An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Major transitions: how college students interpret the process of changing fields of study

Blake r silver.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2023 Apr 28.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted research re-use and secondary analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic.

Selecting a major is one of the most consequential decisions a student will make in college. Though major selection is often conceived of as a discrete choice made at a particular point in time, many students change their majors at least once during college. This article examines the process of changing majors as a key education transition. Drawing from 38 interviews with college students at a public university in the USA who changed their declared major, this study explores the ways they make meaning of transitions between fields of study. Specifically, I ask: How do students describe their experiences navigating the process of switching college majors? Six themes emerged in relation to three phases of transition: endings, neutral zones, and new beginnings. These themes provide new understandings of students’ meaning making about their experiences moving between majors. In doing so, this study (1) demonstrates the value of studying major change as an important educational transition and (2) sheds light on the potential for employing theories of transition to understand non-normative and non-linear transitions in higher education. Implications for higher education research and practice are discussed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10734-023-01050-8.

Keywords: Major, Field of study, Transition, Meaning making

Selecting a major is one of the most consequential decisions students make in college. It impacts persistence, skills acquisition, network development, and post-graduation outcomes (Arum & Roksa, 2014 ; Mcdossi, 2022 ; St John et al., 2004 ). Despite its significance, major selection is often conceived of as a discrete choice that students make at a particular point in time (Musoba et al., 2018 ). Yet research shows that one-third of students who begin a bachelor’s degree change majors at least once during college (Leu, 2017 ). Such an insight calls for a more complex understanding of students’ experiences moving between fields of study. This article examines the process of changing majors as a key education transition (Anderson et al., 2022 ).

One way to develop knowledge about educational transitions is by exploring students’ perceptions, interpretations, and meaning making about these moments of change (Perez, 2016 ; Schlossberg, 1981 ). By gathering firsthand accounts of transition, scholars have expanded understandings of how students experience the first year of college (Baxter Magolda et al., 2012 ), transfers between institutions (Allen et al., 2014 ), re-enrollment after time away from college (Rumann & Hamrick, 2010 ), and the senior-year transition to postbaccalaureate life (Kalaivanan et al., 2022 ; Silver & Roksa, 2017 ), among others.

These studies have made significant progress in building knowledge about what educational transitions look and feel like from the perspectives of students. Yet transitions between majors have been neglected in this literature. When major change is explored, it is often studied quantitatively in ways that isolate components of the process. For instance, research examines students’ reasons for leaving specific majors (Drysdale et al., 2015 ) and outcomes related to retention and major segregation (George-Jackson, 2011 ; Riegle-Crumb et al., 2016 ). Although these studies underscore the prevalence and significance of major change, they also leave questions about the broader transition between fields of study unanswered.

Drawing from 38 interviews with college students who changed their declared major at a public university in the USA, this study explores the ways they make meaning of transitions between fields of study. Specifically, I ask: How do students describe their experiences navigating the process of switching college majors? Six themes emerged in relation to Bridges ( 2004 ) three phases of transition: endings, neutral zones, and new beginnings. These themes provide new understandings of students’ experiences moving between majors. In doing so, this study (1) demonstrates the value of studying major change as an important educational transition and (2) sheds light on the potential for employing theories of transition to understand non-normative and non-linear transitions in higher education. Implications for higher education research and practice are discussed.

Studying educational transitions

Over the past two decades, scholars have learned a great deal about how students interpret and make meaning of their experiences navigating transitions in higher education (Hunter et al., 2012; Tett et al., 2017 ). This knowledge developed primarily through studies of the first-year transition into college, transfers between institutions, re-enrollment, and the senior-year transition out of college (Foote et al., 2013 ). By exploring these periods of change in the lives of college students, scholars unearthed numerous important insights, demonstrating the value of inquiry that centers student voices.

First, studies of meaning making about educational transitions helped build awareness of what transitions look like and feel like from the perspectives of students and how they come to interpret their significance (Trautwein & Bosse, 2017 ; Williams & Roberts, 2022 ). These studies document the hopes and aspirations students attach to transitions (Allen & Zhang, 2016 ; Skipper, 2012), as well as how concerns are shaped by perceptions of the context surrounding a transition (Kortegast & Yount, 2016 ). Listening to students’ accounts of transitions illuminates the factors shaping feelings of belonging, inclusion, isolation, or marginalization (Guyotte et al., 2021 ; Lange et al., 2021 ).

Second, researchers have revealed the social psychological processes that influence how students interpret and reinterpret identity during transitions. In their study of veteran students’ re-enrollment after deployment, Rumann and Hamrick ( 2010 ) showed how educational transitions sometimes involve redefining one’s sense of self (see also, Garcia & Yao, 2019 ; Williams & Roberts, 2022 ). These experiences of coming to understand identity in new ways are frequently linked to theories of self-authorship (Perez, 2016 ), and they expose how students’ meaning making about educational transitions is informed by perceptions of external influences, available resources, and one’s sense of self (Bettencourt, 2020 ; Nguyen et al., 2022 ).

Third, examining how students describe educational transitions can expand knowledge about factors that guide decisions and inform strategies. In a study of transitions to graduate school, Perez ( 2016 ) showed that attention to students’ perceptions, interpretations, and meaning making about their experiences can uncover how important decisions are made in these transitory moments. Others highlight how meaning making informs specific transition strategies (Silver & Roksa, 2017 ). Students make decisions and deploy strategies in relation to perceptions of transitions and their significance (Anderson et al., 2022 ).

This literature has made important strides in illuminating the ways students make meaning of educational transitions. Yet, as these examples show, when studying transitions in higher education, there is a tendency to focus on the process of entering or leaving institutions (Foote et al., 2013 ). This is in part because movement to and from different educational settings constitutes an important juncture in students’ broader educational journeys, where scholars show that important challenges and opportunities arise (Hunter et al., 2012; Smith & Khawaja, 2011 ). Recently however, there have been calls to pay greater attention to educational transitions within colleges and universities (Tett et al., 2017 ). For instance, scholars have studied the sophomore-year transition as students move from their first to second year of study within the same institution (Schreiner et al., 2018 ). I argue that it is likewise important to recognize the significance of transitions between college majors.

Choosing and changing majors

Neglect of transitions between fields of study stems from the way selection of majors is often conceived of as a discrete, one-time choice (Musoba et al., 2018 ). Nonetheless, scholars have begun to recognize the unique challenges of choosing a major and the need for support during this process (Fouad et al., 2016 ). Studies of major selection examine factors that lead students to declare fields of study. For instance, Allen and Zhang ( 2016 ) found that students described becoming engineering majors due to factors like job prestige, personal interests, career aspirations, and goals for further education. Other scholars document challenges students confront when choosing a major, especially obstacles related to accessing information, academic preparation, and other prerequisites for specific fields (Musoba et al., 2018 ).

