Select Page

A ‘View Of Judaism in its Own Terms

Some historical reflections on Jewish Studies at HDS.

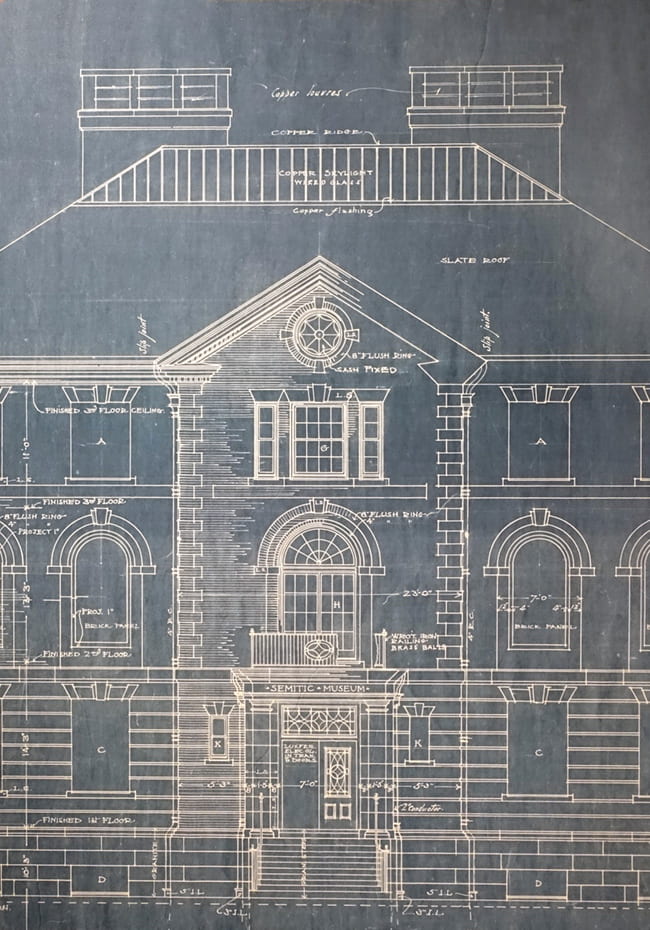

Blueprint for the Harvard Semitic Museum

Narrating Judaism Autumn/Winter 2018

By John Levenson

In one sense, Jewish Studies was central to Harvard College from its inception.

The ethos in which the institution was founded was that of Christian Hebraism in general and its English Protestant version in particular. Oxford and Cambridge had both instituted Regius Professorships of Hebrew as early as the 1540s. But Harvard went further, making the study of Hebrew a requirement of the undergraduate program—the only program it had, of course, until late in the eighteenth century. It is worth noting that, in line with the general character of Protestant Hebraism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Hebraic and Judaic interests of these Protestant intellectuals were not limited to the Hebrew Bible, or, as their tradition understood that collection, the Old Testament. 1 (The difference is more than terminological.) Speaking of John Harvard’s bequest, a commencement orator around 1670 offered that Mr. Harvard, by endowing a college rather than a church, “followed Maimonides in considering the school superior to and more sacred than the synagogue.” Maimonides, of course, is the great philosopher, law codifier, and Jewish communal leader of the twelfth century. Here, the reference is to his codification of the halakhah (normative Talmudic law) that a synagogue can be made into a school for the study of Torah but not the reverse. 2 Unfortunately, that involvement in the full range of post-biblical Hebraica has not always characterized Old Testament scholars at Harvard.

In the eighteenth century, the dominant figure in Harvard Hebraic studies was Judah Monis, who was “the first instructor on the Harvard faculty who taught nothing but Hebrew,” and who also authored the first Hebrew textbook published in North America. 3 A European-trained Jewish scholar, Monis was required to convert to Christianity in order to assume his position on the faculty, which he occupied for nearly 40 years. At his baptism in Harvard Yard, he preached a sermon in which he sought to demonstrate that Jesus, and not the future figure of Jewish expectation, was the messiah 4 —given the occasion, a wise choice of subjects, if you ask me. The contrary thesis would surely have landed him in hotter water. Although doubts about Monis’s sincerity in converting have long been raised, 5 I am certain that he was absolutely sincere in his desire for a Harvard professorship.

In 1763, three years after Monis’s retirement, a bequest from the Boston merchant Thomas Hancock (uncle of John Hancock) established a professorship at Harvard, in the words of the will, “to profess and teach the Oriental Languages, especially the Hebrew, in said College.” The legislation that the College passed on June 12, 1765, specified that the Hancock Professor of Hebrew and other Oriental Languages in Harvard College should teach not only Hebrew and Chaldee (meaning Aramaic), but also Samaritan, Syriac (that is, Christian Aramaic), and Arabic. (I assume “Samaritan” here refers to the Hebrew of the Samaritan Pentateuch.) The legislation also specified that the incumbent “shall declare himself to be of the Protestant Reformed religion, as it is now professed and practiced by the churches in New England.” 6

“Great caution is necessary,” Spinoza wrote, “not to confuse the mind of the prophet or historian with the mind of the Holy Spirit and the truth of the matter.”

A large part of the enormous fortune the childless Thomas Hancock made, much of it reportedly through smuggling, 7 eventually went to his nephew, the famous patriot, whom he had raised since the latter was 13 and who, I’m sure, was happy to claim the legacy by putting his John Hancock on the appropriate forms. Hancock’s bequest, with its requirement that the incumbents shall profess the Protestant Reformed religion and do so in the New England manner, looked backward rather than forward. For only a generation later, the Unitarians would emerge triumphant in the College and soon thereafter, in 1816, found the Divinity School. And at the same time, the discipline of biblical studies was undergoing a massive shift. Under the impact of the Enlightenment, scholars, especially in Germany, began to separate the historical study of the scriptural literature from the religiously normative study of the same material. Baruch (or Benedict) de Spinoza, a late seventeenth-century forerunner of this movement, put the conceptual issue memorably. “Great caution is necessary,” Spinoza wrote, “not to confuse the mind of the prophet or historian with the mind of the Holy Spirit and the truth of the matter.” Now the focus should lie, again in Spinoza’s words, on “the life, the conduct, the studies of the author of each book, who he was, what was the occasion, and the epoch of his writing, whom did he write for, and in what language [and] the fate of each book.” 8 Precisely how these books, so interpreted, render the acts of God in the past, his will for the present, and his promises for the future is, to put it charitably, unclear. For Spinoza that was not a problem.

Hancock professors were fairly quick to shift to this new, historical-critical method. George Rapall Noyes, who held the chair from 1840 to 1868, was familiar with German scholarship and championed the new method. His successor, Edward James Young, Hancock Professor from 1869 to 1880, had devoted four years to study in Germany, one of them at Göttingen, where he was highly impressed with Heinrich Ewald, a pioneer of biblical criticism. 9

Young’s successor, Crawford Howell Toy, seems to have been a fascinating figure. A Southern Baptist who had served in the Confederate army and studied in Berlin after the war, Professor Toy broke with his denomination over his use of the critical method and become a Unitarian. 10 At Harvard, he broke new ground in developing in the College a Semitic Department, the forerunner of today’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. 11 To help him with this, he pushed for the appointment of his former pupil at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, David G. Lyon, who had received his doctorate in Assyriology from the University of Leipzig. Together, Toy and Lyon launched efforts to explore Mesopotamia in search of long-lost Babylonian and Assyrian materials, and out of those efforts there eventually emerged the Semitic Museum. The building itself was erected in 1903 through the generosity of the banker, businessman, and Jewish communal leader Jacob Schiff. The cost was $80,000. 12

With Lyon’s appointment—he eventually succeeded Toy in the Hancock chair—I think it is fair to say the emphasis in the study of the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament shifted to the ancient Near East and away from theology. This shift corresponded with a number of momentous changes in American society in general and at Harvard in particular—the emergence of the research university and the decline of the church-related college; the influx to America of large numbers of non-Protestant and non-British immigrants; the challenge the latter eventually posed to the Brahmin aristocracy; and, of course, the recovery of large numbers of ancient Near Eastern documents and the decipherments of their languages that had been taking place since the early nineteenth century. But it is important to remember as well that Lyon was a graduate of a theological seminary and held, sequentially, two chairs in the Divinity School. And note the first of the animating motives for the new Semitic Department that he explicitly listed: “To enable students intending to become ministers to complete in college the Hebrew requirement for the B.D. degree [i.e., bachelor of divinity, the ministerial degree], and thus gain more time later for subjects of strictly theological character.” 13

