- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

A research paper is a detailed academic document that presents the results of a study or investigation. It involves critical analysis, evidence-based arguments, and a thorough exploration of a specific topic. Writing a research paper requires following a structured format to ensure clarity, coherence, and academic rigor. This article explains the structure of a research paper, provides examples, and offers a practical writing guide.

Research Paper

A research paper is a formal document that reports on original research or synthesizes existing knowledge on a specific topic. It aims to explore a research question, present findings, and contribute to the broader field of study.

For example, a research paper in environmental science may investigate the effects of urbanization on local biodiversity, presenting data and interpretations supported by credible sources.

Importance of Research Papers

- Knowledge Contribution: Adds to the academic or professional understanding of a subject.

- Skill Development: Enhances critical thinking, analytical, and writing skills.

- Evidence-Based Arguments: Encourages the use of reliable sources to support claims.

- Professional Recognition: Serves as a medium for sharing findings with peers and stakeholders.

Structure of a Research Paper

1. title page.

The title page includes the paper’s title, author’s name(s), affiliation(s), and submission date.

- Title: “The Impact of Remote Work on Employee Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic”

- Author: Jane Doe

- Affiliation: XYZ University

2. Abstract

A concise summary of the research, typically 150–300 words, covering the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Example: “This study examines the effects of remote work on employee productivity. Data collected from surveys and interviews revealed that productivity increased for 65% of respondents, primarily due to flexible schedules and reduced commuting times.”

3. Introduction

The introduction sets the context for the research, explains its significance, and presents the research question or hypothesis.

- Background information.

- Problem statement.

- Objectives and research questions.

- Example: “With the rapid shift to remote work during the pandemic, understanding its impact on productivity has become crucial. This study aims to explore the benefits and challenges of remote work in various industries.”

4. Literature Review

The literature review summarizes and critiques existing research, identifying gaps that the current study addresses.

- Overview of relevant studies.

- Theoretical frameworks.

- Research gaps.

- Example: “Previous studies highlight improved flexibility in remote work but lack comprehensive insights into its impact on team collaboration and long-term productivity.”

5. Methodology

This section explains how the research was conducted, ensuring transparency and replicability.

- Research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods).

- Data collection methods (surveys, interviews, experiments).

- Data analysis techniques.

- Ethical considerations.

- Example: “A mixed-methods approach was adopted, using online surveys to collect quantitative data from 200 employees and semi-structured interviews with 20 managers to gather qualitative insights.”

The results section presents the findings of the research in an objective manner, often using tables, graphs, or charts.

- Example: “Survey results indicated that 70% of employees reported higher job satisfaction, while 40% experienced challenges with communication.”

7. Discussion

This section interprets the results, relates them to the research questions, and compares them with findings from previous studies.

- Analysis and interpretation.

- Implications of the findings.

- Limitations of the study.

- Example: “The findings suggest that while remote work enhances individual productivity, it poses challenges for team-based tasks, highlighting the need for improved communication tools.”

8. Conclusion

The conclusion summarizes the key findings, emphasizes their significance, and suggests future research directions.

- Example: “This study demonstrates that remote work can enhance productivity, but organizations must address communication barriers to maximize its benefits. Future research should focus on sector-specific impacts of remote work.”

9. References

A list of all the sources cited in the paper, formatted according to the required style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago).

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . Sage Publications.

10. Appendices

Supplementary materials, such as raw data, survey questionnaires, or additional analyses, are included here.

Examples of Research Papers

1. education.

Title: “The Effectiveness of Interactive Learning Tools in Enhancing Student Engagement”

- Abstract: Summarizes findings that interactive tools like Kahoot and Quizlet improved engagement by 45% in middle school classrooms.

- Methods: Quantitative surveys with 300 students and qualitative interviews with 15 teachers.

2. Healthcare

Title: “Telemedicine in Rural Healthcare: Opportunities and Challenges”

- Abstract: Highlights how telemedicine improved access to healthcare for 80% of surveyed rural residents, despite connectivity issues.

- Methods: Mixed methods involving patient surveys and interviews with healthcare providers.

3. Business

Title: “The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Customer Experience”

- Abstract: Discusses how AI tools like chatbots reduced response times by 30%, improving customer satisfaction in the e-commerce sector.

- Methods: Case studies of three leading e-commerce companies and customer feedback analysis.

Writing Guide for a Research Paper

Step 1: choose a topic.

Select a topic that aligns with your interests, is relevant to your field, and has sufficient scope for research.

Step 2: Conduct Preliminary Research

Review existing literature to understand the context and identify research gaps.

Step 3: Develop a Thesis Statement

Formulate a clear and concise statement summarizing the main argument or purpose of your research.

Step 4: Create an Outline

Organize your ideas and structure your paper into sections, ensuring a logical flow.

Step 5: Write the First Draft

Focus on content rather than perfection. Start with the sections you find easiest to write.

Step 6: Edit and Revise

Review for clarity, coherence, grammar, and adherence to formatting guidelines. Seek feedback from peers or mentors.

Step 7: Format and Finalize

Ensure your paper complies with the required citation style and formatting rules.

Tips for Writing an Effective Research Paper

- Be Clear and Concise: Avoid jargon and lengthy explanations; focus on delivering clear arguments.

- Use Credible Sources: Rely on peer-reviewed articles, books, and authoritative data.

- Follow a Logical Structure: Maintain a coherent flow from introduction to conclusion.

- Use Visual Aids: Include tables, charts, and graphs to summarize data effectively.

- Cite Sources Properly: Avoid plagiarism by adhering to proper citation standards.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Lack of Focus: A vague or overly broad topic can weaken the paper’s impact.

- Poor Organization: A disorganized structure makes the paper hard to follow.

- Inadequate Analysis: Merely presenting data without interpreting its significance undermines the paper’s value.

- Ignoring Guidelines: Failing to meet formatting or citation requirements can detract from professionalism.

A research paper is a critical academic tool that requires careful planning, organization, and execution. By following a clear structure that includes essential components like the introduction, methodology, results, and discussion, researchers can effectively communicate their findings. Understanding the elements and employing best practices ensures a well-crafted and impactful research paper that contributes meaningfully to the field.

- Babbie, E. (2020). The Practice of Social Research . Cengage Learning.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods . Oxford University Press.

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., & Williams, J. M. (2016). The Craft of Research . University of Chicago Press.

- APA (2020). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). American Psychological Association.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and...

Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Structure of a Research Paper

Structure of a Research Paper: IMRaD Format

I. The Title Page

- Title: Tells the reader what to expect in the paper.