Studies examining the topic of changing majors after a student has declared an initial major are primarily quantitative, documenting the frequency of switching fields of study or factors that prompt students to declare a new major (Drysdale et al., 2015 ; Pu et al., 2021 ; Riegle-Crumb et al., 2016 ). Analyzing data from a panel study of German students, Meyer et al. ( 2022 ) found that factors like prior academic achievement, career goals, and social expectations impacted whether students changed majors. Likewise, Trout ( 2021 ) used a survey to examine whether students intended to change majors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies in this vein demonstrate that switching majors impacts time-to-degree, delaying graduation for some students (George-Jackson, 2011 ).

A smaller number of studies qualitatively explore students’ experiences leaving specific college majors (Brent et al., 2019 ). Milsom and Coughlin ( 2015 ) drew from interview data to explain how some students came to feel dissatisfied with their majors, and Halasz and Bloom ( 2019 ) examined the resources students found helpful when leaving fields with GPA or test-score requirements. While these scholars are breaking new ground, a challenge with this research is that it isolates specific components of changing majors (i.e., reasons for leaving a major or access to resources), rather than exploring the broader process of transition.

Theoretical framework

To explore major change as an educational transition, this study relied on Schlossberg’s (1981) transition model. This theoretical framework has proven valuable for scholars of higher education who seek to understand how students experience moments of change in their educational journeys (McTier et al., 2017 ). This theory is especially useful for studies examining the social psychology of educational transitions as students make meaning of these experiences. While Schlossberg’s (1981) theory was initially developed to understand a broad range of life transitions, including career change or job loss, within higher education, her work has been employed more narrowly to study a small number of normative and linear transitions such as the first-year transition (Griffin & Gilbert, 2015 ; Huerta & Fishman, 2014 ), vertical transfers between two- and four-year institutions (Allen et al., 2014 ), and the senior-year transition (Silver & Roksa, 2017 ). Normative transitions are those that fit standards set by postsecondary institutions about how typical progress through higher education should unfold, and linear transitions are those required for timely progress toward completing a bachelor’s degree. By contrast, transitions that are non-normative and non-linear—like changing majors—have yet to be examined with Schlossberg’s theoretical framework.

Schlossberg’s model highlights a set of factors known as “the 4 S’s” that shape how individuals experience transitions (Anderson et al., 2022 ). The first, situation , refers to specific features of the transition like its timing, key events, and how the transition is perceived. Second, self includes facets of internal resources and identity, including psychological traits and one’s sense of self. Third, support encompasses external sources of assistance from family, mentors, and peers. Finally, the fourth S, strategies , can be observed in an individual’s approaches to managing a transition. Attention to each factor can support a comprehensive understanding of students’ experiences during an educational transition.

The purpose of this study was to understand how students describe experiences navigating the process of switching college majors. Studies of students’ perceptions and meaning making regarding experiences take a range of forms (Duran, 2021 ). Some scholars rely on narrative inquiry (Foste & Jones, 2020 ), while others use case study methods (Jones et al., 2012 ). I follow scholars who have employed a basic interpretive qualitative approach (Nguyen et al., 2022 ), which is ideal for studies seeking to understand how participants attribute meaning to their experiences (Merriam & Grenier, 2019 ). This project analyzes in-depth interviews with college students who changed majors.

Research site and participant recruitment

Data was collected at a large research university in the USA, where nearly 40,000 students were enrolled. The university offered approximately 80 majors for students pursuing a bachelor’s degree. Additionally, the institution provided resources for students selecting a major, including academic advisors, student success coaches, and career counselors. These services were organized in accordance with an “administration-centered model,” where resources were offered on an optional basis through offices that functioned as distinct entities with little coordination across units (Manning et al., 2006).

Participants were recruited through outreach to undergraduate email lists, where the call was shared with a range of programs, organizations, and academic departments to achieve diverse representation of majors. Student in their second year of study or beyond were eligible to take part in a broader research project on journeys through college. At the time of this study, there were approximately 21,000 sophomores, juniors, and seniors pursuing bachelor’s degrees at the university, and 104 of them took part in an interview. A subset of 38 students who moved from one declared field to another at least once after beginning a bachelor’s degree were included in the analysis for this study. These participants represented 20 different initial majors and 26 different destination majors. Students received a pseudonym to support confidentiality and a gift card incentive.

Data collection

Each participant completed a semi-structured, in-depth interview. Such interviews are well-suited for eliciting meaning making about experiences (Baxter Magolda & King, 2007 ; Bettencourt, 2020 ). In line with Schlossberg’s (1981) theoretical framework, questions were designed to explore each of the 4 Ss. For instance, the interview guide covered topics related to students’ sense of self and their perceptions of the situations surrounding changing majors, as well as sources of support and related strategies to navigate change. Interviews lasted 75 minutes on average and were conducted by the author (who interviewed 20 of the students) and three paid research assistants (who interviewed the remaining 18). Participants were diverse in terms of racial/ethnic identity, gender identity, parental education, and field of study (see Table 1 in the online appendix).

Data analysis

Data analysis began with efforts to develop broad familiarity with the interviews, as I listened to audio files and read interview transcripts (Saldaña, 2021 ). Following this global review of the data, I conducted line-by-line open coding in Dedoose electronic coding software, attaching descriptors that captured concepts observed through participants’ words (Corbin & Strauss, 2008 ). After transcripts were coded, analytic memos were used to examine coded excerpts for emergent themes (Emerson et al., 2011 ). This inductive process unearthed themes that were organized chronologically to illuminate students’ meaning making about the process of transitioning from one major to another. This chronological organization follows Bridges ( 2004 ) three phases of transitions, namely endings , neutral zones , and new beginnings .

Trustworthiness and positionality

Strategies were used to support the trustworthiness of this research. Peer debriefing with colleagues from my writing group proved to be especially valuable (Merriam & Grenier, 2019 ). Additionally, I present themes illustrated with direct quotes from participants and relevant context, allowing readers to evaluate my interpretation of the data. Moreover, I spent time reflecting on my positionality as a researcher and the way my social location shaped my interpretation of the data. This involved ongoing consideration of the ways my social location as a White man from a middle-class family influenced my perspectives. Given the role of academic identities and disciplinary affiliations in this project, I spent time thinking about my positionality as a faculty member and how it might differ from those of the study participants. In my roles as a teacher and mentor, I sometimes provide general advising for students considering changing majors, but my experience with this type of advising is limited to a small number of cases. My firsthand experience changing majors when I was an undergraduate—from global affairs to English literature—informed a degree of familiarity with the experiences described in this study. Nonetheless, it was crucial to be attentive to multiple perspectives, remaining conscious of the fact that students experience this transition in very different ways. Reflexive journaling throughout the analytical process supported this goal (Janesick, 2007 ).

Six themes emerged in relation to three phases of transition: endings , neutral zones , and new beginnings (Bridges, 2004 ). Two of the themes related to the endings stage of transition, where students shared their perceptions of self (as having or lacking major-relevant skills) and interpretations of their initial major (as inadequate in some way). Next, there were three themes linked to the neutral zone. Here students described tentative exploration of their new major, some of the stressors that arose between majors, and a related gap in support. The final theme spoke to students’ experiences of new beginnings as they made meaning of their adjustment to a new field of study. These themes provide new understandings of students’ meaning making about experiences transitioning between fields and illustrate the value of Schlossberg’s framework for understanding non-normative and non-linear transitions like the process of changing majors.

