Help with IRB Applications for a Retrospective Chart Review

IRB Considerations for a Retrospective Chart Review

The information on this web page is designed for medical students. The purpose is to help guide students through the key steps of preparing and submitting an IRB application for a retrospective chart review. This is a quick guide and is not intended to provide guidance on formulating a research question, literature searching, data analysis, or presentation/publication of results.

What is a retrospective chart review?

A retrospective chart review is a type of clinical research study in which data is collected solely from the medical record or another patient database. As a result, there is no intervention with research subjects and no interaction with research subjects. Importantly, the medical treatment or care provided to patients who are subjects in a retrospective chart review is NOT directly related to the research study. In other words, the medical care was provided to patients regardless of whether the study was being done or not, thus the methods of a retrospective chart review are only related to identifying subjects and extracting their information from the medical record. As a result, any medical treatment, and risks/benefits thereof, have nothing to do with your study from the IRB’s perspective.

Note that a retrospective chart review is NOT a study design, rather it is a study methodology. The study design for a retrospective chart review is always observational, and can be a case series, a case control study, a cohort study, or a cross-sectional study.

A chart review can be paired with a survey or an experimental (intervention) arm of a study. This quick guide only deals with the IRB considerations for the chart review portion of the study.

How do I get access to medical records?

The first step in conducting a chart review is to have a research mentor who already has access to the medical record. It is extremely unlikely that any health system will allow a medical student to run their own chart review, and most IRBs require a principal investigator that is a physician or faculty member. Thus, to conduct a chart review, which will require access to medical records, you will need a research mentor who has access to the medical records.

What is the IRB?

The IRB is a committee of faculty, staff, and laypersons that oversees human subjects research. For the purposes of this guide, be aware that medical records are considered human subjects, as a result, retrospective chart review studies require IRB review because they are considered human subjects research.

Do chart reviews require IRB review?

Yes, chart reviews must be reviewed by the IRB if they are research. Even chart reviews that you know will fall into the EXEMPT category. Chart reviews can only be determined EXEMPT by the IRB. As a result, chart review protocols must still be submitted to the IRB for this exempt determination. “Exempt” merely means that the study is minimal risk such that it does not require ongoing oversight by the IRB.

What category of exempt is a chart review?

There are different categories of Exempt status for research studies. Chart reviews generally fall under Exempt Category 4(ii) or 4(iii). These are:

4(ii) Secondary research uses of identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimen – information recorded by investigator in manner that identity of subjects cannot readily be ascertained.

4(iii) Secondary research uses of identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimen – use of identifiable information regulated under HIPAA

Note that the data to be collected for a chart review is considered a “use of identifiable private information”. Because medical records exist for clinical, and not research, purposes, the use of this data for research is considered a “secondary use”.

The choice between Exempt category 4(ii) and 4(iii) depends on whether you will collect identifiers (such as MRN) as part of your study. This will be described in further detail below.

All investigators listed on an IRB application must be up to date with human subjects research training per your institution’s requirements.

At MSU, this training can be found here: https://hrpp.msu.edu/training/index.html

At other institutions, this training requirement may be different.

Online Form

In most cases, the IRB will require the submission of a written protocol document which you attach to an online form. The “IRB Protocol Elements” information below is a combination of the types of information being requested by the IRB either in the written protocol or in the online form.

At MSU, the online form is in the software “Click”. https://hrpp.msu.edu/click/index.html

Note that every member of the research team who is to be added to an IRB Protocol at MSU must log in to Click at least once. If an investigator has not ever logged into Click before, they will not show up in the system and cannot be added to the protocol. If you or someone on your research team is unable to add a person to the online protocol in Click, tell that person to log in to Click at least once.

There are different online systems used by different institutions, such as IRB Manager, SMART IRB, and other online systems.

IRB PROTOCOL ELEMENTS

Background & Significance

IRB protocols should contain a background and significance section where the investigators outline for the IRB the basic background of the study along with its significance. Remember, the IRB committee and the IRB analysts reviewing and processing your requests are not necessarily experts in your field, so you must provide them with adequate background on your study, along with the significance of the study. This will establish the importance of doing the study in the first place. It is within the rights of the IRB to decline approval of a study if they feel the risk of doing the study, no matter how minor, is more than the benefit of having the study results. That’s why it’s important to clearly explain the background and significance.

The objectives of your study are the main outcomes of your study as you define them. They are not broad goals, such as “to cure cancer”, or vague ideas, such as “to see if drug A works”. Instead, they are specific outcomes that you will measure.