George Foot Moore (1851–1931) by Ignaz Marcel Gaugengigl. Harvard University Portrait Collection, gift of friends and colleagues of Dr. Moore to the Divinity School, 1926, h348, photo by Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Leaving aside more recent figures, the most impressive scholar of Hebraica in the history of Harvard is surely George Foot Moore (1851–1931), who served as Professor of the History of Religion from 1902 to 1928. And a remarkably capacious concept of religion he had: the first book of his two-volume History of Religions (1920) treated China, Japan, Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, India, Persia, Greece, and Rome, and the second focused on Judaism, Christianity, and Mohammedanism ( sic ). Even granting the obvious fact that far less was known about most of those traditions then than now and that the methodological and theoretical frameworks were more limited, one cannot come away from Moore’s study unimpressed with the command of historical and textual detail it exhibits and the author’s eagerness to be fair to the religions on which he wrote. In a memoir of Moore published soon after his death, his colleague (and sometime dean) William Wallace Fenn observed that “it was often said that he could have taught any course in the curriculum of the Theology School, except those listed under Practical Theology and Social Ethics, quite as satisfactorily as the professor who actually offered it.” 14 Personally, I am confident in the judgment that Fenn intended his comment to reflect on Moore rather than on his colleagues.

Moore came to his phenomenal Hebraic competence naturally. Fenn reports of his grandfather, the Reverend George Foot, that “largely by independent study, he mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and French” and that, having taught his daughter (Moore’s mother) Hebrew, the two of them had read the Hebrew Bible through in the original seven times before she was married. 15 Moore’s own formal education was strikingly short. Largely self-taught like his grandfather, he went into the pastorate after graduating Yale in two years and Union Theological Seminary in New York in one.

Into the pastorate but not out of scholarship. Serving a church in Zanesville, Ohio (1878–1883), he took up the study of rabbinic Hebrew with a local rabbi. His comments about the experience tell us much about both Moore himself and the type of study the two undertook:

It was an old-fashioned training. Its methods were doubtless of a kind which our pedagogical experts would regard as altogether obsolete; but it accomplished its end, which is, after all, the final test of the efficiency of a method. In one respect it differed widely from that of our schools; unsophisticated by educational psychology, the yeshiva-trained teacher, like his predecessors in the great age of classical learning in Western Europe, naively assumed that the object of studying a subject was to know it, not to acquire a certificate of having been through it. In that antiquated education the memory was systematically trained, not methodologically ruined. 16

Moore pursued Modern Hebrew at the same time, 17 something that to this day cannot be said of most scholars of the Hebrew Bible.

George Foot Moore became a leading figure in the scholarship of the Hebrew Bible, playing a major role in the importation of innovative German scholarship into the United States; his commentary on Judges (1895) is still considered a classic. 18

But it is primarily in the realm of rabbinic Judaism that he left his mark. His three-volume study, Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of the Tannaim (1927–1930), is an extraordinary accomplishment, though dated in important ways now. For our purposes, I would like instead to concentrate on “Christian Writers on Judaism,” a long essay that he published in Harvard Theological Review (of which he was a founding editor) in 1921. 19 For reasons we shall see, it remains highly instructive.

The opening sentence tells it all: “Christian interest in Jewish literature has always been apologetic or polemic rather than historical.” 20 Whereas in “early Christian apologetic . . . the controversial points were the interpretation and application of passages in the Old Testament” to Jesus, “the discussion in the Middle Ages . . . assumed a more learned character in the endeavor to demonstrate that Christian doctrines were supported by the authentic Jewish tradition . . . or by the mostly highly reputed Jewish interpreters.” 21 (About this, Moore, perhaps with an eye to scholarship in his own day, dryly remarks, “Whatever its value otherwise, it had at least one good result—it led to a much more zealous and assiduous study of Judaism than any purely scientific interest would have inspired.” 22 ) Later, in the age of the Reformation, Protestants endeavored to show “that on the issues in debate between Protestants and Catholics the Jews were on the Protestant side.” In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, however, “a broader interest in learning for its own sake as well as its uses prevailed . . . and led . . . to the creation of a great body of learned literature in every branch of Hebrew antiquities.” 23

In the case of the revival of Christian study of Judaism in the nineteenth century, Moore writes, “the actuating motive was to find in it the milieu of early Christianity” and, more ominously, “to exhibit the system of Palestinian Jewish theology in the first three or four centuries of our era as the antithesis of Christian theology and religion as they were taught in certain contemporary German schools.” 24 There thus emerged the notion that the Talmudic rabbis subscribed to an “abstract monotheism” by which they “exalted [God] out of this world, which, like an absentee proprietor, he administered henceforth by agents.” And thus there emerged as well the charge of “legalism,” which according to Moore, (writing, remember, in 1921) “for the last fifty years has become the very definition and the all-sufficient condemnation of Judaism.” Whereas before this, “Concretely Jewish observances are censured or ridiculed . . . ‘legalism’ as a system of religion, not to say as the essence of Judaism, no one seems to have discovered.” 25

Whatever it was that first impelled the young Moore to study with that rabbi in Zanesville, by the time he had become a mature scholar his research compelled him to recognize that the reflexive anti-Judaism of the Christian community was in urgent need of correction.

Moore’s own motivation was different. As one scholar puts it, “Moore did not attempt to establish connections between Judaism and Christianity, but”—and this was really quite revolutionary for a Christian scholar—“to present a composite and constructive view of Judaism in its own terms.” 26 Whatever it was that first impelled the young Moore to study with that rabbi in Zanesville, by the time he had become a mature scholar his research compelled him to recognize that the reflexive anti-Judaism of the Christian community was in urgent need of correction. As Fenn observes in his memoir, “Professor Moore . . . had come to believe that that popular conception of the Pharisees, although possibly true of some members of the sect, misrepresented them as a whole. He sometimes said to his friends: ‘If you and I had been living in Palestine in the first century of our era, we should have been Pharisees, I hope.’ ” 27

Although Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of the Tannaim remains an important compendium of rabbinic discussions, its assumptions are now, as mentioned, woefully out of date. For one thing, Moore failed to involve himself in sufficient depth in halakhah, or normative Jewish practice, the major focus of the Talmud and of much midrashic literature as well. 28 For another, he attributed a historically problematic normativity to rabbinic Judaism and failed to reckon with the vitality of its antecedents and competitors (although, in fairness, before the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, this was a more understandable move). He also accepted attributions of statements to various figures uncritically, thus limiting the utility of his massive study to historians. 29 Jacob Neusner was thus right when he wrote of Moore’s great study in 1980,“What is constructed is a static exercise in dogmatic theology.” 30 But Neusner erred when he observed in the same piece, “Moore closed many doors; he opened none.” 31 In fact, he opened the door to a fresh view of ancient Judaism for scores of Christian scholars—a “view of Judaism in its own terms.”

Not that every Christian scholar was willing to walk through it, as we shall see.

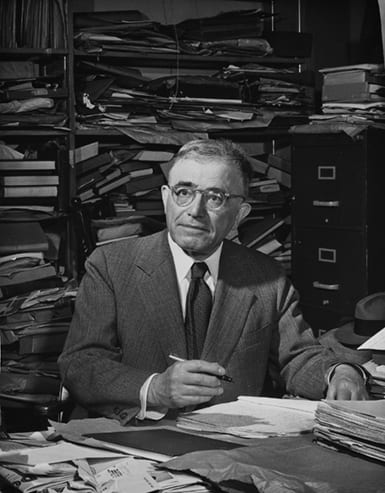

Harry Austryn Wolfson (1887–1974). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

The attentive reader will have noticed one element that has so far been missing in these reflections on Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School: Jews. Around 1912 this was to change, when Lyon and Moore spotted a brilliant young undergraduate who had immigrated with his family from Lithuania (then under czarist Russia), eventually creating a position for him and helping, along with Harvard Law professor (and later Supreme Court justice) Felix Frankfurter, to raise the money to fund it. 32 That young man, Harry Wolfson, was to serve on the Harvard faculty from 1915 to 1958. Although he remained grateful to the Divinity School—he had once lived in Divinity Hall—to the end of his career, and spoke warmly of the institution and of Moore in particular, 33 with his appointment the center of Jewish Studies at Harvard shifted to the Semitic Department, forerunner of today’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations (NELC).