Endings: confidence, doubt, and reevaluating majors

When students discussed their decision to embark on a transition from one major to another, they often described their capacities or skills as incompatible with their previous major. Many came to perceive that they were not a fit for their initial field of study and its corresponding career options. In some cases, this theme was observed in the words of students who described how increasing self-confidence led them to pursue a major where they had previously believed they could not succeed. For example, Carter recalled changing his major from exercise science to community health when he became more confident in his ability to go to medical school and become a physician:

I had declared my major initially as an exercise science major… beginning my spring semester, I switched from exercise science to community health, so I could pick pre-med [track]… I started doing anatomy and physiology – I loved it, I thought I was so good, and I knew immediately, I wanted to take that even further and go for the medical degree… I raised the bar for myself.

Though he described himself as someone who previously would “second guess myself,” a new sense of confidence in his abilities, following his success in anatomy and physiology, initiated Carter’s decision to change majors.

In contrast to Carter’s description of increasing self-confidence, other students disclosed that their decisions to switch fields of study were sparked by self-doubt and concerns about their ability to succeed in previous majors. They saw themselves as unprepared or missing important skills for their initial field. For instance, Jamelle said:

[W]hen I first got here, I originally was a business major with a concentration in marketing, but I realized that there was going to be math involved, and I’m not good at math at all. So, I decided to choose communication, specifically, in public relations. I know I am good at speech and I’m good at conveying ideas, but I know I do need a lot of work in that, so I decided to choose public relations.

As this quote shows, Jamelle interpreted the fit between majors and skills in ways that informed his decision to switch majors. Seeing himself as someone who was “not good at math at all” but “good at conveying ideas,” he decided it made sense to leave the business marketing program and declare a new major in communication.

Jamelle’s sense of himself as someone who lacked proficiency in math and science was shared by other students, including Krista who professed, “I can’t do math for the life of me,” and Priya, who recalled, “biology and chemistry was the place I had difficulty with [my previous major].” Both of them switched from majors with extensive science and quantitative reasoning requirements to fields where such requirements were minimal. Other students interpreted struggles with reading and writing as signs that they were unprepared for a specific major. Josefina, for instance, explained her decision to leave the English major: “I found out that for an English major, it’s a lot of reading and a lot of writing … and just a lot of grammar.” Wary of these academic emphases, she declared a new major in anthropology.

Endings: interpreting previous majors as inadequate

A second theme related to departure from an initial field of study was observed among students who came to perceive their previous major as inadequate for their needs or ineffective at fostering student success. They described how discovering another program that appeared to provide greater support prompted efforts to declare a new major. Brooke recalled:

I think I was so inclined to switch over [to history] because I felt they were so much more organized than the English department. No shade on the English department, but just how everything was planned out [in history] was great. They have a sheet, and they’re like, “Take this class, take this class,” and their advisor is really knowledgeable on who taught which classes and what their background was… I guess that provoked me to switch. The English department’s a bit more disorganized.

Emphasizing her preference for a well-organized major with a knowledgeable advisor, Brooke described how these perceptions of the English and history departments sparked her decision to switch majors. She interpreted signals from these programs as evidence that informed her sense of fit (or lack thereof) in each field.

Ron described how similar perceptions inspired his decision to change from international affairs to communications.

It was just a different vibe. [In international affairs] I had to schedule an appointment and email people, and I didn’t exactly know who my advisor was, or who I would be meeting with every time I went to see international affairs. But I know exactly who I’m talking to, and exactly who to go to for what at communications… That’s just part of what I want in a school… You feel more like they’re there to help.

While Ron found the communications program to be more welcoming, he felt marginal in international affairs, recalling how “There’s almost a bureaucracy to a major or a field of study when it’s that big and that broad. So, that’s what I wanted to avoid as much as I could.” Likewise, Javi justified switching his major from engineering where “I wasn’t really learning much… and some of my professors really just threw out the material” to neuroscience where he described his experiences as more positive. Brooke, Ron, and Javi interpreted these signals as evidence of whether a program was committed to student success.

Neutral zones: tentative exploration of a new major

Having come to perceive misalignment between themselves—in terms of their goals, capacities, and needs—and their previous major, students described embarking on tentative exploration of new majors. As they entered the neutral zone of this educational transition (Bridges, 2004 ), many participants began exploring department websites, program requirements, and course catalogs. Priya shared that:

[W]hen I wanted to switch, I looked over the catalog for all the majors, and I looked at what classes I would have to take, and that was just the beginning. I took a specific class that was under the international affairs department – an [international conflict] class. And that class I really enjoyed… so once I looked at the department, and the classes that were required for that major, I felt like, “Okay, these are the classes that I would enjoy.”

An initial assessment of program requirements helped students like Priya determine the feasibility of changing their field of study.

These tentative evaluations of new majors often began with considering program requirements, and as Priya illustrated, they often continued when students took classes in a new field of study to probe that major. May described a similar process moving from exercise science to management:

I started looking at the program. I started looking at the classes, and I took a semester’s worth before I switched my major officially… I really enjoyed what I was learning. It was really interesting. It was definitely something I could apply to real life, so I was like, “I think that’s what I want to do.” It’s definitely more inclusive, so I can do many things with it. I was like, “I’m just going to change it.”

Similarly, Emilia recalled, “So, my first semester of my freshman year, I did exercise science, and it was not really my thing. And then I kind of took a semester, and I took a couple psychology courses, along with other classes that I needed. I really started to get into it.”

Part of exploring a new major involved notifying family and friends of the potential change to monitor their reactions. Some students described finding additional support and encouragement in this process. Terrie recalled telling her mother about plans to switch majors:

She helps me in the sense of feeling on track, but also helping me not feel as stressed about certain things, because she’ll tell me things like, “if you change your major, it’s okay. You can change it multiple times. I’ve known people who’ve done it multiple times.” So, it makes me feel more at ease.

Michelle recalled how her sister offered comparable support: “I definitely asked her about like, ‘Oh, what do you think about this major? What do you think about that major?’ We will call it my quarter-life crisis about choosing a major.” Though this decision was difficult, Michelle claimed talking with her sister helped.

When some students floated the idea of a major change to their families, they received hesitation. Ben, for instance, described discussions with his parents: “They were a little upset, because they really loved bioengineering.” Nonetheless, he found they were receptive of his proposed change: “But also, my parents just are so amazing. They’re super supportive … honestly, they didn’t really care what major. It could be business, it could be communications, for all they care. They just would want me to be happy.” Once students perceived that their family and friends supported a change, it often seemed feasible to move forward.

Neutral zones: stressors of liminality

A fourth theme appeared in students’ descriptions of the emotional experience of the neutral zone. Zara summed up her feelings as she recalled, “It was terrifying, of course. As a freshman, wanting to switch your major right away is terrifying.” Students articulated that being between majors evoked anxiety. Minh described navigating this change as “the biggest moment of uncertainty” in her college career:

I was trying to scramble to find something new… I was very scared during that time just because I’m the type of person who always likes to have things planned out… I didn’t know what specific outcome I was going to have, so I was struggling a little bit to stay motivated, because I was just really scared and trying to figure out what it was exactly that I wanted to do.

