to make sense of their findings and determine whether their hypothesis was supported.

By carefully considering each of these components, researchers can design experiments that shed light on the complexities of human behavior and cognition.

The Art and Science of Experimental Design: Crafting the Perfect Study

Designing a psychological experiment is both an art and a science. It requires creativity, critical thinking, and a deep understanding of scientific principles. Let’s explore some of the key considerations that researchers must keep in mind when designing their studies:

1. Establishing cause-and-effect relationships: The holy grail of experimental psychology is uncovering causal relationships between variables. To do this, researchers must carefully manipulate independent variables while controlling for potential confounds.

2. Controlling for confounding variables: In the messy world of human behavior, countless factors can influence our thoughts and actions. Researchers must be vigilant in identifying and controlling for these potential confounds to ensure that their results are valid.

3. Randomization: This powerful technique helps reduce bias by ensuring that participants have an equal chance of being assigned to different experimental conditions. It’s like shuffling a deck of cards before dealing – it helps level the playing field.

4. Types of experimental designs: Researchers can choose from various experimental designs, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The two main categories are:

– Between-subjects designs: Different groups of participants are exposed to different conditions. – Within-subjects designs: The same participants are exposed to multiple conditions.

The choice of design depends on the research question, practical considerations, and the nature of the variables being studied.

From Hypothesis to Discovery: The Journey of a Psychological Experiment

Now that we’ve explored the building blocks of experimental design, let’s walk through the steps of conducting a psychological experiment. It’s a journey filled with excitement, challenges, and the potential for groundbreaking discoveries.

1. Formulating a research question and hypothesis: Every great experiment starts with curiosity. Researchers identify a gap in our understanding of human behavior or cognition and develop a specific, testable hypothesis to address it.

2. Designing the experimental procedure: This is where the rubber meets the road. Researchers must carefully plan every aspect of their study, from the precise wording of instructions to the timing of each task.

3. Selecting and assigning participants: Finding the right participants is crucial for ensuring that the results are meaningful and generalizable. Researchers must consider factors like sample size, demographic characteristics, and recruitment methods.

4. Collecting and analyzing data: With everything in place, it’s time to run the experiment and gather data. This process can range from simple pencil-and-paper surveys to complex neuroimaging studies.

5. Drawing conclusions and reporting results: Once the data is collected, researchers use statistical analyses to determine whether their hypothesis was supported. They then interpret their findings in the context of existing theories and previous research.

This journey from hypothesis to discovery is at the heart of scientific progress in psychology. Each experiment, no matter how small, contributes to our growing understanding of the human mind and behavior.

Experiments in Action: Exploring the Diverse Landscape of Psychological Research

The experimental method is a versatile tool that can be applied to a wide range of psychological phenomena. Let’s take a whirlwind tour of some fascinating experiments across different areas of psychology:

1. Cognitive psychology: Researchers in this field use experiments to explore mental processes like memory, attention, and decision-making. For example, the famous “cocktail party effect” experiments revealed our remarkable ability to focus on a single conversation in a noisy room.

2. Social psychology: Experiments in this area shed light on how our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by others. The classic Milgram obedience experiments, while ethically controversial, revealed startling insights into human compliance with authority.

3. Developmental psychology: Researchers use clever experimental designs to study how children’s minds grow and change over time. Jean Piaget’s conservation tasks, for instance, revealed fascinating insights into children’s understanding of quantity and volume.

4. Clinical psychology: Experiments in this field help us understand mental health disorders and develop effective treatments. For example, studies on exposure therapy have shown its effectiveness in treating phobias and anxiety disorders.

5. Neuroscience and behavioral experiments: By combining behavioral tasks with brain imaging techniques, researchers can explore the neural basis of psychological phenomena. The famous “split-brain” experiments, for instance, revealed fascinating insights into how the two hemispheres of the brain work together.

These examples barely scratch the surface of the diverse and exciting world of psychological experiments. Each study contributes to our growing understanding of the human mind and behavior, piece by piece.

The Power and Promise of Experimental Psychology

The experimental method has numerous advantages that make it a cornerstone of psychological research:

1. High internal validity: By carefully controlling variables, experiments allow researchers to draw strong conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships.

2. Ability to establish causality: This is perhaps the most significant advantage of experiments. They allow us to move beyond mere correlation and identify true causal relationships.

3. Replicability and generalizability: Well-designed experiments can be replicated by other researchers, helping to confirm and extend findings. This is crucial for building a solid foundation of scientific knowledge.