The shift was, in a sense, inevitable. As Isadore Twersky, Wolfson’s disciple and successor as Nathan Littauer Professor of Hebrew Literature and Philosophy and the founding director of the Center for Jewish Studies, wrote in an appreciation of his teacher in 1976:

In the past—and that means up to very recent times—the study of Judaica was ancillary, secondary, fragmentary, or derivative. Jewish studies were sometimes referred to as service departments whose task was to help illumine an obscurity in Tacitus or Posidonius, a midrash in Jerome, a Hebrew allusion in Dante. . . . The establishment of the Littauer chair at Harvard for Harry Wolfson gave Judaica its own station on the frontiers of knowledge and pursuit of truth, and began to redress the lopsidedness or imbalance of quasi-Jewish studies. 34

My sense, however, is that the importance of Jewish Studies’ having “its own station” was not well grasped in the Divinity School even as late as the time I arrived here (1988), and for quite an innocent reason: the major focus of faculty and students alike was on Christianity, and that meant that the farther the Jewish material was from intersecting with the church (especially with its two-testament Bible), the less relevance it seemed to have. Sometimes, it even appeared that the very existence of Jews and Judaism beyond antiquity was not altogether appreciated. I still remember that the catalogue cross-listed a NELC course called “Sources of Jewish History: 500–1750” in Area I, “Scripture and Interpretation”—this despite the fact that its earliest material dated to 650 years or so after the latest source in the Hebrew Bible!

Already in his essay of 1921, Moore had lamented the prominence of specialists in the New Testament among those with a penchant for commenting negatively about Judaism without, in the main, finding “it necessary to know anything about the rabbinical sources.” In a mode somewhat reminiscent of Twersky’s two generations later, he found intensely problematic the work of those whose “interest in Judaism also was not for its own sake, but for the light it might throw on the beginnings of Christianity.” 35 It is hard to gainsay this judgment, or to pronounce it obsolete. But there is another side to the issue. Absent the focus on Christianity in general and the New Testament in particular, it is hard to see how most of those laboring under anti-Jewish stereotypes originating in Christianity (whether the individuals profess Christianity or not) will ever have occasion to confront their bias and to approach Jewish sources on their own terms. In that sense, paradoxically, a more religiously diverse and pluralistic academy can prove not less but more subject to the old misconceptions, since the latter have a life and a momentum of their own, quite independent of the ancient theological claims in which they took shape.

Fully 56 years after Moore published “Christian Writers on Judaism,” a New Testament scholar, only this time another American eager to correct the record, opened his own study by terming Moore’s essay “an article which should be required reading for any Christian scholar who writes about Judaism.” 36 As E. P. Sanders went on to show in his now classic study, Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion , in the intervening decades many eminent New Testament scholars had failed to understand the import of Moore’s work and continued to trade in the old prejudicial stereotypes, sometimes even citing Moore against what he was, in fact, saying. 37 Decades after Moore, even after the Holocaust, the old biases were alive and well.

To me, the pressing question is why. Why has the negative presentation of Judaism proven so powerful, so protean, and so tenacious?

One reason, I think, is that it intersects with social prejudice—theological anti-Judaism drawing energy from, and imparting energy to, social anti-Semitism. But another reason is that the old pattern presents a simple but enormously powerful psychological drama—the innocent and peace-loving Jesus murdered by his godless, hypocritical, and legalistic kinsmen. As for the perfidious malefactors themselves, they are rightfully scattered all over the world with no state of their own, surviving as involuntary witnesses to the truth of the gospel, as they “groan in grief over their lost kingdom and quake in fear under the sway of innumerable Christian peoples,” as Augustine had put it. 38

The drama is so powerful, in fact, that, as Jonathan Sacks, now retired as Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth, put it, “it is a virus—and like a virus it mutates.” In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, “religious anti-Judaism,” the variety that we have been considering, “mutated into racial anti-Semitism,” best known for its role in Nazism and the Holocaust. But now what Sacks calls “the second great mutation of anti-Semitism in modern times” is underway, a mutation “from racial anti-Semitism to religious anti-Zionism.” The new strain, he writes, “uses all the mediaeval myths—the Blood Libel, poisoning of wells, killers of the Lord’s anointed, incarnation of evil—transposed into a new key and context,” with the state of Israel as the great malefactor. 39 With the Jewish people no longer stateless, groaning in grief over their lost kingdom and quaking in fear under the sway of innumerable Christian peoples, the old evil is again loose in the world.

It is essential to understand that Sacks is not speaking of those who are critical of this or that Israeli policy, even sharply so. If he were, he would be accusing large segments of the Israeli populace and world Jewry alike. Helpful criteria for distinguishing criticism of Israel from anti-Semitism are given by Alan Dershowitz, now retired as Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. “So long as criticism is comparative, contextual, and fair,” Dershowitz writes, “it should be encouraged, not disparaged. But when the Jewish nation is the only one criticized for faults that are far worse among other nations, such criticism crosses the line from fair to foul, from acceptable to anti-Semitic.” 40 Unfortunately, the long history of Christian anti-Semitism provides a rich and remarkably resilient resource for that singling out of the Jewish state for consistently and univocally negative judgments unreflective of the complexity of the historical facts. 41

This latest mutation of anti-Semitism has indeed produced a virulent strain; only time will tell how hearty it is. Remarkably, another central figure in the history of Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School spotted the danger early on. Krister Stendahl, (1921–2008), an influential New Testament scholar who became dean of Harvard Divinity School (1968–1979) and, later, a Lutheran bishop, wrote in these pages in the wake of the Six-Day War (1967):

In the months and years to come, difficult political problems in the Middle East call for solutions. Christians both in the West and in the East will weigh the proposals differently. But all of us should watch out for the ways in which the ancient venom of Christian anti-semitism might enter in. A militarily victorious and politically strong Israel cannot count on half as much good will as a threatened Jewish people in danger of its second holocaust. The situation bears watching. . . . The present political situation may well unleash a type of Christian attitude which identifies Judaism and Israel with materialism and lack of compassion, devoid of the Christian spirit of love. 42

But if the goal is to think comparatively and contextually and with fairness to the full range of facts, as Dershowitz recommends, then some small solace can be found in the history of scholarship on ancient Judaism and early Christianity since Moore, in which precisely that type of analysis has grown in strength (Stendahl’s own work is an example), 43 and dramatically so in the decades since Sanders voiced his lament. As always, it will take far more than scholarship to counter large cultural and social forces, but, in the face of the new challenge, scholars should underestimate neither their own responsibilities nor the lessons embedded in the history of their own disciplines and the general enrichment that can come when Judaism has its own station and the study of it is pursued for its own sake.

A postscript: Although I have not intended these reflections as comprehensive and have necessarily omitted reference to several notable figures, I cannot close without mentioning one more. My own teacher, Frank Moore Cross (1921–2012), taught at Harvard Divinity School from 1957 until his retirement in 1992, holding the Hancock Professorship, by then in NELC, from 1958. Trained, like his father, as a Presbyterian minister, Cross presided over a genuinely nonconfessional program, which produced a large number of the most prominent Jewish figures in what is now the senior generation of Hebrew Bible scholars. Like Stendahl a great admirer and supporter of Jewish scholarship, he invited a number of prominent scholars from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to be visiting professors, including such influential figures as Moshe Goshen-Gottstein and Shemaryahu Talmon.

- This is also a tradition of immense historical importance to the emergence of ideas of religious tolerance in political thought, as brilliantly analyzed by Eric Nelson of Harvard’s Department of Government in The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought (Harvard University Press, 2010).

- Samuel Eliot Morison, The Founding of Harvard College (Harvard University Press, 1935), 220–21. Morison thanks Harry A. Wolfson for tracking down the reference ( Mishneh Torah, Tefillah 11:14).

- Robert H. Pfeiffer, “The Teaching of Hebrew in Colonial America,” Jewish Quarterly Review 45 (1955): 363–73, at 369.

- Lee M. Friedman, “Judah Monis: First Instructor in Hebrew at Harvard University,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 22 (1914): 1–24, at 2–3.

- See Shalom Goldman, God’s Sacred Tongue: Hebrew and the American Imagination (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 41–45.