- Author(s): Most papers are written by one or two primary authors. The remaining authors have reviewed the work and/or aided in study design or data analysis (International Committee of Medical Editors, 1997). Check the Instructions to Authors for the target journal for specifics about authorship.

- Keywords [according to the journal]

- Corresponding Author: Full name and affiliation for the primary contact author for persons who have questions about the research.

- Financial & Equipment Support [if needed]: Specific information about organizations, agencies, or companies that supported the research.

- Conflicts of Interest [if needed]: List and explain any conflicts of interest.

II. Abstract: “Structured abstract” has become the standard for research papers (introduction, objective, methods, results and conclusions), while reviews, case reports and other articles have non-structured abstracts. The abstract should be a summary/synopsis of the paper.

III. Introduction: The “why did you do the study”; setting the scene or laying the foundation or background for the paper.

IV. Methods: The “how did you do the study.” Describe the --

- Context and setting of the study

- Specify the study design

- Population (patients, etc. if applicable)

- Sampling strategy

- Intervention (if applicable)

- Identify the main study variables

- Data collection instruments and procedures

- Outline analysis methods

V. Results: The “what did you find” --

- Report on data collection and/or recruitment

- Participants (demographic, clinical condition, etc.)

- Present key findings with respect to the central research question

- Secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

VI. Discussion: Place for interpreting the results

- Main findings of the study

- Discuss the main results with reference to previous research

- Policy and practice implications of the results

- Strengths and limitations of the study

VII. Conclusions: [occasionally optional or not required]. Do not reiterate the data or discussion. Can state hunches, inferences or speculations. Offer perspectives for future work.

VIII. Acknowledgements: Names people who contributed to the work, but did not contribute sufficiently to earn authorship. You must have permission from any individuals mentioned in the acknowledgements sections.

IX. References: Complete citations for any articles or other materials referenced in the text of the article.

- IMRD Cheatsheet (Carnegie Mellon) pdf.

- Adewasi, D. (2021 June 14). What Is IMRaD? IMRaD Format in Simple Terms! . Scientific-editing.info.

- Nair, P.K.R., Nair, V.D. (2014). Organization of a Research Paper: The IMRAD Format. In: Scientific Writing and Communication in Agriculture and Natural Resources. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03101-9_2

- Sollaci, L. B., & Pereira, M. G. (2004). The introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) structure: a fifty-year survey. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA , 92 (3), 364–367.

- Cuschieri, S., Grech, V., & Savona-Ventura, C. (2019). WASP (Write a Scientific Paper): Structuring a scientific paper. Early human development , 128 , 114–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.09.011

- Topics Analyze Data Regression Analysis Machine Learning and Predictive Modeling Tests Causal Inference Manage and Manipulate Data Manipulating and Cleaning Data Loading and Importing Data Visualizing and Reporting Data Visualization Reporting Tables Computer Setup Developing Coding Skills Software Installation Automations and Workflows Version Control and Repository Management Using Artificial Intelligence Replicability and Environment Management Automation Tools Workflows Collect & Store Data Storage Data Collection Collaborate and Share Project Management and Team Sciences Share your Work Research Skills & Theses Writing an academic paper Organizing your Research Templates and Dynamic Documents

- Examples Exploring Trends in the Cars Dataset with Regression Analysis A Reproducible Workflow Using Snakemake and R A Simple Reproducible Research Workflow A Simple Reproducible Web Scraping Example A Primer on Bayesian Inference for Accounting Research A Reproducible Research Workflow with AirBnB Data Find Keywords and Sentences from Multiple PDF Files An Interactive Shiny App of Google's COVID-19 Data

- About About Tilburg Science Hub Meet our contributors Visit our blog

Personalized Cookies

Full content

Want to know more? Check our Disclaimer .

Chapter Structure of a Thesis or Academic Paper

Join the community! Visit our GitHub or LinkedIn page to join the Tilburg Science Hub community, or check out our contributors' Hall of Fame ! Want to change something or add new content? Click the Contribute button!

The typical structure of an empirical paper, a master or Ph.D. thesis in economics and business involves the following sections:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Institutional background

Conceptual framework

- Online appendix

The outline is discussed chapter-by-chapter. Keep in mind that the chapter structure/order might slightly differ depending on your official formatting guidelines, but the content should be more or less in the same order.

Be as brief as possible and avoid word-by-word duplication with the introduction. State very clearly what the main take-away is for your paper. This can be a qualitative finding, but it can also be a number.

There is not one structure that always works, but here's a structured approach that is well-suited as a starting point:

- Implicit research question Begin your introduction by providing a general motivation for your paper, introducing the reader to the topic and establishing the importance of the practical problem.

Subsequently, implicitly state your research question. Instead of saying "My research question is: "What is the effect of X on Y?" , state it as "Therefore, it is crucial to understand ..."

For refining your research question, check out the topic on Preparation for your Thesis .

- Motivate your research question

Explain why it this topic is important and interesting. Think about using economic factors, social or political implications, or evidence relevance to top management, to convince the reader of the importance. Example sentences are "Studying the effect of X on Y is crucial to.." , or "The effect of X on Y is worth studying because.."

Literature review : Briefly summarize the relevant literature (not all the literature) and explain in detail how you contribute to it with your paper.

Briefly explain your data, methods, and results. : Give an overview of what data you are using, with what methods you will study the research question, and what the results are.

The outline of the next chapters : Describe what sections will come after the introduction.

Look at other (similar) papers as an example on how to phrase what you want to say.

The literature review is included in the introduction or has its own chapter right after the introduction. It serves to explain existing research, what is missing and what your contribution will be. A good approach is to keep the order as of answering these three questions:

What is known already? Explain what other studies say about your topic and show connections between your work and theirs. Example sentences are: “My research relates to extant literature in the following ways..."/"My research contributes to the following literature..." Rather than just giving a summary, give a "synthesis" of existing literature.

What do we not know? Identify the gap in relevant literature. On what does existing literature miss out?

What is your contribution? Explain how your thesis adds to the existing knowledge. E.g. a new problem, new data, new theory, or a new method. Revise the Preparation section to see how you can best formulate your contribution. Example sentences are: “Our research extends extant research by…” , or “Therefore, as a first contribution, we ...” .

Creating a table to categorize existing literature alongside your contribution can provide a clear visual representation of how your research adds value to the existing knowledge.

Institutional Background

The institutional background aims to provide contextual information within which your research takes place. It can include details about the institution, organization, or broader socio-economic factors that might influence or impact the subject under investigation. Be brief and focus on what is relevant for your study. Provide one or a few references. Don't go too much into the details unless necessary.

This chapter explains the hypothesized relationship between X (the covariates) and Y (the dependent variable) by grounding it in existing theory or your own logical reasoning.