For example, if you were doing a Covid-19 vaccine trial, your objectives would be something like, “The primary objective of this study is to determine if patients who received the experimental vaccine were diagnosed with Covid-19 at a lower rate than patients who received placebo as determined by RT-PCR testing.” You can add secondary objectives as well, such as “Secondary objectives include assessing severity of illness in the vaccinated vs. placebo group. Severity is to be measured as presence of symptoms, hospitalization rate, rate of admission to ICU, and death rate.”

Study Design

This section can be very short. An example might be: “Retrospective cohort study”.

That’s it. Note, again, that “retrospective chart review” is not a design, it’s a method. Therefore, “retrospective chart review” may not be enough without more info on the design (i.e. case series, case control, cohort study…).

Recruitment Methods

For a retrospective chart review, there is no recruitment of subjects. Simply state this in the IRB application or write N/A.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The IRB will ask you to describe your research subjects. Inclusion criteria refers to the characteristics of patients that make it so they may be included in your study. Here is an example:

“Patients aged 18 and older who received Roux en Y gastric bypass surgery at Smith Memorial Hospital between the dates of January 1, 2019 and January 1, 2022.”

Note that description includes location and dates, along with the clinical and patient characteristics that qualify the patient for inclusion. There may be quite a few criteria in this list.

Exclusion criteria are characteristics of the patients that would exclude the patient from the study EVEN IF they meet the inclusion criteria.

Example: “Patients who received prior weight loss surgery” or

“Patients who did not have a follow-up visit at 6- and 12- months post-surgery”.

Study Endpoints

For a chart review, the study endpoint is simply the measurement you are using for the primary (and secondary, if necessary) outcomes in your study. For example, let’s say you were doing a retrospective study in a cohort of patients with Parkinson’s disease and you were interested in seeing if their exercise level helped in slowing progression of disease. Assume that you have a log of physical activity for these patients over a period of time. The endpoints in this study would be the measures of clinical progression of Parkinson’s in these patients. There could be multiple endpoints, as Parkinson’s has both motor and cognitive symptoms. As such, endpoints may be stability or balance, tremor, or measures of dementia.

Note that study endpoints may be vastly different for more risky studies, such as RCTs, and may include safety endpoints and effectiveness endpoints.

Study Procedures

The procedures of a chart review include:

- How the patients will be identified

- Who will collect the data and from where (i.e. the EMR)

- Whether identifiers will be collected, and which identifiers

- Where the data will be stored (i.e. spreadsheet, database, REDCap, etc.), this includes where both the data sheet AND identifiers are stored

- How you will protect the data (i.e. password protected, secure storage drive), including both data sheet and identifiers (if applicable)

- Who will have access to the data

- How data will be shared with others (such as statisticians, if applicable)

Some notes on the above items. The procedures of a chart review are mostly grabbing data from the EMR or other source of data and storing this data securely somewhere. This can occur by hand (i.e. student collects data directly from the EMR), through the use of an honest broker, with the help of the Health IT department, and so on.

On Identifiers

Of particular importance is the issue of identifiers. When it comes to chart review studies, the term “identifiers” refers to HIPAA identifiers. Here is a list of them, per the HHS ( https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/special-topics/de-identification/index.html ):

- All geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, including street address, city, county, precinct, ZIP code, and their equivalent geocodes, except for the initial three digits of the ZIP code if, according to the current publicly available data from the Bureau of the Census: (1) The geographic unit formed by combining all ZIP codes with the same three initial digits contains more than 20,000 people; and (2) The initial three digits of a ZIP code for all such geographic units containing 20,000 or fewer people is changed to 000

- All elements of dates (except year) for dates that are directly related to an individual, including birth date, admission date, discharge date, death date, and all ages over 89 and all elements of dates (including year) indicative of such age, except that such ages and elements may be aggregated into a single category of age 90 or older

- Telephone numbers

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers

- Fax numbers

- Device identifiers and serial numbers

- Email addresses

- Web Universal Resource Locators (URLs)

- Social security numbers

- Internet Protocol (IP) addresses

- Medical record numbers

- Biometric identifiers, including finger and voice prints

- Health plan beneficiary numbers

- Full-face photographs and any comparable images

- Account numbers

- Certificate/license numbers

- Any other unique identifying number, characteristic, or code, except as permitted by paragraph (c) of this section [Paragraph (c) is presented below in the section “Re-identification”]

Be aware that if you have a data sheet with protected health information (PHI) and identifiers, and you let someone not authorized view this sheet, you have committed a HIPAA violation. Because of this, a strategy to protect data must be part of your research protocol.

There are two ways to protect confidentiality of patient data in a chart review.

- Do not collect identifiers

- Utilize codes to allow re-identification

If you collect data without identifiers (#1 above), this is called safe harbor de-identification. If there are no identifiers in your data set, and the covered entity (hospital, clinic, practice…) has no reasonable basis to expect that individual patients can be identified from the data, then it is not subject to HIPAA privacy rules. This type of data can be shared with statisticians.

If you do collect identifiers (#2 above), you do not want to include those in the same data sheet as the health information. You would instead utilize a “correlation tool” or “key to identifiers”. In this strategy, you remove identifiers from the data, and place them in a separate file which only has identifiers. You then give each subject a code (i.e. P1, P2, P3…) which you enter into both sheets. On one sheet, you have a patient code linked to identifiers, in the other sheet you have a patient code linked to the patient’s health and demographic data. In this way, you can utilize the code to re-identify the patient.

Here is a link to an example of a basic correlation tool and data collection sheet to illustrate this concept.

Sample Correlation Tool and Data Collection Sheet

If you want to use codes, you need to explain why you should be allowed to do this. Here is some sample language that explains why one might want to re-identify subjects in a chart review:

“The use of a correlation tool is being requested to allow re-identification of subjects. This request is being made for two main reasons. 1) In the case of data transcription errors (e.g. age of 350 years), researchers will be allowed to go back into the EMR to correct the errors. 2) Upon submission of the work for publication, it is often a reviewer request to strengthen the study by the inclusion of additional data in the study. With a correlation tool, investigators can go back into the EMR to collect additional data to improve the study.”

Monitoring Data for the Safety of Participants

This section can be completed by writing “N/A”.

As a chart review, you will not be interacting or intervening with subjects in any way. You are doing a secondary analysis of data collected for medical care, as such your chart review study has no bearing on subject safety.

Withdrawal of Subjects

Simply answer “Retrospective chart review, no possibility of subject withdrawal”.

Statistical Plan

In this section, you will have to describe your statistical plan, which can include a discussion or rationale for your sample size determination. If you need help with this section, please contact a statistician (see here for MSU CSTAT help - https://research.chm.msu.edu/students-residents/statistical-help ).

Risks and Benefits

For a chart review, there are no direct benefits to subjects and the main risk is to data confidentiality. In other parts of the protocol, you will state what the data confidentiality procedures are, so you don’t have to repeat them here.

Provisions to Protect the Privacy of Subjects

There are no privacy risks with a retrospective chart review. Privacy = people. State something like this in your application, “This is a retrospective chart review, there are no privacy risks because there will be no interaction or intervention with subjects.”

Provisions to Protect the Confidentiality of Data

There are data confidentiality risks. In this section, you would describe how you are protecting the data. Some key things to mention include:

- Data will be stored securely (password protected, secure storage drive, use of REDCap, etc.)

- Only investigators listed on the IRB will have access to data files

- Correlation tool (or key to identifiers) will be used and stored separately from data files

- Correlation tool will be destroyed at final publication/presentation of study (if you plan to do this)

Medical Care or Compensation for Injury

Answer “N/A”, the reason being you are not interacting or intervening with subjects.

Cost to Subjects

“N/A” for the same reason as above.

Consent Process

For a chart review, you will be requesting a “waiver of informed consent”. Here is some sample language on why you would be granted a waiver:

“A waiver of informed consent is requested because this is a minimal risk retrospective chart review in which no patient interaction will occur. Obtaining informed consent will require contacting each patient directly, increasing the risks to patient privacy. Further, obtaining a signed consent form will increase the risks to data confidentiality due to creation of an additional document containing a patient identifier. Also, requiring informed consent will result in a certain number of patients who will be lost to follow up, or who might not agree to be in the study, thereby reducing the sample size and reducing the impact of this study. Further, a reduced sample size may require contacting additional potential participants to meet our enrollment goals, and/or expansion of the time frame for inclusion of study subjects, thereby introducing more risk to privacy and confidentiality. Patient rights and welfare will not be affected in any way by this study.”

Vulnerable Populations

Describe any vulnerable subjects that are purposely included in your study. Here is a list of potential vulnerable subjects:

- Pregnant women

- Human fetuses

- Individuals with physical disabilities

- Individuals with mental disabilities or cognitive impairments

Note that this is not a comprehensive list.

In the IRB application, you must describe vulnerable populations if they are purposely included. Thus, if you are doing a study on pregnant women and their exposure to environmental pollutants at work, you would describe this population. However, if your study was on adults 18-65 years old who have asthma, you may have pregnant women as part of your study, but you do not have to describe them as a vulnerable population because you are not purposely including them in your study.

Vulnerable populations are described here because they are vulnerable to coercion or undue influence, and you are being asked to explain any additional safeguards to protect them. In the case of a chart review, if you have vulnerable populations, there are generally no additional safeguards in place. This is because you are not interacting with subjects or intervening in any way. As such, simply state that no additional safeguards are in place beyond the data protection procedures already described.

Sharing Results with Subjects

For a chart review, state that results will not be shared with subjects.

Include a list of references in your protocol.

Attachments

Attach all documents requested by the IRB. This may include a blank version of your data collection sheet or a blank version of your correlation tool (if applicable). Since you are requesting a waiver of informed consent, you will not have to attach an informed consent form. Likewise, you will not have to attach any recruitment materials or messages to participants because you will not be interacting with subjects in any way.

After Submission to the IRB

At MSU, only the PI can submit the IRB application. If you are not the PI of the study, and you are ready to submit your IRB application, please notify your PI to do so.

Once submitted, check the IRB page in Click regularly for comments. If you would like your application to be reviewed and approved quickly, respond to all questions in a timely manner. Responding to an IRB question in Click also requires the PI to submit that comment. If you are not the PI, and you want to respond to an IRB question, let your PI know they have to submit response or comment.

*Content developed by Mark D. Trottier, PhD

Retrospective Studies and Chart Reviews

Chris nickson.

- Nov 3, 2020

- Retrospective studies are designed to analyse pre-existing data, and are subject to numerous biases as a result

- Retrospective studies may be based on chart reviews (data collection from the medical records of patients)

- case series

- retrospective cohort studies (current or historical cohorts)

- case-control studies

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS USED IN RETROSPECTIVE STUDIES

- Compare outcomes between treatment and control group

- Used if treatment and control group are selected by a chance mechanism

- Divide all patients into subgroups according to a risk factor, then perform comparison within these subgroups

- Used if only one key confounding variable exists

- Find pairs of patients that have specific characteristics in common, but received different treatments; compares outcome only in these pairs

- Used if only a few confounders exist and if the size of one of the comparison groups is much larger than the other

- More than one confounder is controlled simultaneously, if a larger number of confounders needs to be adjusted for computer software and statistical advice is necessary

- Used if sample size is large

- Simple description of data

- Used if sample size is low and other options failed

ADVANTAGES OF RETROSPECTIVE STUDIES

- quicker, cheaper and easier than prospective cohort studies

- can address rare diseases and identify potential risk factors (e.g. case-control studies)

- not prone to loss of follow up

- may be used as the initial study generating hypotheses to be studied further by larger, more expensive prospective studies

DISADVANTAGES OF RETROSPECTIVE STUDIES

- inferior level of evidence compared with prospective studies

- controls are often recruited by convenience sampling, and are thus not representative of the general population and prone to selection bias

- prone to recall bias or misclassification bias

- subject to confounding (other risk factors may be present that were not measured)

- cannot determine causation, only association

- some key statistics cannot be measured

- temporal relationships are often difficult to assess

- retrospective cohort studies need large sample sizes if outcomes are rare

SOURCES OF ERROR IN CHART REVIEWS AND THEIR SOLUTIONS

From Kaji et al (2014) and Gilbert et al (1996):

- establish whether necessary information is available in the charts

- establish if there are sufficient charts to perform the analysis with adequate precision

- perform a sample size calculation

- Declare any conflict of interest Provide evidence of institutional review board approval

- Submit the data collection form, as well as the coding rules and definitions, as an online appendix

- Case selection or exclusion using explicit protocols and well described the criteria

- Ensure all available charts have an equal chance of selection

- Provide a flow diagram showing how the study sample was derive from the source population

- define the predictor and outcome variables to be collected a priori

- Develop a coding manual and publish as an online appendix

- Use standardized abstraction forms to guide data collection

- Provide precise definitions of variables

- Pilot test the abstraction form

- Ensure uniform handling of data that is conflicting, ambiguous, missing, or unknown

- Perform a sensitivity analysis if needed

- Blind chart reviewers to the etiologic relation being studied or the hypotheses being tested. If groups of patients are to be compared, the abstractor should be blinded to the patient’s group assignment

- Describe how blinding was maintained in the article

- Train chart abstractors to perform their jobs.

- Describe the qualifications and training of the chart abstracters.

- Ideally, train abstractors before the study starts, using a set of “practice” medical records.

- Ensure uniform training, especially in multi-center studies

- Monitor the performance of the chart abstractors

- Hold periodic meetings with chart abstractors and study coordinators to resolve disputes and review coding rules.

- A second reviewer should re-abstract a sample of charts, blinded to the information obtained by the first correlation reviewer.

- Report a kappa-statistic, intraclass coefficient, or other measure of agreement to assess inter-rater reliability of the data

- Provide justification for the criteria for each variable

SOURCES OF ERROR FROM THE USE OF ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORDS

Potential biases introduced from:

- use of boilerplates (a unit of writing that can be reused over and over without change)

- items copied and pasted

- default tick boxes

- delays in time stamps relative to actual care

References and Links

- CCC — Case-control studies

Journal articles

- Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Barta DC, Steiner J. Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: Where are the methods? Ann Emerg Med. 1996 Mar;27(3):305-8. PMID: 8599488 .

- Kaji AH, Schriger D, Green S. Looking through the retrospectoscope: reducing bias in emergency medicine chart review studies. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Sep;64(3):292-8. PMID: 24746846 .

- Sauerland S, Lefering R, Neugebauer EA. Retrospective clinical studies in surgery: potentials and pitfalls. J Hand Surg Br. 2002 Apr;27(2):117-21. PMID: 12027483 .

- Worster A, Bledsoe RD, Cleve P, Fernandes CM, Upadhye S, Eva K. Reassessing the methods of medical record review studies in emergency medicine research. Ann Emerg Med. 2005 Apr;45(4):448-51. PMID: 15795729 .

Critical Care

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at the Alfred ICU in Melbourne. He is also a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University . He is a co-founder of the Australia and New Zealand Clinician Educator Network (ANZCEN) and is the Lead for the ANZCEN Clinician Educator Incubator programme. He is on the Board of Directors for the Intensive Care Foundation and is a First Part Examiner for the College of Intensive Care Medicine . He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives.

After finishing his medical degree at the University of Auckland, he continued post-graduate training in New Zealand as well as Australia’s Northern Territory, Perth and Melbourne. He has completed fellowship training in both intensive care medicine and emergency medicine, as well as post-graduate training in biochemistry, clinical toxicology, clinical epidemiology, and health professional education.

He is actively involved in in using translational simulation to improve patient care and the design of processes and systems at Alfred Health. He coordinates the Alfred ICU’s education and simulation programmes and runs the unit’s education website, INTENSIVE . He created the ‘Critically Ill Airway’ course and teaches on numerous courses around the world. He is one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) and is co-creator of litfl.com , the RAGE podcast , the Resuscitology course, and the SMACC conference.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Twitter, he is @precordialthump .

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Enabling HIPAA-Compliant Clinical Research at Stanford

Enabling Data Driven Clinical Research

Chart review.

Once you have determined which patients seem pertinent to your research inquiry, the next step is usually to review their charts.

The Cohort Discovery Tool and Chart Review Tool share the same URL, https://starr-tools.med.stanford.edu/starr-tools/ . To switch from the Cohort Discovery Tool to the Chart Review tool, either click the "Go to Chart Review" toolbar button, or select "Patient Chart Review" from the dropdown menu in the center of the Cohort Discovery Tool's toolbar.

If you do not see this option in your drop-down, please follow our step-by-step guide to the process of obtaining all requisite institutional approvals.

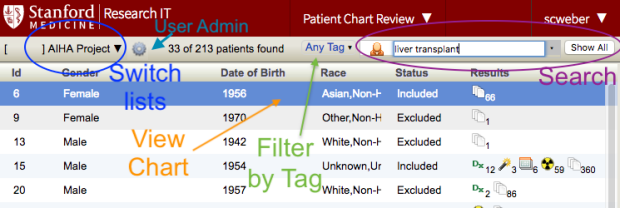

The Chart Review Tool User's Guide is well worth reading as it describes several very handy features of the tool. But very briefly, the first thing you see when switching to Chart Review is your patient list. In this view you can filter the list by typing in the search box in the upper right (see "Search" in the annotated image below), switch to a different list if you have more than one by clicking the name of the saved cohort in the upper left (see "Switch Lists" below), or open the chart of a single patient by double-clicking on a row in the main list ("View Chart").

You can filter the list by the associated tags by clicking on the "Any Tag" dropdown ("Filter by Tag"). You can also search individual chart for keywords; doing so will filter the list of items displayed (see "Search", above). For details on how this powerful feature works and an explanation of the advanced search syntax, please consult the User's Guide .

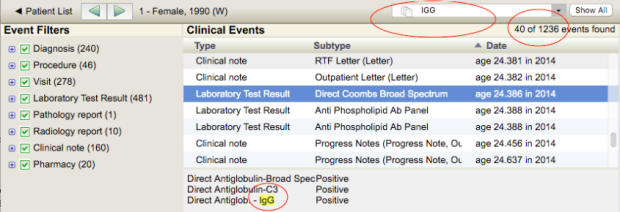

When you double-click on a row (see "View Chart", above), you are taken to that patient's chart. Once in a chart, you can search for keywords in the upper right (circled in red in the image below); the matching terms will be highlighted in yellow in the chart. Click "Show All" to clear your search. You can also show/hide clinical data types by selecting the "Event Filter" checkboxes on the left hand side. To navigate between patients, click the green forward/back arrows in the toolbar. To return to the patient list, click on "< Patient List" in the far left of the toolbar.

Data Download

If you wish to work with the underlying data in .csv file format, you can use the "data download" feature.

If you wish to limit the dataset by date range, enter a start and end date. Both are optional.

As of Spring 2023, the clinical data files available for download consist of patient demographics, encounters, diagnoses, procedures, lab results, flowsheets records, medication orders and administration, clinical notes and documents, radiology reports, pathology reports, SMART data elements, Epic Questionnaires, treatment teams, and immunizations.

In support of HIPAA Minimum Necessary, all clinical data files use the patient "anon id" as the study code to identify the patient. Furthermore all download files are scrubbed of PHI. If your research program requires working with downloaded PHI, you can request an exemption to this policy.

Studies with data privacy permission to see patient identifiers get a patient identifier codebook as part of the data set available for download. The identifier codebook (aka crosswalk) is intended for dataset linkage and quality assurance use only and should not be shared with the researchers doing data analysis.

Note: If you experience difficulty downloading files, try Chrome or Firefox.

The data dictionary is available to everyone at Stanford; if asked to do so, simply log into Google using your [email protected] credentials.

Chart Review Settings Administration

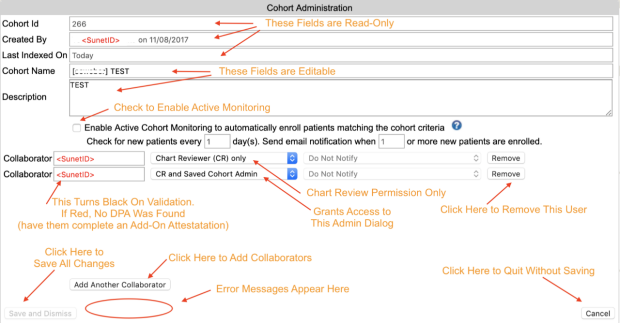

The person who creates a chart review is automatically made into the administrator of the cohort. Administrators can change the cohort name, add and remove users, and enable or disable active cohort monitoring .

To make changes to these settings, click on the gear icon in the upper left. If you see a blue "i" info-button icon rather than a gear, you are not an administrator of the cohort, but clicking on the button will tell you who is an administrator.

"Deleting" a Chart Review

Because cohorts are typically shared between multiple members of a research team, the only way to delete a cohort from your workspace is to remove yourself from it.

To remove yourself from a cohort, go to the patient list screen, click on the settings button in the toolbar (the gear icon), locate yourself on the list of collaborators, and click "Remove".

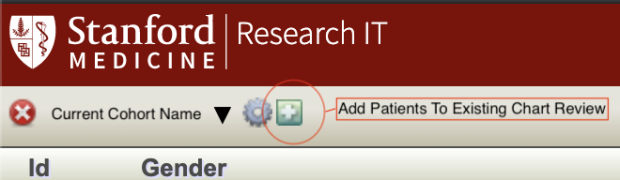

Add Patients to Existing Chart Review

To add patients to your chart review, you must have a list of MRNs. Click the green plus icon the right of the gear icon used to launch the Settings Administration to launch the dialog

Note that the server will double check your MRNs and notify you if any seem to be incorrect. It will also silently discard MRNs that are already included in your cohort, so you don't wind up with duplicate charts. If you find that fewer new records were added than you expect, double check your existing cohort for any overlap with the MRNs you tried to upload.

Establishing a Valid, Reliable, and Efficient Chart Review Process for Research in Pediatric Integrated Primary Care Psychology

- Published: 10 May 2022

- Volume 29 , pages 538–545, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Danielle R. Hatchimonji ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6772-8173 1 , 3 ,

- Jennie David 1 ,

- Carmelita Foster 1 ,

- Franssy Zablah 1 ,

- Alexandra Cross-Knorr 1 , 2 ,

- Erica Sood 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Meghan Lines 1 , 2 &

- Cheyenne Hughes-Reid 1 , 2

532 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Retrospective chart review is an accessible form of research that is commonly used across medical fields but is underutilized in behavioral health. As a relatively newer area of research, the field of pediatric integrated primary care (IPC) would particularly benefit from guidelines for conducting a methodologically sound chart review study. Here, we use our experiences building a chart review procedure for a pediatric IPC research project to offer strategies for optimizing reliability (consistency), validity (accuracy), and efficiency. We aim to provide guidance for conducting a chart review study in the specific setting of pediatric IPC so that researchers can apply this methodology toward generating research in this field.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Real-World Evidence to Assess Medication Safety or Effectiveness in Children: Systematic Review

The role of electronic health records in improving pediatric nursing care: a systematic review

Qualitative Evidence in Pediatrics

Data availability.

Available by request.

Code Availability

Not Applicable.

Berry, K. J., Johston, J. E., & Mielke, P. W. (2008). Weighted Kappa for multiple raters. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 107 , 837–848.

Article Google Scholar

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20 (1), 37–46.

Coleman, N., Halas, G., Peeler, W., Casaclang, N., Williamson, T., & Katz, A. (2015). From patient care to research: A validation study examining the factors contributing to data quality in a primary care electronic medical record database. BMC Family Practice, 16 , 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0223-z

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Flood, M., & Small, R. (2009). Researching labour and birth events using health information records: Methodological challenges. Midwifery, 25 (6), 701–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2007.12.003

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gearing, R. E., Mian, I. A., Barber, J., & Ickowicz, A. (2006). A methodology for conducting retrospective chart review research in child and adolescent psychiatry. Journal of Canadian Academicy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 15 (3), 126–134.

Google Scholar

Gilbert, E. H., Lowenstein, S. R., Koziol-Mclain, J., Barta, D. C., & Steiner, J. (1996). Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: Where are the methods? Annals of Emergency Medicine, 27 , 305–308.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Gregory, K. E., & Radovinsky, L. (2012). Research strategies that result in optimal data collection from the patient medical record. Applied Nursing Research, 25 (2), 108–116.

Hoff, A., Hughes-Reid, C., Sood, E., & Lines, M. (2020). Utilization of integrated and colocated behavioral health models in pediatric primary care. Clinical Pediatrics . https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922820942157

Zozus, M. N., Pieper, C., Johnson, C. M., Johnson, T. R., Franklin, A., Smith, J., & Zhang, J. (2015). Factors affecting accuracy of data abstracted from medical records. PLoS One, 10 (10), e0138649. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138649

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hoffses, K.W., Ramirez, L.Y., Berdan, L., Tunick, R., Honaker, S.M., Meadows, T.J., Shaffer, L., Robins, P.M., Sturm, L., Stancin, T. (2016). Topical review: Building dompetency: Professional skills for pediatric psychologists in integrated primary care settings. Journal of Pediatric Psychology , 41 (10), 1144–1160. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw066

Liddy, C., Wiens, M., & Hogg, W. (2011). Methods to achieve high interrater reliability in data collection from primary care medical records. Annals of Family Medicine, 9 (1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1195

Lines, M. M. (2019). Advancing the evidence for integrated pediatric primary care psychology: A call to action. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7 (2), 179–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000283

Lowenstein, S. R. (2005). Medical record reviews in emergency medicine: The blessing and the curse. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 45 , 452–455.

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The Kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22 (3), 276–282.

Panacek, E. A. (2007). Performing chart review studies. Air Medical Journal, 26 (5), 206–210.

Talmi, A., Muther, E. F., Margolis, K., Buchholz, M., Asherin, R., & Bunik, M. (2016). The scope of behavioral health integration in a pediatric primary care setting. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41 (10), 1120–1132. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw065

Tan, W., Hu, J., Zhang, H., Wu, P., & He, H. (2015). Kappa coefficient: A popular measure of rater agreement. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 27 (1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215010

Vassar, M., & Holzmann, M. (2013). The retrospective chart review: Important methodological considerations. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 10 , 12.

Worster, A., & Haines, T. (2004). Advanced statistics: Understanding medical record review (MRR) studies. Academic Emergency Medicine, 11 (2), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.aem.2003.03.002

Yawn, B. P., & Wollan, P. (2005). Interrater reliability: Completing the methods description in medical records review studies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161 (10), 974–977. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi122

Download references

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Nemours Children’s Health, Delaware Valley, Wilmington, DE, 19803, USA

Danielle R. Hatchimonji, Jennie David, Carmelita Foster, Franssy Zablah, Alexandra Cross-Knorr, Erica Sood, Meghan Lines & Cheyenne Hughes-Reid

Department of Pediatrics, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, 19107, USA

Alexandra Cross-Knorr, Erica Sood, Meghan Lines & Cheyenne Hughes-Reid

Center for Healthcare Delivery Science & Nemours Cardiac Center, Nemours Children’s Hospital, Delaware Valley, 1600 Rockland Rd, Wilmington, DE, 19803, USA

Danielle R. Hatchimonji & Erica Sood

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by DH, JD, CF, and FZ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DH and JD and all authors commented on and edited previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Danielle R. Hatchimonji .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

Danielle R. Hatchimonji, Jennie David, Carmelita Foster, Franssy Zablah, Alexandra Cross-Knorr, Erica Sood, Meghan Lines, and Cheyenne Hughes-Reid declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Approved by Nemours IRB.

Consent to Participate

Consent for publication, human and animal rights.

Study was approved by Nemours IRB.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hatchimonji, D.R., David, J., Foster, C. et al. Establishing a Valid, Reliable, and Efficient Chart Review Process for Research in Pediatric Integrated Primary Care Psychology. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 29 , 538–545 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09881-w

Download citation

Accepted : 13 April 2022

Published : 10 May 2022

Issue Date : September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09881-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Chart review

- Data extraction

- Integrated behavioral health

- Integrated primary care psychology

- Pediatric psychology

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The retrospective chart review (RCR), also known as a medical record review, is a type of research design in which pre-recorded, patient-centered data are used to answer one or more research questions [1].

What is a retrospective chart review? A retrospective chart review is a type of clinical research study in which data is collected solely from the medical record or another patient database. As a result, there is no intervention with research subjects and no interaction with research subjects.

Chart reviews are frequently used for research, care assessments, and quality improvement activities despite an absence of data on reliability and validity. We aim to describe a structured chart review methodology and to establish its validity and reliability.

OVERVIEW. Retrospective studies are designed to analyse pre-existing data, and are subject to numerous biases as a result. Retrospective studies may be based on chart reviews (data collection from the medical records of patients) Types of retrospective studies include: case series. retrospective cohort studies (current or historical cohorts)

Some best practices for creating a RRF include: a) clearly articulating the research question; b) obtaining information about the methods used to gather the data and where the data can be collected (e.g. MRI images, x-ray charts, etc.); c) identifying where the

The Chart Review Tool User's Guide is well worth reading as it describes several very handy features of the tool. But very briefly, the first thing you see when switching to Chart Review is your patient list.

A Prospective Chart Review evaluates patient data that does not yet exist at the time the project is submitted to the IRB for initial review. Who may conduct chart reviews? Only individuals with existing legal access to the charts may conduct reviews.

The advantages of conducting chart reviews include: a relatively inexpensive ability to research the rich readily accessible existing data; easier access to conditions where there is a long latency between exposure and disease, allowing the study of rare occur-rences; and most importantly, the generation of hypotheses that then would be tested p...

Chart review is an accessible form of research that is underutilized in behavioral health. We aimed to provide explicit guidance for conducting a chart review study in the specific setting of pediatric IPC so that researchers can apply this methodology toward generating research in the IPC field.

In this paper, we review and discuss ten common methodological mistakes found in retrospective chart reviews. The ret-rospective chart review is a widely applicable research methodology that can be used by healthcare disciplines as a means to direct subsequent prospective investigations.