4. Precision in measuring variables: Experiments allow for precise manipulation and measurement of variables, leading to more accurate and reliable results.

5. Contribution to theory development and testing: Experiments play a crucial role in testing and refining psychological theories, driving the field forward.

The experimental effects in psychology have had a profound impact on our understanding of human behavior and cognition. From uncovering the basic principles of learning and memory to revealing the complexities of social influence, experiments have been at the forefront of psychological discovery.

Navigating the Challenges: Limitations and Ethical Considerations

While the experimental method is incredibly powerful, it’s not without its limitations and ethical challenges. As researchers, we must be aware of these issues and work to address them:

1. Potential for artificial settings: Laboratory experiments may create environments that don’t accurately reflect real-world situations, potentially limiting the experimental realism in psychology .

2. Ethical concerns: Experiments involving human participants must adhere to strict ethical guidelines to protect participants’ well-being and rights. The infamous Stanford Prison Experiment serves as a cautionary tale about the potential for ethical breaches in psychological research.

3. Challenges in studying complex phenomena: Some aspects of human behavior and cognition are difficult to study in controlled laboratory settings, requiring researchers to be creative in their experimental designs.

4. Potential researcher bias and demand characteristics: Experimenters must be careful not to inadvertently influence participants’ behavior through subtle cues or expectations.

5. Time and resource constraints: Well-designed experiments can be time-consuming and expensive, potentially limiting the scope of research questions that can be addressed.

These disadvantages of experiments in psychology highlight the need for researchers to be thoughtful and creative in their approach to studying human behavior and cognition.

The Future of Experimental Psychology: Pushing the Boundaries of Discovery

As we look to the future, the experimental method in psychology continues to evolve and adapt to new challenges and opportunities. Emerging technologies, such as virtual reality and advanced brain imaging techniques, are opening up exciting new avenues for research.

Researchers are also working to address some of the limitations of traditional experiments by developing innovative methodologies. For example, ecological momentary assessment allows researchers to study behavior in real-world settings, bridging the gap between laboratory experiments and naturalistic observation.

The future of experimental psychology lies in striking a balance between rigorous scientific methodology and real-world applicability. By combining the strengths of experimental designs with other research approaches, psychologists can continue to push the boundaries of our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

In conclusion, the experimental method remains a powerful and indispensable tool in psychological research. From its humble beginnings in Wilhelm Wundt’s laboratory to the cutting-edge neuroscience experiments of today, this approach has revolutionized our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

As we continue to unravel the mysteries of human cognition and behavior, the experimental method will undoubtedly play a crucial role. By embracing new technologies, addressing ethical concerns, and pushing the boundaries of experimental design, researchers can ensure that this cornerstone of psychological research remains as relevant and impactful as ever.

So, the next time you hear about a fascinating psychological study, take a moment to appreciate the careful planning, creativity, and scientific rigor that went into its design. Who knows? Maybe you’ll be inspired to design your own experiment and contribute to our ever-growing understanding of the human mind.

References:

1. Coolican, H. (2018). Research methods and statistics in psychology. Routledge.

2. Goodwin, C. J., & Goodwin, K. A. (2016). Research in psychology: Methods and design. John Wiley & Sons.

3. Kantowitz, B. H., Roediger III, H. L., & Elmes, D. G. (2014). Experimental psychology. Cengage Learning.

4. Leary, M. R. (2011). Introduction to behavioral research methods. Pearson.

5. Martin, D. W. (2007). Doing psychology experiments. Cengage Learning.

6. Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

7. Shaughnessy, J. J., Zechmeister, E. B., & Zechmeister, J. S. (2015). Research methods in psychology. McGraw-Hill Education.

8. Smith, R. A., & Davis, S. F. (2012). The psychologist as detective: An introduction to conducting research in psychology. Pearson.

9. Stanovich, K. E. (2013). How to think straight about psychology. Pearson.

10. Weiten, W. (2016). Psychology: Themes and variations. Cengage Learning.

Was this article helpful?

Would you like to add any comments (optional), leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Resources

Brain Samples: Unlocking the Secrets of Neuroscience

Discover Psychology Impact Factor: Exploring the Journal’s Influence and Significance

Confidence Intervals in Psychology: Enhancing Statistical Interpretation and Research Validity

Control Condition in Psychology: Definition, Purpose, and Applications

Dependent Variables in Psychology: Definition, Examples, and Importance

Debriefing in Psychology: Definition, Purpose, and Techniques

Correlation in Psychology: Definition, Types, and Applications

Data Collection Methods in Psychology: Essential Techniques for Researchers

Histogram in Psychology: Definition, Applications, and Significance

Dimensional vs Categorical Approach in Psychology: Comparing Methods of Classification

Experimental Method

This section explores the experimental method, as part of research methods in psychology. The experimental method is a fundamental approach in psychology used to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables. In experiments, researchers manipulate an independent variable (IV) to observe its effect on a dependent variable (DV) while controlling other potential influences. There are several types of experiments, including laboratory experiments, field experiments, natural experiments, and quasi-experiments. Each type has unique strengths and limitations, and they differ in terms of control, environment, and the extent to which variables can be manipulated.

