What does contagious laughter sound like?

15 December 2020

Many mammals – such as rats, dogs, chimpanzees, squirrel monkeys and other primate species – produce laughter-like vocalisations when playing with their peers. Laughter provides a unique perspective on vocal signalling behaviour because it plays a role in both one-on-one interaction and interaction among larger groups. Humans begin laughing soon after their birth, at the age of around three months. This is long before they start talking. Human laughter is universal. ‘One of the most interesting characteristics of laughter is its contagiousness,’ says Roza Kamiloglu, who is conducting the research together with her colleague Disa Sauter and five of their students. ‘But what does contagious laughter actually sound like and what makes one laugh more contagious than another? That’s what we aim to find out with our experiment .’

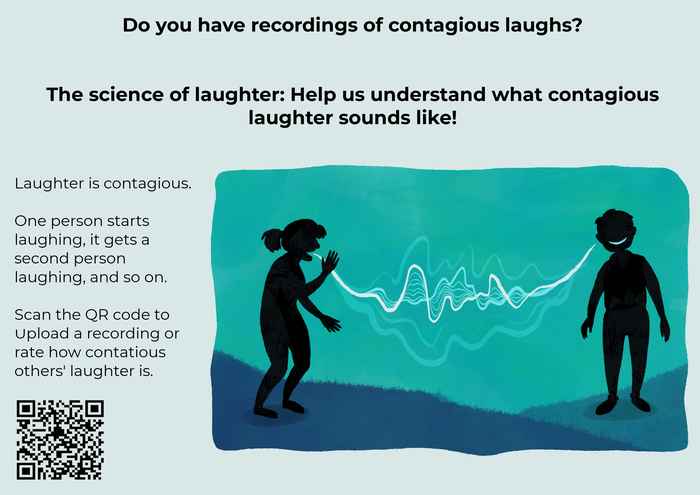

Join the laughter

Laughter has a range of social functions. It can serve to reduce tension between people, but can also be a way of bonding with others. By laughing along with someone else, you can show that you find this person attractive or pleasant or that you feel a bond with them. Kamiloglu explains: ‘In our experiment, we ask the participants to assess fragments of laughter on their level of contagiousness, on a scale from 1 to 5. We also ask them if they think the laugh was produced by someone from their own culture or a different culture.’

The researchers hope to gather a large amount of data, which will then enable them to identify and analyse the variability of contagious laughter. As part of this process, they will examine the acoustic characteristics of contagious laughter as well as the context in which contagious laughter occurs (for instance, when watching a comedy film or laughing at a joke) and demographic data, such as the sex and age of the laughing person. The experiment is being carried out in several languages: Dutch, English, German and Polish.

Want to get involved?

Go to the experiment website . You can rate as many laughter fragments as you like. The experiment will run until 1 February 2021.

Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences

Programme group Social Psychology

Cookie Consent

The UvA uses cookies to measure, optimise, and ensure the proper functioning of the website. Cookies are also placed in order to display third-party content and for marketing purposes. Click 'Accept' to agree to the placement of all cookies; if you only want to accept functional and analytical cookies, select ‘Decline’. You can change your preferences at any time by clicking on 'Cookie settings' at the bottom of each page. Also read the UvA Privacy statement .

Study: Laughter Really Is Contagious

If you see two people laughing at a joke you didn't hear, chances are you will smile anyway--even if you don't realize it.

According to a new study, laughter truly is contagious : the brain responds to the sound of laughter and preps the muscles in the face to join in the mirth.

"It seems that it's absolutely true that 'laugh and the whole world laughs with you," said Sophie Scott, a neuroscientist at the University College London. "We've known for some time that when we are talking to someone, we often mirror their behavior, copying the words they use and mimicking their gestures. Now we've shown that the same appears to apply to laughter, too--at least at the level of the brain."

The positive approach

Scott and her fellow researchers played a series of sounds to volunteers and measured the responses in their brain with an fMRI scanner. Some sounds, like laughter or a triumphant shout, were positive, while others, like screaming or retching, were negative.

All of the sounds triggered responses in the premotor cortical region of the brain, which prepares the muscles in the face to move in a way that corresponds to the sound .

The response was much higher for positive sounds, suggesting they are more contagious than negative sounds--which could explain our involuntary smiles when we see people laughing.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team also tested the movement of facial muscles when the sounds were played and found that people tended to smile when they heard laughter, but didn't make a gagging face when they heard retching sounds, Scott told LiveScience . She attributes this response to the desire to avoid negative emotions and sounds.

Older than language?

The contagiousness of positive emotions could be an important social factor, according to Scott. Some scientists think human ancestors may have laughed in groups before they could speak and that laughter may have been a precursor to language.

"We usually encounter positive emotions, such as laughter or cheering, in group situations, whether watching a comedy program with family or a football game with friends," Scott said. "This response in the brain, automatically priming us to smile or laugh, provides a way or mirroring the behavior of others, something which helps us interact socially. It could play an important role in building strong bonds between individuals in a group."

Scott and her team will be studying these emotional responses in the brain in people with autism, who have "general failures of social and emotional processing" to better understand the disease and why those with it don't mirror others emotions , she said.

- No Joke: Animals Laugh, Too

- Don't Laugh: Just Think About It

- Not Funny, But LOL Anyway

- Scientists Say Everyone Can Read Minds

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Forgetting may provide a surprising evolutionary benefit, experts say

These 3 neurons may underlie the drive to eat food

Teeny tardigrades can survive space and lethal radiation. Scientists may finally know how.

Most Popular

- 2 12,000-year-old, doughnut-shaped pebbles may be early evidence of the wheel

- 3 An asteroid hit Earth just hours after being detected. It was the 3rd 'imminent impactor' of 2024

- 4 Why is Pluto not considered a planet?

- 5 24 brain networks kick in when you watch movies, study finds

IMAGES

VIDEO