- “Rules and Statutes of the Professorships in the University at Cambridge” (Metcalf and Company, 1846), 7–8.

- William T. Baxter, The House of Hancock: Business in Boston, 1724–1775 (Harvard University Press, 1945), esp. 55–56, 69–74, and 114–18 .

- Baruch de Spinoza, A Theological-Political Tractate and Political Treatise (Dover Publications, 1951), 106 and 103. The Tractatus Theologico-Politicus was first published in 1670.

- www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/biographies/george-rapall-noyes . James de Normandie, “Memoir of Rev. Edward James Young, D.D.” in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 44 (October 1910–June 1911): 529–42, at 531–32.

- D. G. Lyon, “Crawford Howell Toy,” Harvard Theological Review 13 (1920): 1–21.

- The name was changed in 1961 to Department of Near Eastern Languages and Literatures and then to its current name at some point in the early 1970s, when your humble—nay, overrated—scribe was a graduate student there.

- See David G. Lyon, “Semitic,” in The Development of Harvard University since the Inauguration of President Eliot, 1869–1929 , ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (Harvard University Press, 1930), 231–40.

- Ibid., 235.

- Willam Wallace Fenn, “George Foot Moore: A Memoir,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 64 (February 1932): 3–11, at 3.

- Quoted in Leo W. Schwarz, Wolfson of Harvard: Portrait of a Scholar (Jewish Publication Society of America, 5738/1978), 38–39, with no indication of the source of Moore’s quote.

- Samuel A. Meier, “Moore, George Foot (15 October 1851–16 May 1931),” American National Biography (online version, 2000), www.anb.org .

- George Foot Moore, “Christian Writers on Judaism,” Harvard Theological Review 14 (1921): 197–254.

- Ibid., 197.

- Ibid., 250.

- Ibid., 202.

- Ibid., 251. On this last point, see Nelson, The Hebrew Republic .

- Moore, “Christian Writers on Judaism,” 251–52. On the latter point, Moore refers specifically to Ferdinand Weber but certainly sees the pattern as much more general.

- Ibid., 252.

- E. P. Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion (Fortress Press, 1977), 56.

- Fenn, “George Foot Moore,” 8.

- For a fine introduction to this important subject, see now Chaim Saiman, Halakhah: The Rabbinic Idea of Law (Library of Jewish Studies; Princeton University Press, 2018).

- A very useful new introduction to the Talmud and contemporary scholarly approaches to it is Barry Scott Wimpfheimer, The Talmud: A Biography (Lives of Great Religious Books; Princeton University Press, 2018).

- Jacob Neusner, “ ‘Judaism’ after Moore: A Programmatic Statement,” Journal of Jewish Studies 31 (1980): 141–56, at 147. The whole article is a good discussion of what Neusner found inadequate in Moore’s procedures.

- Ibid., 142.

- Schwartz, Wolfson , 38–39, 49.

- Ibid., 171.

- Isadore Twersky, “Harry Austryn Wolfson, in Appreciation,” American Jewish Year Book 76 (1976): 99–111, at 107.

- Moore, “Christian Writers,” 241, n. 47. The second comment (on 241 itself) was made about Emil Schürer and Wilhelm Bousset.

- Sanders, Paul , 33.

- E.g., ibid., 55–56.

- Augustine, Contra Faustum 12:12.

- Jonathan Sacks, “A New Anti-Semitism,” Chesterton Review 30 (2004): 199–207, at 202–03. For more detail, in this case involving the revival of the adversus iudaeos tradition among liberal theologians in particular, see Adam Gregerman, “Old Wine in New Bottles: Liberation Theology and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 41 (2004): 313–40, esp. 333–39; idem, “Israel as the ‘Hermeneutical Jew’ in Protestant Statements on the Land and State of Israel: Four Presbyterian examples,” Israel Affairs 23 (2017): 773–93 (Gregerman is an alumnus of Harvard Divinity School); and Jonathan Rynhold, The Arab-Israeli Conflict in American Political Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2015), esp. 130–31. Of course, the religious and racial versions of anti-Semitism are hardly incompatible and can readily energize each other. On this, see Susannah Heschel, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (Princeton University Press, 2008). The same can be said as well for the relationship of anti-Semitism and anti-Israelism.

- Alan Dershowitz, The Case for Israel (John Wiley & Sons, 2003), 1.

- For examples, see Gregerman, “Israel as the ‘Hermeneutical Jew.’ ” It is important to recognize that (1) a great many Christians have successfully rid themselves of the penchant to vilify or even demonize the Jews, and (2) one can be subject to that penchant without being a believing Christian.

- Krister Stendahl, “Judaism and Christianity II—After a Colloquium and a War,” Harvard Divinity Bulletin 1 (1967): 2–9, at 7. On the larger question of the range of Christian theological responses to the resumption of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel, see, for example, Adam Gregerman, “Comparative Christian Hermeneutical Approaches to the Land Promises to Abraham,” CrossCurrents 64 (2014): 410–25.

- See especially Stendahl’s influential essay, “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West,” Harvard Theological Review 56 (1963): 199–215, reprinted in Paul among Jews and Gentiles (Fortress Press, 1976), 78–96.

Jon D. Levenson is the Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies at HDS. His many books include Resurrection and the Restoration of Israel: The Ultimate Victory of the God of Life (Yale University Press, 2006), which won a National Jewish Book Award, and The Love of God: Divine Gift, Human Gratitude, and Mutual Faithfulness in Judaism (Princeton University Press, 2015).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About | Commentary Guidelines | Harvard University Privacy | Accessibility | Digital Accessibility | Trademark Notice | Reporting Copyright Infringements Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Israelization and Lived Religion: Conflicting Accounts of Contemporary Judaism

Adam s ferziger.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2019 Aug 4; Accepted 2020 May 4; Issue date 2020.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted research re-use and secondary analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic.

The article begins with an analysis of Yossi Shain, Ha-Me’ah ha-Yisraelit ve-ha-Yisraelizaziyah shel ha-Yahadut ( The Israeli Century and the Israelization of Judaism ) (2019), which puts forward a novel and enlightening revisionist view of the relationship between Israeli and American Jewries. The second part of the article reveals essential problems with Shain’s central argument. These come to a fore through the study of Judaism as a lived religion. Three examples are discussed at length to illustrate this point: developments in the religious lives of liberal Jews, Chabad, and Orthodox Feminism.

Keywords: Israel, Israelization, Yossi Shain, Jewish world, Diaspora, Judaism, Religion, Lived religion, Charles Taylor, Yuri Slezkine, Chabad, Religious feminism, American Judaism

The complex interface between the State of Israel and Jewish life throughout the world has drawn considerable attention in the past few years. Numerous high-powered conferences have been held (Borschel-Dan 2018 ; Kraft 2019 ; Kustanowitz 2019 ), studies and books have appeared (D. Waxman 2016 ; Gordis 2019 ), 1 and new organizations have been established with the express goal of addressing what has been deemed by many to be a growing “distancing” (Halutz 2015 ; Ravid 2018 ; Mlotek 2019 ; Tibon 2019 ). 2 In the spring of 2019, a Hebrew book appeared that engages the underlying foundations of the contemporary relationship through a truly provocative “paradigm-changing” thesis.

Yossi Shain’s Ha-Me’ah ha-Yisraelit ve-ha-Yisraelizaziyah shel ha-Yahadut ( The Israeli Century and the Israelization of Judaism ) ( 2019 ) puts forward a revisionist view that moves past the novel and jarring to the partially convincing. Deeper examination, as I will argue in the second part of this article, reveals essential problems with the author’s central argument. Nonetheless, exposure to the fresh approach itself stimulates thinking and facilitates efforts to sharpen perceptions.

Shain, a Tel Aviv University political scientist who until recently held a concurrent appointment at Georgetown University in Washington DC (Rosner 2018 ), challenges the notion that Israel and the Diaspora are, as a well-regarded 1990 study emphasized, Two Worlds of Judaism (Liebman and Cohen 1990 ). Rather, he presents a picture of a Jewish globe with Israel at its center. His core claim is stated already on the first page of the monograph: “Since its establishment in 1948, the State of Israel has gradually situated itself as the most important factor in all areas of worldwide Jewish life.…The nation of Israel and Jewish civilization are defined today more than ever through the political, military, and cultural power of the sovereign Jewish state” (Shain 2019 ).

As the discussion moves forward, I will offer an alternative perspective to Shain’s thesis through the prism of counter examples from the lived religion of contemporary Jews. The first part of the article, however, is devoted to a detailed explanation and examination of his core paradigm. To focus a comparative lens on Shain’s unique viewpoint, as well as to set the stage for my subsequent analysis, I will begin with a brief foray into Charles Taylor’s already-classic 2007 tome, A Secular Age ( 2007 ).

A Secular Age; an Israeli Age

Taylor’s ( 2007 ) work addresses the ongoing academic debate over the degree to which the Western world has become secularized. Most previous discussions of the subject revolved primarily around demonstrating that secular ideals, forces, and institutions in the world were expanding and gaining greater acceptance while religious ones were declining. The deterministic understanding that secularization was advancing in a linear fashion, highlighted in books such as Peter Berger’s The Heretical Imperative ( 1979 ), was challenged by the resurgence of religious fundamentalism that characterized the 1980s and beyond. Indeed, Berger ( 1999 ) himself eventually offered a more nuanced interpretation in light of these upheavals. Taylor, in contrast, is more convinced than ever that the core of contemporary Western civilization is situated in the secular realm. The source for his position, however, is an account of the role of secularism in society that does not depend on the ups and downs of one side or the other. Alternatively, the key factor is what he calls “the conditions of belief” (Taylor 2007 ).

What distinguishes the current era, according to Taylor, is that regardless of one’s own personal religious stance, in Western society the point of departure for how to perceive the world is the secular one. That is, on the one hand, scientific truths and ideal political structures that are completely independent of parochial authority and belief are taken for granted as the normative framework of society. On the other hand, acceptance of religious and spiritual ideals demands digressing from or denying that which is clear cut and assumed. This stands in contradistinction to previous times when the opposite was the case. Religious principles of belief and practice were the guiding paradigm, and individuals like Spinoza, who challenged these presumptions, were deviants. In the current condition, religion has not disappeared, nor, for the most part, has it been completely dismissed. Yet it is no longer the foundation of authority or truth. It is simply a choice, and far from the obvious one. As Taylor put it:

[T]he change I want to define and trace is one which takes us from a society in which it was virtually impossible not to believe in God, to one in which faith, even for the staunchest believer, is one human possibility among others….

Secularity in this sense is a matter of the whole context of understanding in which our moral, spiritual or religious experience and search takes place….

An age or society would then be secular or not, in virtue of the conditions of experience of and search for the spiritual. (Taylor 2007 , 3)

Once this “presumption of unbelief” has become dominant, even those who continue to believe staunchly, according to Taylor, operate in a secular milieu.

Unlike Taylor’s, Shain’s book is not a work of philosophy. It combines a multidisciplinary examination of the contemporary Jewish world with a teleological metanarrative of Jewish history from ancient times that adumbrates his reading of current realities. It certainly addresses religious people and groups, but, as opposed to Taylor, he is not particularly interested in what is going on in the minds of believers and nonbelievers. Shain is a political scientist for whom what counts most of all is where the center of power sits. But power, as the book articulates, is not defined exclusively through military and economic strength nor political allegiance. Power is also about how a certain body, here the sovereign Jewish state, impacts upon the lives of others—especially Jews but not only.

Thus, there is a core analytical perspective that underlies both volumes. In parallel to Taylor’s “conditions of belief,” what characterizes the “Israeli century” is not that the State of Israel is incrementally achieving consensus among all Jews. The main change is that regardless of whether one lives in Israel or not, or identifies with the Zionist project or not, Israel has become the central issue around which both Jews and non-Jews worldwide engage Judaism. Israel is for twenty-first century Jews what secular constructs are for most Western individuals: the foundational element that frames most other Jewish involvements, ideological positions, political activity, and cultural production. In point of fact, according to Shain, Israel is also the predominant factor in non-Jewish engagement with Judaism—again, for those whose relationship is positive as well as for those who are neutral, antagonistic, or seek to harm (Shain 2019 ).

Israelization

Shain is undoubtedly an ardent Zionist who celebrates the renaissance of Jewish political, military, and economic power, and the rise of a sui generis Israeli Jewish culture. Indeed, he maintains that it is becoming clear to most Jews that their personal security is dependent on a strong Israel. Nonetheless, unlike the founders of the State—many of whom negated Diaspora life and dedicated their efforts toward immigration (Schweid 1984 )—or, for that matter, the eminent contemporary novelist A. B. Yehoshua ( 2006 ), Shain’s is a global vision built around a robust Israeli center. American Jewry is undoubtedly still a rich and powerful Babylon; but the parallel phenomena of rising Israeli strength, heightened antisemitism, and radical assimilation have left it playing second fiddle. While no longer predicating its relationship to world Jewry on the hope that they will find their inner “Zerubabel” and take up the “Cyrus challenge” to return home, it is Israel, advances Shain, which sustains its distant kin to an ever-greater degree.

Israel’s centrality to Jewish life, according to Shain, is reflected in its critical mass of Jews, destined within a few years to outgrow the rest of the world’s Jewish population, and the diverse, hyper-creative, and multicultural Jewish environment that it has facilitated (DellaPergola 2018 ). Israeli academicians, writers, musicians, cinematographers, and “start-up-ists” have achieved a global footprint and nourish Jewish pride in communities across the planet (Senor and Singer 2009 ).

From an opposite point of view, the past few years have witnessed numerous examples of figures such as billionaire world Jewish leaders Charles Bronfman and Ronald Lauder, who have complained publicly that Israel is either insensitive or completely disregards the needs and ideals of Diaspora Jews. In May 2018, for instance, Bronfman declared the need to create a more intensive dialogue between Diaspora Jews and Israel:

But do Israelis care enough about what happens in the global Jewish World?…. Let’s establish a permanent, serious lobby in Jerusalem including both Israeli and North American Jewish groups. The time has come to demonstrate both the negatives as well as the positives that proposed Israeli legislation will have on North American Jewry. At the same time, we must heighten awareness of our vibrant communities, their importance to Israel and their real need to be recognized as full partners. (Bronfman 2018 )

For the most part, newspapers and pundits perceived this pronouncement as reflecting intensification of the “distancing” trend from Israel that has reversed in recent decades the “love affair” that characterized the post-1967 era. In Shain’s eyes, however, such remonstrations—justified or not—reify the degree to which contemporary Jewish life revolves around and is dependent upon its Jerusalem center.

Israel is committed to protecting the lives of all Jews wherever they choose to live asserts Shain. Moreover, as opposed to North America, where due to assimilatory trends Jewish continuity is becoming tenuous, it is the State of Israel, where the nation feels rooted and secure in its national identity. This enables Jews to realize their globalizing talents without undermining their deep links to their singular tradition and culture “The deep sense that one has a home to return to enables them to traverse and engage the big world with ease and confidence” (Shain 2019 , 14). Thus, the proliferation of expatriate Israelis who have settled in Silicon Valley, Southern Florida, and Berlin does not indicate a decline in the Zionist ideal. It is, rather, a testament to the fortitude and long-term stability of the Jewish state. These individuals generally maintain close ties with the “mother country.” They follow news from “back home” vigilantly and serve as cultural agents who communicate “Israeliness” to their Diaspora brethren. Their successes are Israel’s successes (Shain 2019 ).

Israel’s own economic prowess, says Shain, combined with the increasing role of Israelis in North American Jewish life, have neutralized its former dependency on the “rich American uncle.” If anything, there is a role reversal in which Israel provides a security blanket, not just on a physical level but for Diaspora Jewish identity. The preeminent example of this phenomenon is the Birthright ( Taglit ) program. Since its inception in the late 1990s, it has brought more than 600,000 young adults to Israel for ten days of intensive Israeli and Jewish immersion. In the eyes of Jewish leaders both in Israel and throughout the world, it is considered to be the most successful Jewish educational initiative of the past few decades and a key to fortifying Diaspora Jewish life (Kelner 2010 ; Abramson 2017 ; Shain 2019 ).

In parallel to those who turn to Israel for inspiration, a vocal and growing constituency of Diaspora Jews feels alienated from its power and nationalist orientation, especially as reflected in its policies toward Palestinians. For them, explains Shain ( 2019 ), this is the opposite of the universalist, humanitarian, tikkun olam -oriented Judaism upon which they were nurtured. 3 Some protest or look for ways to strengthen Israeli groups that advance alternative approaches. A growing minority support boycott, divesture, and sanction (BDS) initiatives, aimed to punish Israel for its policies and pressure it to change them, and/or question the very legitimacy of a Jewish nation-state. On this conflict, Shain makes his opinion clear. While certainly opposed to unrestrained force when it can be avoided, in the Niebuhrian debate between sovereignty and humanism, he chooses the former (Niebuhr 1932 ), not due to an all-out rejection of liberal values, but because from his view a state cannot function by the same rules as powerless individual Jews living under the control of others (Gordis 2019 ; Shain 2019 ). Yet in his scheme of Israelization, which is predicated—as emphasized above through the comparison with Taylor—on the “conditions of belief” rather than the belief itself, those Jews who are ambivalent about Israel or even adopt the other side completely are drafted to support his contention. Inasmuch as they protest their distaste or repulsion, it is Israel that drives their passion.

Here Shain leans on, among others, the work of Israeli literary scholar Gitit Levy-Paz (Levy-Paz 2016 ), who has highlighted the propensity of contemporary American Jewish writers to place Israel and its foibles at the center of their novels. In the past decade, leading authors such as Michael Chabon, Nathan Englander, Nicole Krauss, and Jonathan Safran Foer have all published works that grapple with their ambivalence toward the Jewish state and its political and religious character. Chabon in particular is outspoken in his reproach of the Israeli government and produced a novel, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union ( 2007 ), which renders a counter-history in which Israel actually never came into existence. In Shain’s eyes, Chabon’s “criticism manifests connection” ( 2019 ). He cites, as well, Englander’s own testimony to the obsession with Israel of him and his American Jewish colleagues: “I really don’t know what got into us…somehow Israel eats away at us. While it is difficult to compare my book to those of other friends in our Jewish mafia…among them too, Israel is in the background” (Shmilovitz 2018 ). Summing up the connection between these Jewish writers and Israelization, Shain declares: “[A]longside Israeli Hebrew literature, there is also literature being produced in the Diaspora that is characterized by its relationship to Israeli sovereignty. It is not written in Hebrew, nor in the territory of the motherland, but its focus is the Israeli century” ( 2019 ).

In the Israeli century, antisemitism has by no means disappeared. On the contrary, there is consensus that the last decade has witnessed a major uptick in public outbursts of Jew-hatred throughout the globe, and not just in European countries whose deeply-rooted phobias regarding Jews find strange bedfellows with some elements within Muslim constituencies—ironically themselves the victims of some of the same prejudices. Even in the United States, where Jews have felt especially safe, this is no longer necessarily the case, as the two murderous synagogue attacks of 2018 and 2019 in Pennsylvania and California revealed tragically (Pink 2019 ). Even though these remain isolated and unusual events, the ubiquitous police patrol cars and armed guards along with congregational volunteers in front of most large synagogues give visual expression to the sea-change in the rhythm of contemporary North American Jewish life.

Shain is fully aware that there are multiple factors that foster antisemitism. Yet he asserts that the critical distinction between contemporary trends and those of the past is the fusion by so many of anti-Israel attitudes with loathing of Jews. To be sure, non-Jewish anti-Israel activists—as well as Jews who are alienated from the State and cultivate cosmopolitan identities that are independent of, if not antagonistic to, Zionism—argue that anti-Zionism and antisemitism are dissimilar. All the same, as Shain emphasizes, such distinctions are not borne out by radical Muslim efforts to introduce classical tropes of antisemitism into the discourse of the current conflict (Litvak 2006 ), nor, as figures such as French-Jewish intellectuals Bernard-Henri Lévy (Efune 2015 ) and Alain Finkielkraut ( 2004 ) have argued, by other manifestations of public antisemitism throughout the world. Indeed, Shain gives his imprimatur to a term coined by others, the “Israelization of antisemitism” ( 2019 ).

Even more acutely than the conflation of anti-Israel attitudes with Jew-hatred, Shain’s Israeli century is characterized by a transformation in the ways Jews respond to antisemitism, with the existence of Israel and the power that it wields being game-changers on multiple levels. For example, in parallel to the antipathy that Israeli power has engendered, Israel possesses unprecedented tools for engaging enemies of the Jews. The Mossad intelligence agency, for example, has a division called “ Bizur ” that is charged with assisting Jewish communities throughout the world in protecting themselves. Its agents train local Jews in self-defense and surveillance. Since the 1990s, as described by Israeli investigative journalist Yossi Melman (Melman 2010 ), some of its alumni have also set up private companies in the West that specialize in providing solutions to congregational and communal security concerns (Shain 2019 ).

On another level, countries that in the past tolerated and even promoted antisemitism recognize today that there may be a price to pay in terms of their economic and diplomatic relations with Israel. To be sure, sometimes the Israeli government itself downplays anti-Jewish statements and policies in other countries in furtherance of diplomatic and economic interests. Notwithstanding, there are numerous examples that suggest that Israeli relations with such governments cause their leaders to hedge their populist, nationalist-oriented positions in order to prevent a strong Israeli backlash (Keinon 2017 ; Ahren 2019 ). What is clear in recent years, moreover, is that Arab regimes, such as Dubai, Bahrain, and even Saudi Arabia and Oman, which in the past downplayed or prohibited a public Jewish or Israeli local presence, have openly nurtured local Jewish communal life and opened their doors to Israelis (J. Ferziger and Odenheimer 2018 ). Here, Israel’s economic and political assets have not only resulted in the Palestinian issue looming less large but have neutralized the confluence of antipathy to Israelis and Jews that once reigned. Just as historians asserted that the modern racial-oriented antisemitism that arose in the nineteenth century differed in fundamental ways from its medieval and ancient ancestors (J. Katz 1982 ), so too has antisemitism and responses to it been altered, in Shain’s scheme, by the now-established and stable Israeli sovereign state.

Toward the end of the book, Shain shares some of his own concerns and criticisms regarding the post-1967 borders and current settlement policies. His core thesis, however, stands independent of these predilections. For, as he asserts throughout, regardless of whether one sympathizes with or strongly opposes specific Israeli policies or even Israel’s existence, the crucial issue is that the “conditions” have changed. In the Israeli century, then, both anti-Judaism and Judaism itself have been transformed.

A Babylonian Legacy: Slezkine’s Jewish Century

The title of Shain’s book alludes to University of California historian Yuri Slezkine’s equally provocative 2004 work, The Jewish Century (2019, New Edition). Shain’s work contains a critique and provides a stark alternative to the prior publication. By referencing Slezkine briefly, I seek to illustrate the degree to which these two monographs may be seen as representing the poles of the contemporary “Jerusalemian” versus “Babylonian” perceptions of Judaism (Rawidowicz 1957 ). That said, I will then point to a commonality between them that will serve as the foundation for my critique of Shain.

Slezkine also thinks about Jews in global terms. But unlike Shain, who celebrates the transformative impact of territoriality, sovereignty, and homeland for Jews both in Israel and outside it, Slezkine does just the opposite. He defines the Jews as the most successful example of “Mercurian” nations in history that functioned according to alternative patterns of existence from those of most territorially-based collectives, “specializing in the delivery of goods and services to the surrounding agricultural or pastoral societies” (Slezkine 2019 , 7). The Mercurian groups share a common destiny of combining exceptional economic success with rousing antagonism and resentment in their hosts.

According to the Russian-born and trained Slezkine, due to their unusual talents, Jews have increasingly influenced the trajectory of the Western world. He presents the vital role of Jewish intellectuals and activists in the Bolshevik Revolution and the first decades of the Soviet Union as exemplary of the success, impact, and hostility associated with their “Mercurian” identity. As such, he argues that one of the boldest trends in modern history is the affirmation and adoption by others of the Jew’s model of existence. As an ideal, modern identity means being “urban, mobile, literate, articulate, intellectually intricate, physically fastidious, and occupationally flexible” (Fox 2005 ). As Stephen Whitfield put it in a trenchant review, “for…Yuri Slezkine, the Jews are modernity—and everything in his flamboyant account of their fate over the past century follows from that equation” ( 2006 , 316).

Slezkine admits that “Zionism prevailed over communism…because nationalism everywhere prevailed over socialism” ( 2019 , 363). In the process, however, this “most eccentric of nationalisms,” in which Jews tried to be like the rest of the world, sacrificed at the altar of sovereignty the authentic Mercurian characteristics that had made the Jews so successful in the early days of the Soviet Union. For it was the establishment of the State of Israel, he asserts, that reactivated government-sanctioned antisemitism in mid-twentieth century Stalinist Russia.

Despite the decline of the Jewish role in the Soviet Union, the parallel setting, capitalist America “the least revolutionary…——proved the most successful” (Slezkine 2019 , 367). In the United States, says Slezkine, they landed “in a country founded by Protestant Mercurians in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and [could] take their place alongside all the other Mercurianized immigrant groups as part of a general celebration of American ‘diversity’ and ‘ethnicity’” (Lazare 2005 ). Thus, it is in the twenty-first century United States where the legacy of “The Jewish Century” continues to unfold.

Shain too applauds the achievements of American Jewry throughout his book. However, he opines, their profound successes have also led to their demise as a cohesive collective: “All those characteristics that Slezkine projects as American Jewry’s greatness, are the same ones that are incrementally causing its internal obliteration as a unique ethnic group” (Shain 2019 , 14). Under these circumstances, Shain argues, “Its ongoing existence as a Jewish community is increasingly dependent on identification with the State of Israel and connection with it. It is the State of Israel, where the nation feels rooted and secure in its national identity, that enables Jews to realize their globalizing talents without undermining their deep links to their singular tradition and culture” (Ibid.).

Political Religion

Despite their diametrically opposed understandings of what constitutes Jewish impact and the importance of ethnic continuity, Slezkine and Shain share a common underlying approach as far as religion is concerned. Their core theses are predicated on a political perception of religion that highlights its macro-effect on collective life. Their principal concerns are not with theological or ideological content or spiritual movements onto themselves, and certainly not actual practice, but on how the social manifestations of these concepts may impact political and cultural structures. Slezkine says so explicitly. In an interview that took place after the 2017 publication of his book on the Russian Revolution, he attested:

All movements commonly known as “religions” are political. Pontius Pilate, whatever his private reservations, had good reasons for wanting Jesus out of the way. And who doubts the political nature and success of early Islam?

My own preference is to drop the word “religion” altogether. It impedes communication and blinds people to connections they would otherwise find illuminating. Can you think of a definition of “totalitarianism” that would not apply to Christianity, Islam…? The fixation on the need to keep “religions” separate is the only reason most scholars consider Nazism and Bolshevism bizarre modern inventions. (Slezkine et al. 2018 )

Shain is not averse to the term religion nor to engaging parochial matters. Parsing the role of religion in his work, therefore, is more complicated. Yet a review of his discussions of religion within the book demonstrates that he too perceives it primarily in political terms.

In parallel to dismissing the transformation by Slezkine and others of the wandering Jew into a romanticized ultimate cosmopolitan modern, Shain acknowledges the potency of certain religious motifs during various periods of Jewish history as well as in contemporary times. Chief among the present ones in the Diaspora is the translation by liberal American Jewish denominations of humanistic values into the preeminent religious mandate of tikkun olam . Inasmuch as he appreciates this pristine ideal, as noted, he opposes its blanket imposition on the activities of the sovereign state. In point of fact, he sees the tension between “Jewish morality and sovereign morality” as fundamental to the conflict between American and Israeli Judaisms (Gordis 2019 ). Far more confident as he is in the long-term sustainability of Israeli Jewry than its North American counterpart, it is clear which of the two “moral” callings has the upper hand (Shain 2019 ).

Regarding Jewish religious life in the State of Israel, here too Shain engages aspects of religious ideals and practice. Their significance, however, is essentially political—how they reflect the centrality of sovereign Israel for Jewish life. Four topics exemplify this rendering: the concept of Israeli Judaism, conversion, Religious Zionists and theocracy, and the Haredim .

Citing the recent book Yahadut Yisra’elit (Israeli Judaism), co-authored by journalist Shmuel Rosner and demographer Camil Fuchs, both Israel-based, Shain highlights their argument that over its first seven decades Israel spawned a new type of Judaism that is rooted in statehood. While the majority of Israelis do not self-identify as observant ( dati ), they actually see Jewishness as fundamental to who they are. As such, unlike among North American Jews, where intermarriage has accelerated dramatically and participation in both private and public Jewish rituals has declined, there is considerable consensus among Israeli Jews regarding endogamy as well as the maintenance of certain religious elements, particularly Sabbath and holiday meals and rituals, and lifecycle ceremonies. To be sure, many chafe at the coercive aspects of Israeli public religion, but in areas where they have complete free choice, the majority integrate religious symbols and practices into their lives on a regular basis (Rosner and Fuchs 2018 ).

Shain does not explore the spiritual motivations that might be involved; rather, he emphasizes the role of religion as the common culture of the sovereign state. In the words of Rosner and Fuchs:

For most Jews in Israel, living in Israel defines being a good Jew.…We just explained that most Israelis see themselves first and foremost as Jews. Now it becomes clear that for most Israelis to be a good Jew means to live in Israel—to be an Israeli.…In other words: to be first and foremost a Jew, one must first and foremost be an Israeli….Jewishness and Israeliness mix together into a new formula. There are parts that are exclusive to the observant, and others that are actually emphasized more among the nonobservant. But there is much that is shared by all, or almost all. These are the seeds of a renewed culture, Israeli Judaism.…A culture in which to be a “good Jew” means both to “uphold holidays, ceremonies, and customs” and “to serve in the IDF [Israel Defense Forces]” or “to educate toward IDF service.” (Rosner and Fuchs 2018 , 82)

According to Shain, this novel hybrid formulation, which is so much a product of the sovereign reality, offers a fresh and secure path to the future for the Jewish religion. His reading, of course, assumes that such a civil construct is equivalent to a religious life. From a political perspective it certainly can be seen this way. Alternatively, if one perceives religion as more than a “movement” or cultural product, then Shain’s conclusions here are less clear cut.

As to the highly contentious issue of conversion, Shain acknowledges the challenges and insult implicit in the lack of Israeli recognition of non-Orthodox change of status. Yet he highlights those studies that demonstrate that formal conversion has become far less of a barometer for inclusion within the State of Israel. Invoking the terminology put forward by political scientist Asher Cohen, Shain raises the fact that many Russian-speaking immigrants adopt the main features of Israeli Judaism without actually going through the rabbinate’s giyur (conversion) process. Rather, these “non-Jewish Jews” attain their status through the “sociological conversion” that takes place when one lives over time in an Israeli-Jewish city or town, sends one’s children to public school and then to the army, takes off on public holidays, and even adopts some of the rituals observed by most Israelis (Cohen 2005 ). Once again, for Shain, like Slezkine, religion is ultimately a political act.

This model of Israeli-Jewish identity, as Shain emphasizes, also sheds light on processes taking place among Israeli Arabs. According to a number of indicators, the longer they live under Israeli sovereignty, the more they adopt the major culture and reject efforts to cultivate institutions that are run in Arabic and are exclusive to them. That said, Shain rejects the possibility of an eventual “Herodization” or “political conversion” of the Arab population. Rather, he sides with the position that without a solution to the Palestinian issue, Israeli democracy will be unsustainable.

In respect to the future of the sovereign state, of equal concern to Shain are the impacts of two Jewish groups—both religious, the Dati-Leumi (National-Religious) and the Haredim (Israeli ultra-Orthodox). In each case, it is not their religious outlooks per se that spark his alarm but the impact that they can potentially have on the stability of the State, i.e., the ongoing strength of the Israelization process.

Regarding the National-Religious, the main issue for Shain is their growing influence on the IDF. If in the past the offspring of the secular elite dominated the key combat units and officers’ ranks of the Israeli army, today many of the best and brightest prefer to serve in the 8200 division, the unit famous for cultivating some of the “start-up nation’s” most advanced high-tech innovations and nurturing many successful entrepreneurs. During the past two decades, by contrast, soldiers from National-Religious Zionist homes—often graduates of pre-army mechinot [preparatory academies] programs that espouse a redemptive approach to mamlachtiyut [statism] in which army service reflects a religious imperative—have increasingly populated crack units and reached high-ranking positions (Fischer 2011 ; Rosman-Stollman 2014 ). Shain is deeply concerned about the potential for this sector to advance theocratic goals through its military prowess. All the same, he is relatively confident that—as demonstrated during the 2005 withdrawal from Gaza—their allegiance to the authority of the sovereign state will hedge against such a scenario (C. Waxman 2008 ).

As to the Haredim, Shain is far more alarmed. For unlike their Zionist religious cohorts, “[t]he animosity of many within Haredi society to sovereignty and to the modern values of the State of Israel is a time bomb” (Shain 2019 , 281). This negativity is reflected in attitudes towards army service and other state institutions or values, such as the courts, gender equality, secular education, and the ascendancy of allegiance to halakhah over state law. Combined with the demographic trends that forecast the ongoing massive growth of this population and the widespread poverty among many of its members, Shain sees a collective existential crisis in the making (Shain 2019 , 297).

In this light, he cites the work of Kimmy Caplan ( 2007 ), who has pointed to the “Haredization” of Israeli religious society that was manifested in particularly extreme geographical and cultural enclavism among some Haredi subgroups from the late twentieth century. Shain also notes that both Caplan ( 2007 ) and Benjamin Brown ( 2015 ), among others, have shown that counter trends among the Haredi sector have gained traction that are indicative of greater integration into broader Israeli life and less hostility toward the state than in the past.

Ultimately, however, for Shain the litmus test of any aspect of Israeli society, and, for that matter, contemporary Judaism, is its relationship to the sovereign center. Thus, in a telling apocalyptical description, he presents Haredi Judaism as the archetype of Diaspora Judaism—a “demonic” force that may yet undo the Israelization process:

In the struggle between modernity and halakhah, extreme factions have emerged in Israel that are reminiscent of the Judean Desert Sect, who were recorded in the Qumran (Dead Sea) Scrolls and enshrined in history as those whose struggle in the name of religious purity against the Hasmonean state led to bloodshed. It is likely that history shall not repeat itself and such scenarios are one-time events, but it is hard to refrain from gazing once in a while in that direction. (Shain 2019 , 297)

Shain indicates his awareness that drawing such knee-jerk doomsday parallels is an emotional response, yet he does not attend to the fact that his overall analysis of the Haredim digresses from the core argument of his book. Like other religious groups, he perceives them through a political lens. Yet his discussion of Haredim stands in contrast to his central Taylor-like focus on “conditions” and reactions to a new reality that avoids giving grades such as “more or less modern” or “more or less Zionist.” Rather than the degree to which Israel’s very existence shapes them and their responses, Haredim are evaluated based on their actual attitudes toward sovereignty and modernity. And indeed, due to Shain’s perception that they represent the old “Diaspora”-inspired Judaism, they epitomize the antithesis to the Israeli century. Here, then, he falls into the old trap of “negation of the exile” as a foundation for Israel’s centrality—precisely the formulation for which his core thesis offers a fresher and less partisan approach.

Indeed, it would appear that Shain’s anxiety over Haredi influence is so entrenched that even when he presents striking examples of the transformational impact of Israeli sovereignty on this sector, he abandons the sanguinity that typifies every other instance of Israelization in the book. “The cardinal question for the future of the State and Israeli society,” he avers, “is to what degree the Israelization of both Israel-based and American Haredim will eventually lead to a Haredization of Israel. This scenario…will not only undermine the freedom that characterizes the State but sovereignty itself” (Ibid., 38).

The World of Contemporary Lived Judaism

Until this point I have engaged critically with some of the key ideas and dissections that appear prominently in Shain’s forceful tome. The parallel drawn with Taylor’s A Secular Age ( 2007 ) emphasizes the novelty of Shain’s model that argues for Israel’s centrality to contemporary Jewish life based on its impact on Jews rather than the degree to which they support it or move there. Furthermore, I have examined more closely some of his main discussions of religion and religious groups, highlighting his political perception that homes in on the ways that specific factions and their ideals manifest or contest the realities of an entrenched and secure sovereign Israeli state.

I will now raise relevant examples from key Jewish religious trends that challenge aspects of Shain’s core proposal. This succinct encounter with major components of contemporary Judaism offers a framework for examining the Israelization thesis from the perspective of lived religion (Hall 1997 ). Therefore, three phenomena that have strong visibility and bearing on Judaism outside of Israel are introduced as litmus tests: liberal (non-Orthodox) Judaism, the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement, and religious feminism. Each of these have representations in Israel, yet the first is primarily Diaspora-focused, while the others reveal global or transnational characters. My questions, then, are whether these instances also fit Shain’s Israelization model such that their core existences are framed by the “conditions of experience” emanating from the reality of the State of Israel. Do these key manifestations of twenty-first century Judaism provide compelling evidence regarding the degree to which the condition of Israeli sovereignty, as defined by Shain, is or is not central to their current characters?

Liberal (non-Orthodox) Judaism

On May 19, 2019, Elliot Cosgrove, a keen observer of contemporary Jewish life and rabbi of New York’s Park Avenue Synagogue, a prominent Manhattan Conservative synagogue with a 1700 family membership (Ghert-Zand 2018 ), published an op-ed article that seemingly both encapsulated and buttressed Shain’s thesis:

These days, American Jews no longer debate who wrote the Bible. Instead, we argue about Israel. Israel is what brings us together and what tears us apart. We work to keep our relationship with Israel strong and are anxiety-ridden at signs of its weakening. We fear for our children’s encounters with anti-Zionism on campus, and we hope that they sign up for Birthright trips. The labels that delineate our denominations are no longer based on belief or observance—Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist—but on our views about Israel: AIPAC, ZOA, JVP, J-Street and the rest of the alphabet soup of Israel advocacy.

Despite the fact that we do not live, vote, serve in the military or pay taxes there, Israel has become the organizing principle and civil religion of American Jewry.

…While Jewish sovereignty is a cause for celebration, American Jews are still seeking to come to terms with this new reality. (Cosgrove 2019b )

Cosgrove’s comments reflect the “postdenominational” ambience of twenty-first century American Judaism in which religious movement labels play less of a role in personal Jewish identification. But as Jack Wertheimer ( 2005 ) warned already in 2005, along with its many blessings a less contentious environment also brings with it an atmosphere of complacence. Enter Israel, a topic that increasingly divides American Jews and, in the process, elicits considerable passion on all sides.

Cosgrove, however, laments this condition because he perceives it as a deflection—a way to avoid addressing the core existential issues for American Jews:

Clearly, it is easier to take someone to task for their views on Israel than [ sic ] it is to come face-to-face with the withering of Jewish identity in one’s children and grandchildren. If Jews spent less time attacking each other on Israel and more time building Jewish identity, devoted fewer resources to supporting the extremes of the Israel debate and more to making Jewish day school education, camping and synagogue life affordable, American Jewry would be in better shape, and so would our relationship with Israel.

Why do American Jews talk about Israel so much? Because it is easier than turning the lens on the endangered condition of our Judaism. (Cosgrove 2019b )

Shain would likely argue that this scenario is by no means a matter of collective avoidance. Rather, it reflects the natural, one might even say deterministic, consequence of the progressive process of Israelization. In the Israeli century, the theological and ideological debates that once dominated the religious engagements of the American Jew have been upstaged by the transformed “conditions of experience” associated with rooted sovereignty.

Indeed, in his brief discussions of the relationships of the Conservative and Reform movements toward Israel, Shain emphasizes the fact that each see maintaining a campus in Jerusalem as a reflection of the criticality of the Jewish state to their values. This, he notes, is an exceptionally profound statement when coming from the Reform movement, whose leadership initially opposed Zionism and for many years expressed considerable ambivalence. Moreover, the fact that these constituencies have become so vigilant in protesting Israel’s exclusive recognition of Orthodox standards of conversion, marriage, divorce, and rabbinic qualifications only testifies, in the eyes of Shain, to the elevated role that Israel plays in their Jewish self-understandings.

Yet Cosgrove’s ( 2019b ) protest suggests that gauging what epitomizes people’s Jewishness primarily based on what side they take on a particularly contentious issue is not the only way nor the most accurate one, for such passion when unaccompanied by rigorous activism is “easy” and is not necessarily the central element of their Jewish connection. In this context, Werthheimer’s The New American Judaism ( 2018 ), a 2018 National Jewish Book Award winner, points to an alternative perspective to that of Shain’s regarding the religious nexus of non-Orthodox American Jews.