Moreover, consider alternative arguments: while X may predominantly suggest a positive relationship, it's valuable to think about potential scenarios where it could demonstrate a negative correlation.

Start this section with presenting your argumentation and end by explicitly stating your hypothesis. A hypothesis outlining the direction of the effect (looking for causality ) is much stronger than just hypothesizing there is an effect.

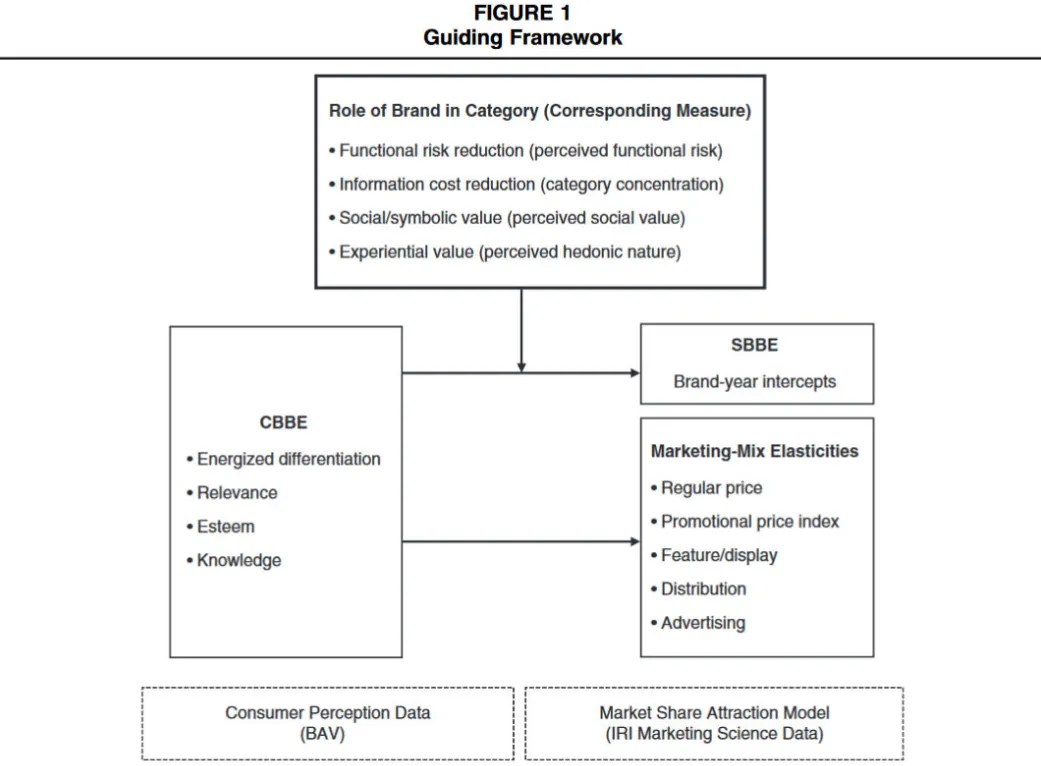

Visualizing your framework

Integrating a visual representation of your conceptual framework makes it easier to understand (for you and the reader!).

Example of a conceptual diagram

Below is an example of a conceptual framework in the field of Marketing.

Datta, H., Foubert, B., & Van Heerde, H. J. (2015). The challenge of retaining customers acquired with free trials. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(2), 217-234.

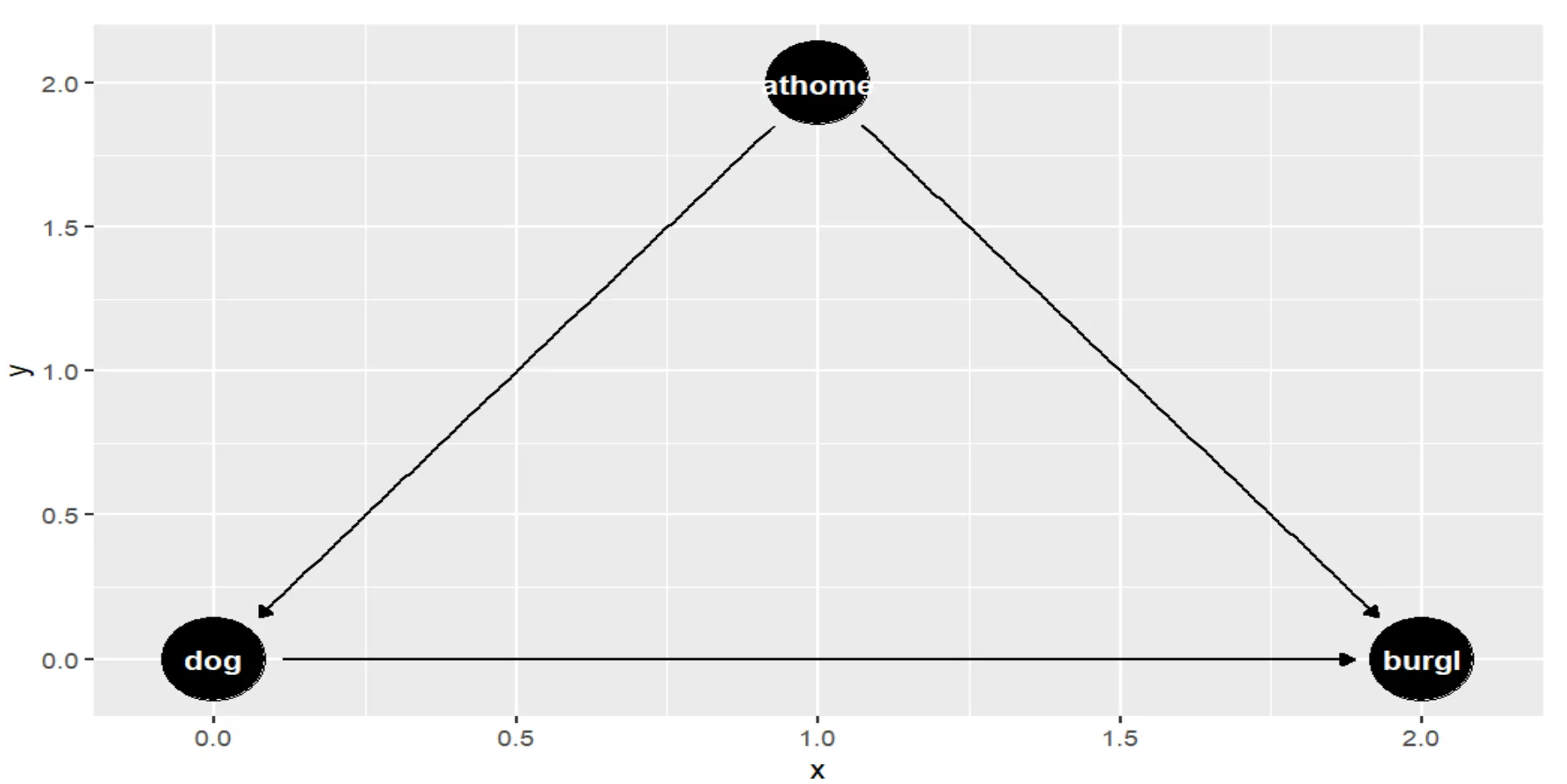

Causal diagram

A causal diagram can help to clarify which covariates are relevant and in which way they relate to the main variables (moderators/confounders). Causality specifies the direction of the effect, you are looking for more than just correlation, which is usually what research questions in economics-related fields are about.

Below is an example of a causal diagram created using R, illustrating the causal relationship between owning a dog and the likelihood of experiencing a burglary. There is the confounding factor of being at home often.

Hypothesis or expectation

If you have a strong theory, you can cleanly predict what happens to Y if you change X. In that case, it makes most sense having formal hypotheses in your paper. For example, see Datta, Foubert and van Heerde (2015, JMR, https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.12.0160 )

If your theory is not strong, or your predictions are frequently going in both ways (e.g., both positive and negative), it is better to keep it to expectations , rather than writing out hypotheses. An example paper having expectations is Datta, Ailawadi , and Van Heerde (2017) .

Alternatively, a paper can very well do without any hypotheses or expectations. See the example of Datta, Knox, and Bronnenberg (2018) .

The most important thing is that you choose a format that fits your research!

In this chapter, you explain which data you use and what you do to construct your estimation sample. Put additional details into an appendix or the online appendix. Provide meaningful summary statistics that are closely related to the analysis you will do. Spend time on thinking what is really relevant for the reader.

The Data chapter typically consists of the following parts: - Description of data collection and raw data - Data preparation: raw to final data - Descriptive statistics of the final dataset

1. Description of data collection and raw data

Describe how the raw data was stored, or how you gathered it yourself (e.g. with webscraping or APIs).

The primary key : this is the unique identifier for each entity within the dataset. For instance, in analyzing YouTube views per video, the primary key might be "video_id - day". Similarly, when analyzing income distribution across households, the primary key could be a "household ID".

Frequency : This specifies the interval or frequency at which data is recorded - whether it's every 5 years, annually, monthly, daily, or at a finer granularity like minutes or seconds.

Value columns: These columns hold data recorded per primary key. For example, YouTube views per video or economic attributes such as income levels and demographic details of households.

Summary statistics for raw data

A descriptive statistics table with mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum per variable is essential.

2. Data preparation

Before analyzing the data, cleaning and transforming the raw data is necessary. Typical things to include about the data preparation are: - Refinement of sample : Describe how you refined or filtered the dataset, specifying inclusion or exclusion criteria. - Explain your approach to handle missing values and outliers - Aggregate your data : E.g. converting monthly data to yearly. - Data merging : Integrating data from different sources into one dataset that contains all the variables you need for analysis.

Operationalization of variables : Define the variables to be used and illustrate how certain variables were computed or transformed. Provide a table if necessary.

Look into existing literature to see how previous researchers have defined variables that you are looking for.

3. Descriptive statistics of the final dataset

Present a table of summary statistics of the final dataset, including key metrics per variable. Also, provide plots to visualize and highlight interesting trends or aspects. Even before model estimation, you can highlight a certain trend between two variables.

The Data visualization building block teaches the best practices.

Write this section such that a graduate student with general training could run the analysis if you give him the data. Typically, you will describe your model in a formula, and an accompanying text. Draw inspiration from existing literature on this particular research method and how to define it. Pay attention to the correct sub indices!

Regression models

For regression models, there are some good resources at Tilburg Science Hub to help you in the analysis and model selection:

The basics of regression analysis : A building block on how to estimate a model with regression analysis and make predictions on the relationship between variables.

Regression with panel data : A series that includes several methods for panel data analysis, and helps you to choose between a fixed and random effects model.

- An introduction to Instrumental Variable regression

- An introduction to Difference-in-Difference analysis

- A series on Regression Discontinuity Design

- An introduction to the Synthetic Control Method

Think hard about how to present and discuss the results. Make a careful selection. For each table and figure, ask yourself what exactly it is meant to convey to the reader.

Results table

Report your estimation results in a table. Don't just copy this from your statistical software. You might want a table combining multiple models or making other adjustments, e.g. like adding fit metrics to the table, or deleting controls not relevant to mention.

Learn here how to create a ready-to-use LaTeX regression table in R.

Metrics about the model

Also report appropriate metrics about your model such as the R-squared, adjusted R-squared, F-test (for regressions), log-likelihood test (for Logit models), and any validation conducted on a holdout sample.

If you've explored competing models, showcase the fit statistics for each model and provide reasoning behind your final model selection.

Diagnostic plots

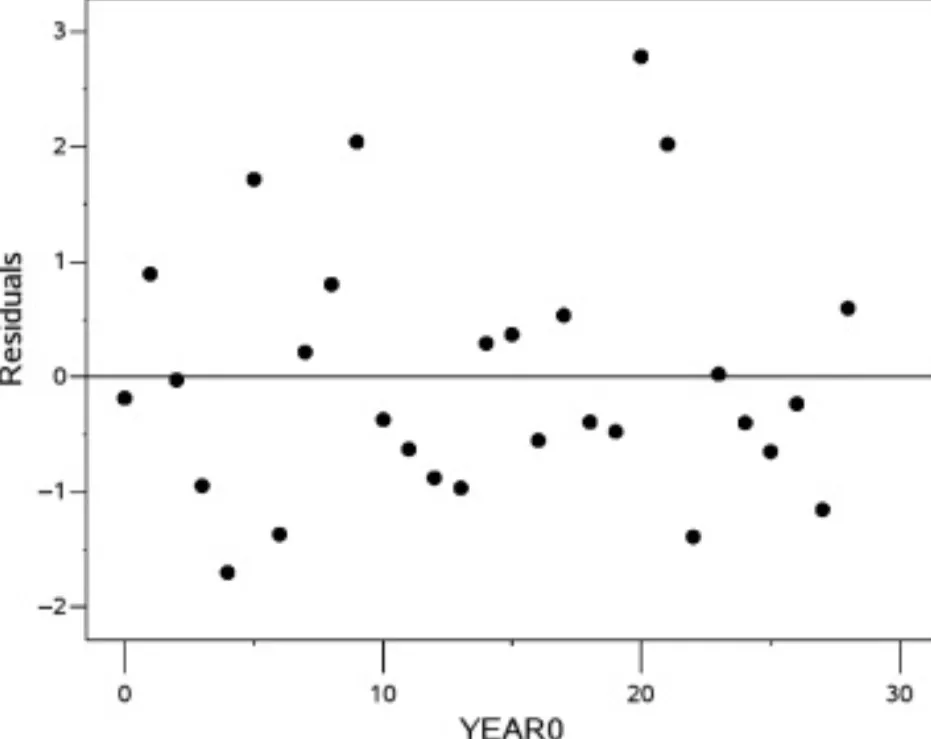

Think about adding a diagnostic plot to serve as a visual tool to assess the adequacy and assumptions of the model fit. Which kind of plot really depends on your type of model.

An example for a linear regression model is a residual plot . Here, the independent variable is YEAR0 = (year-1990) and the residuals represent the expected temperature for the year 1990. A random scatter of points indicates that the residuals are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) and the assumption holds.

Explain your results

For each hypothesis tested in the study, follow these steps to report the findings: - Restate the hypothesis briefly. - Report the obtained result within brackets, including the coefficient and the significance level. For example, "The effect of A on B is statistically significant (β = xx, p = .012)" or "A increases B by x% (β = xx, p = .025)". - Explain the result: - For confirmed hypotheses, provide reasoning that reinforces your hypothesis. For instance, "As hypothesized, A leads to B because..." - For unconfirmed hypotheses, elaborate on this as well. It could be due to conceptual reasons (if the effect might not exist, provide arguments), measurement issues, or other relevant factors impacting the expected relationship. - Discuss the impacts of control variables. For example, "Control variables like age and gender exhibit observable effects. For instance, age positively influences the intention to purchase (β = xx, p = .12). However, education does not significantly predict intention to purchase (β = xx, p = .63). This lack of significance might be due to..."

Exact p-values Report the exact p-values in the text and tables. For example, p = 0.049 instead of p < 0.05. Also, the p-value needs to be written in italic.

Visualize your results

Consider plotting some results, e.g. relevant coefficients of your estimated models.

- Start by giving a concise summary of your main findings . You can also have a summary table with your results (e.g., hypotheses/expectations, confirmed/not confirmed, etc.).

- Discuss the implications of your findings . Elaborate on how the results challenge existing theories and their real-word implications for relevant stakeholders. Provide theoretical and managerial takeaways, or policy recommendations that elucidate the practical relevance of your research findings.

- Address the limitations in your research design. This demonstrates a nuanced understanding of the study's scope and potential constraints.Try to address all the concerns people may have. Don't be too defensive, but stay honest.

- You can include some robustness testing , where you examin the reliability of the results by conducting various sensitivity analyses or alternative methods.

- Suggest possibilities for future research based on the identified limitations or unanswered questions arising from your study.

- Briefly mention the main takeaways and their interpretations . Emphasize the significance of these findings in addressing the research objectives.

- Summarize any policy or business recommendations stemming from your research findings. Highlight actionable insights derived from the study that could be practically implemented or considered by policymakers or business stakeholders.

Learn here how to build and maintain a reference list effectively.

The appendix includes supplementary information that supports the main content but might be too detailed or lengthy to include in the main body of the paper.

Online Appendix

The online appendix serves as a repository for additional materials that complement the main content of the document. It's a place for extra datasets, tables, figures, or any information that enhances the understanding of the paper but might disrupt the flow if included within the main body.

Related Posts

Prepare for your master thesis.

The preparation phase of your thesis includes finding a good research question and investing in useful skills you will use during the thesis

Mastering Academic Writing

Learn strategies for academic writing, formatting, and referencing to ensure clear presentation of your research within your academic paper or thesis.

Master Thesis Resource Bundle

The Master Thesis Guide will serve as a guidance throughout the whole writing process of a thesis that consists of an empirical research project, for studies in marketing, economics, management, etc..

How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

Composing the Sections of a Research Paper

Cite this chapter.

7611 Accesses

4 Altmetric

To deliver content with the least distractions, scientific papers have a stereotyped form and style. The standard format of a research paper has six sections:

Title and Abstract , which encapsulate the paper

Introduction , which describes where the paper's research question fits into current science

Materials and Methods , which translates the research question into a detailed recipe of operations

Results , which is an orderly compilation of the data observed after following the research recipe

Discussion , which consolidates the data and connects it to the data of other researchers

Conclusion , which gives the one or two scientific points to which the entire paper leads

This format has been called the IMRAD (Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, And Discussion) organization. I,M,R,D is the order that the sections have in the published paper, but this is not the best order in which to write your manuscript. It is more efficient to work on the draft of your paper from the middle out, from the known to the discovered, i.e.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Books and Chapters in Books

How to Write a Scientific Paper

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

(2009). Composing the Sections of a Research Paper. In: From Research to Manuscript. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9467-5_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9467-5_7

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-1-4020-9466-8

Online ISBN : 978-1-4020-9467-5

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Training videos | Faqs

Research Paper Structure – Main Sections and Parts of a Research Paper

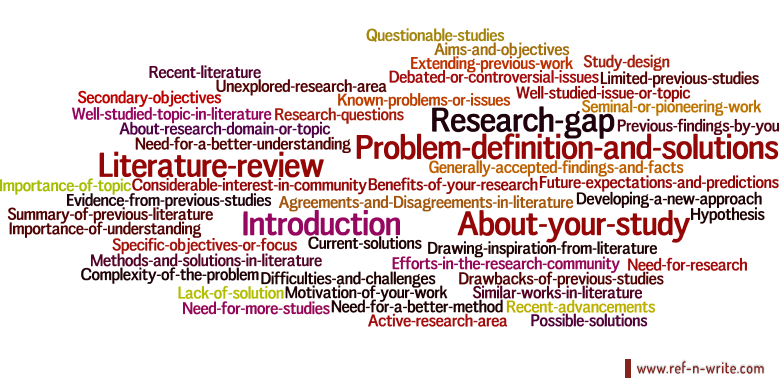

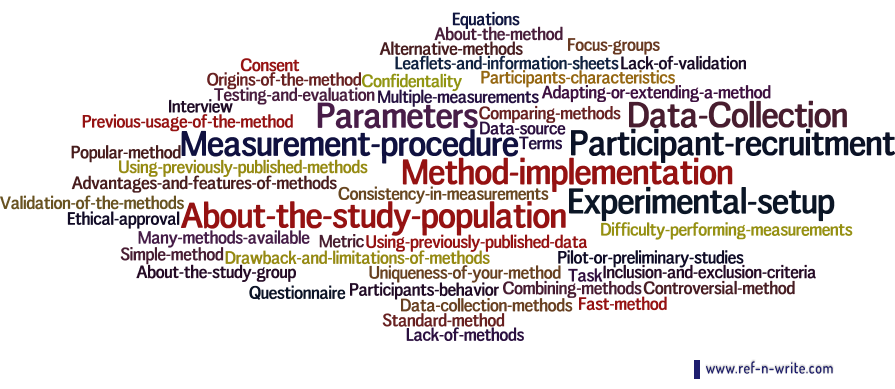

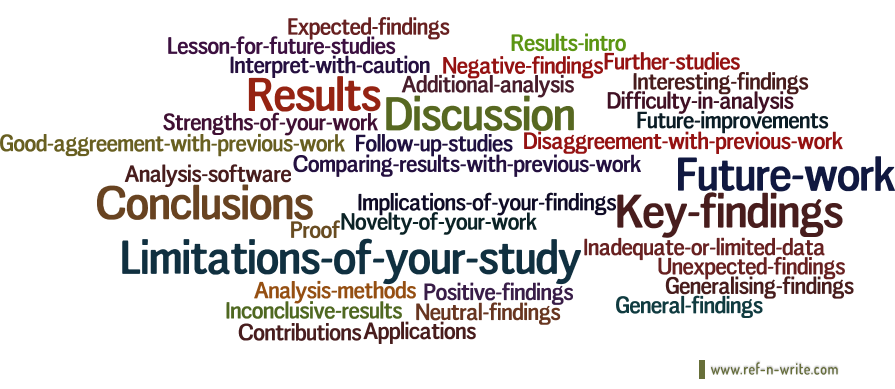

PhD students are expected to write and publish research papers to validate their research work and findings. Writing your first research paper can seem like a daunting task at the start but must be done to validate your work. If you are a beginner writer new to academic writing or a non-native English speaker then it might seem like a daunting process at inception. The best way to begin writing a research paper is to learn about the research paper structure needed in your field, as this may vary between fields. Producing a research paper structure first with various headings and subheadings will significantly simplify the writing process. In this blog, we explain the basic structure of a research paper and explain its various components. We elaborate on various parts and sections of a research paper. We also provide guidance to produce a research paper structure for your work through word cloud diagrams that illustrate various topics and sub-topics to be included under each section. We recommend you to refer to our other blogs on academic writing tools , academic writing resources , and academic phrase-bank , which are relevant to the topic discussed in this blog.

1. Introduction

The Introduction section is one of the most important sections of a research paper. The introduction section should start with a brief outline of the topic and then explain the nature of the problem at hand and why it is crucial to resolve this issue. This section should contain a literature review that provides relevant background information about the topic. The literature review should touch upon seminal and pioneering works in the field and the most recent studies pertinent to your work.

The literature review should end with a few lines about the research gap in the chosen domain. This is where you explain the lack of adequate research about your chosen topic and make a case for the need for more research. This is an excellent place to define the research question or hypothesis. The last part of the introduction should be about your work. Having established the research gap now, you have to explain how you intend to solve the problem and subsequently introduce your approach. You should provide a clear outline that includes both the primary and secondary aims/objectives of your work. You can end the section by providing how the rest of the paper is organized. When you are working on the research paper structure use the word cloud diagrams as a guidance.

2. Material and Methods

The Materials and methods section of the research paper should include detailed information about the implementation details of your method. This should be written in such a way that it is reproducible by any person conducting research in the same field. This section should include all the technical details of the experimental setup, measurement procedure, and parameters of interest. It should also include details of how the methods were validated and tested prior to their use. It is recommended to use equations, figures, and tables to explain the workings of the method proposed. Add placeholders for figures and tables with dummy titles while working on the research paper structure.

Suppose your methodology involves data collection and recruitment. In that case, you should provide information about the sample size, population characteristics, interview process, and recruitment methods. It should also include the details of the consenting procedure and inclusion and exclusion criteria. This section can end with various statistical methods used for data analysis and significance testing.

3. Results and Discussion

Results and Discussion section of the research paper should be the concluding part of your research paper. In the results section, you can explain your experiments’ outcome by presenting adequate scientific data to back up your conclusions. You must interpret the scientific data to your readers by highlighting the key findings of your work. You also provide information on any negative and unexpected findings that came out of your work. It is vital to present the data in an unbiased manner. You should also explain how the current results compare with previously published data from similar works in the literature.

In the discussion section, you should summarize your work and explain how the research work objectives were achieved. You can highlight the benefits your work will bring to the overall scientific community and potential practical applications. You must not introduce any new information in this section; you can only discuss things that have already been mentioned in the paper. The discussion section must talk about your work’s limitations; no scientific work is perfect, and some drawbacks are expected. If there are any inconclusive results in your work, you can present your theories about what might have caused it. You have to end your paper with conclusions and future work . In conclusion, you can restate your aims and objectives and summarize your main findings, preferably in two or three lines. You should also lay out your plans for future work and explain how further research will benefit the research domain. Finally, you can also add ‘Acknowledgments’ and ‘References’ sections to the research paper structure for completion.

Similar Posts

How to Create a Research Paper Outline?

In this blog we will see how to create a research paper outline and start writing your research paper.

Writing a Questionnaire Survey Research Paper – Example & Format

In this blog, we will explain how to write a survey questionnaire paper and discuss all the important points to consider while writing the research paper.

Materials and Methods Examples and Writing Tips

In this blog, we will go through many materials and methods examples and understand how to write a clear and concise method section for your research paper.

Formulating Strong Research Questions: Examples and Writing Tips

In this blog, we will go through many research question examples and understand how to construct a strong research question for your paper.

Examples of Good and Bad Research Questions

In this blog, we will look at some examples of good and bad research questions and learn how to formulate a strong research question.

Introduction Paragraph Examples and Writing Tips

In this blog, we will go through a few introduction paragraph examples and understand how to construct a great introduction paragraph for your research paper.

Useful. Thanks.

Thanks your effort of writting research

well articulated

Thank you author

Most usefull to write research article and publish in standard journal

Thank you for the write up. I have really learnt a lot.

Thanks for your efforts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- 26 Share Facebook

- 20 Share Twitter

- 8 Share LinkedIn

- 20 Share Email

🚀 Work With Us

Private Coaching

Language Editing

Qualitative Coding

✨ Free Resources

Templates & Tools

Short Courses

Articles & Videos

How To Write A Research Paper

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

F or many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Writing A Dissertation While Working: A How-To Guide

Struggling to balance your dissertation with a full-time job and family? Learn practical strategies to achieve success.

How To Review & Understand Academic Literature Quickly

Learn how to fast-track your literature review by reading with intention and clarity. Dr E and Amy Murdock explain how.

Dissertation Writing Services: Far Worse Than You Think

Thinking about using a dissertation or thesis writing service? You might want to reconsider that move. Here’s what you need to know.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

Can you help me with a full paper template for this Abstract:

Background: Energy and sports drinks have gained popularity among diverse demographic groups, including adolescents, athletes, workers, and college students. While often used interchangeably, these beverages serve distinct purposes, with energy drinks aiming to boost energy and cognitive performance, and sports drinks designed to prevent dehydration and replenish electrolytes and carbohydrates lost during physical exertion.

Objective: To assess the nutritional quality of energy and sports drinks in Egypt.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study assessed the nutrient contents, including energy, sugar, electrolytes, vitamins, and caffeine, of sports and energy drinks available in major supermarkets in Cairo, Alexandria, and Giza, Egypt. Data collection involved photographing all relevant product labels and recording nutritional information. Descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests were employed to analyze and compare the nutritional values of energy and sports drinks.

Results: The study analyzed 38 sports drinks and 42 energy drinks. Sports drinks were significantly more expensive than energy drinks, with higher net content and elevated magnesium, potassium, and vitamin C. Energy drinks contained higher concentrations of caffeine, sugars, and vitamins B2, B3, and B6.

Conclusion: Significant nutritional differences exist between sports and energy drinks, reflecting their intended uses. However, these beverages’ high sugar content and calorie loads raise health concerns. Proper labeling, public awareness, and responsible marketing are essential to guide safe consumption practices in Egypt.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

Research Guide

Chapter 5 sections of a paper.

Now that you have identified your research question, have compiled the data you need, and have a clear argument and roadmap, it is time for you to write. In this Module, I will briefly explain how to develop different sections of your research paper. I devote a different chapter to the empirical section. Please take into account that these are guidelines to follow in the different section, but you need to adapt them to the specific context of your paper.

5.1 The Abstract

The abstract of a research paper contains the most critical aspects of the paper: your research question, the context (country/population/subjects and period) analyzed, the findings, and the main conclusion. You have about 250 characters to attract the attention of the readers. Many times (in fact, most of the time), readers will only read the abstract. You need to “sell” your argument and entice them to continue reading. Thus, abstracts require good and direct writing. Use journalistic style. Go straight to the point.

There are two ways in which an abstract can start:

By introducing what motivates the research question. This is relevant when some context may be needed. When there is ‘something superior’ motivating your project. Use this strategy with care, as you may confuse the reader who may have a hard time understanding your research question.

By introducing your research question. This is the best way to attract the attention of your readers, as they can understand the main objective of the paper from the beginning. When the question is clear and straightforward this is the best method to follow.

Regardless of the path you follow, make sure that the abstract only includes short sentences written in active voice and present tense. Remember: Readers are very impatient. They will only skim the papers. You should make it simple for readers to find all the necessary information.

5.2 The Introduction

The introduction represents the most important section of your research paper. Whereas your title and abstract guide the readers towards the paper, the introduction should convince them to stay and read the rest of it. This section represents your opportunity to state your research question and link it to the bigger issue (why does your research matter?), how will you respond it (your empirical methods and the theory behind), your findings, and your contribution to the literature on that issue.

I reviewed the “Introduction Formulas” guidelines by Keith Head , David Evans and Jessica B. Hoel and compiled their ideas in this document, based on what my I have seen is used in papers in political economy, and development economics.

This is not a set of rules, as papers may differ depending on the methods and specific characteristics of the field, but it can work as a guideline. An important takeaway is that the introduction will be the section that deserves most of the attention in your paper. You can write it first, but you need to go back to it as you make progress in the rest of teh paper. Keith Head puts it excellent by saying that this exercise (going back and forth) is mostly useful to remind you what are you doing in the paper and why.

5.2.1 Outline

What are the sections generally included in well-written introductions? According to the analysis of what different authors suggest, a well-written introduction includes the following sections:

- Hook: Motivation, puzzle. (1-2 paragraphs)

- Research Question: What is the paper doing? (1 paragraph)

- Antecedents: (optional) How your paper is linked to the bigger issue. Theory. (1-2 paragraphs)

- Empirical approach: Method X, country Y, dataset Z. (1-2 paragraphs)

- Detailed results: Don’t make the readers wait. (2-3 paragraphs)

- Mechanisms, robustness and limitations: (optional) Your results are valid and important (1 paragraph)

- Value added: Why is your paper important? How is it contributing to the field? (1-3 paragraphs)

- Roadmap A convention (1 paragraph)

Now, let’s describe the different sections with more detail.

5.2.1.1 1. The Hook

Your first paragraph(s) should attract the attention of the readers, showing them why your research topic is important. Some attributes here are:

- Big issue, specific angle: This is the big problem, here is this aspect of the problem (that your research tackles)

- Big puzzle: There is no single explanation of the problem (you will address that)

- Major policy implemented: Here is the issue and the policy implemented (you will test if if worked)

- Controversial debate: some argue X, others argue Y

5.2.1.2 2. Research Question

After the issue has been introduced, you need to clearly state your research question; tell the reader what does the paper researches. Some words that may work here are:

- I (We) focus on

- This paper asks whether

- In this paper,

- Given the gaps in knoweldge, this paper

- This paper investigates

5.2.1.3 3. Antecedents (Optional section)

I included this section as optional as it is not always included, but it may help to center the paper in the literature on the field.

However, an important warning needs to be placed here. Remember that the introduction is limited and you need to use it to highlight your work and not someone else’s. So, when the section is included, it is important to:

- Avoid discussing paper that are not part of the larger narrative that surrounds your work

- Use it to notice the gaps that exist in the current literature and that your paper is covering

In this section, you may also want to include a description of theoretical framework of your paper and/or a short description of a story example that frames your work.

5.2.1.4 4. Empirical Approach

One of the most important sections of the paper, particularly if you are trying to infer causality. Here, you need to explain how you are going to answer the research question you introduced earlier. This section of the introduction needs to be succint but clear and indicate your methodology, case selection, and the data used.

5.2.1.5 5. Overview of the Results

Let’s be honest. A large proportion of the readers will not go over the whole article. Readers need to understand what you’re doing, how and what did you obtain in the (brief) time they will allocate to read your paper (some eager readers may go back to some sections of the paper). So, you want to introduce your results early on (another reason you may want to go back to the introduction multiple times). Highlight the results that are more interesting and link them to the context.

According to David Evans , some authors prefer to alternate between the introduction of one of the empirical strategies, to those results, and then they introduce another empirical strategy and the results. This strategy may be useful if different empirical methodologies are used.

5.2.1.6 6. Mechanisms, Robustness and Limitations (Optional Section)

If you have some ideas about what drives your results (the mechanisms involved), you may want to indicate that here. Some of the current critiques towards economics (and probably social sciences in general) has been the strong focus on establishing causation, with little regard to the context surrounding this (if you want to hear more, there is this thread from Dani Rodrick ). Agency matters and if the paper can say something about this (sometimes this goes beyond our research), you should indicate it in the introduction.

You may also want to briefly indicate how your results are valid after trying different specifications or sources of data (this is called Robustness checks). But you also want to be honest about the limitations of your research. But here, do not diminish the importance of your project. After you indicate the limitations, finish the paragraph restating the importance of your findings.

5.2.1.7 7. Value Added

A very important section in the introduction, these paragraphs help readers (and reviewers) to show why is your work important. What are the specific contributions of your paper?

This section is different from section 3 in that it points out the detailed additions you are making to the field with your research. Both sections can be connected if that fits your paper, but it is quite important that you keep the focus on the contributions of your paper, even if you discuss some literature connected to it, but always with the focus of showing what your paper adds. References (literature review) should come after in the paper.

5.2.1.8 8. Roadmap

A convention for the papers, this section needs to be kept short and outline the organization of the paper. To make it more useful, you can highlight some details that might be important in certain sections. But you want to keep this section succint (most readers skip this paragraph altogether).

5.2.2 In summary

The introduction of your paper will play a huge role in defining the future of your paper. Do not waste this opportunity and use it as well as your North Star guiding your path throughout the rest of the paper.

5.3 Context (Literature Review)

Do you need a literature review section?

5.4 Conclusion

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research The Research Process

Explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Structuring the Research Paper

Formal research structure.

These are the primary purposes for formal research:

enter the discourse, or conversation, of other writers and scholars in your field

learn how others in your field use primary and secondary resources

find and understand raw data and information

For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research. The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Usually, research papers flow from the general to the specific and back to the general in their organization. The introduction uses a general-to-specific movement in its organization, establishing the thesis and setting the context for the conversation. The methods and results sections are more detailed and specific, providing support for the generalizations made in the introduction. The discussion section moves toward an increasingly more general discussion of the subject, leading to the conclusions and recommendations, which then generalize the conversation again.

Sections of a Formal Structure

The introduction section.

Many students will find that writing a structured introduction gets them started and gives them the focus needed to significantly improve their entire paper.

Introductions usually have three parts:

presentation of the problem statement, the topic, or the research inquiry

purpose and focus of your paper

summary or overview of the writer’s position or arguments

In the first part of the introduction—the presentation of the problem or the research inquiry—state the problem or express it so that the question is implied. Then, sketch the background on the problem and review the literature on it to give your readers a context that shows them how your research inquiry fits into the conversation currently ongoing in your subject area.

In the second part of the introduction, state your purpose and focus. Here, you may even present your actual thesis. Sometimes your purpose statement can take the place of the thesis by letting your reader know your intentions.

The third part of the introduction, the summary or overview of the paper, briefly leads readers through the discussion, forecasting the main ideas and giving readers a blueprint for the paper.

The following example provides a blueprint for a well-organized introduction.

Example of an Introduction

Entrepreneurial Marketing: The Critical Difference

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, John A. Welsh and Jerry F. White remind us that “a small business is not a little big business.” An entrepreneur is not a multinational conglomerate but a profit-seeking individual. To survive, he must have a different outlook and must apply different principles to his endeavors than does the president of a large or even medium-sized corporation. Not only does the scale of small and big businesses differ, but small businesses also suffer from what the Harvard Business Review article calls “resource poverty.” This is a problem and opportunity that requires an entirely different approach to marketing. Where large ad budgets are not necessary or feasible, where expensive ad production squanders limited capital, where every marketing dollar must do the work of two dollars, if not five dollars or even ten, where a person’s company, capital, and material well-being are all on the line—that is, where guerrilla marketing can save the day and secure the bottom line (Levinson, 1984, p. 9).

By reviewing the introductions to research articles in the discipline in which you are writing your research paper, you can get an idea of what is considered the norm for that discipline. Study several of these before you begin your paper so that you know what may be expected. If you are unsure of the kind of introduction your paper needs, ask your professor for more information. The introduction is normally written in present tense.

THE METHODS SECTION

The methods section of your research paper should describe in detail what methodology and special materials if any, you used to think through or perform your research. You should include any materials you used or designed for yourself, such as questionnaires or interview questions, to generate data or information for your research paper. You want to include any methodologies that are specific to your particular field of study, such as lab procedures for a lab experiment or data-gathering instruments for field research. The methods section is usually written in the past tense.

THE RESULTS SECTION

How you present the results of your research depends on what kind of research you did, your subject matter, and your readers’ expectations.

Quantitative information —data that can be measured—can be presented systematically and economically in tables, charts, and graphs. Quantitative information includes quantities and comparisons of sets of data.

Qualitative information , which includes brief descriptions, explanations, or instructions, can also be presented in prose tables. This kind of descriptive or explanatory information, however, is often presented in essay-like prose or even lists.

There are specific conventions for creating tables, charts, and graphs and organizing the information they contain. In general, you should use them only when you are sure they will enlighten your readers rather than confuse them. In the accompanying explanation and discussion, always refer to the graphic by number and explain specifically what you are referring to; you can also provide a caption for the graphic. The rule of thumb for presenting a graphic is first to introduce it by name, show it, and then interpret it. The results section is usually written in the past tense.

THE DISCUSSION SECTION

Your discussion section should generalize what you have learned from your research. One way to generalize is to explain the consequences or meaning of your results and then make your points that support and refer back to the statements you made in your introduction. Your discussion should be organized so that it relates directly to your thesis. You want to avoid introducing new ideas here or discussing tangential issues not directly related to the exploration and discovery of your thesis. The discussion section, along with the introduction, is usually written in the present tense.

THE CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS SECTION

Your conclusion ties your research to your thesis, binding together all the main ideas in your thinking and writing. By presenting the logical outcome of your research and thinking, your conclusion answers your research inquiry for your reader. Your conclusions should relate directly to the ideas presented in your introduction section and should not present any new ideas.

You may be asked to present your recommendations separately in your research assignment. If so, you will want to add some elements to your conclusion section. For example, you may be asked to recommend a course of action, make a prediction, propose a solution to a problem, offer a judgment, or speculate on the implications and consequences of your ideas. The conclusions and recommendations section is usually written in the present tense.

Key Takeaways

- For the formal academic research assignment, consider an organizational pattern typically used for primary academic research.

- The pattern includes the following: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft