- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Thomas Jefferson

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 22, 2022 | Original: October 29, 2009

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), author of the Declaration of Independence and the third U.S. president, was a leading figure in America’s early development. During the American Revolutionary War (1775-83), Jefferson served in the Virginia legislature and the Continental Congress and was governor of Virginia. He later served as U.S. minister to France and U.S. secretary of state and was vice president under John Adams (1735-1826).

Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican who thought the national government should have a limited role in citizens’ lives, was elected president in 1800. During his two terms in office (1801-1809), the U.S. purchased the Louisiana Territory and Lewis and Clark explored the vast new acquisition. Although Jefferson promoted individual liberty, he also enslaved over six hundred people throughout his life. After leaving office, he retired to his Virginia plantation, Monticello, and helped found the University of Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson’s Early Years

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, a plantation on a large tract of land near present-day Charlottesville, Virginia . His father, Peter Jefferson (1707/08-57), was a successful planter and surveyor and his mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson (1720-76), came from a prominent Virginia family. Thomas was their third child and eldest son; he had six sisters and one surviving brother.

Did you know? In 1815, Jefferson sold his 6,700-volume personal library to Congress for $23,950 to replace books lost when the British burned the U.S. Capitol, which housed the Library of Congress, during the War of 1812. Jefferson's books formed the foundation of the rebuilt Library of Congress's collections.

In 1762, Jefferson graduated from the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, where he reportedly enjoyed studying for 15 hours, then practicing violin for several more hours on a daily basis. He went on to study law under the tutelage of respected Virginia attorney George Wythe (there were no official law schools in America at the time, and Wythe’s other pupils included future Chief Justice John Marshall and statesman Henry Clay ).

Jefferson began working as a lawyer in 1767. As a member of colonial Virginia’s House of Burgesses from 1769 to 1775, Jefferson, who was known for his reserved manner, gained recognition for penning a pamphlet, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” (1774), which declared that the British Parliament had no right to exercise authority over the American colonies .

Why Thomas Jefferson’s Anti‑Slavery Passage Was Removed from the Declaration of Independence

The Founding Fathers were fighting for freedom—just not for everyone.

Thomas Jefferson: America’s Pioneering Gourmand

Founding Father, author of the Declaration of Independence, third president of the United States, appropriator of the Louisiana Purchase, gastronome…?

Jefferson & Adams: Founding Frenemies

The two founding fathers, who share a special place in American history, had a long, complicated relationship over the course of their lives.

Marriage and Monticello

After his father died when Jefferson was a teen, the future president inherited the Shadwell property. In 1768, Jefferson began clearing a mountaintop on the land in preparation for the elegant brick mansion he would construct there called Monticello (“little mountain” in Italian). Jefferson, who had a keen interest in architecture and gardening, designed the home and its elaborate gardens himself.

Over the course of his life, he remodeled and expanded Monticello and filled it with art, fine furnishings and interesting gadgets and architectural details. He kept records of everything that happened at the 5,000-acre plantation, including daily weather reports, a gardening journal and notes about his slaves and animals.

On January 1, 1772, Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton (1748-82), a young widow. The couple moved to Monticello and eventually had six children; only two of their daughters—Martha (1772-1836) and Mary (1778-1804)—survived into adulthood. In 1782, Jefferson’s wife Martha died at age 33 following complications from childbirth. Jefferson was distraught and never remarried. However, it is believed he fathered more children with one of his enslaved women, Sally Hemings (1773-1835), who was also his wife’s half-sister .

Slavery was a contradictory issue in Jefferson’s life. Although he was an advocate for individual liberty and at one point promoted a plan for the gradual emancipation of slaves in America, he enslaved people throughout his life. Additionally, while he wrote in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” he believed African Americans were biologically inferior to whites and thought the two races could not coexist peacefully in freedom. Jefferson inherited some 175 enslaved people from his father and father-in-law and owned an estimated 600 slaves over the course of his life. He freed only a small number of them in his will; the majority were sold following his death.

Thomas Jefferson and the American Revolution

In 1775, with the American Revolutionary War recently underway, Jefferson was selected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Although not known as a great public speaker, he was a gifted writer and at age 33, was asked to draft the Declaration of Independence (before he began writing, Jefferson discussed the document’s contents with a five-member drafting committee that included John Adams and Benjamin Franklin ). The Declaration of Independence , which explained why the 13 colonies wanted to be free of British rule and also detailed the importance of individual rights and freedoms, was adopted on July 4, 1776.

In the fall of 1776, Jefferson resigned from the Continental Congress and was re-elected to the Virginia House of Delegates (formerly the House of Burgesses). He considered the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which he authored in the late 1770s and which Virginia lawmakers eventually passed in 1786, to be one of the significant achievements of his career. It was a forerunner to the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution , which protects people’s right to worship as they choose.

From 1779 to 1781, Jefferson served as governor of Virginia, and from 1783 to 1784, did a second stint in Congress (then officially known, since 1781, as the Congress of the Confederation). In 1785, he succeeded Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) as U.S. minister to France. Jefferson’s duties in Europe meant he could not attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787; however, he was kept informed of the proceedings to draft a new national constitution and later advocated for including a bill of rights and presidential term limits.

Jefferson's Path to the Presidency

After returning to America in the fall of 1789, Jefferson accepted an appointment from President George Washington (1732-99) to become the new nation’s first secretary of state. In this post, Jefferson clashed with U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755/57-1804) over foreign policy and their differing interpretations of the U.S. Constitution. In the early 1790s, Jefferson, who favored strong state and local government, co-founded the Democratic-Republican Party to oppose Hamilton’s Federalist Party , which advocated for a strong national government with broad powers over the economy.

In the presidential election of 1796, Jefferson ran against John Adams and received the second-highest amount of votes, which, according to the law at the time, made him vice president.

Jefferson ran against Adams again in the presidential election of 1800, which turned into a bitter battle between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Jefferson defeated Adams; however, due to a flaw in the electoral system, Jefferson tied with fellow Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr (1756-1836). The House of Representatives broke the tie and voted Jefferson into office. In order to avoid a repeat of this situation, Congress proposed the Twelfth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which required separate voting for president and vice president. The amendment was ratified in 1804.

Jefferson Becomes Third U.S. President

Jefferson was sworn into office on March 4, 1801; he was the first presidential inauguration held in Washington, D.C. ( George Washington was inaugurated in New York in 1789; in 1793, he was sworn into office in Philadelphia, as was his successor, John Adams, in 1797.) Instead of riding in a horse-drawn carriage, Jefferson broke with tradition and walked to and from the ceremony.

One of the most significant achievements of Jefferson’s first administration was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million in 1803. At more than 820,000 square miles, the Louisiana Purchase (which included lands extending between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico to present-day Canada) effectively doubled the size of the United States. Jefferson then commissioned explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the uncharted land, plus the area beyond, out to the Pacific Ocean. (At the time, most Americans lived within 50 miles of the Atlantic Ocean.) Lewis and Clark’s expedition , known today as the Corps of Discovery, lasted from 1804 to 1806 and provided valuable information about the geography, American Indian tribes and animal and plant life of the western part of the continent.

Louisiana Purchase: The Land Deal of the Millennium

For a mere $15 million, Thomas Jefferson doubled the size of the United States, buying 800,000 square miles from the French that stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains.

Lewis and Clark: A Timeline of the Extraordinary Expedition

In 1804, Lewis and Clark set off on a journey filled with harrowing confrontations, harsh weather and fateful decisions as they scouted a route across the American West.

How Sally Hemings and Other Enslaved People Secured Precious Pockets of Freedom

In navigating lives of privation and brutality, enslaved people haggled, often daily, for liberties small and large.

In 1804, Jefferson ran for re-election and defeated Federalist candidate Charles Pinckney (1746-1825) of South Carolina with more than 70 percent of the popular vote and an electoral count of 162-14. During his second term, Jefferson focused on trying to keep America out of Europe’s Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). However, after Great Britain and France, who were at war, both began harassing American merchant ships, Jefferson implemented the Embargo Act of 1807.

The act, which closed U.S. ports to foreign trade, proved unpopular with Americans and hurt the U.S. economy. It was repealed in 1809 and, despite the president’s attempts to maintain neutrality, the U.S. ended up going to war against Britain in the War of 1812. Jefferson chose not to run for a third term in 1808 and was succeeded in office by James Madison (1751-1836), a fellow Virginian and former U.S. secretary of state.

Thomas Jefferson’s Later Years and Death

Jefferson spent his post-presidential years at Monticello, where he continued to pursue his many interests, including architecture, music, reading and gardening. He also helped found the University of Virginia, which held its first classes in 1825. Jefferson was involved with designing the school’s buildings and curriculum and ensured that unlike other American colleges at the time, the school had no religious affiliation or religious requirements for its students.

Jefferson died at age 83 at Monticello on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Coincidentally, John Adams, Jefferson’s friend, former rival and fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence, died the same day . Jefferson was buried at Monticello. However, due to the significant debt the former president had accumulated during his life, his mansion, furnishing and enslaved people were sold at auction following his death. Monticello was eventually acquired by a nonprofit organization, which opened it to the public in 1954.

Jefferson remains an American icon. His face appears on the U.S. nickel and is carved into stone at Mount Rushmore . The Jefferson Memorial, near the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated on April 13, 1943, the 200th anniversary of Jefferson’s birth.

HISTORY Vault: U.S. Presidents

Stream U.S. Presidents documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

You make our work possible. Please help us continue.

- Thomas Jefferson

Brief Biography of Thomas Jefferson

Who was thomas jefferson, lawyer. father. scientist. writer. revolutionary. governor. diplomat. vice-president. president. philosopher. architect. slave owner..

Many words describe Thomas Jefferson. He is best remembered for writing the Declaration of Independence, for serving as the third president of the United States, and for championing universal rights while holding over 600 people in slavery. But he also promoted religious freedom , doubled the size of the country , founded a public university , helped establish the nation's capital city , established America's first opposition party , participated in its first peaceful transfer of political power , and made many other contributions to American society.

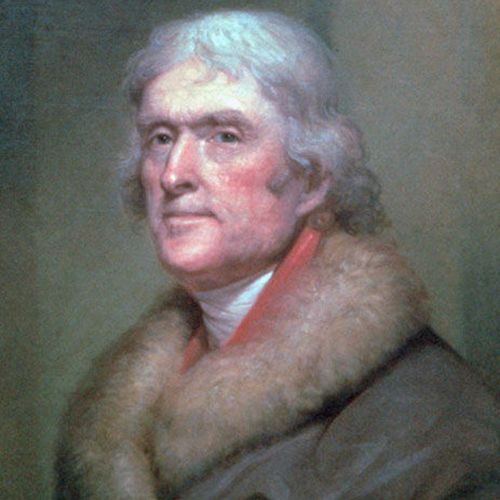

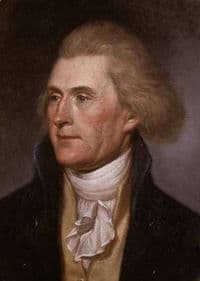

Born April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, Virginia; died July 4, 1826, Monticello - Portrait of Jefferson by Gilbert Stuart (links to all images at bottom of page)

Jefferson's Early Life and Education

Jefferson was born April 13, 1743, on his father’s plantation of Shadwell located along the Rivanna River near the Blue Ridge Mountains of colonial Virginia. 1 His father Peter Jefferson was a successful planter and surveyor, and his mother, Jane Randolph, was a member of one of Virginia’s most distinguished families. When Jefferson was fourteen, his father died, and he inherited a sizeable estate of approximately 5,000 acres. That inheritance included the house at Shadwell, but Jefferson dreamed of living on a mountain. 2

Shadwell, where it all began

As young boy Jefferson studied mathematics, history, Latin, Greek, and French. In 1760, he entered College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. In 1762, he began to study law with prominent Virginia jurist, George Wythe, and recorded his first legal case in 1767. Two years later, he was elected to Virginia’s House of Burgesses (the legislature in colonial Virginia).

- Related: Article on Jefferson's Formal Education

In 1768 he directed the clearing of the top of the 868-foot mountain above Shadwell where he played as a boy. 3 He would name this mountain—and the house he designed there—Monticello. He later referred to this ongoing project, the home that he loved, as “my essay in Architecture.” 4 The following year, he began construction of the small two-story brick structure where he and his wife, Martha Wayles Jefferson, lived with their first child Martha during the first years of their marriage.

The small building where Jefferson and his family lived 1772 to 1775 during early construction of the main house. Image by Rendersphere, LLC

Monticello I, as it looked in the 1780s. Image by RenderSphere, LLC.

Unfortunately, Martha would never see the completion of the grander house Jefferson envisioned; she died in the tenth year of their marriage, and Jefferson lost “the cherished companion of my life.” Their marriage produced six children, but only two survived into adulthood, Martha (known as Patsy) and Mary (known as Maria or Polly). 5

Martha Wayles Jefferson, a Vivid Personality

In this short video, hear how Martha Wayles Jefferson stands out as a vivid personality in the recollections of those who knew and remembered her.

Along with the land, Jefferson inherited slaves from his father and even more slaves from his father-in-law, John Wayles ; he also bought and sold enslaved people. In a typical year, he owned about 200, almost half of them under the age of sixteen. About eighty of these enslaved individuals lived at Monticello; the others lived on his adjacent Albemarle County farms, and on his Poplar Forest estate in Bedford County, Virginia. Over the course of his life, he owned over 600 enslaved people. These men, women and children were integral to the running of his farms and building and maintaining his home at Monticello. Some were given training in various trades, others worked the fields, and some worked inside the main house.

Many of the enslaved house servants were members of the Hemings family. Elizabeth Hemings and her children were a part of the Wayles estate and tradition says that John Wayles was the father of six of Hemings’s children and, thus, they were the half-brothers and sisters of Jefferson’s wife Martha. Jefferson gave the Hemingses special positions, and the only slaves Jefferson freed in his lifetime and in his will were all Hemingses, giving credence to the oral history. Years after his wife’s death, Jefferson fathered at least six of Sally Hemings’s children. Four survived to adulthood and are mentioned in Jefferson’s plantation records. Their daughter Harriet and eldest son Beverly were allowed to leave Monticello during Jefferson’s lifetime and the two youngest sons, Madison and Eston , were freed in Jefferson’s will.

- More on Jefferson and Slavery »

Professional and Political Life

Jefferson's first political work to gain broad acclaim was a 1774 draft of directions for Virginia’s delegation to the First Continental Congress, reprinted as a “Summary View of the Rights of British America.” Here he boldly reminded George III that, “he is no more than the chief officer of the people, appointed by the laws, and circumscribed with definite powers, to assist in working the great machine of government. . . .” Nevertheless, in his “Summary View” he maintained that it was not the wish of Virginia to separate from the mother country. 6

Primary Author of the Declaration of Independence

Yet two years later as a member of the Second Continental Congress and chosen to draft the Declaration of Independence , Jefferson put forward the Colonies’ arguments for declaring themselves free and independent states. The Declaration has been regarded as a charter of American and universal liberties. The document proclaims that all men are equal in rights, regardless of birth, wealth, or status; that those rights are inherent in each human, a gift of the creator, not a gift of government, and that government is the servant and not the master of the people.

1788 portrait by John Trumbull depicting Jefferson as the 33-year-old author of the Declaration

Jefferson recognized that the principles he included in the Declaration had not been fully realized and would remain a challenge across time, but his poetic vision continues to have a profound influence in the United States and around the world. Abraham Lincoln made just this point when he declared:

All honor to Jefferson – to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence by a single people, had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, and so to embalm it there, that to-day and in all coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of reappearing tyranny and oppression. 7

After Jefferson left Congress in 1776, he returned to Virginia and served in the legislature. In late 1776, as a member of the new House of Delegates of Virginia, he worked closely with James Madison. Their first collaboration, to end the religious establishment in Virginia, became a legislative battle which would culminate with the passage of Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom in 1786.

Governor of Virginia

Elected governor from 1779 to 1781, he suffered an inquiry into his conduct during the British invasion of Virginia in his last year in office that, although the investigation was finally repudiated by the General Assembly, left him with a life-long pricklishness in the face of criticism and generated a life-long enmity toward Patrick Henry whom Jefferson blamed for the investigation. The investigation “inflicted a wound on my spirit which will only be cured by the all-healing grave” Jefferson told James Monroe. 8

During the brief private interval in his life following his governorship, Jefferson completed the one book which he authored, Notes on the State of Virginia . Several aspects of this work were highly controversial. With respect to slavery, in Notes Jefferson recognized the gross injustice of the institution – warning that because of slavery “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his Justice cannot sleep for ever.” But he also expressed racist views of blacks’ abilities; albeit he recognized that his views of their limitations might result from the degrading conditions to which they had been subjected for many years. With respect to religion, Jefferson’s Notes emphatically supported a broad religious freedom and opposed any establishment or linkage between church and state, famously insisting that “it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.” 9

Minister to France and Secretary of State

In 1784, Jefferson entered public service again, in France, first as a trade commissioner and then as the successor to Benjamin Franklin as minister to France. During this period, he avidly studied European culture, sending home to Monticello, books, seeds and plants, architectural drawings, artwork, furniture, scientific instruments, and information.

In 1790 he agreed to be the first secretary of state under the new Constitution in the administration of the first president, George Washington . His tenure was marked by his opposition to the policies of Alexander Hamilton , which Jefferson believed both encouraged a larger and more powerful national government and were too pro-British.

Portrait of Jefferson by Mather Brown, painted during his time as Minister to France.

President of the United States (1801-1809)

In 1796, as the presidential candidate of the nascent Democratic-Republican Party, he became vice-president after losing to John Adams by three electoral votes. Four years later, he defeated Adams in another hotly contested election and became the U.S.'s third president in 1801, marking the first peaceful transfer of authority from one party to another in the history of the young nation.

Perhaps the most notable achievements of President Jefferson's first term were the purchase of the Louisiana Territory in 1803 and his support of the Lewis and Clark expedition . His second term, a time when he encountered more difficulties on both the domestic and foreign fronts, is most remembered for his efforts to maintain neutrality in the midst of the conflict between Britain and France. Unfortunately, his efforts did not avert a war with Britain in 1812 after he had left office and his friend and colleague, James Madison, had assumed the presidency in 1809.

Jefferson as President

More on Jefferson's two terms as America's third president.

During the last seventeen years of his life, Jefferson generally remained at Monticello, welcoming the many visitors who came to call upon the Sage. During this period, he sold his collection of books (almost 6500 volumes) to the government to form the nucleus of the Library of Congress before promptly beginning to purchase more volumes for his final library. Noting the irony, Jefferson famously told John Adams that “I cannot live without books.” 10

- Monticello today, much as it looked during Jefferson's retirement

Jefferson embarked on his last great public service at the age of seventy-six with the founding of the University of Virginia . He spearheaded the legislative campaign for its charter, secured its location, designed its buildings, planned its curriculum, and served as the first rector.

Unfortunately, Jefferson’s retirement was clouded by debt. Like so many Virginia planters, he had contended with debts most of his adult life, but along with the constant fluctuations in the agricultural markets, he was never able to totally liquidate the sizeable debt attached to the inheritance from his father-in-law John Wayles. His finances worsened in retirement with the War of 1812 and the subsequent recession, headed by the Panic of 1819. He had felt compelled to sign on notes for a friend in 1818, who died insolvent two years later, leaving Jefferson with two $10,000 notes. This he labeled his coup de grâce, as his extensive land holdings in Virginia, with the deflated land prices, could no longer cover what he owed. He complained to James Madison that the economic crisis had “peopled the Western States” and “drew off bidders” for lands in Virginia and along the Atlantic seaboard. 11 Ironically, Jefferson’s greatest accomplishment during his presidency, the purchase of the port of New Orleans and the Louisiana Territory that opened the western migration, would contribute to his financial discomfort in his final years. 12

Despite his debts, when he died just a few hours before his friend John Adams on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1826, he was optimistic as to the future of the republican experiment. Just ten days before his death, he had declined an invitation to the planned celebration in Washington but offered his assurance, “All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man.” 13

Jefferson wrote his own epitaph and designed the obelisk grave marker that was to bear three of his accomplishments and “not a word more:”

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA BORN APRIL 2, 1743 O.S. DIED JULY 4. 1826

He could have filled several markers had he chosen to list his other public offices: third president of the new United States, vice president, secretary of state, diplomatic minister, and congressman. For his home state of Virginia he served as governor and member of the House of Delegates and the House of Burgesses as well as filling various local offices — all tallied into almost five decades of public service. He also omitted his work as a lawyer, architect, writer, farmer, gentleman scientist, and life as patriarch of an extended family at Monticello, both white and black. He offered no particular explanation as to why only these three accomplishments should be recorded, but they were unique to Jefferson.

Jefferson's Three Greatest Achievements

A Monticello guide looks at the three contributions that Jefferson considered his greatest achievements.

Other men would serve as U.S. president and hold the public offices he had filled, but only he was the primary draftsman of the Declaration of Independence and of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom , nor could others claim the position as the Father of the University of Virginia . More importantly, through these three accomplishments he had made an enormous contribution to the aspirations of a new America and to the dawning hopes of repressed people around the world. He had dedicated his life to meeting the challenges of his age: political freedom, religious freedom, and educational opportunity. While he knew that we would continue to face these challenges through time, he believed that America’s democratic values would become a beacon for the rest of the world. He never wavered from his belief in the American experiment.

I have no fear that the result of our experiment will be that men may be trusted to govern themselves. . . . Thomas Jefferson, 2 July 1787

He spent much of his life laying the groundwork to insure that the great experiment would continue.

Links to images on this page

- The "Edgehill" Portrait of Jefferson by Gilbert Stuart, courtesy Thomas Jefferson Foundation and the National Portrait Gallery)

- The South Pavilion as it looked in the early 1780s

- The Monticello house as it looked in the 1780s.

- Portrait of Jefferson by John Trumbull, 1788

- Portrait of Jefferson by Mather Brown, 1786

Videos and podcasts about Jefferson

Learn more about Jefferson's life, career, and legacy in this gallery of recorded livestreams, podcasts, and videos.

Jefferson, Politics, and Citizenship

Timeline of jefferson's public service.

From pro bono law work to founding the University of Virginia, Jefferson's career was one of public service.

The Art of Citizenship

A hub of stories, quotes, videos, biographies, podcasts, and timelines on Jefferson and civics in America.

Articles in our Jefferson Encyclopedia

Jefferson, the person.

Jefferson's personal life, interests, and habits

Jefferson's Community

The people in Jefferson's life.

Articles about Jefferson's political career and accomplishments.

Science and Exploration

Learn more about Jefferson's "tranquil pursuits of science" which he called his "supreme delight."

Information about Jefferson's religious beliefs and his promotion of religious freedom.

Reports some of Jefferson's documents, his correspondence, and his writing habits.

Jefferson in Legend

Anecdotes and stories, generally inaccurate, about Jefferson's life.

1. Jefferson was born April 2nd according to the Julian calendar then in use (“ old style ”), but when the Georgian calendar was adopted in 1752, his birthday became April 13th (“new style”).

2. Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time , 6 vols. (Boston: 1948-77). I:3-33; Appendix I, I:435-46.

3. Jefferson’s Memorandum Books , James A. Bear and Lucia Stanton, eds. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997). I: 76. Transcriptions available at Founders Online

4. Jefferson to Benjamin Latrobe, 10 Oct. 1809, PTJR:RS, 1:595. Transcription available at Founders Online.

5. “Autobiography” in Jefferson’s Writings, PTJ 6:210. Images of printed edition available on the Library of Congress website.

6. PTJ 1:121.

7. Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Henry L. Pierce, et al ., April 6, 1859, John G. Nicolay and John Hay, eds., Abraham Lincoln: Complete Works (New York: Century Co., 1894): 533.

8. Jefferson to James Monroe, May 20, 1782, PTJ 6:185 (ftnt omitted). Transcription available at Founders Online.

9. Notes on the State of Virginia . Ed. by William Peden. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

10. Jefferson to John Adams, 10 June 1815, PTJR 8:522. Transcription available at Founders Online.

11. For coup de grâce and following quote, see Jefferson to James Madison, 17 February 1826, Jefferson Writing, Merrill Peterson, ed. (Library of America, 1984), 1512-15. Transcription available at Founders Online.

12. For Jefferson’s retirement debt see, Herbert Sloan, Principle & Interest: Thomas Jefferson and the Problem of Debt (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995), 202-237; for notes signed in 1818, see p. 219.

13. TJ to Roger Weightman, 24 June 1826. Transcription available at Founders Online.

ADDRESS: 931 Thomas Jefferson Parkway Charlottesville, VA 22902 GENERAL INFORMATION: (434) 984-9800

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was a Founding Father of the United States, author of the Declaration of Independence, and America’s third president.

- Who Was Thomas Jefferson?

Thomas Jefferson was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The native Virginian was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence and later held several national offices. Jefferson served as the nation’s first secretary of state, and the second vice president (under John Adams ), and the third American president, from 1801 to 1809. During his two-term presidency, Jefferson doubled the size of the United States by successfully brokering the Louisiana Purchase and defeated pirates from North Africa during the Barbary War. In retirement, Jefferson founded the University of Virginia and continued work on his beloved Monticello estate. He died on the 50 th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence at age 83.

Quick Facts

When and where was thomas jefferson born, children, wife, and sally hemings, declaration of independence, virginia governor and house delegate, national appointments: minister to france and secretary of state, vice presidency, accomplishments as u.s. president, ideology: political party, views on slavery, and legacy, later years: founding the university of virginia, when did thomas jefferson die.

FULL NAME: Thomas Jefferson BORN: April 13, 1743 DIED: July 4, 1826 BIRTHPLACE: Shadwell, Virginia SPOUSE: Martha Jefferson (1772-1782) CHILDREN: 12 ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Aries

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, at the Shadwell plantation located just outside of Charlottesville, Virginia.

Thomas was born into one of the most prominent families of Virginia’s planter elite. His mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson, was a member of the proud Randolph clan, a family claiming descent from English and Scottish royalty. His father, Peter Jefferson, was a successful farmer as well as a skilled surveyor and cartographer who produced the first accurate map of the Province of Virginia.

Thomas was the third born of 10 siblings. As a boy, his favorite pastimes were playing in the woods, practicing the violin, and reading.

Jefferson began his formal education at age 9, studying Latin and Greek at a local private school run by Reverend William Douglas. In 1757, at the age of 14, he took up further study of the classical languages as well as literature and mathematics with Reverend James Maury, whom Jefferson later described as “a correct classical scholar.”

In 1760, having learned all he could from Maury, Jefferson left home to attend the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia’s capital. Although it was the second oldest college in America (after Harvard), William and Mary wasn’t an especially rigorous academic institution at that time. Jefferson was dismayed to discover that his classmates expended their energies betting on horse races, playing cards, and courting women rather than studying.

Nevertheless, the serious and precocious Jefferson fell in with a circle of older scholars that included Professor William Small, Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier, and lawyer George Wythe, and it was from them that he received his true education.

After three years at William and Mary, Jefferson decided to read law under Wythe, one of the preeminent lawyers of the American colonies. There were no law schools at this time; instead aspiring attorneys “read law” under the supervision of an established lawyer before being examined by the bar.

Wythe guided Jefferson through an extraordinarily rigorous five-year course of study—more than double the typical duration. By the time Jefferson won admission to the Virginia bar in 1767, he was already one of the most learned lawyers in America.

In 1769, Jefferson began construction of what was perhaps his greatest labor of love: Monticello , his house atop a small rise outside of Charlottesville, Virginia. The house was built on land within the state’s Piedmont region that his father had owned since 1735.

In keeping with his interests as one of America’s greatest Renaissance Men—he liked botany, archaeology, music, and birdwatching, among other subjects—Jefferson, himself, drafted the blueprints for Monticello’s neoclassical mansion, outbuildings, and gardens.

More than just a residence, Monticello was also a working plantation, where Jefferson kept roughly 130 Black people in slavery. Their duties included tending gardens and livestock, plowing fields, and working at the onsite textile factory.

Now a museum centered on its original owner, Monticello is open to the public for tours. The property was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1966 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

From 1767 to 1774, Jefferson practiced law in Virginia with great success, trying many cases and winning most of them. During these years, he also met and fell in love with Martha Wayles Skelton, a recent widow and one of the wealthiest women in Virginia.

The pair married on January 1, 1772. Thomas and Martha Jefferson had six children together, but only two survived into adulthood: Martha, their firstborn, and Mary, their fourth, who went by the name “Maria.” Only Martha survived her father.

His six children with Martha, however, weren’t the only kids Jefferson fathered. History scholars and a significant body of DNA evidence indicate that Jefferson had an affair—and several children—with Sally Hemings, one of his enslaved people and the elder Martha’s half-sister. (Sally’s mother, Betty Hemings, was enslaved by Mather’s father, John Wayles, who also fathered Sally.)

It’s overwhelmingly likely, if not absolutely certain, that Jefferson fathered all six of Sally Hemings’ children. Even the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which owns and operates Monticello, has publicly acknowledged this and considers Jefferson’s paternity of Hemings’ children “settled historical matter.” The most compelling proof is DNA evidence, revealed in 1998, showing that some male member of the Jefferson family fathered Hemings’ children, and that it wasn’t Samuel or Peter Carr, the only two of Jefferson’s male relatives in the vicinity at the relevant times.

Only four of Jefferson and Hemings’ six children survived. William Beverly Hemings, Harriet Hemings, James Madison Hemings, and Thomas Eston Hemings were born into slavery, though Jefferson freed them. Still shrouded in history is the exact nature of Jefferson’s relationship with Sally, who was thirty years younger than the Founding Father.

The beginning of Jefferson’s professional life coincided with major changes in Great Britain’s 13 American colonies . The conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763 left Great Britain in dire financial straits; to raise revenue, the Crown levied a host of new taxes on its colonies in America. In particular, the Stamp Act of 1765, which imposed a tax on printed and paper goods, outraged the colonists, giving rise to the American revolutionary slogan, “No taxation without representation.”

Eight years later, on December 16, 1773, colonists protesting a British tea tax dumped 342 chests of tea into the Boston Harbor in what is known as the Boston Tea Party . In April 1775, American militiamen clashed with British soldiers at the Battles of Lexington and Concord , the first conflicts in what developed into the Revolutionary War .

Jefferson was one of the earliest and most fervent supporters of the cause of American independence from Great Britain. He was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1768 and joined its radical bloc, led by Patrick Henry and George Washington .

In 1774, Jefferson penned his first major political work, A Summary View of the Rights of British America , which established his reputation as one of the most eloquent advocates of the American cause. A year later, Jefferson traveled to Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress , which created the Continental Army and appointed Washington as its commander-in-chief. However, the Congress’ most significant work fell to Jefferson himself.

In June 1776, the Congress appointed a five-man committee—Jefferson, John Adams , Benjamin Franklin , Roger Sherman , and Robert Livingston—to draft a Declaration of Independence . The committee then chose Jefferson to author the declaration’s first draft, selecting him for what Adams called his “happy talent for composition and singular felicity of expression.”

Over 17 days, Jefferson drafted one of the most beautiful and powerful testaments to liberty and equality in world history. The document opens with a preamble stating the natural rights of all human beings then continues on to enumerate specific grievances against King George III that absolved the American colonies of any allegiance to the British Crown.

Although the version of the Declaration of Independence adopted on July 4, 1776, had undergone a series of revisions from Jefferson’s original draft, its immortal words remain essentially his own:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights; that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

After authoring the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson returned to Virginia, where, from 1776 to 1779, he served as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. There he sought to revise Virginia’s laws to fit the American ideals he had outlined in the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson successfully abolished the doctrine of entail, which dictated that only a property owner’s heirs could inherit his land, and the doctrine of primogeniture, which required that in the absence of a will a property owner’s oldest son inherited his entire estate.

On June 1, 1779, the Virginia legislature elected Jefferson as the state’s second governor. His two years as governor proved the low point of Jefferson’s political career. Torn between the Continental Army’s desperate pleas for more men and supplies and Virginians’ strong desire to keep such resources for their own defense, Jefferson waffled and pleased no one.

As the Revolutionary War progressed into the South, Jefferson moved the capital from Williamsburg to Richmond, only to be forced to evacuate that city when it, rather than Williamsburg, turned out to be the target of British attack.

On June 1, 1781, the day before the end of his second term as governor, Jefferson was forced to flee his home at Monticello, only narrowly escaping capture by the British cavalry. Although he had no choice but to leave, his political enemies later pointed to this inglorious incident as evidence of cowardice.

Jefferson declined to seek a third term as governor and stepped down on June 4, 1781. Claiming that he was giving up public life for good, he returned to Monticello, where he intended to live out the rest of his days as a gentleman farmer surrounded by the domestic pleasures of his family, his farm, and his books. But the next year, Jefferson was spurred back into public life by private tragedy: the untimely death of his beloved wife, Martha, on September 6, 1782, about six weeks before her 34 th birthday.

After months of mourning, in June 1783, Jefferson returned to Philadelphia to lead the Virginia delegation to the Confederation Congress. In 1785, that body appointed Jefferson to replace Benjamin Franklin as the U.S. minister to France. His official duties as minister consisted primarily of negotiating loans and trade agreements with private citizens and government officials in Paris and Amsterdam.

Although Jefferson appreciated much about European culture—its arts, architecture, literature, food, and wines—he found the juxtaposition of the aristocracy’s grandeur and the masses’ poverty repellant. “I find the general fate of humanity here, most deplorable,” he wrote in one letter.

In Europe, Jefferson rekindled his friendship with John Adams , who served as minister to Great Britain, and his wife, Abigail Adams . The educated and erudite Abigail, with whom Jefferson maintained a lengthy correspondence on a wide variety of subjects, was perhaps the only woman he ever treated as an intellectual equal.

After nearly five years in Paris, Jefferson returned to America at the end of 1789 with a much greater appreciation for his home country. As he wrote to his good friend James Monroe , “My God! How little do my countrymen know what precious blessings they are in possession of, and which no other people on earth enjoy.”

Jefferson arrived in Virginia in November 1789 to find George Washington waiting for him with news that Washington had been elected the first president of the United States of America and that he was appointing Jefferson as his secretary of state. Besides Jefferson, Washington’s most trusted advisor was Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton . A dozen years younger than Jefferson, Hamilton was a New Yorker and war hero who, unlike Jefferson and Washington, had risen from humble beginnings.

Rancorous partisan battles emerged to divide the new American government during Washington’s presidency. On one side, the Republican Party, led by Jefferson, promoted the supremacy of state governments, a strict constructionist interpretation of the U.S. Constitution , and support for the French Revolution . On the other side, the Federalists , led by Alexander Hamilton , advocated for a strong national government, broad interpretation of the Constitution, and neutrality in European affairs.

Washington’s two most trusted advisors thus provided nearly opposite advice on the most pressing issues of the day: the creation of a national bank, the appointment of federal judges, and the official posture toward France. On January 5, 1794, frustrated by the endless conflicts, Jefferson resigned as secretary of state, once again abandoning politics in favor of his family and farm at his beloved Monticello.

Despite Jefferson’s public ambivalence and previous claims that he was through with politics, the Republicans selected Jefferson as their candidate to succeed George Washington as president. In those days, candidates didn’t campaign for office openly, so Jefferson did little more than remain at home on the way to finishing a close second to then–Vice President John Adams in the electoral college vote. By the rules of the time, that made Jefferson the new vice president. He held the post from 1797 to 1801.

Besides presiding over the U.S. Senate , the vice president had essentially no substantive role in government. The long friendship between Adams and Jefferson had cooled due to political differences (Adams was a Federalist), and Adams didn’t consult his vice president on any important decisions.

To occupy his time during his four years as vice president, Jefferson authored A Manual of Parliamentary Practice , one of the most useful guides to legislative proceedings ever written, and served as the president of the American Philosophical Society.

John Adams ’ presidency revealed deep fissures in the Federalist Party between moderates such as Adams and George Washington and more extreme Federalists like Alexander Hamilton . In the presidential election of 1800, the Federalists refused to back Adams, clearing the way for the Republican candidates Jefferson and Aaron Burr to tie for first place, with 73 electoral votes each. After a long and contentious debate, the U.S. House of Representatives selected Jefferson to serve as the third president of America, with Burr as his vice president.

The election of Jefferson in 1800 was a landmark of world history: the first peacetime transfer of power from one party to another in a modern republic. Delivering his inaugural address on March 4, 1801, Jefferson spoke to the fundamental commonalities uniting all Americans despite their partisan differences. “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle,” he stated. “We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

President Jefferson’s accomplishments during his first term in office, from 1801 to 1805, were numerous, remarkably successful, and productive. In keeping with his Republican values, Jefferson stripped the presidency of all the trappings of European royalty, reduced the size of the armed forces and government bureaucracy, and lowered the national debt from $80 million to $57 million in his first two years in office.

Nevertheless, Jefferson’s most important achievements as president all involved bold assertions of national government power and surprisingly liberal readings of the Constitution.

Louisiana Purchase

Jefferson’s most significant accomplishment as president was the Louisiana Purchase. In 1803, he acquired land stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains from cash-strapped Napoleonic France for the bargain price of $15 million, thereby doubling the size of the nation in a single stroke. He then devised the wonderfully informative Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore, map out, and report back on the new American territories.

Tripoli Pirates

Jefferson also put an end to the centuries-old problem of Tripoli pirates from North Africa disrupting American shipping in the Mediterranean. During the Barbary War , Jefferson forced the pirates to capitulate by deploying new American warships.

Notably, both the Louisiana Purchase and the undeclared war against the Barbary pirates conflicted with Jefferson’s much-avowed Republican values. Both actions represented unprecedented expansions of national government power, and neither was explicitly sanctioned by the Constitution.

Second Term

Although Jefferson easily won re-election in 1804, his second term in office proved much more difficult and less productive than his first. He largely failed in his efforts to impeach the many Federalist judges swept into government by the Judiciary Act of 1801.

However, the greatest challenges of Jefferson’s second term were posed by the war between Napoleonic France and Great Britain. Both Britain and France attempted to prevent American commerce with the other power by harassing American shipping. Britain, in particular, sought to impress American sailors into the British Navy.

In response, Jefferson passed the Embargo Act of 1807, suspending all trade with Europe. The move wrecked the American economy as exports crashed from $108 million to $22 million by the time he left office in 1809. The embargo also led to the War of 1812 with Great Britain after Jefferson left office.

Jefferson was the first leader of the Republican Party, which formed in the 1790s and became the Democratic-Republican Party before the end of the decade. Jeffersonian Republicans advocated for a smaller federal government, encouraged states’ rights and individual liberties, and favored a strict interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. Jefferson was the first of three Democratic-Republican presidents, followed by James Madison and James Monroe . The party eventually evolved into the modern-day Democratic Party.

Beyond his positions and actions while in public office, Jefferson offered a window into his political philosophy and worldview through his only full-length book, Notes on the State of Virginia . He began writing the book in late 1781 after stepping down as the governor of Virginia and ostensibly sought to outline the history, culture, and geography of his home state. However, Notes on the State of Virginia also contained Jefferson’s vision of the good society he hoped America would become: a virtuous agricultural republic based on the values of liberty, honesty, and simplicity and centered on the self-sufficient yeoman farmer.

Views on Slavery

Jefferson’s writings shed light on his contradictory, controversial, and much-debated views on race and slavery . Jefferson was a slave owner his entire life, and his very existence as a gentleman farmer depended on the institution of slavery.

Like most white Americans of that time, Jefferson held views we would now describe as nakedly racist: He believed that Black people were innately inferior to white people in terms of both mental and physical capacity.

Nevertheless, he claimed to abhor slavery as a violation of the natural rights of man. He saw the eventual solution of America’s race problem as the abolition of slavery followed by the exile of formerly enslaved people to either Africa or Haiti, because, he believed, the formerly enslaved couldn’t live peacefully alongside their former masters.

As Jefferson wrote, “We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

Democratic Legacy

Jefferson will be forever revered as one of the great American Founding Fathers . As the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson wrote the foundational text of American democracy and one of the most important documents in world history. He also wrote about other key democratic ideals, including:

- The separation of church and state: In 1777, Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which established freedom of religion and the separation of church and state. Although the document wasn’t adopted as Virginia state law for another nine years, it was one of Jefferson’s proudest life accomplishments.

- Legislative procedures: Jefferson’s A Manual of Parliamentary Practice (1801) established more granular rules for America’s legislative bodies than had been previously outlined. He was inspired to study the subject while serving as vice president, which involved overseeing the U.S. Senate. His rules are still active influences in the Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives.

Ultimately, Jefferson was a man of many contradictions. He was the spokesman of liberty and a racist slave owner, a champion of the common people and a man with luxurious and aristocratic tastes, a believer in limited government and a president who expanded governmental authority beyond the wildest visions of his predecessors, a quiet man who abhorred politics and arguably the most dominant political figure of his generation. The tensions between Jefferson’s principles and practices make him all the more apt a symbol for the nation he helped create, a nation whose shining ideals have always been complicated by a complex history.

On March 4, 1809, after watching the inauguration of his close friend and successor James Madison , Jefferson returned to Virginia to live out the rest of his days as “The Sage of Monticello.”

His primary pastime was endlessly rebuilding, remodeling, and improving his home and estate, at considerable expense. A Frenchman named Marquis de Chastellux quipped, “it may be said that Mr. Jefferson is the first American who has consulted the Fine Arts to know how he should shelter himself from the weather.”

Jefferson also dedicated his later years to organizing the University of Virginia, the nation’s first secular university. He personally designed the campus, envisioned as an “academical village” in Charlottesville, and hand-selected renowned European scholars to serve as its professors. The University of Virginia opened its doors on March 7, 1825, one of the proudest days of Jefferson’s life.

At the end of his life, the former president kept up an outpouring of correspondence. In particular, he rekindled a lively correspondence on politics, philosophy, and literature with John Adams that stands out among the most extraordinary exchanges of letters in history.

Nevertheless, Jefferson’s retirement was marred by financial woes. To pay off the substantial debts he incurred over decades of living beyond his means, Jefferson resorted to selling his cherished personal library to the national government to serve as the foundation of the Library of Congress.

Jefferson died on July 4, 1826—the 50 th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence—at his Monticello estate near Charlottesville, Virginia.

His death occurred only a few hours before fellow Founding Father John Adams passed away in Massachusetts. In the moments before he passed, Adams spoke his last words, eternally true though not in the literal sense he meant them: “Thomas Jefferson survives.”

Jefferson is buried in the family cemetery at his beloved Monticello, in a grave marked by a plain gray tombstone. The brief inscription it bears, written by Jefferson, himself, is as noteworthy for what it excludes as what it includes. It suggests his humility as well as his belief that his greatest gifts to posterity came in the realm of ideas rather than the realm of politics:

“Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and father of the University Of Virginia.”

The former president’s likeness appears on the U.S. nickel and on Mount Rushmore. The Thomas Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 1943 and took architectural influence from Jefferson’s designs at Monticello and the University of Virginia.

- We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.

- All tyranny needs to gain a foothold is for people of good conscience to remain silent.

- How little do my countrymen know what precious blessings they are in possession of, and which no other people on earth enjoy.

- Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.

- The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground.

- I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.

- I find friendship to be like wine, raw when new, ripened with age, the true old man’s milk and restorative cordial.

- I cannot live without books; but fewer will suffice where amusement, and not use, is the only future object.

- The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.

- All, too, will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will to be rightful must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal law must protect, and to violate would be oppression.

- I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.

- [A] wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.

- I know well that no man will ever bring out of that office the reputation which carries him into it.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

U.S. Presidents

Donald Trump

President Joe Biden’s Life in Photos

A History of Presidential Assassination Attempts

Ronald Reagan

How Ronald Reagan Went from Movies to Politics

Teddy Roosevelt’s Stolen Watch Recovered by FBI

Franklin D. Roosevelt

A Car Accident Killed Joe Biden’s Wife and Baby

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

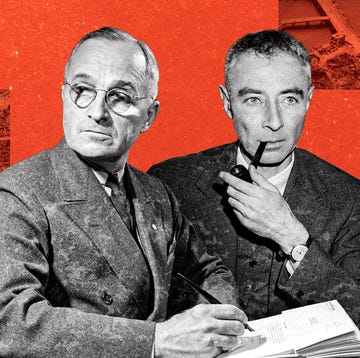

Oppenheimer and Truman Met Once. It Went Badly.

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

John F. Kennedy

Biography Online

Biography Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743–July 4, 1826) was a leading Founding Father of the United States, the author of the Declaration of Independence (1776) and he served as the third President of the US (1801–1809). Jefferson was a committed Republican – arguing passionately for liberty, democracy and devolved power. Jefferson also wrote the Statute for Religious Freedom in 1777 – it was adopted by the state of Virginia in 1786. Jefferson was also a noted polymath with wide-ranging interests from architecture to gardening, philosophy, literature and education. Although a slave owner himself, Jefferson sought to introduce a bill (1800) to end slavery in all Western territories. As President, he signed a bill to ban the importation of slaves into the US (1807).

Jefferson’s Childhood

“Still less let it be proposed that our properties within our own territories shall be taxed or regulated by any power on earth but our own. The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them. This, sire, is our last, our determined resolution;”

Thomas Jefferson – A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774). ( Wikisource )

Thomas Jefferson and The Declaration of Independence (1776)

Thomas Jefferson was the primary author in drafting the American Declaration of Independence. The act was adopted on July 4th, 1776 and was a symbolic statement of the aims of the American Revolution.

“We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness…”

– Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence , July 4th, 1776. Jefferson received suggestions from others such as James Madison. He was also influenced by the writings of the British Empiricists, in particular, John Locke and Thomas Paine . The importance of the Declaration of Independence was summed up in The Gettysburg address of Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

However, Jefferson was disappointed that a reference to the evil of slavery was removed at the request of delegates from the South. From 1785 to 1789 Jefferson served as minister to France, succeeding Benjamin Franklin . In France, Jefferson became immersed in Paris society. He was a noted host and came into contact with many of the great thinkers of the age. Jefferson also saw the social and political turmoil which resulted in the French Revolution. On 26 August 1789, the French Assembly published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , which was directly influenced by Jefferson’s US Declaration of Independence. On his return to America Jefferson served under George Washington as first Secretary of State. Here he began debating with the Hamilton factions over the size of government spending. Jefferson was an advocate of minimal government. At the end of his term 1783, he retired temporarily to Monticello, where he spent time amongst his gardens and with his family.

Jefferson – President in 1800

In 1796 Jefferson stood for President but lost narrowly to John Adams ; however, under the terms of the constitution, this was sufficient for him to become Vice President. In the run-up to the next election of 1800 Jefferson fought a bitter campaign. In particular, the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798 led to the imprisonment of many newspaper editors who supported Jefferson and were critical of the existing government. However, Jefferson was narrowly elected and this allowed him to promote open and representative government. On being elected, he offered a hand of friendship to his former political enemies. He also allowed the Sedition Act to expire and promoted the practical existence of free speech. The Presidency of Jefferson was eventful, but importantly he was able to preside over a period of relative stability and generally kept America out of conflict.

“I love peace, and am anxious that we should give the world still another useful lesson, by showing to them other modes of punishing injuries than by war, which is as much a punishment to the punisher as to the sufferer.”

At the time American neutrality was imperilled by the British-French wars, which raged around Canada. In 1803 Jefferson was able to double the size of the US, through the Louisiana Purchase, which gave America many states to the west. He also commissioned the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which crossed America seeking to explore and create friendships with the Native American populations.

Jefferson’s Retirement in Monticello

Thomas Jefferson’s Personal Life

Thomas Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton in 1772. Together they had six children, including one stillborn son. Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772–1836), Jane Randolph (1774–1775), a stillborn or unnamed son (1777), Mary Wayles (1778–1804), Lucy Elizabeth (1780–1781), and Lucy Elizabeth (1782–1785). Martha died only 10 years later. Thomas Jefferson remained single for the rest of his life. It was alleged that Jefferson fathered some of Sally Hemings’ daughters. Jefferson never denied it in public, but he did deny it private correspondence. There has never been any conclusive proof that this occurred.

Personal qualities

Jefferson was over 6’2″; this was very tall for his age. He didn’t relish public speaking, he preferred to express his opinions through his writings. His friends and family remarked on Jefferson’s many fine qualities. He was sympathetic and engaging in conversation. Never bored, he always found different avenues of interest to explore. Thomas Jefferson left a profound mark on America, through his influential shaping of the American constitution and political practices. Jefferson died at the age of 84 on the afternoon of July 4; it was the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. A few hours later on the same day, his longtime friend and fellow Founding Father John Adams also passed away. On his tombstone, Jefferson had inscribed three achievements he was proudest of:

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Thomas Jefferson ”, Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net . Published 22 June 2014 Last updated 22 October 2019.

Thomas Jefferson: A Life

Thomas Jefferson: A Life at Amazon

Light and Liberty – Quotes of Thomas Jefferson

Light and Liberty – Quotes of Thomas Jefferson at Amazon

Related pages

- Thomas Jefferson – Achievements

- Thomas Jefferson – minor accomplishments

- Thomas Jefferson’s views on religion

External Links

- Thomas Jefferson – Light and Liberty

- Monticello – The home of Thomas Jefferson

- Grounds & Garden

- First Ladies

- VP Residence

- Historical Tour

- African-American History Month

- Presidents & Baseball

- Grounds and Garden

- Easter Egg Roll

- Christmas & Holidays

- State of the Union

- Historical Association

- Presidential Libraries

- Air Force One

Presidents by Name

Presidents by Date

View Flash Version