Laboratory Experiments

Laboratory experiments take place in a highly controlled environment, often in a research lab. Researchers manipulate the IV and measure its effect on the DV while controlling for extraneous variables, which allows for greater precision and reliability.

Characteristics

- Conducted in a controlled, artificial environment.

- High level of control over variables.

- Participants are aware that they are in an experiment, although they may not know its purpose.

- High Control: Extraneous variables are minimised, making it easier to establish a causal relationship between the IV and DV.

- Reliability: The controlled setting and use of standardised procedures make it easier to replicate the study, enhancing reliability.

- Precision in Measurement: Laboratory equipment and controlled conditions allow for precise and accurate data collection.

Limitations

- Low Ecological Validity: The artificial setting may not reflect real-life situations, which limits generalisability to everyday behaviour.

- Demand Characteristics: Participants may guess the aim of the study and alter their behaviour accordingly, which can affect the results.

- Ethical Concerns: The controlled environment may require deception to prevent participants from changing their behaviour, raising ethical issues.

Milgram’s obedience study (1963) is a well-known laboratory experiment where participants were instructed to administer electric shocks to another person. The highly controlled setting allowed Milgram to investigate obedience, though ethical concerns arose due to deception and participant distress.

Field Experiments

Field experiments are conducted in natural, real-world settings rather than in a laboratory. Researchers still manipulate the IV, but the environment is more natural for participants, who may be unaware they are in a study.

- Conducted in real-world settings, such as schools, workplaces, or public spaces.

- Some control over the IV, but less control over extraneous variables compared to laboratory experiments.

- Participants may not be aware they are part of an experiment, which reduces demand characteristics.

- Higher Ecological Validity: Because field experiments occur in natural settings, the findings are more likely to be generalisable to real-world behaviour.

- Reduced Demand Characteristics: If participants are unaware of being observed, they are less likely to alter their behaviour, resulting in more genuine responses.

- Less Control: Extraneous variables are harder to control in a natural setting, which can lead to confounding variables and affect the validity of results.

- Ethical Issues: Informed consent and debriefing can be challenging if participants are unaware they are part of a study.

- Replication Difficulties: Due to the natural setting and uncontrollable variables, field experiments can be harder to replicate consistently.

Hofling et al. (1966) conducted a field experiment on obedience in a hospital setting, where nurses were instructed by a “doctor” to administer a potentially harmful dose of medication. The natural setting allowed researchers to observe real-world obedience, though informed consent was an issue.

Natural Experiments

Natural experiments are conducted when the researcher cannot manipulate the IV due to ethical or practical reasons; instead, the IV is naturally occurring. The researcher observes the effect of this naturally occurring variable on the DV without directly intervening.

- The IV occurs naturally, and researchers have no control over it.

- Often used to study events or circumstances that would be unethical or impossible to recreate in a lab (e.g., studying the effects of natural disasters on mental health).

- High in ecological validity as they often study real-world events.

- High Ecological Validity: Since natural experiments study real-world events, their findings are often generalisable to similar situations.

- Ethically Feasible: By not manipulating the IV, researchers can study situations that would otherwise be unethical to create, such as trauma from natural disasters.

- Unique Insight: Provides valuable data on situations that cannot be replicated in a lab setting.

- Lack of Control: Without control over the IV and extraneous variables, it is more challenging to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship.

- Replication Issues: Because the IV is naturally occurring, it may be difficult or impossible to replicate the experiment exactly.

- Causal Inference: The inability to control the IV limits the researcher’s ability to make firm causal conclusions.

Charlton et al. (2000) studied the impact of the introduction of television on children’s aggression in St. Helena. The natural introduction of television served as the IV, allowing researchers to observe its impact on behaviour without needing to manipulate the situation.

Quasi-Experiments

Quasi-experiments are similar to true experiments but lack full experimental control because participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions. Instead, groups are often based on existing characteristics, such as age, gender, or a medical condition.

- IV is based on pre-existing differences between participants (e.g., smokers vs. non-smokers).

- No random allocation to conditions; groups are formed based on natural differences.

- Often conducted in controlled environments to maximise internal validity.

- Practicality: Quasi-experiments enable the study of variables that cannot be manipulated for ethical or practical reasons, such as gender or mental health conditions.

- Ecological Validity: By studying naturally occurring groups, quasi-experiments provide insight into real-world differences and behaviours.

- Lack of Random Assignment: Without random allocation, there is a risk that pre-existing differences between groups could influence the results, potentially introducing confounding variables.

- Limited Causal Inference: It is challenging to establish cause and effect due to the lack of control over group allocation and potential extraneous variables.

- Ethical Issues in Some Cases: If working with vulnerable groups, researchers must ensure ethical considerations, such as informed consent and protection from harm, are upheld.

Baron-Cohen et al. (1997) used a quasi-experiment to study theory of mind in individuals with autism. The participants with autism could not be randomly assigned to the experimental group, as they already had the condition. This allowed researchers to study the cognitive differences associated with autism, but causal conclusions were limited.

Summary Table

The experimental method in psychology includes various types of experiments, each offering different strengths and limitations. Laboratory experiments provide high levels of control but may lack real-world applicability. Field experiments balance some control with higher ecological validity. Natural and quasi-experiments enable the study of variables that cannot be manipulated but present challenges in establishing causation. Together, these methods allow psychologists to investigate human behaviour across diverse contexts, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of psychological processes.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Experimental Method

Experimental method is a method in which a variable (independent variable that is hypothesized as a cause; IV) is manipulated by an experimenter and the corresponding change in another variable (dependent variable that is hypothesized as an effect; DV) is observed. To determine whether the change in the DV is caused by the IV, at least two groups are involved: a control group and an experimental group. The two groups are assumed to be identical in all respects except that the control group does not receive the treatment of the IV whereas the experimental group receives the treatment. In reality, no two groups are exactly identical. Therefore, to ensure both groups are identical except for the treatment or experimental manipulation of the IV, all participants are randomly assigned to either the control or experimental group(s). As a result, any innate differences between the members of the two groups are equally distributed.

As an example, consider a hypothetical study investigating the effect of violent TV programs on the behavior of children. The researcher first randomly assigns a group of children to either an experimental or control group, and then shows a violent TV program to children in the experimental group and a neutral program to children in the control group. After viewing their programs, the children are allowed to play in a room with other children and observed. As a result, children in the experimental condition may exhibit more aggressive behavior than children in the control group. Given the use of a control group and an experimental group, and the random assignment of children to each condition, the researcher may be able to infer that the violent TV program caused aggression among the children since they only differed in the type of program they watched.

Experimental methods facilitate making causal inferences easier. In a well-designed experiment, the relationship between the IV and DV is clear. The experimental method can isolate the relationship among variables, which occurs in a complex environment and is often unobservable. As in the example, the effect of violent TV programs is not easily observed in real settings. By controlling all of the other variables involved, a well-designed experiment makes it possible to discern the relationship between the IV(s) and DV(s). By doing so, experiments can provide grounds for further scientific investigation. In other situations, the relationship between any two variables is weak. Because experimenters can have a lot of control in an experiment, they may maximize the magnitude of the manipulation and thereby have higher power to detect the relationship. In these scenarios, the major concern of the experimenter is the existence of the relationship. Especially at an exploratory step, this kind of evidence may provide a clue as to whether further investigation is warranted.

The experimental method is not without its shortcomings. First of all, its major advantage can often be a disadvantage. An experimenter’s control over many aspects of the experiment often makes it hard to generalize the results to other situations. Therefore, the size of the effect in an experiment may not be observed in reality or in other studies. This is intensified because many variables are intertwined with other variables. In this sense, experiments are much simpler than reality. Experimenters may try to include more variables in the design to increase the generalizability of the results; however, often the inclusion of additional variables poses a challenge to experimenters. Experiments typically require more time and effort for each participant. This might be a part of the reason why experiments are not used to collect longitudinal data. Maintaining control over participants for long periods of time may cause ethical issues, and may even be impossible.

References:

- Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. (1991). Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approac Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Computer-assisted research design and analysis . Needham Heights, MA: Allyn &

- Trochim, W. (2002). Experimental design . Retrieved from http://trochim.human.cornell.edu/kb/desexper.htm

- Whitley, B. E., Jr. (1996). Principles of research in behavioral science. Mountain View, CA: Mayf

- Wolfe, L. M. (n.d.). Developmental research methods .

- Retrieved from http://www.webster.edu/~woolflm/methods/dehtml

What is experimental method in psychology?

What is the Experimental Method in Psychology?

The experimental method is a research design used in psychology to investigate hypotheses, experimentally testing a phenomenon or phenomenon, and drawing conclusions based on the results. This method is essential in psychology, as it allows researchers to systematically manipulate variables, control for extraneous factors, and draw causal conclusions about the relationship between variables.

Key Characteristics of Experimental Research

The following are key characteristics of experimental research:

- Experimental manipulation : Researchers manipulate the independent variable (IV) to test its effect on the dependent variable (DV).

- Controlled variables : Researchers control or manipulate variables that could affect the outcome of the study.

- Replication : Results are replicated to ensure the findings are reliable and generalizable.

Types of Experimental Designs

There are several types of experimental designs, including:

Advantages of Experimental Method

The experimental method offers several advantages, including:

- Control over extraneous variables : Researchers can better control for extraneous variables, reducing the influence of other factors on the outcome.

- Causality : Experimental research can establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

- High internal validity : Experimental research is considered to have high internal validity, as the results are based on data collected via the experimental design.

Limitations of Experimental Method

The experimental method is not without its limitations, including:

- High cost : Experimental research can be resource-intensive, requiring a significant amount of time, money, and personnel.

- Ethical concerns : Researchers must ensure that their experiment is ethically sound and does not cause harm to participants.

- External validity : Experimental research may have limited external validity, as the results may not generalize to real-world settings.

Real-World Example

The experimental method has been used in various areas of psychology, including:

- Social psychology : Researchers have used experimental designs to investigate social influence, persuasion, and attitude change.

- Cognitive psychology : Experimental research has been used to study attention, memory, and language processing.

- Clinical psychology : Experimental research has been used to develop and test therapies for various mental health conditions.

Applications of Experimental Method

The experimental method has a wide range of applications, including:

- Clinical research : Experimental research is used to develop and test new treatments, interventions, and therapies.

- Basic research : Experimental research is used to investigate fundamental psychological processes and mechanisms.

- Evaluating programs and policies : Experimental research is used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and policies.

In conclusion, the experimental method is a powerful tool in psychology, allowing researchers to investigate hypotheses, control for extraneous variables, and draw causal conclusions about the relationship between variables. While it has limitations, the experimental method has numerous advantages, including high internal validity and the ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships. As a result, the experimental method is widely used in various areas of psychology, including social psychology, cognitive psychology, and clinical psychology. By understanding the experimental method, researchers can design and implement studies that yield meaningful and generalizable results.

- How to charge your AirPods without the case?

- How to set up out of office in Google mail?

- How to see Snapchat chat history?

- When does Samsung Galaxy s4 come out?

- Is finch university real?

- How do You make a slideshow on iPhone?

- How do I secure my Internet connection?

- Why is it important to learn the scientific method?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Experimental Research

23 Experiment Basics

Learning objectives.

- Explain what an experiment is and recognize examples of studies that are experiments and studies that are not experiments.

- Distinguish between the manipulation of the independent variable and control of extraneous variables and explain the importance of each.

- Recognize examples of confounding variables and explain how they affect the internal validity of a study.

- Define what a control condition is, explain its purpose in research on treatment effectiveness, and describe some alternative types of control conditions.

What Is an Experiment?

As we saw earlier in the book, an experiment is a type of study designed specifically to answer the question of whether there is a causal relationship between two variables. In other words, whether changes in one variable (referred to as an independent variable ) cause a change in another variable (referred to as a dependent variable ). Experiments have two fundamental features. The first is that the researchers manipulate, or systematically vary, the level of the independent variable. The different levels of the independent variable are called conditions . For example, in Darley and Latané’s experiment, the independent variable was the number of witnesses that participants believed to be present. The researchers manipulated this independent variable by telling participants that there were either one, two, or five other students involved in the discussion, thereby creating three conditions. For a new researcher, it is easy to confuse these terms by believing there are three independent variables in this situation: one, two, or five students involved in the discussion, but there is actually only one independent variable (number of witnesses) with three different levels or conditions (one, two or five students). The second fundamental feature of an experiment is that the researcher exerts control over, or minimizes the variability in, variables other than the independent and dependent variable. These other variables are called extraneous variables . Darley and Latané tested all their participants in the same room, exposed them to the same emergency situation, and so on. They also randomly assigned their participants to conditions so that the three groups would be similar to each other to begin with. Notice that although the words manipulation and control have similar meanings in everyday language, researchers make a clear distinction between them. They manipulate the independent variable by systematically changing its levels and control other variables by holding them constant.