Other students echoed Minh’s claims about the uncertainty of this moment. Nicholas recalled deciding to leave the health administration program before determining his next major:

I was trying to figure out exactly what I wanted to do here at [the university]. I wasn’t sure which road to take … during that time period, I just wasn’t sure exactly what I should do. That was the most uncertain time I had, truly … that just felt like I had the weight of the world on my shoulders, because I felt like at the end I needed to pick something. I knew I needed to pick a field to go down, because I was concerned about not being able to graduate within four years.

His worries about this transition were especially troubling, “because for me having a plan set in place is very secure feeling.” Without a plan, Nicholas struggled between majors.

As students worked through changing majors, they discussed concerns about whether they were navigating this process effectively. Naya agreed with Minh’s assessment that the transition evoked feelings of uncertainty: “Changing your major is a very uncertain time in your life. You’re like, ‘am I doing the right thing? Am I on the right path to where I want to be?’” The questions Naya raised were shared by May: “‘Is this going to be good for me? Am I actually going to finish this? Will it work out in the end?’ It was a big, bold move for me... I was very concerned that it wouldn’t work out.” Grappling with these questions was challenging in many respects.

Neutral zones: perceiving a support gap

As students moved to declare a new major, many described perceiving a gap in what they needed from the university and the support they actually received. For some participants, the absence of support was felt when faculty and staff failed to recognize the emotional weight of this transition. Olive recalled her frustrations that she was simply directed to complete forms when seeking help:

I just emailed the advising [staff] … and they were just like “fill this form; you can do it.” And I was like “okay,” and I printed it out… My neuroscience advisor was like “oh, sorry to see you go, here are the forms,” … and with the psychology department, same thing.

While advisors in both departments encouraged Olive to fill out a change of major form, she was disheartened that neither took time to acknowledge the significance of this transition or offer more substantial support. “But in terms of the actual thought process… that is like a career path change… I think there definitely could have been a little bit more support.”

Other students described similar challenges finding support transitioning between majors. Priya, for instance, said:

I think [the university] should do a little more in helping students determine what their [major will be] … it’s a huge difference switching majors – moving from neuroscience to international affairs… I think [the university] could do a little more in helping students do that. I don’t know if they have non-major academic advisors, because academic advisors in specific fields, they’re going to try to get you to go into their field. So, there needs to be an opportunity where if I’m unsure, there should just be a department where you can go with “okay I’m unsure what I want to do, could you help me?”

Priya’s quote illustrates not only her desire for more support in the transition between majors, but also her sense that advisors working for a single program may not be best equipped to help students navigate such a change. Corey likewise recalled feeling overwhelmed when “I was in limbo with advisors,” after deciding to leave the music major but before officially becoming an English major: “I also remember feeling a lot of anxiety, because in my mind the fact that some things are difficult right now must be signaling I’m maybe not cut out for college or that I’m so disorganized that I’m not going to be successful in a career.”

While the university offered advising for undeclared students, most participants perceived that this resource was not intended for individuals who were switching from one declared major to another. Responding to what they interpreted as a gap in support, many students turned to self-directed research. For instance, Javi recalled “I went around websites, like, Reddit, Google, and other stuff… and then I just gathered up the information.”

New beginnings: adjusting to a new major

Once the switch to a new major was official, students made meaning of the broader change in ways that illuminated their experiences adjusting to these fields of study. For some students, new beginnings in their destination major provided reassurance. Josefina recalled the aftermath of declaring her new field of study:

I chose anthropology… I love learning about people, and I love learning about their different stories and their history and their mythologies and all that… This encompasses all the things that I’m interested in. And when we’re talking about literature or history or mythology, or cultures and religions, and stuff like that, I just feel like it was the perfect thing.

Similarly, May claimed, “I feel like in the end it did work out really well,” and Becca reflected, “I started taking those classes. Then, I really started liking learning about the environment. It was right, so I stuck with it.”

For many students though, adjustment to a new major was not as smooth. Participants described lingering doubts and concerns. Keith noted that he recently considered changing back to his original major: “I thought about if maybe international affairs wasn’t for me, and I thought about going back to information technology. But then, I was like ‘no,’ because of my original ideas about why it’s not beneficial for me. I decided just to stick with what I’m doing now.” Yasmine shared a comparable perspective: “I’m happy with my choice that I’ve changed majors. At times, it can be challenging, and I do doubt that I’m in the correct major for me, because I do have other interests. But ultimately, I’m happy with my choice.”

For some students, lingering doubts led them to leave open the possibility of changing majors again in the future. Minh provided an example when she reported:

I definitely feel scared and worried whenever I start feeling uncertain about [my new major], because my classes are starting to get hard… if I can’t get through this class, then that’s probably a sign that I shouldn’t go into [this major]. So, I’ll try my best to get through it. If I can’t, then I can switch majors.

Even as she settled into her new program in accounting, Minh remained open to signs that she might need to change majors again.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper examined in-depth interviews to understand how students experience the process of changing majors. In contrast to typical conceptions of major selection as a discrete decision, presented findings illuminate the value of examining major change as an important educational transition. Six themes emerged in relation to the endings, neutral zones, and new beginnings involved in this transition (Bridges, 2004 ). Examining these themes through Schlossberg’s (1981) theoretical framework supports my argument for studying major change as an educational transition. Presented findings complement and extend previous scholarship on educational transitions and major selection. The findings also present a road map for expanding the use of Schlossberg’s work to understand previously neglected educational transitions.

In relation to the first theme, the finding that students’ experiences with self-doubt sparked decisions to change majors aligns with research showing that critical self-assessments can prompt students to leave a major (Meyer et al., 2022 ). Yet, the parallel finding that building self-confidence could likewise instigate transition to a new major extends this work. As some students built greater self-confidence, they became open to the possibility that they could succeed in a major previously assumed to be too challenging. A limitation of the present study is its inability to speak to sociodemographic variation in students’ meaning making. Racial, gender, and socioeconomic inequality in experiences within various majors are well documented (DiPrete & Buchmann, 2013 ; Rainey et al., 2018 ). For instance, myriad studies show how chilly climates in STEM fields can undermine the confidence of women and students of color (Brent et al., 2019 ; Riegle-Crumb et al., 2016 ). Future research could benefit from examining how the intersections of race, gender, and socioeconomic status may shape how students develop and respond to increased self-confidence.

The second theme illustrated how students came to perceive their initial major as inadequate for meeting their needs and fostering success, adding nuance to understandings of factors that spark interest in changing majors. While career goals, GPA requirements, and other previously documented factors clearly played a role (Pu et al. 2021 ; Meyer et al., 2022 ), students’ meaning making about the support and resources available through various majors was likewise influential. Schlossberg ( 1981 ) articulated the importance of support for successfully navigating a transition once it is underway; this finding illustrates the ways support (or a lack thereof) can also spark a transition. This observation deserves further consideration in higher education scholarship where movement between settings (e.g., student organizations, offices, and courses) in a college or university is often understood as driven by student characteristics like familiarity with college environments (Guyotte et al., 2021 ; Lange et al., 2021 ). In this case by contrast, features of departments also provoked movement between majors.

An important strategy for navigating the process of switching majors emerged in the third theme, where students described tentatively exploring a new major to assess its feasibility. While strategies , one of Schlossberg’s 4Ss, have received abundant attention in research on educational transitions (Anderson et al., 2022 ), this type of tentative exploration has not previously been documented in higher education research. Typical emphases on entering and leaving institutions provide limited opportunity for such exploration (Foote et al. 2013 ). Within-institution transitions, by contrast, offer possibilities for more readily testing various opportunities before committing to a destination. Such a finding raises questions about the impact of this strategy for progress toward graduation. How does taking classes in new fields impact students’ progress toward a degree? And what happens to students who decide not to change majors? Will extra credits fill elective requirements or delay graduation?

Theme four exposed unique stressors involved in navigating the liminal space between fields. By departing from studying major change as a discrete choice (Musoba et al., 2018 ), this study illuminates the complex emotions involved in navigating the neutral zone of changing majors (Bridges, 2004 ). Though participants described looking forward to entering new fields, they also articulated the ways change evoked anxiety. It was in relation to these stressors that students came to perceive the support gap articulated in the fifth theme. Scholars should remain attentive to variation in perceptions of access to support (Schlossberg’s 1981 ). Research has shown that students of color, women, first-generation students, and students with other minoritized identities often encounter marginalization that can limit support (Rincón & George-Jackson, 2016 ; Mcdossi, 2022 ; Miller et al., 2021 ). Future studies of resources for major change could examine intersectional variation in perceptions of resource availability and utilization (Duran, 2021 ).

In addition to implications for scholarship, the fourth and fifth themes have implications for practice in higher education. Resources for students in transition have made important advances in scaffolding other educational transitions (Foote et al., 2013 ). Comparable resources could be beneficial for students changing majors. For instance, students in this study observed that advisors directed them to the correct forms to initiate changing majors. Yet, they often desired more detailed guidance regarding the broader implications of this transition—guidance that could be provided by advisors, career counselors, and other faculty and staff.

Students made meaning of their process of adjustment to a new field in theme six. While some described affirmation and reassurance, others acknowledged lingering doubts and remained open to changing majors yet again. This finding complicates prior research on the outcomes of major change, which has focused on topics like the impact on time-to-degree (George-Jackson, 2011 ). Future research could extend this work by exploring factors influencing students’ experiences in their destination major and the experiences of students who change majors multiple times.

This final theme sheds light on additional possibilities for fostering support. Given the complexity involved in adjusting to a new field, students may benefit from tailored programs for individuals who change majors. First-year seminars present a model for curricular scaffolding to support educational transitions (Young & Keup, 2016 ). While the timing of switching a major may not coincide neatly with a semester, research shows that shorter duration bridge programs nurture career aspirations in the transition to college (Kitchen et al., 2018 ). Similar courses or programs could help students transition between fields of study (see also Fouad et al., 2016 ). Navigating this process with major-specific learning objectives and a cohort of peers could address the gaps in support identified by participants (Williams & Roberts, 2022 ).

Collectively, this study’s findings demonstrate the promise of applying Schlossberg’s theory to new types of educational transitions. Though Schlossberg ( 1981 ) initially envisioned her work as applicable to a variety of life changes—both planned and unplanned—studies in higher education have examined the 4Ss primarily to study transitions that are normative (e.g., the first-year, sophomore, and senior-year transitions) and/or linear (e.g., reenrollment or vertical transfers from a two- to a four-year institution). Though approximately one-third of students transition between fields (Leu, 2017 ), participants in this study underscored the myriad ways changing majors is not treated as a normative transition. Likewise, such change is rarely linear; students illustrated this point as they described having to prolong their studies due to changing majors. Future research in higher education may benefit from employing similar theoretical frameworks to study other types of non-normative and non-linear transitions like college stop-out, horizontal or reverse transfers, and transitions to/from focused career tracks (e.g., pre-medical or pre-law). Building knowledge about the diverse pathways students traverse through college represents an important step in providing more effective support for student success.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 24 kb)

Declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no competing interests.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Allen TO, Zhang Y. Dedicated to their degrees: Adult transfer students in engineering baccalaureate programs. Community College Review. 2016;44(1):70–86. doi: 10.1177/0091552115617018. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen JM, Smith CL, Muehleck JK. Pre-and post-transfer academic advising: What students say are the similarities and differences. Journal of College Student Development. 2014;55(4):353–367. doi: 10.1353/csd.2014.0034. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson ML, Goodman J, Schlossberg NK. Counseling adults in transition: Linking Schlossberg’s theory with practice in a diverse world. 5. Springer; 2022. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arum R, Roksa J. Aspiring adults adrift: Tentative transitions of college graduates. University of Chicago Press; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baxter Magolda MB, King PM. Interview strategies for assessing self-authorship: Constructing conversations to assess meaning making. Journal of College Student Development. 2007;48(5):491–508. doi: 10.1353/csd.2007.0055. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baxter Magolda MB, King PM, Taylor KB, Wakefield KM. Decreasing authority dependence during the first year of college. Journal of College Student Development. 2012;53(3):418–435. doi: 10.1353/csd.2012.0040. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bettencourt GM. “When I think about working class, I think about people that work for what they have”: How working-class students engage in meaning making about their social class identity. Journal of College Student Development. 2020;61(2):154–170. doi: 10.1353/csd.2020.0015. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brent R, Mobley C, Brawner CE, Orr MK. In 2019 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference. IEEE; 2019. “I feel like I’ve found where I belong.” Interviews with Black engineering students who change majors; pp. 1–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bridges W. Transitions: Making sense of life’s changes. 2. Addison-Wesley; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. The basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- DiPrete TA, Buchmann C. The rise of women. Russell Sage Foundation; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Drysdale MT, Frost N, Mcbeath ML. How often do they change their minds and does work-integrated learning play a role? Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education. 2015;16(2):145–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duran A. Intersectional perspectives on meaning-making influences: Theoretical insights from research centering queer students of color. Journal of College Student Development. 2021;62(4):438–454. doi: 10.1353/csd.2021.0046. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Foote SM, Hinkle SE, Kranzow J, Pistilli MD, Rease Miles L, Simon JG. College students in transition. University of South Carolina; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Foste Z, Jones SR. Narrating whiteness: A qualitative exploration of how white college students construct and give meaning to their racial location. Journal of College Student Development. 2020;61(2):171–188. doi: 10.1353/csd.2020.0016. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fouad NA, Ghosh A, Chang WH, Figueiredo C, Bachhuber T. Career exploration among college students. Journal of College Student Development. 2016;57(4):460. doi: 10.1353/csd.2016.0047. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia CE, Yao CW. The role of an online first-year seminar in higher education doctoral students’ scholarly development. The Internet and Higher Education. 2019;42:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.04.002. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- George-Jackson C. STEM switching: Examining departures of undergraduate women in STEM fields. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering. 2011;17(2):149–171. doi: 10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.2011002912. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Griffin KA, Gilbert CK. Better transitions for troops: An application of Schlossberg's transition framework to analyses of barriers and institutional support structures for student veterans. The Journal of Higher Education. 2015;86(1):71–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guyotte KW, Flint MA, Latopolski KS. Cartographies of belonging: Mapping nomadic narratives of first-year students. Critical Studies in Education. 2021;62(5):543–558. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2019.1657160. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Halasz HM, Bloom JL. Major adjustment: Undergraduates’ transition experiences when leaving selective degree programs. NACADA Journal. 2019;39(1):77–88. doi: 10.12930/NACADA-18-008. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huerta A, Fishman S. Marginality and mattering: Urban Latino male undergraduates in higher education. Journal of The First-Year Experience & Students in Transition. 2014;26(1):85–100. [ Google Scholar ]

- Janesick VJ. Journaling, reflexive. In: Ritzer G, editor. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Blackwell; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones SR, Rowan-Kenyon HT, Ireland SMY, Niehaus E, Skendall KC. The meaning students make as participants in short-term immersion programs. Journal of College Student Development. 2012;53(2):201–220. doi: 10.1353/csd.2012.0026. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalaivanan T, Krietzberg L, Silver BR, Kwan B. The senior-year transition: Gendered experiences of second-generation immigrant college students. Journal of Women and Gender in Higher Education. 2022;15(1):21–40. doi: 10.1080/26379112.2022.2027246. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kitchen JA, Sadler P, Sonnert G. The impact of summer bridge programs on college students’ STEM career aspirations. Journal of College Student Development. 2018;59(6):698–715. doi: 10.1353/csd.2018.0066. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kortegast C, Yount EM. Identity, family, and faith: US third culture kids transition to college. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 2016;53(2):230–242. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2016.1121148. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leu K. NCES 2018-434. National Center for Education Statistics; 2017. Beginning college students who change their majors within 3 years of enrollment: Data point. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lange AC, Linley JL, Kilgo CA. Trans students’ college choice & journeys to undergraduate education. Journal of Homosexuality. 2021;69(10):1721–1742. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2021.1921508. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mcdossi, O. (2022). Inequality reproduction, higher education, and the double major choice in college. Higher Education , 1–30.

- McTier TS, Santa-Ramirez S, McGuire KM. A prison to school pipeline: College students with criminal records and their transitions into higher education. Journal of Underrepresented & Minority Progress. 2017;1(1):8–22. doi: 10.32674/jump.v1i1.33. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Merriam SB, Grenier RS. Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyer J, Leuze K, Strauss S. Individual achievement, person-major fit, or social expectations: Why do students switch majors in German higher education? Research in Higher Education. 2022;63(2):222–247. doi: 10.1007/s11162-021-09650-y. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller RA, Vaccaro A, Kimball EW, Forester R. “It’s dude culture”: Students with minoritized identities of sexuality and/or gender navigating STEM majors. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 2021;14(3):340. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000171. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Milsom A, Coughlin J. Satisfaction with college major: A grounded theory study. The Journal of the National Academic Advising Association. 2015;35(2):5–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Musoba GD, Jones VA, Nicholas T. From open door to limited access: Transfer students and the challenges of choosing a major. Journal of College Student Development. 2018;59(6):716–733. doi: 10.1353/csd.2018.0067. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nguyen DJ, Copeland OM, Renn KA. LGBQ+ students’ college search processes: Implications for college transitions. Journal of The First-Year Experience & Students in Transition. 2022;34(1):43–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- Perez RJ. Exploring developmental differences in students’ sensemaking during the transition to graduate school. Journal of College Student Development. 2016;57(7):763–777. doi: 10.1353/csd.2016.0077. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pu S, Yan Y, Zhang L. Do Peers Affect Undergraduates’ Decisions to Switch Majors? Educational Researcher. 2021;50(8):516–526. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211023514. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rainey K, Dancy M, Mickelson R, Stearns E, Moller S. Race and gender differences in how sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education. 2018;5(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s40594-018-0115-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Riegle-Crumb C, King B, Moore C. Do they stay or do they go? The switching decisions of individuals who enter gender atypical college majors. Sex Roles. 2016;74(9):436. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0583-4. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rincón BE, George-Jackson CE. Examining department climate for women in engineering: The role of STEM interventions. Journal of College Student Development. 2016;57(6):742–747. doi: 10.1353/csd.2016.0072. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rumann CB, Hamrick FA. Student veterans in transition: Re-enrolling after war zone deployments. The Journal of Higher Education. 2010;81(4):431–458. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2010.11779060. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 4. Sage; 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schlossberg NK. A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. The Counseling Psychologist. 1981;9(2):2–18. doi: 10.1177/001100008100900202. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schreiner LA, Schaller MA, Young DG. Future directions for enhancing sophomore success. New Directions for Higher Education. 2018;183:109–112. doi: 10.1002/he.20297. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Silver BR, Roksa J. Navigating uncertainty and responsibility: Understanding inequality in the senior-year transition. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 2017;54(3):248–260. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2017.1331851. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith RA, Khawaja NG. A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011;35(6):699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- St John EP, Hu S, Simmons A, Carter DF, Weber J. What difference does a major make? The influence of college major field on persistence by African American and White students. Research in Higher Education. 2004;45(3):209–232. doi: 10.1023/B:RIHE.0000019587.46953.9d. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tett L, Cree VE, Christie H. From further to higher education: Transition as an on-going process. Higher Education. 2017;73(3):389–406. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0101-1. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Trautwein C, Bosse E. The first year in higher education—Critical requirements from the student perspective. Higher Education. 2017;73(3):371–387. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0098-5. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Trout B. Business students’ intentions to change majors amid the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice. 2021;21(7):1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams, H., & Roberts, N. (2022). ‘I just think it’s really awkward’: Transitioning to higher education and the implications for student retention. Higher Education , 1–17.

- Young DG, Keup JR. Using hybridization and specialization to enhance the first-year experience in community colleges: A national picture of high-impact practices in first-year seminars. New Directions for Community Colleges. 2016;175:57–69. doi: 10.1002/cc.20212. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (574.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Major Decision: The Impact of Major Switching on Academic Outcomes in Community Colleges

- Published: 18 September 2020

- Volume 62 , pages 498–527, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Vivian Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6170-3197 1 ,

- Soumya Mishra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7261-6224 1 &

- Elizabeth M. Kopko 1

1948 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

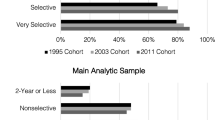

A third of the 2- and 4-year undergraduates beginning college in 2011–2012 changed their major in the first 3 years of enrollment. Yet, few studies have examined the effects of major switching on student outcomes, particularly in community colleges. Major switching can delay or impede college completion through excess credit accumulation, or it can increase the probability of completion due to a better academic match. Using state administrative data and propensity score matching, we find that major switching increases certificate completion rates but moderately decreases the probability of bachelor’s degree completion in community colleges for students who started with a declared major. We suggest that instead of discouraging major switching, institutions should integrate switching into program planning. Policies like common course-sequencing, cross-discipline introductory courses and flexible application of credits can allow students to revise their interests and goals without losing much time, credits, or tuition dollars.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

How many credits should an undergraduate take.

Margins that Matter: Exploring the Association Between Academic Match and Bachelor’s Degree Completion Over Time

Does Dual Enrollment Influence High School Graduation, College Enrollment, Choice, and Persistence?

As part of state or national initiatives, about 300 colleges are using the guided pathways model to implement whole-college redesign that emphasizes, among other things, early long-term academic planning among students (Jenkins et al. 2019 ).

Our data do not include credits earned by students who transferred to private or out-of-state 4-year universities. However, the NSC data suggests that only 5% of our sample transferred to private institutions, so we do not expect the lack of private or out-of-state 4-year data to affect our results.

Our robustness checks include an analysis including the 1000 students who started with undeclared majors, results are discussed in a later section.

A similar strategy was employed by Dadgar and Trimble ( 2015 ) and Liu et al. ( 2015 ).

To test for the robustness of our definition we also model major switching across four-digit CIP codes. Despite an increase in majors from 22 to 167, the rate of switching only increases from 23 to 27%. The results using this definition are similar to our findings in magnitude and direction (see Table A2).

See Table 1 for details on incidence of switching across majors.

For a robustness check, we run the matching model using 0.2 standard deviations and find similar results. Yet using 0.05 standard deviations gives us a closer match between treated and control observations. We also run the model using a probit instead of a logit regression in the first stage and with the Abadie and Imbens ( 2011 ) standard errors that take into account the fact that the propensity scores are estimated in separate steps. The results remain consistent.

Appendix Table A1 presents the post-match balance across treatment and control groups.

The process of propensity score matching was done within each of the ten datasets and the mean of PSM variables from all datasets were used for calculating estimated treatment effects (Cham and West 2016 ; Hill 2004 ; Mitra and Reiter 2016 ).

Literature suggests that poor performance in the first-term can increase major switching; however, these indicators may also be influenced by the initial major choice. We tested across alternate model specifications that sequentially excluded CIP, institutional effects and first-term academic performance variables. Stability of effects across these models suggests that we are matching on a robust set of variables.

We separate AA and AS degrees from AAS because AAS is considered a terminal degree and program credits earned for this degree generally are not transferable to 4-year institutions.

We define excess credits based on the most common degree requirements in the state. These average at 70 credits for associate degrees and 130 credits for bachelor’s degrees according to the state department of higher education website.

Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. W. (2011). Bias-corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 29 (1), 1–11.

Article Google Scholar

Adelman, C. (2006). The toolbox revisited: Paths to degree completion from high school through college . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Google Scholar

Alfonso, M. (2006). The impact of community college attendance on baccalaureate attainment. Research in Higher Education, 47 (8), 873–903.

Astin, A. W. (1977). Four critical years: Effects of college on beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Austin, P. C. (2011). An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46 (3), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 .

Bailey, T., Jaggars, S. S., & Jenkins, D. (2015). Redesigning America’s community colleges: A clearer path to student success . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Beggs, J. M., Bantham, J. H., & Taylor, S. (2008). Distinguishing the factors influencing college students’ choice of major. College Student Journal, 42 (2), 381–395.

Caliendo, M., & Kopeinig, S. (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22 (1), 31–72.

Cham, H., & West, S. G. (2016). Propensity score analysis with missing data. Psychological Methods, 21 (3), 427.

Chen, X. (2013). STEM attrition: College students’ paths into and out of STEM fields (NCES 2014–001) . Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Dadgar, M., & Trimble, M. J. (2015). Labor market returns to sub-baccalaureate credentials: How much does a community college degree or certificate pay? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37 (4), 399–418.

Dickson, L. (2010). Race and gender differences in college major choice. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627 (1), 108–124.

Feldman, K. A., Smart, J. C., & Ethington, C. A. (1999). Major field and person-environment fit: Using Holland’s theory to study change and stability of college students. Journal of Higher Education, 70 (6), 642–669.

Fink, J., Jenkins, D., Kopko, E., & Ran, F. X. (2018). Using data mining to explore why community college transfer students earn bachelor’s degrees with excess credits. (CCRC Working Paper No. 100). New York, NY: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center.

Foraker, M. J. (2012). Does changing majors really affect the time to graduate? The impact of changing majors on student retention, graduation, and time to graduate . Bowling Green, KY: Western Kentucky State University, Office of Institutional Research.

Gross, B., & Goldhaber, D. (2009). Community college transfer and articulation policies: Looking beneath the surface (CRPE Working Paper 2009–1). Seattle, WA: Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Hill, J. (2004). Reducing bias in treatment effect estimation in observational studies suffering from missing data. (Working Paper 04–01). New York, NY: Columbia University Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy.

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments . Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Jenkins, D. (2011). Redesigning community colleges for completion: Lessons from research on high-performance organizations (Assessment of Evidence Series Report) . New York: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center.

Jenkins, D., & Cho, S. (2012). Get with the program: Accelerating community college students’ entry into and completion of programs of study (CCRC Working Paper No. 24). New York, NY: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center.

Jenkins, D., Lahr, H., Brown, A. E., & Mazzariello, A. (2019). Redesigning your college through guided pathways: Lessons on managing whole-college reform from the AACC Pathways Project . New York: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center.

Jenkins, D., Lahr, H., & Fink, J. (2017). Implementing guided pathways: Early insights from the AACC pathways colleges . New York: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center.

Jones, L. K. (1989). Measuring a three-dimensional construct of career indecision among college students: A revision of the Vocational Decision Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36 (4), 477–486.

Karp, M. M., Hughes, K. L., & O’Gara, L. (2010). An exploration of Tinto’s integration framework for community college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 12 (1), 69–86.

Kopko, E. (2017). Essays on the economics of education: Community college pathways and student success (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Columbia Academic Commons. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8DR36TQ

Kramer, D. A., Holcomb, M. R., & Kelchen, R. (2018). The costs and consequences of excess credit hours policies. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40 (1), 3–28.

Leppel, K., Williams, M. L., & Waldauer, C. (2001). The impact of parental occupation and socioeconomic status on choice of college major. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22 (4), 373–394.

Liu, V. Y., Belfield, C. R., & Trimble, M. J. (2015). The medium-term labor market returns to community college awards: Evidence from North Carolina. Economics of Education Review, 44 , 42–55.

Ma, Y. (2009). Family socioeconomic status, parental involvement, and college major choices—gender, race/ethnic, and nativity patterns. Sociological Perspectives, 52 (2), 211–234.

Malgwi, C. A., Howe, M. A., & Burnaby, P. A. (2005). Influences on students’ choice of college major. Journal of Education for Business, 80 (5), 275–282.

Micceri, T. (1996). USF student retention: Factors influencing, transfers to other SUS institutions, and effects within colleges and majors. Phase II. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Institutional Research and Planning.

Micceri, T. (2001). Change your major and double your graduation chances. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Institutional Research, Long Beach, CA.

Mitra, R., & Reiter, J. P. (2016). A comparison of two methods of estimating propensity scores after multiple imputation. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 25 (1), 188–204.

Murphy, M. (2000). Predicting graduation: Are test score and high school performance adequate. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Institutional Research, Cincinnati, OH.

Orndorff, R. M., & Herr, E. L. (1996). A comparative study of declared and undeclared college students on career uncertainty and involvement in career development activities. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74 (6), 632–639.

Ost, B. (2010). The role of peers and grades in determining major persistence in the sciences. Economics of Education Review, 29 (6), 923–934.

Oster, E. (2016). Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 37 (2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2016.1227711 .

Porter, S. R., & Umbach, P. D. (2006). College major choice: An analysis of person–environment fit. Research in Higher Education, 47 (4), 429–449.

Scott-Clayton, J. (2011). The shapeless river: Does a lack of structure inhibit students’ progress at community colleges? (CCRC Working Paper No. 25). New York, NY: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center.

Sklar, J. (2014). The impact of change of major on time to bachelor’s degree completion with special emphasis on STEM disciplines: A multilevel discrete-time hazard modeling approach . San Luis Obispo, CA: California Polytechnic State University.

Stinebrickner, R., & Stinebrickner, T. (2014). Academic performance and college dropout: Using longitudinal expectations data to estimate a learning model. Journal of Labor Economics, 32 (3), 601–644.

Stuart, E. A. (2010). Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 25 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313 .

Terenzini, P. T., Springer, L., Yaeger, P. M., Pascarella, E. T., & Nora, A. (1996). First-generation college students: Characteristics, experiences, and cognitive development. Research in Higher Education, 37 (1), 1–22.

Trapmann, S., Hell, B., Hirn, J. O. W., & Schuler, H. (2007). Meta-analysis of the relationship between the Big Five and academic success at university. Journal of Psychology, 215 (2), 132–151.

Trusty, J., Robinson, C. R., Plata, M., & Ng, K. (2000). Effects of gender, socioeconomic status, and early academic performance on postsecondary educational choice. Journal of Counseling and Development, 78 , 463–472.

U.S. Department of Education. (2017). Data point: Beginning college students who change their majors within 3 years of enrollment . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Van Noy, M., Trimble, M., Jenkins, D., Barnett, E., & Wachen, J. (2016). Guided pathways to careers: Four dimensions of structure in community college career-technical programs. Community College Review, 44 (4), 263–285.

White, I. R., Royston, P., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30 (4), 377–399.

Wiswall, M., & Zafar, B. (2015). How do college students respond to public information about earnings? Journal of Human Capital, 9 (2), 117–169.

Yue, H., & Fu, X. (2017). Rethinking graduation and time to degree: A fresh perspective. Research in Higher Education, 58 (2), 184–213.

Zafar, B. (2013). College major choice and the gender gap. Journal of Human Resources, 48 (3), 545–595.

Zeidenberg, M. (2012). Valuable learning or “spinning their wheels”? Understanding excess credits earned by community college associate degree completers. Community College Review, 43 (2), 123–141.

Download references

Funding for this study was provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We are grateful for excellent feedback from Michelle Van Noy, Davis Jenkins, John Fink, and attendees of the 2019 Association for Education Finance Policy Annual Conference. Any errors are those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Community College Research Center, Teachers College Columbia University, New York, USA

Vivian Liu, Soumya Mishra & Elizabeth M. Kopko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Soumya Mishra .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See Tables 8 and 9 .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Liu, V., Mishra, S. & Kopko, E. Major Decision: The Impact of Major Switching on Academic Outcomes in Community Colleges. Res High Educ 62 , 498–527 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-020-09608-6

Download citation

Received : 02 August 2019

Published : 18 September 2020

Issue Date : June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-020-09608-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Major switching

- Academic outcomes

- Community colleges

- Major choice

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Beyond decisions about whether, where, at what intensity, and for how long to enroll, college students' choice of major represents another kind of postsecondary "swirl" (McCormick 2003) relevant to processes of educational stratification.While the correlates and consequences of college major selection have been studied at great length, most scholarly accounts conceptualize and measure ...

Selecting a major is one of the most consequential decisions students make in college. It impacts persistence, skills acquisition, network development, and post-graduation outcomes (Arum & Roksa, 2014; Mcdossi, 2022; St John et al., 2004).Despite its significance, major selection is often conceived of as a discrete choice that students make at a particular point in time (Musoba et al., 2018).

"There is perhaps, no college decision that is more thought-provoking, gut wrenching and rest-of-your life oriented-or disoriented-than the choice of a major." (St. John, 2000, p. 22) Choosing a college major is arguably one of the most important life decisions an individual can make. The purpose of the current study was to identify the most

Major choice is one of the most important decisions students make in college. Students in different majors take different classes that expose them to different content and, in many cases, require different amounts of critical thinking (Arum and Roksa 2011).Research also highlights the earnings differentials between individuals with bachelor's degrees in different fields of study.

navigate the college major choice or change pro-cess. Students undecided on a major are a unique and growing population. Nationally, the propor-tion of entering first-time, full-time college stu-dents in the U.S. who selected undecided as their intended college major increased from 1.7% in 1966 to 8.9% in 2015 (Eagan et al., 2016). Stu-

College Majors Arpita Patnaik, Matthew J. Wiswall, and Basit Zafar NBER Working Paper No. 27645 August 2020 JEL No. D81,D84,I21,I23,J10 ABSTRACT This article reviews the recent literature on the determinants of college major choices. We first highlight long-term trends and persistent differences in college major choices by gender, race,

In this paper, we analyzed the relationship between students' motivations for choosing academic majors and their satisfaction and sense of belonging on campus. Based on a multi-institutional survey of students who attended large, public, research universities in 2009, the results suggest that external extrinsic motivations for selecting a major tend to be negatively associated with students ...

Keywords: college majors; major orientations; inequality; higher education [End of page 46] Introduction. Choosing a college major is a critical higher education decision. College majors shape short-term outcomes such as difficulty of curriculum (Armstrong & Hamilton, 2013; Lindemann et al., 2016), skill development (Arum & Roksa, 2011), and friendship networks (Chambliss & Takacs, 2014; Raabe ...

Selecting a major is one of the most consequential decisions a student will make in college. Though major selection is often conceived of as a discrete choice made at a particular point in time, many students change their majors at least once during college. This article examines the process of changing majors as a key education transition. Drawing from 38 interviews with college students at a ...

A third of the 2- and 4-year undergraduates beginning college in 2011-2012 changed their major in the first 3 years of enrollment. Yet, few studies have examined the effects of major switching on student outcomes, particularly in community colleges. Major switching can delay or impede college completion through excess credit accumulation, or it can increase the probability of completion due ...