Manipulation of the Independent Variable

Again, to manipulate an independent variable means to change its level systematically so that different groups of participants are exposed to different levels of that variable, or the same group of participants is exposed to different levels at different times. For example, to see whether expressive writing affects people’s health, a researcher might instruct some participants to write about traumatic experiences and others to write about neutral experiences. The different levels of the independent variable are referred to as conditions , and researchers often give the conditions short descriptive names to make it easy to talk and write about them. In this case, the conditions might be called the “traumatic condition” and the “neutral condition.”

Notice that the manipulation of an independent variable must involve the active intervention of the researcher. Comparing groups of people who differ on the independent variable before the study begins is not the same as manipulating that variable. For example, a researcher who compares the health of people who already keep a journal with the health of people who do not keep a journal has not manipulated this variable and therefore has not conducted an experiment. This distinction is important because groups that already differ in one way at the beginning of a study are likely to differ in other ways too. For example, people who choose to keep journals might also be more conscientious, more introverted, or less stressed than people who do not. Therefore, any observed difference between the two groups in terms of their health might have been caused by whether or not they keep a journal, or it might have been caused by any of the other differences between people who do and do not keep journals. Thus the active manipulation of the independent variable is crucial for eliminating potential alternative explanations for the results.

Of course, there are many situations in which the independent variable cannot be manipulated for practical or ethical reasons and therefore an experiment is not possible. For example, whether or not people have a significant early illness experience cannot be manipulated, making it impossible to conduct an experiment on the effect of early illness experiences on the development of hypochondriasis. This caveat does not mean it is impossible to study the relationship between early illness experiences and hypochondriasis—only that it must be done using nonexperimental approaches. We will discuss this type of methodology in detail later in the book.

Independent variables can be manipulated to create two conditions and experiments involving a single independent variable with two conditions are often referred to as a single factor two-level design . However, sometimes greater insights can be gained by adding more conditions to an experiment. When an experiment has one independent variable that is manipulated to produce more than two conditions it is referred to as a single factor multi level design . So rather than comparing a condition in which there was one witness to a condition in which there were five witnesses (which would represent a single-factor two-level design), Darley and Latané’s experiment used a single factor multi-level design, by manipulating the independent variable to produce three conditions (a one witness, a two witnesses, and a five witnesses condition).

Control of Extraneous Variables

As we have seen previously in the chapter, an extraneous variable is anything that varies in the context of a study other than the independent and dependent variables. In an experiment on the effect of expressive writing on health, for example, extraneous variables would include participant variables (individual differences) such as their writing ability, their diet, and their gender. They would also include situational or task variables such as the time of day when participants write, whether they write by hand or on a computer, and the weather. Extraneous variables pose a problem because many of them are likely to have some effect on the dependent variable. For example, participants’ health will be affected by many things other than whether or not they engage in expressive writing. This influencing factor can make it difficult to separate the effect of the independent variable from the effects of the extraneous variables, which is why it is important to control extraneous variables by holding them constant.

Extraneous Variables as “Noise”

Extraneous variables make it difficult to detect the effect of the independent variable in two ways. One is by adding variability or “noise” to the data. Imagine a simple experiment on the effect of mood (happy vs. sad) on the number of happy childhood events people are able to recall. Participants are put into a negative or positive mood (by showing them a happy or sad video clip) and then asked to recall as many happy childhood events as they can. The two leftmost columns of Table 5.1 show what the data might look like if there were no extraneous variables and the number of happy childhood events participants recalled was affected only by their moods. Every participant in the happy mood condition recalled exactly four happy childhood events, and every participant in the sad mood condition recalled exactly three. The effect of mood here is quite obvious. In reality, however, the data would probably look more like those in the two rightmost columns of Table 5.1 . Even in the happy mood condition, some participants would recall fewer happy memories because they have fewer to draw on, use less effective recall strategies, or are less motivated. And even in the sad mood condition, some participants would recall more happy childhood memories because they have more happy memories to draw on, they use more effective recall strategies, or they are more motivated. Although the mean difference between the two groups is the same as in the idealized data, this difference is much less obvious in the context of the greater variability in the data. Thus one reason researchers try to control extraneous variables is so their data look more like the idealized data in Table 5.1 , which makes the effect of the independent variable easier to detect (although real data never look quite that good).

One way to control extraneous variables is to hold them constant. This technique can mean holding situation or task variables constant by testing all participants in the same location, giving them identical instructions, treating them in the same way, and so on. It can also mean holding participant variables constant. For example, many studies of language limit participants to right-handed people, who generally have their language areas isolated in their left cerebral hemispheres [1] . Left-handed people are more likely to have their language areas isolated in their right cerebral hemispheres or distributed across both hemispheres, which can change the way they process language and thereby add noise to the data.

In principle, researchers can control extraneous variables by limiting participants to one very specific category of person, such as 20-year-old, heterosexual, female, right-handed psychology majors. The obvious downside to this approach is that it would lower the external validity of the study—in particular, the extent to which the results can be generalized beyond the people actually studied. For example, it might be unclear whether results obtained with a sample of younger lesbian women would apply to older gay men. In many situations, the advantages of a diverse sample (increased external validity) outweigh the reduction in noise achieved by a homogeneous one.

Extraneous Variables as Confounding Variables

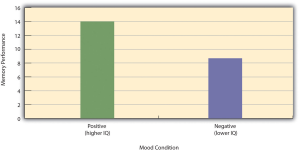

The second way that extraneous variables can make it difficult to detect the effect of the independent variable is by becoming confounding variables. A confounding variable is an extraneous variable that differs on average across levels of the independent variable (i.e., it is an extraneous variable that varies systematically with the independent variable). For example, in almost all experiments, participants’ intelligence quotients (IQs) will be an extraneous variable. But as long as there are participants with lower and higher IQs in each condition so that the average IQ is roughly equal across the conditions, then this variation is probably acceptable (and may even be desirable). What would be bad, however, would be for participants in one condition to have substantially lower IQs on average and participants in another condition to have substantially higher IQs on average. In this case, IQ would be a confounding variable.

To confound means to confuse , and this effect is exactly why confounding variables are undesirable. Because they differ systematically across conditions—just like the independent variable—they provide an alternative explanation for any observed difference in the dependent variable. Figure 5.1 shows the results of a hypothetical study, in which participants in a positive mood condition scored higher on a memory task than participants in a negative mood condition. But if IQ is a confounding variable—with participants in the positive mood condition having higher IQs on average than participants in the negative mood condition—then it is unclear whether it was the positive moods or the higher IQs that caused participants in the first condition to score higher. One way to avoid confounding variables is by holding extraneous variables constant. For example, one could prevent IQ from becoming a confounding variable by limiting participants only to those with IQs of exactly 100. But this approach is not always desirable for reasons we have already discussed. A second and much more general approach—random assignment to conditions—will be discussed in detail shortly.

Treatment and Control Conditions

In psychological research, a treatment is any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better. This intervention includes psychotherapies and medical treatments for psychological disorders but also interventions designed to improve learning, promote conservation, reduce prejudice, and so on. To determine whether a treatment works, participants are randomly assigned to either a treatment condition , in which they receive the treatment, or a control condition , in which they do not receive the treatment. If participants in the treatment condition end up better off than participants in the control condition—for example, they are less depressed, learn faster, conserve more, express less prejudice—then the researcher can conclude that the treatment works. In research on the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments, this type of experiment is often called a randomized clinical trial .

There are different types of control conditions. In a no-treatment control condition , participants receive no treatment whatsoever. One problem with this approach, however, is the existence of placebo effects. A placebo is a simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that should make it effective, and a placebo effect is a positive effect of such a treatment. Many folk remedies that seem to work—such as eating chicken soup for a cold or placing soap under the bed sheets to stop nighttime leg cramps—are probably nothing more than placebos. Although placebo effects are not well understood, they are probably driven primarily by people’s expectations that they will improve. Having the expectation to improve can result in reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, which can alter perceptions and even improve immune system functioning (Price, Finniss, & Benedetti, 2008) [2] .

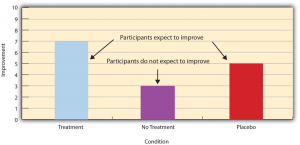

Placebo effects are interesting in their own right (see Note “The Powerful Placebo” ), but they also pose a serious problem for researchers who want to determine whether a treatment works. Figure 5.2 shows some hypothetical results in which participants in a treatment condition improved more on average than participants in a no-treatment control condition. If these conditions (the two leftmost bars in Figure 5.2 ) were the only conditions in this experiment, however, one could not conclude that the treatment worked. It could be instead that participants in the treatment group improved more because they expected to improve, while those in the no-treatment control condition did not.

Fortunately, there are several solutions to this problem. One is to include a placebo control condition , in which participants receive a placebo that looks much like the treatment but lacks the active ingredient or element thought to be responsible for the treatment’s effectiveness. When participants in a treatment condition take a pill, for example, then those in a placebo control condition would take an identical-looking pill that lacks the active ingredient in the treatment (a “sugar pill”). In research on psychotherapy effectiveness, the placebo might involve going to a psychotherapist and talking in an unstructured way about one’s problems. The idea is that if participants in both the treatment and the placebo control groups expect to improve, then any improvement in the treatment group over and above that in the placebo control group must have been caused by the treatment and not by participants’ expectations. This difference is what is shown by a comparison of the two outer bars in Figure 5.4 .

Of course, the principle of informed consent requires that participants be told that they will be assigned to either a treatment or a placebo control condition—even though they cannot be told which until the experiment ends. In many cases the participants who had been in the control condition are then offered an opportunity to have the real treatment. An alternative approach is to use a wait-list control condition , in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it. This disclosure allows researchers to compare participants who have received the treatment with participants who are not currently receiving it but who still expect to improve (eventually). A final solution to the problem of placebo effects is to leave out the control condition completely and compare any new treatment with the best available alternative treatment. For example, a new treatment for simple phobia could be compared with standard exposure therapy. Because participants in both conditions receive a treatment, their expectations about improvement should be similar. This approach also makes sense because once there is an effective treatment, the interesting question about a new treatment is not simply “Does it work?” but “Does it work better than what is already available?

The Powerful Placebo

Many people are not surprised that placebos can have a positive effect on disorders that seem fundamentally psychological, including depression, anxiety, and insomnia. However, placebos can also have a positive effect on disorders that most people think of as fundamentally physiological. These include asthma, ulcers, and warts (Shapiro & Shapiro, 1999) [3] . There is even evidence that placebo surgery—also called “sham surgery”—can be as effective as actual surgery.

Medical researcher J. Bruce Moseley and his colleagues conducted a study on the effectiveness of two arthroscopic surgery procedures for osteoarthritis of the knee (Moseley et al., 2002) [4] . The control participants in this study were prepped for surgery, received a tranquilizer, and even received three small incisions in their knees. But they did not receive the actual arthroscopic surgical procedure. Note that the IRB would have carefully considered the use of deception in this case and judged that the benefits of using it outweighed the risks and that there was no other way to answer the research question (about the effectiveness of a placebo procedure) without it. The surprising result was that all participants improved in terms of both knee pain and function, and the sham surgery group improved just as much as the treatment groups. According to the researchers, “This study provides strong evidence that arthroscopic lavage with or without débridement [the surgical procedures used] is not better than and appears to be equivalent to a placebo procedure in improving knee pain and self-reported function” (p. 85).

- Knecht, S., Dräger, B., Deppe, M., Bobe, L., Lohmann, H., Flöel, A., . . . Henningsen, H. (2000). Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 123 (12), 2512-2518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/123.12.2512 ↵

- Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: Recent advances and current thought. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 565–590. ↵

- Shapiro, A. K., & Shapiro, E. (1999). The powerful placebo: From ancient priest to modern physician . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↵

- Moseley, J. B., O’Malley, K., Petersen, N. J., Menke, T. J., Brody, B. A., Kuykendall, D. H., … Wray, N. P. (2002). A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347 , 81–88. ↵

A type of study designed specifically to answer the question of whether there is a causal relationship between two variables.

The variable the experimenter manipulates.

The variable the experimenter measures (it is the presumed effect).

The different levels of the independent variable to which participants are assigned.

Holding extraneous variables constant in order to separate the effect of the independent variable from the effect of the extraneous variables.

Any variable other than the dependent and independent variable.

Changing the level, or condition, of the independent variable systematically so that different groups of participants are exposed to different levels of that variable, or the same group of participants is exposed to different levels at different times.

An experiment design involving a single independent variable with two conditions.

When an experiment has one independent variable that is manipulated to produce more than two conditions.

An extraneous variable that varies systematically with the independent variable, and thus confuses the effect of the independent variable with the effect of the extraneous one.

Any intervention meant to change people’s behavior for the better.

The condition in which participants receive the treatment.

The condition in which participants do not receive the treatment.

An experiment that researches the effectiveness of psychotherapies and medical treatments.

The condition in which participants receive no treatment whatsoever.

A simulated treatment that lacks any active ingredient or element that is hypothesized to make the treatment effective, but is otherwise identical to the treatment.

An effect that is due to the placebo rather than the treatment.

Condition in which the participants receive a placebo rather than the treatment.

Condition in which participants are told that they will receive the treatment but must wait until the participants in the treatment condition have already received it.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO