Rosenhan (1973) Experiment – ‘On being sane in insane places’

Angel E. Navidad

Philosophy Expert

B.A. Philosophy, Harvard University

Angel Navidad is an undergraduate at Harvard University, concentrating in Philosophy. He will graduate in May of 2025, and thereon pursue graduate study in history, or enter the civil service.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

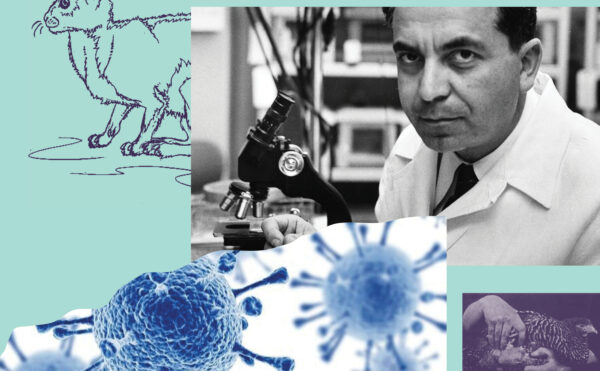

- Between 1969 and 1972, Prof. David Rosenhan, a psychiatrist at Stanford University, sent eight pseudo-patients to 12 psychiatric hospitals without revealing this to the staff. None of the pseudo-patients had any symptoms or history of mental disorders.

- In all 12 instances, pseudo-patients were diagnosed with a mental disorder and hospitalized. In no instance was the misdiagnosis discovered during hospitalization.

- In some of the 12 hospital stays, pseudo-patients observed significant deficits in patient-staff contact.

- In a follow-up study at one hospital, Prof. Rosenhan asked staff to rate patients seeking admission on a 10-point scale, from “highly likely to be a (healthy) pseudo-patient” (1 or 2) to “least likely to be a pseudo-patient.” Staff were aware of the previous study and told one or more pseudo-patients would be sent their way unannounced. Forty-one (21.24%) of 193 patients received a 1 or 2 score. No pseudo-patients were, in fact, sent.

- These findings provided convincing evidence against the accuracy and validity of psychiatric diagnoses.

- The current state of psychiatric diagnoses is still broadly at odds with recent neurological findings, leading to uncertainty regarding their accuracy. Several interventions are proposed or underway to correct this. None counts with widespread support yet.

In the years leading to 1973, professor of law and psychology at Stanford University, Mr. David L. Rosenhan, sought to investigate whether psychiatrists actually managed to tease normal and abnormal psychological states apart. As Prof. Rosenhan put it:

At its heart, the question of whether the sane can be distinguished from the insane (and whether degrees of insanity can be distinguished from each other) is a simple matter: do the salient characteristics that lead to diagnoses reside in the patients themselves or in the environments and contexts in which observers find them? Rosenhan 1973, p. 251.

The recent publication of the APA’s DSM II in 1968 underscored the popular belief among practitioners that psychiatric conditions could be distinguished from each other and from normal psychiatric good health, much like physiological diseases can be distinguished from each other and from good health itself.

In the 1960s, an increasing number of critiques of this belief emerged, arguing that psychiatric diagnoses were not as objective, valid, or substantive as their physiological counterparts, but were rather more like opinions and, therefore, subject to implicit biases even when propounded by competent psychiatrists or psychologists.

Prof. Rosenhan set out to settle the matter empirically. He resolved to have people with no current or past symptoms of serious psychiatric disorders admitted to psychiatric hospitals.

If their lack of abnormal psychiatric traits were always detected, he reasoned, we would have good evidence that psychiatrists were able to tell normal from abnormal psychiatric states. Psychiatric normality, it was presumed, was distinct enough from abnormality to be readily recognized by competent practitioners.

Nine participants, including Prof. Rosenhan, were recruited. All were deemed to have no present or past symptoms of serious psychiatric disorders. Each gained admission to one of nine distinct hospitals.

In eight cases, admittance was gained without the hospital’s staff’s foreknowledge.

In Prof. Rosenhan’s case, the hospital administrator and chief psychologist knew of their hospital’s inclusion in the study. Data from Prof. Rosehan’s stay or stays were not excluded.

Data from one participant were excluded due to a protocol breach (falsification of personal history beyond that of name, occupation, and employment). Between one and four of the remaining eight participants thereafter gained further admission to four other hospitals.

Data from 12 hospital stays, at 12 different hospitals, by eight participants were included in the study. Five of the included participants were male adults; three were female adults. Five worked or were engaged in psychology or psychiatry.

One of the 12 hospitals was privately funded; the rest received public funding. An undisclosed number of hospitals were “old and shabby” or “quite understaffed.”

The 12 hospitals were located in five states in the East and West coasts of the US.

The admittance, stay, and discharge process was as follows —

- Participants set up an appointment at one of the hospitals under a false name, occupation, and employment.

- At the appointment, participants complained they had been hearing unfamiliar, often unclear voices which seemed to come from someone of their own sex and which seemed to say “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud;” participants provided truthful information on all matters other than name, occupation, and employment, with names, occupations and employment information of friends and family changed to fit with the participant’s assumed name, occupation, and employment.

- On admittance, participants stopped simulating any psychiatric symptoms, though there were a few cases of “brief[,] … mild nervousness and anxiety” which “abated rapidly.”

- In psychiatric wards, participants engaged with patients and staff as they would normally with colleagues in everyday life. When asked by staff how they were feeling, participants indicated that they were fine and that they no longer experienced symptoms. They received but did not ingest their prescribed medication, except in one or two instances. They recorded their observations regarding the ward, staff, and patients.

- Participants were discharged when the hospital’s staff responsible for their stay saw fit. A writ of habeas corpus was kept on file for each participant an undisclosed number of days after the study began.

- Between one and four participants repeated this process at four other hospitals.

Two further protocol breaches, which did not result in exclusion, were reported. One participant revealed their occupation in psychology to staff members. Another “attempted a romance with a nurse,” revealed their occupation in psychology to staff members, and provided psychotherapy to fellow patients.

Nursing reports for an undisclosed (“most”) number of the 12 stays were obtained from the hospitals. Coding protocols and training were not reported.

Depersonalization Observations

At four of the 12 hospitals, staff responses to patient-initiated contact were also investigated.

During their stay, four participants approached staff members with a request of the form, “Pardon me, Mr. [or Dr. or Mrs.] X, could you tell me when I will be eligible for grounds privileges?” or “… when I will be presented at the staff meeting?” or “… when I am likely to be discharged?”

No staff member was approached more than once a day. Staff responses were recorded.

Criteria for response classification, recording protocols, and pre-study training were not disclosed.

At six of the 12 hospitals, patients’ daily contact with staff (in minutes), from the initial admission interview to the final discharge meeting, inclusive of both, was measured.

Measurement protocol and pre-study training were not disclosed.

Non-existent Imposter Study

A second study was arranged at a research and teaching hospital in an undisclosed location. Its staff were aware of the first study’s results.

They were informed that one or more persons, previously instructed to simulate at least one symptom of a psychiatric disorder, i.e., a pseudo-patient, would attempt to gain admission within the following three months.

Staff were asked to rate each patient seeking admission on a ten-point scale, from most likely to be a pseudo-patient (1 or 2 on the scale) to least likely. No participants were, in fact, sent to the hospital. Scores were obtained for 193 patients.

No patients were independently evaluated by Prof. Rosenhan or affiliated researchers. No scoring protocol nor pre-study training was reported.

In eleven instances, participants were admitted on a diagnosis of schizophrenia and discharged with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in remission.

In one instance, a participant was admitted on a diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis; their discharge diagnosis was not reported. Stays ranged from 7 to 52 days, with a mean of 19 days. Standard deviation was not disclosed.

Nursing reports “uniformly indicate[d] that the [participants] were “friendly,” “cooperative,” and “exhibited no abnormal indications.” Coding results and statistical significance were not reported.

Participants’ visitors “could detect no serious behavioral consequences [of hospitalization in participants].” No information on data collection from said visitors, nor statistical analyses on these data, were reported.

The errant diagnosis on admission, Prof. Rosenhan noted, could simply be attributed to physicians’ strong bias towards type II errors. As he put it:

The reasons [for this strong bias] are not hard to find: it is clearly [less] dangerous to misdiagnose illness than health. Better to err on the side of caution, to suspect illness even among the healthy. Rosenhan 1973, p. 252

Errant diagnoses after admission, once participants had dropped all pretense of psychiatric disturbance, were more surprising and troubling to Prof. Rosenhan.

It seemed that once diagnosed with an aberrant psychiatric trait, participants were unable to escape the diagnosis, despite their having dropped the farce immediately upon admission.

It was presumed that a competent practitioner, upon being well-acquainted with participants, would eventually identify the initial diagnosis as a type II error and subsequently correct it. No such correction took place in any of the 12 hospital stays.

The admission diagnoses seemed, in Prof. Rosenhan’s words, “so powerful that many of the [participants’] normal behaviors were overlooked entirely or profoundly misinterpreted.”

Prof. Rosenhan offered the following explanation for this surprising result. Persons not diagnosed with a mental illness, nonetheless, at times, exhibit “aberrant” behavior, like pacing around or frequently writing. Without a psychopathic diagnosis, these behaviors are attributed to something other than psychopathy, like being bored or being a writer.

But in the presence of such a diagnosis, these behaviors are more often attributed to psychopathy, as they were in two instances in the study than not. This attribution, in turn, only reinforces the diagnosis, thereby fixing any type II errors in place.

The fact that such behaviors are often attributed to psychopathies in diagnosed patients, Prof. Rosenhan argued, points more to the “enormous overlap in behaviors of the sane and the insane” than to the competence of psychiatrists, psychologists, or nurses.

On initiating contact with staff members, participants were overwhelmingly not paid any attention by psychiatrists, nurses, or attendants at four of the hospitals. Inter-hospital differences were not deemed significant and were not reported. Statistical differences and significance were not reported.

Six participants, totaling 129 days of hospitalization, measured their daily contact with staff. Daily contact with psychiatrists, psychologists, residents, and physicians ranged from 3.9 to 25.1 minutes, with a mean of 6.8 minutes. Disaggregated data, contact time with other staff, statistical differences, statistical significance, and standard deviation were not reported.

Contact, Prof. Rosenhan notes, indicates “concern and individuation,” its lack, “avoidance and depersonalization.” Staff’s overwhelming avoidance of patients, Prof.

Table 1. Self-initiated contact by participants with psychiatrists, nurses, and attendants. Adapted from Table 1 of the 1973 Rosenhan study, p. 255. Copyright (c) 1973 AAAS.

Rosenhan notes resulted in an “overwhelming sense of powerlessness which invades the individual as he is continually exposed to the depersonalization of the psychiatric hospital.”

The import of this practice, and the powerlessness it elicited, Prof. Rosenhan argued, could be readily inferred.

[H]ow many patients might be “sane” outside the psychiatric hospital but seem insane in it_—not because craziness resides in them, as it were, but because they are responding to a bizarre setting … ? — Rosenhan 1973, p. 257

Of the 193 scores obtained, 41 patients were judged highly likely to have been a pseudo-patient by at least one staff member, 23 by at least one psychiatrist, and 19 by one psychiatrist and at least one other staff member. No pseudo-patients were sent by Prof. Rosenhan or affiliated researchers.

Of the 41 patients judged highly likely to have been pseudo-patients —

- Either they did not, in fact, have any abnormal psychiatric symptoms and were correctly judged pseudo-patients by the staff;

- Or they did, in fact, have abnormal psychiatric symptoms (as presumed by the fact that they wished to be admitted), in which case the staff misdiagnosed them as pseudo-patients and thereby made a type I error in seeking to avoid type II errors.

In either case, Prof. Rosenhan pointed out the results indicated “that the tendency to designate sane people as insane can be reversed when the stakes (in this case, prestige and diagnostic acumen) are high.”

But it is notable that, in the second case, the price for avoiding type II errors might just be a higher type I error rate.

It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals. The hospital itself imposes a special environment in which the meanings of behaviour can easily be misunderstood. Rosenhan 1973, p. 257

Both practitioners and patients, the study reveals, seem caught in Catch-22s. Out of an excess of caution, psychiatrists and psychologists strongly tend towards type II errors on admission. But once said error is made, there’s a slim chance it will be caught during in-patient treatment.

On the other hand, should practitioners try to avoid type II errors from sticking to patients, they run the risk of equally damaging type I errors. On the other hand, patients, once admitted, are likely to develop psychopathies, whether they truly had any on admission or not, given the bizarre setting they are thrust into on admittance.

But should they seek to avoid the setting — the psychiatric hospital — they run the risk of an untreated mental illness getting worse, in the case they truly suffered one, to begin with.

A way out for practitioners and patients is not immediately clear to Prof. Rosenhan. Two promising directions he noted were —

- The avoidance of psychiatric diagnoses of the form encouraged by the DSM II in favor of diagnosing patients with “specific problems and behaviors” so as to provide treatment outside of psychiatric hospitals and to keep any diagnostic label from “sticking” to a patient;

- Increasing “the sensitivity of mental health workers and researchers to the Catch-22 position of psychiatric patients,” for e.g., by having them read pertinent literature.

Other Conclusions

A good number of the study’s shortcomings should give us pause when drawing conclusions. Sampling, randomization, control, blinding, and statistical analysis methods were largely unreported and so likely not to have been up to present-day standards.

Participant training was not reported and so likely not undertaken before the study. No data on participants’ visitors and their evaluations were reported.

Study flaws aside, the observed effects were large enough to likely be clinically, and easily statistically, significant —

- All 12 hospitalizations resulted in type II errors both on admission and discharge;

- 2.94% of the 1,468 recorded participant-initiated interactions with psychiatric staff resulted in verbal engagement with the participant;

- 9.84% of the 193 patients scored at a research and teaching hospital were deemed very likely to have had no psychopathic traits on admission by both a psychiatrist and at least one other staff member.

The findings pointed to an unacceptable preponderance and persistence of type II errors by competent psychiatric staff and to the danger of psychiatric harm to patients posed by then-current psychiatric practices.

Critical Evaluation

Was the sample representative.

Field experiments have the major advantage of being conducted in a real environment and this gives the research high ecological validity. However, it is not possible to have as many controls in place as would be possible in a laboratory experiment.

Participant observation allows the collection of highly detailed data without the problem of demand characteristics. As the hospitals did not know of the existence of the pseudopatients, there is no possibility that the staff could have changed their behavior because they knew they were being observed.

However, this does raise serious ethical issues (see below) and there is also the possibility that the presence of the pseudopatient would change the environment in which they are observing.

Strictly speaking, the sample is the twelve hospitals that were studied. Rosenhan ensured that this included a range of old and new institutions as well as those with different sources of funding.

The results revealed little differences between the hospitals. This suggests that it is probably reasonable to generalize from this sample and suggest that the same results would be found in other hospitals.

Prof. Rosenhan’s 1973 paper does not detail —

- How his sample size was determined, nor how his sample was selected;

- The study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria;

- How past or present serious psychiatric symptoms were diagnosed, nor by whom;

- Whether past or present mild to moderate psychiatric symptoms were diagnosed, nor by whom;

- How hospitals were selected;

- How participants were matched with false names, occupations, and employment information;

- How participants were matched with hospitals.

What type of data was collected in this study?

There is a huge variety of data reported in this study, ranging from quantitative data detailing how many days each pseudopatient spent in the hospital and how many times pseudopatients were ignored by staff to qualitative descriptions of the experiences of the pseudopatients.

One of the strengths of this study could be seen as the wealth of data that is reported and there is no doubt that the conclusions reached by Rosenhan are well illustrated by the qualitative data that he has included.

Was the study ethical?

Strictly speaking, no. The staff were deceived as they did not know that they were being observed and you need to consider how they might have felt when they discovered the research had taken place.

Was the study justified? This is more difficult as there is certainly no other way that the study could have been conducted and you need to consider whether the results justified the deception. This is discussed later under the heading of usefulness.

What does the study tell us about individual/situational explanations of behavior?

The study suggests that once the patients were labeled, the label stuck. Everything they did or said was interpreted as typical of a schizophrenic (or manic-depressive) patient. This means that the situation that the pseudopatients were in had a powerful impact on the way that they were judged.

The hospital staff was not able to perceive the pseudopatients in isolation from their label and the fact that they were in a psychiatric hospital, and this raises serious doubts about the reliability and validity of the psychiatric diagnosis.

What does the study tell us about reinforcement and social control?

The implications of the study are that patients in psychiatric hospitals are ‘conditioned’ to behave in certain ways by the environments that they find themselves in.

Their behavior is shaped by the environment (nurses assume that signs of boredom are signs of anxiety, for example) and if the environment does not allow them to display ‘normal’ behavior, it will be difficult for them to be seen as normal.

Labeling is a powerful form of social control. Once a label has been applied to an individual, everything they do or say will be interpreted in the light of this label.

Rosenhan describes pseudopatients going to flush their medication down the toilet and finding pills already there. This would suggest that so long as the patients were not causing anyone any trouble, very few checks were made.

Was the study useful?

The study was certainly useful in highlighting the ways in which hospital staff interact with patients. There are many suggestions for improved hospital care/staff training that could be made after reading this study.

However, it is possible to question some of Rosenhan’s conclusions. If you went to the doctor falsely complaining of severe pains in the region of your appendix and the doctor admitted you to the hospital, you could hardly blame the doctor for making a faulty diagnosis.

Isn’t it better for psychiatrists to err on the side of caution and admit someone who is not really mentally ill than to send away someone who might be genuinely suffering?

This does not entirely excuse the length of time that some pseudopatients spent in the hospital acting perfectly normally, but it does go some way to supporting the actions of those making the initial diagnosis.

Outlook of Diagnostic Accuracy

Psychiatric diagnoses continue to be made as they were at the time of Prof. Rosenhan’s study — largely on the basis of inferences drawn from patient self-reports and practitioners’ observations of patient behavior and largely on the basis of criteria set by the APA’s DSM. This suggests two sources of diagnostic problems in psychiatry —

- the evidence used to reach a diagnosis, and

- the criteria by which said evidence is evaluated in reaching a diagnosis.

The evidence available to psychiatrists and psychologists in diagnosing mental disorders has long been much sparser than that available to other physicians.

There have been advances in the etiology of mental disorders — the relevant MeSH term now counts over 370,000 articles in PubMed, 4.00% of which are RCTs, meta-analyses, or systematic reviews. This growing corpus has yet to yield diagnostic tests, though.

In 2012, a group of three psychiatrists, led by Prof. Shitij Kapur of King’s College London, argued that a number of reasons were responsible for this lag, including widespread methodological shortcomings and the DSM’s classification itself.

On that note, the DSM has left much to desire. As Mr. Thomas Insel, former director of the NIMH, put it —

Unlike our definitions of ischemic heart disease, lymphoma, or AIDS, the DSM diagnoses are based on a consensus about clusters of clinical symptoms, not any objective laboratory measure. Insel 2013, second para.

Since its first publication in 1958, the DSM has reached a classification of mental disorders without data on their biological underpinnings.

Its nosology is increasingly at odds with aetiological research, which increasingly suggests that mental disorders are rather gradual deviations from typical brain functions.

This, in turn, suggests that mental disorders should be classified as points or areas on spectra rather than the neat categories propounded by the DSM. One effort at building such a nosology was begun by the NIMH in 2010.

The project dubbed the RDoC, is still confined to research, and is not ready for clinical application.

The myriad problems in psychiatric research and practice preclude any consensus on the accuracy of psychiatric diagnoses and are likely to do so until they are resolved.

The field has not converged on a corrective program, though there exist a number of such programs competing for widespread support.

What did the Rosenhan study suggest in 1973?

The Rosenhan study in 1973 suggested that psychiatric diagnoses are often subjective and unreliable. Rosenhan and his associates feigned hallucinations to get admitted to mental hospitals but acted normally afterward.

Despite this, they were held for significant periods and treated as if they were genuinely mentally ill. The study highlighted issues with the validity of psychiatric diagnosis and the stigma attached to mental illness.

What did the classic study by Rosenhan reveal about the power of labels that are applied to individuals?

The classic study by Rosenhan showed the influential effect of labels on individuals, specifically psychiatric labels. By pretending to have hallucinations, mentally healthy participants gained admission to psychiatric hospitals.

The study demonstrated that once labeled as mentally ill, their behaviors were consistently interpreted in that context, even when they stopped simulating symptoms.

Adam, D. (2013). On the spectrum. Nature, 496(7446), 416.

Insel, T. .R. (2013, 29th April). Transforming Diagnosis. [Weblog]. Retrieved 4 November 2020, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

Kapur, S., Phillips, A. G., & Insel, T. R. (2012). Why has it taken so long for biological psychiatry to develop clinical tests and what to do about it?. Molecular psychiatry, 17 (12), 1174-1179.

Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179( 4070), 250-258.

Sharp, C., Fowler, J. C., Salas, R., Nielsen, D., Allen, J., Oldham, J., Kosten, T., Mathew, S., Madan, A., Frueh, B. C., & Fonagy, P. (2016). Operationalizing NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) in naturalistic clinical settings. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 80 (3), 187–212.

Further Information

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179(4070), 250-258.

- Spitzer, R. L. (1975). On pseudoscience in science, logic in remission, and psychiatric diagnosis: A critique of Rosenhan”s” On being sane in insane places.”

- David Rosenhan’s Pseudo-Patient Study

- Distillations Podcast

Distillations podcast

The fraud that transformed psychiatry.

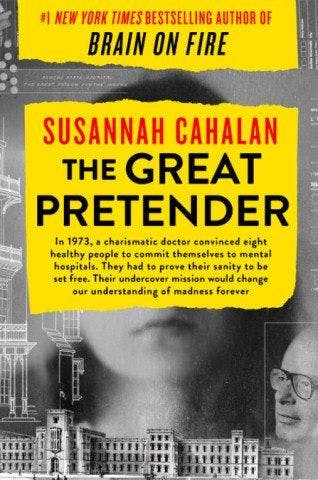

Psychology professor David Rosenhan made waves with his “On Being Sane in Insane Places” study, but decades later its legitimacy was questioned.

In 1973 a bombshell study appeared in the premier scientific journal Science . It was called “On Being Sane in Insane Places.” Its author, a Stanford psychology professor named David Rosenhan, claimed that by faking their way into psychiatric hospitals, he and eight other pseudo-patients had proven that psychiatrists were unable to diagnose mental illness accurately.

Psychiatrists panicked, and, as a result, re-wrote what’s known as “psychiatry’s bible”—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM. The study and the subsequent overhaul of the DSM changed the field forever. So it was a surprise when, decades later, a journalist reopened Rosenhan’s files and discovered that the study was full of inconsistencies and even blatant fraud. So should we throw out everything it revealed? Or can something based on a lie still contain any truths?

Host: Alexis Pedrick Senior Producer: Mariel Carr Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer “Color Theme” composed by Jonathan Pfeffer . Additional music by Blue Dot Sessions

Resource List

Archive audio of Dr. David Rosenhan in conversation with Harvey Tiler of Psychology Today magazine and NPR’s Carol Duchen at the American Psychological Association convention in fall 1982.

The Great Pretender: The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness , by Susannah Cahalan

Madness and Medicine (1977)

Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness , by Andrew Scull

Titicut Follies (1967)

Alexis Pedrick: In 1973, a bombshell study appeared in the premier scientific journal, Science . It was called, “On Being Sane in Insane Places.”

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: Dr. Rosenhan, you did a study and in the study you got yourself committed to an institution, a mental institution. How did you get them to believe that you were, you were mentally ill or that you had an emotional problem? What it really amounted to was faking a set of symptoms. Did the doctors ever catch on? Never.

Alexis Pedrick: Does that sound as wild to you as it did to me? Let’s go back to the beginning. In 1969, at Swarthmore College, just outside of Philadelphia, there was a beloved psychology professor named David Rosenhan. He was known for his tweed jackets with elbow patches, his large bald head, and his deep authoritative lecture voice. This is Susannah Cahalan, the author of a book about him called The Great Pretender .

Susannah Cahalan: Rosenhan, you know, he was this raconteur, he was funny, and he had this great voice, and he could command a room, and people really loved him, really gravitated towards him.

Alexis Pedrick: But one day, a group of undergraduate students visited him in his smoky basement lab to complain. They were taking his abnormal psychology seminar, and it was too abstract. How would they ever really understand mental illness without any real world encounters?

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation This whole thing began when I was planning to bring you in an undergraduate seminar in a hospital to give you some sense of what schizophrenics are really like and what patients are really like. Let’s not talk about them, let’s not go visit them, let’s go live with them for a while.

Alexis Pedrick: That was David Rosenhan, speaking to an NPR reporter on stage at an American Psychological Association convention in 1982. And yes, his idea was that the students would get themselves admitted to psychiatric hospitals, secretly, by pretending to have a mental illness. But first, Rosenhan had to prepare his students. He got them acquainted with the work of academics and journalists who had gone undercover in psychiatric hospitals, and there was a common theme to their reporting. Probably the nicest way to say it is that they had an unfavorable view of mental institutions.

You see, psychiatry had gone through a boom time in the post-World War II years. Freudian psychoanalysis was all the rage. Mental asylums reached their peak numbers, and the first anti-psychotic drug, Thorazine, was hailed as a rare breakthrough.

Madness and Medicine: Thorazine, the first of the major tranquilizers, was given to several million patients within months of its introduction. The drugs couldn’t have come at a better time. Patient populations were rising and the drugs promised to slow that growth.

Alexis Pedrick: But by the 1960s, the backlash had arrived. This is sociologist Andrew Scull, the author of several books about psychiatry.

Andrew Scull: There’d arisen a growing skepticism among intellectuals about psychiatry, what now we tend to call anti psychiatry.

Alexis Pedrick: In 1961, a Hungarian American psychoanalyst named Thomas Szasz made waves for criticizing his own profession.

Andrew Scull: And he wrote a book called The Myth of Mental Illness , in which he said, you know, mental illness is a myth. This is a creation of the profession.

Titicut Follies: You, you looked at me and you tell me I’m a schizophrenic paranoia. I, how, just how do you know? Because, because I speak well, because, uh, because I, I stand up for what I, what I think. Because you get, because you get the psychological testings.

Alexis Pedrick: And it wasn’t just books. In 1967, Frederick Wiseman’s film, Titicut Follies , documented life at a hospital for the, quote, criminally insane, and provided evidence for Thomas Szasz’s arguments against forcible psychiatric treatment.

Titicut Follies: May I ask just why I need this help that I, uh, that you are literally…

Alexis Pedrick: The growing anti psychiatry movement went hand in hand with the civil rights movement, and was embraced by the growing counterculture of the decade. People started asking, was labeling someone as mentally ill just a way of singling out difference, or of calling out nonconformity?

Andrew Scull: And then there was, within my own profession, and my colleague briefly, while I was at the University of Pennsylvania, Irving Goffman, and Goffman had written a book in 1961 called Asylums , in which he compared mental hospitals to concentration camps and prisons.And he said that the mental hospital was something that dehumanized people, that destroyed them, that damaged their ability to act as autonomous people and, in effect, sort of manufactured madness.

Alexis Pedrick: Everything Rosenhan assigned to his students describes psychiatric hospitals as authoritarian, degrading, and illness maintaining. So it’s pretty clear what he expected them to find when they got themselves admitted.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: But before I did that, it seemed reasonable that I should do it first.

Alexis Pedrick: That’s right, David Rosenhan got himself covertly admitted to a psychiatric hospital. And what followed in the wake was, to use a colloquialism, completely bananas. His undercover mission grew. It became a scientific study that the prestigious journal Science published in 1973. And it changed psychiatry forever.

From the Science History Institute, I’m Alexis Patrick, and this is Distillations.

Chapter One. On Being Sane in Insane Places.

So how did David Rosenhan get himself admitted?

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: I went down the first time of my wife, which was a harrowing. There was my wife walking that. What I call that narrow line between an experiment and reality. Here she was, taking her husband and committing him.

Alexis Pedrick: She must have had a lot of faith, because it was a big thing he was asking her to do. It was a big thing he was asking himself to do, which might have been why he was so nervous leading up to it. Rosenhan was potentially putting himself into a situation he might not have been able to get out of. Still, he persevered, faking his symptoms.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: The symptoms went something like this, I’m hearing voices, the voices are saying, dull, empty, thud.

Alexis Pedrick: Rosenhan was diagnosed with schizophrenia and admitted to the hospital. He spent nine days there, enduring what he described as a dehumanizing experience.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: The food was awful, but after five, six days, you didn’t notice that either. It wasn’t really bad physically. And people who judge a hospital on the basis of its physical characteristics are making some enormous mistakes. No hospital is an ideal place to live.

Alexis Pedrick: Rosenhan couldn’t sleep because of the constant noise. Yelling, fire alarms, attendants cursing at patients to get out of bed. And being an undercover psychiatric patient had its own unique stresses. On one hand, he was constantly worried about being found out. On the other, being seen as a real patient was a traumatic experience.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: Sometime what struck me the most was very invisibility. You’re standing there as a patient, perhaps as being brutalized by a staff member. Nobody, nobody stops because you’re looking. Because obviously you’re crazy, you’re in the way. But then down the hall comes a nurse or another staff member. Suddenly, everything stops. I’m so used to being visible. All of us are. I’m so used to having some power that I think one of the most distressing is just being invisible.

Alexis Pedrick: But if you thought Rosenhan was invisible because he spent all of his time acting like a mentally ill patient. You’d be wrong. As soon as he was inside the hospital, he began to behave normally because, and this is important, he didn’t want to just find out what psychiatric hospitals and patients were really like. He was also interested in that Thomas Szasz that theory. That mental illness was a myth, a creation of the profession. He wanted to test whether psychiatrists could actually tell who had mental illness and who didn’t. In his words, could they tell the sane from the insane? And it might seem like a strange question now, but in the context of what was going on in psychiatry at the time, it made sense. The field was at war with itself.

This is Andrew Scull again.

Andrew Scull: American culture after the war became saturated with psychoanalytic ideas. Social scientists in the university embraced them. Historians embraced them. Hollywood embraced them. Broadway embraced them. Novelists.

Alexis Pedrick: Freud brought a brand of psychiatry called psychoanalysis to the U.S. and you know the stereotype. A psychiatrist sitting in a chair, smoking a pipe, asking a patient who’s lying on a couch about her dreams.

Andrew Scull: The Freudians saw symptoms as the tip of the iceberg, the thing you needed to get behind. They were interested in the psychodynamics of this particular patient in front of them and putting a label like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder on them for them was just a waste of time.

Alexis Pedrick: Even though the Freudian psychiatrists were small in number their influence was growing.

Andrew Scull: They can treat 2, 000 patients at a point where there are about 400 ,000 patients in America’s mental hospitals just to give you a comparison

Alexis Pedrick: And over time, they came to dominate medical schools and psychiatry departments across the country.

Andrew Scull: So by 1960, virtually all of them, other than Washington U in St. Louis, were led by a psychoanalyst or somebody sympathetic to psychoanalysis.

Alexis Pedrick: Psychiatry was grappling with how important diagnosis was, in large part because they had a new tool. Before psychiatric drugs came along in the 1950s, specific diagnoses weren’t super important in asylums, because there was limited ways to treat any condition.Sure, they had to keep track of their patients and divide them up into groups, but categories could be vague. When Thorazine came out in 1954, diagnosis started having more ramifications. Thorazine was good for schizophrenia, whereas Lithium was good for bipolar disorder, so you wanted to get the diagnosis right.

Although that right diagnosis didn’t happen for David Rosenhan. Even though he said no if anyone asked him if he was experiencing symptoms or hearing voices, his diagnosis never changed. Score one for Thomas Szasz. When Rosenhan returned to campus, his colleagues and students noticed a change in him. He seemed humble, worn out, older. He decided he couldn’t send any undergraduate students. students in his wake. It was too traumatic. The experiment was done. But then, the very next month, in March of 1969, a chance encounter changed everything, and David Rosenhan realized he had a real scientific experiment on his hands, and he didn’t need undergraduate students to do it.

Here he is describing the gist of the study in an interview with NPR in 1982.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: Between 1969 and 1970, a group of colleagues and I gained admission to psychiatric hospitals by simulating, by faking a single symptom, which was that we said that we heard voices, and the voices said, empty, dull, thud. And our expectation was that they would catch us right at the door.

Alexis Pedrick: But they didn’t catch a single pseudopatient as the anonymous participants came to be known.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: All told were nine people who’ve been into 19 hospitals on 22 occasions. And the hospitals are located all over the United States, mainly on the east and west coast. Some of us have been in once, some of us have been in two or three times. Some of us are graduate students. Uh, there’s a pediatrician, a painter, a psychiatrist, a school teacher, a couple of psychologists. That pretty much covers us.

Alexis Pedrick: The Science article said that all but one pseudopatient was diagnosed with schizophrenia. All because of that same single phrase: dull, empty, thud. They were never unveiled as being imposters.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: What were some of the other conclusions that you drew from the study that you did? In a psychiatric hospital, mental health personnel, psychiatrists and nurses, attendants, cannot tell sanity from insanity.

Alexis Pedrick: Rosenhan assured his interviewer that all nine pseudopatients were eventually discharged, all but one with the revised diagnosis, schizophrenia in remission.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: Now, in remission doesn’t mean quite the same thing as sane.

Alexis Pedrick: Perhaps the most damning part of the study didn’t involve any pseudopatients at all. At one point during the experiment, David Rosenhan described an arrangement he had with a doctor at a prestigious hospital. The hospital was aware that Rosenhan would be sending a pseudopatient, but they didn’t know when. During a three month period, 193 new patients entered the hospital. Psychiatrists there labeled 23 of them as likely pseudopatients. But in fact, Rosenhan never sent anyone. It was clear to him that we react to what we are primed to see. In a New York Times interview, David Rosenhan said, quote, “Any diagnostic process that yields so readily to massive errors of this sort cannot be a very reliable one.”

The publishing of Rosenhan’s study On Being Sane in Insane Places set off a chain of events That changed psychiatry forever. It was an immediate stab to the profession’s credibility. Psychiatrists don’t know what they’re doing. They’re institutionalizing, sane people. All of this fed into an existing fear about psychiatric diagnosis.

Andrew Scull: There was growing anxiety in a few quarters about the fact that psychiatrists seem unable to agree more than about 50% of the time. The council of the American Psychiatric Association called a frantic emergency meeting within a month of this study appearing and said, oh my God, we’ve got to fix this problem with diagnosis. We’ve got to create a new system that allows psychiatrists in Walla Walla, in Saskatchewan, and in Florida and New York, confronted by the same patient, give that patient the same diagnosis, because otherwise we look like fools.

Alexis Pedrick: Psychiatric asylums, which were already in decline, began closing at an even more rapid clip.

Susannah Cahalan: But it was the kind of essential part of the system that started to shut down after the Rosenhan study.

Alexis Pedrick: The study went on to be one of the most widely cited psychology studies ever. It still appears in textbooks. So it came as a surprise nearly 50 years after its publishing, when author Susannah Cahalan discovered that the study was not at all what it was supposed to be.

Susannah Cahalan: You knew something was off? Upon looking at the archives, but you didn’t know to the extent, it took years of, of work to uncover it.

Andrew Scull: What was remarkable was if that information surfaced at the time, it would have completely discredited the study. It’s what I regard as one of the biggest social scientific frauds of the 20th century.

Alexis Pedrick: In a way, the study itself was meant to be a fraud. It was based on people faking their way into psychiatric hospitals. But this is not the fraud we’re talking about. Susannah Cahalan discovered a different, bigger fraud. So, what was it? And does it mean that everything the study stood for and set out to do should be thrown out? Or can something based on a lie still reveal any truths?

Chapter Two. The Other Pseudopatients.

When Susannah Cahalan decided to write a book about Rosenhan, she was surprised by how such a widely cited study was still full of such mystery. David Rosenhan had ultimately gotten eight pseudopatients to join the study, but decades later, no one had managed to unmask them.

Susannah Cahalan: And I thought, who are these volunteers? Who were these eight people? Why would they do this? None of them were named. And the fact that no one had talked about it, and no one had been, except for the author, David Rosenhan, that was intriguing and exciting, and it felt like something buried, but I had no idea how buried at the time.

Alexis Pedrick: That chance encounter David had that changed everything happened at a lecture he was giving in Santa Monica. According to his notes, he was speaking about his hospital stay to a married couple who were both retired psychologists, and they were so intrigued that they decided to try it for themselves.

They were pseudopatients 2 and 3, and they both got admitted to the hospital, were diagnosed with schizophrenia, and had similar dehumanizing and traumatic experiences as David Rosenhan. Despite this, Rosenhan’s notes say that two more anonymous volunteers went and got themselves admitted to two more hospitals, resulting in similar experiences and diagnoses.

By 1970, the data was pouring in. And even though Rosenhan hadn’t published anything yet, word was getting around that this could be a major contribution to the field. Unlike those undercover accounts Rosenhan had his Swarthmore students read, he now had within his grasp an experiment that was solid, evidence backed, and most importantly, scientific.

It was so promising that Stanford recruited him to teach in their psychology department, and it was there that he met the first pseudopatient that Susannah Cahalan managed to unmask.

Bill Underwood: My name is Bill Underwood. I am a retired computer engineer, actually. But prior to being in engineering, I was a psychology professor. And before that, I was a graduate student in psychology at Stanford with David Rosenhan as my supervising professor.

Susannah Cahalan: And at the time Bill took part in it, he was part of a seminar. And it was very clear to Bill that David was trying to recruit people in the seminar to take part in the study.

Bill Underwood: David was a very charming man. He was very charismatic. When you were interacting with him, he was really focused on you. You felt like you were sort of the center of the universe at that point. It was easy to get involved in the things that he was interested in, and so everyone basically said, oh yes, that sounds like a good thing to do, but in the end, I think only two of us actually did the pseudo patient experience out of the seminar.

Alexis Pedrick: Whatever reservations Rosenhan had before about putting students through such a traumatic experience were now pushed aside. These students were older, at least, graduate students, but that also meant that some had more at stake. When Bill Underwood left to fake his way into a mental hospital in San Francisco, he left his wife home with his two young children.

Bill Underwood: I don’t think she was thrilled about it, but she sort of, I guess, understood that it, that it could potentially be an interesting and valuable thing to do. But, um, I, I think it would be fair to say that she was not enthusiastic about it.

Alexis Pedrick: In his notes, Rosenhan describes a Bill Dixon.

Bill Underwood: Bill Dixon. Yeah, I was gonna use Nixon, since I was not fond of our president at the time, and so I thought the idea of portraying Nixon as a psychiatric patient, that had a certain amount of appeal for me, but I was sufficiently paranoid about being found out that I thought, no, I’m not gonna do anything that obvious, so I changed it to Dixon.

Alexis Pedrick: Rosenhan wrote that he was a red bearded Texan who was prodigiously normal. If anyone wasn’t going to fool psychiatrists at the gate, it would probably be Bill.

Bill Underwood: I felt like I was going to be found out. I was extremely nervous. I thought, you know, there are all these people that have gone in and succeeded at this, and I’m going to be the first failure.

Alexis Pedrick: But he did get in, again, based on the same symptoms.

Bill Underwood: Empty, hollow, thud, not, like, complete sentences or anything of that sort.

Alexis Pedrick: He was interviewed again at the hospital where the psychiatrist pressed him to admit that he was gay. I know Freud at one time had a hypothesis that paranoia was linked to homosexuality. It may be that this was sort of a leftover of that general idea among Freudian analysts.

Alexis Pedrick: Psychiatric interviews were not the only thing pseudopatients had to navigate. Rosenhan knew that if they were diagnosed with schizophrenia, they would surely be given Thorazine, which was no minor worry. After 15 years on the market, severe side effects were emerging. Things like Tardive Dyskinesia, an irreversible neurological syndrome that causes repetitive involuntary movements. Not to mention, it knocked people out and into submission, which meant it was often used more as a control measure than a therapeutic tool. The only thing Rosenhan could do was show his volunteers how to make it look like they were taking it, but really spit it out.

Bill Underwood: We had a little practice with, you aspirins and stuff where you would put it in your mouth, put it under your tongue. Swallow some water, wander around, spit it out, because you don’t really want to be taking those drugs.

Alexis Pedrick: But on Bill’s first day in the hospital, they brought the pills around at lunchtime, and he couldn’t leave the room. The doors were locked.

Bill Underwood: And so, I thought, well, I’ll just leave it under my tongue, and then after lunch, I’ll go spit it out. But the coating melted, and that stuff kind of burns. And so, it was burning the area under my tongue, and so I thought, you know, this is crazy. I’m just going to go ahead and swallow it. I’ve went out to the general ward area and promptly fell asleep. I mean, I was out and Marian, my wife, came by to see me. And I mean, I was just barely conscious. Marian was very upset, of course, because she didn’t know what was going on, and I just kept asking her to leave because I just really wanted to sleep.

Alexis Pedrick: After that first day, he was able to spit out the Thorazine and flush it down the toilet.

Bill Underwood: And one time, I remember I went in there, it’s been about three minutes since I had taken the pills, went into the toilet to get rid of my, uh, Thorazine, and there were already some pills in the bottom of the toilet when I got there. So I was clearly not the only one who was following that procedure.

Alexis Pedrick: This was valuable information about how drugs were used in hospitals, and David Rosenhan would go on to talk about this experience of Bill’s.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: We were not alone in spitting out our medication. We’d get to the bathroom and find the bottom of the toilet bowl lying with pink and yellow little things from all the patients we’ve gotten there before us. We got very little treatment except drugs, medications, and in that sense, drugs, however good they may be, have done a real disservice to patients and to staff because there you are in the hospital and the nurse and the physician are feeding you medications and they feel that the medications are getting you better. And consequently, there’s nothing else that needs to be done.

Alexis Pedrick: Like David, Bill felt ignored by the staff, invisible.

Bill Underwood: We didn’t get a lot of attention from the ward attendants. I remember one day early in my time there, I went up to one of the ward attendants to point out that there was something going on with a couple of guys over at the side of the yard. And he just turned his back and walked away from me. I thought, geez, this is not the kind of interaction I am used to having with people. Not the sort of reaction I would expect.

Alexis Pedrick: It was an unpleasant feeling, but the lack of attention was also potentially dangerous.

Bill Underwood: Early one morning before breakfast, one of the nurses woke me up. And said, uh, Mr. Dixon, uh, wake up, you have diabetes. You need to go to this medical facility in the hospital here. And so I thought, good lord, you know, I had no idea I was diabetic.

Alexis Pedrick: But it turned out that the nurse had confused him with another patient with the same name.

Bill Underwood: And it turns out it was the other Dixon. I was 20 years younger than him. I had red hair and a beard. He was clean shaven and had black hair. But, you know, other than that, we looked just alike. But anyway, it made me feel like they were not paying very close attention. So, there were people who were paying attention to what I was doing, but it was not the staff people. And so, to me, that, that is a statement about the extent to which the staff were really attending to what I was doing. Or maybe they were just saying, okay, he’s not causing trouble. I need to focus on these other people. Whatever the reason, there were a lot of people who were paying more attention to me than the staff. And those people were my fellow patients.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: Did patients suspect that you weren’t another patient with psychological problems? Man, they sure did. Nobody ever spotted it except the patients. The patients would walk right up to me and say, ‘You are not, you’re not a patient. You’re a college professor or you’re a journalist.’ One of the clues they had is that the moment we got into the hospital, we would constantly write. I had a big yellow pad and everything that was going on, I would grab my pen, I’d write it down. We wrote reams of stuff. The patients would see us writing and immediately infer, well, he’s observing and he is writing. He must be a journalist or a professor. Staff would see us writing and they never made such an inference. It would say patient engages in writing behavior. Writing behavior being one subset of crazy schizophrenic behavior that people engage in when they’re nutsy.

Alexis Pedrick: Susannah found her second pseudopatient through Bill Underwood, and his experience was very different from both David and Bill’s.

Harry Lando: I’m Harry Lando. I knew David Rosenhan because he was my major professor when I was at Stanford. I was taking this small seminar from Rosenhan, and in that seminar he talked up the study. I also remember he invited us over to his house, uh, for dinner. And his wife made this fantastic gourmet meal and it just, you know, it sounded like kind of an exciting opportunity. And so, you know, Bill and I decided to go ahead with it.

Alexis Pedrick: Harry called up his hospital from a phone booth in San Francisco and gave the same script. He’d been hearing voices, dull, empty, thud.

Harry Lando: A psychiatrist from the hospital interviewed me right then and there in the phone booth, and the psychiatrist got the impression that I might be suicidal. He kept saying, you’re forcing my hand. I was nervous. I answered his questions. I’m sure I didn’t deliberately say anything that would suggest I was suicidal.

Alexis Pedrick: He was ultimately diagnosed with chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia.

Harry Lando: I later understood that that’s kind of a wastebasket diagnosis, kind of a catch all.

Alexis Pedrick: Harry knew his experience was going to be different as soon as he walked into the hospital.

Harry Lando: You get a sense of a place, and it just was a benign atmosphere. It was not dark and dingy. I had visited Bill before that, and it was just an incredibly depressing environment. This was well lit, open, the doors were not locked. And so immediately there was a, I think, a much more comforting vibe.

Alexis Pedrick: Even Harry’s accidental experience with Thorazine was different.

Harry Lando: And Rosenhan had told us about tonguing pills and so forth, not swallowing them, but that first night they gave me liquid Thorazine, which I was not going to tongue, and I think I was so wired that I didn’t even notice any effect of the Thorazine. I just remember, I think, feeling surprisingly calm.

Alexis Pedrick: Surprisingly calm is how you could sum up Harry’s entire story.

Harry Lando: I felt very comfortable in the hospital. Rosenhan talked about for the nurse’s station being off limits, which was not at all true here. You know, we would go in, we used to have jam sessions with the nurses. You know, they were amazingly approachable. I even developed a serious crush on one of the nurses. The ways that Rosenhan described his experience, that was not going to happen with him. There was a patient whose wife came out from New York on the bus and got to San Francisco, had no money, no place to stay, and a nurse put her up in her own home. And I feel myself being emotional when I actually say that.

Alexis Pedrick: All of this seemed to have a positive effect on the other patients.

Harry Lando: One of the things I really saw was a lot of empathy and caring among the patients for other patients. Often, you know, a new patient would come in highly agitated, and then usually within 24 hours they would calm down significantly. But there was a patient that came in, and we were doing group therapy and stuff, and she turned her chair away, you know, not facing the group, and she kept saying she’s been damned by God, and other people who were in the group were, you know, quoting Bible passages at her saying God is all forgiving these kind of things.

Alexis Pedrick: Rosenhan was surprised by Harry’s experience and intrigued.

Harry Lando: He seemed so excited that I was having the experience I was having and kept talking about how he wanted to do more with that and whatever. And then that never happened. And so the next thing I knew, the Science article had come out and I was a footnote.

Alexis Pedrick: And this is where things take a turn. David Rosenhan didn’t include Harry Lando in the study. Instead, he wrote in a footnote, “Data from a ninth pseudopatient are not incorporated in the report because, although his sanity went undetected, he falsified aspects of his personal history. His experimental behaviors, therefore, were not identical to those of the other pseudopatients.” Harry felt terrible, like he had somehow failed.

Harry Lando: I think that I felt like at that time that, yeah, I was responsible because I had had details that were not accurate, even though I made no effort to act in an abnormal way when I was in the hospital.

Alexis Pedrick: But Harry didn’t fail. It was only years later when Susannah Cahalan interviewed him that he got the full picture.

Harry Lando: There were things I took at face value that turned out not to be accurate. And it became pretty clear that if I had had an experience similar to Bill’s, that I would have been included and Susannah found that I had been in an earlier draft. It just didn’t fit with his thesis.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Three. The Fraud.

Not including Harry in the study seemed a bit suspect, but there were other things that caught Susannah’s attention too.

Susannah Cahalan: What was interesting to me was, in the timeline of when this would have been squared away, he would have been one of the final people involved, because the paper was actually submitted to Science shortly thereafter. So I thought, there is a lot of mistakes here.

Alexis Pedrick: David Rosenhan wrote in the study that a legal document called a writ of habeas corpus was prepared for each of the entering pseudopatients during any every hospitalization. Basically, if one of the hospitals refused to release a pseudopatient, a lawyer would present this document and they’d be forced to go to court where the whole charade would be unveiled and the pseudopatient would be released. But Susannah found they didn’t exist.

Susannah Cahalan: There were no writs of habeas corpus that David Rosenhan claimed to have filed that was never done. There seemed to be no safety protocols in place.

Alexis Pedrick: And then there was this question. Why didn’t Rosenhan warn Bill Underwood about the potential hazard of Thorazine’s coating melting and burning your tongue?

Susannah Cahalan: And I thought, gosh, if this is his eighth pseudopatient, he should have learned a little bit by then. You know, it just was strange to me.

Alexis Pedrick: The more Susannah dug, the sloppier things got. Numbers seemed off. Rosenhan wrote in the study that the pseudopatients were administered 2,000 pills, but in an interview, he says 5,000.

Susannah Cahalan: The numbers would be, like, staggeringly off. And also kind of, ridiculous too. I, you know, there would be a hospital that would be enormous. And, and I’d look at the area they’d say, and there’d be no hospital that in that area that fit that bill. So there was just kind of all of these signs. I didn’t know where they were pointing, but they were not, they didn’t make sense for a kind of a legitimate Science article to have this many kind of inconsistencies.

Alexis Pedrick: But it was one interview that started to unravel the entire story. During a phone call, a psychologist who had worked with David Rosenhan told Susannah a funny story about him.

Susannah Cahalan: He had these parties, and at one party, Rosenhan was kind of regaling the room with his stories of being a pseudopatient, and he marched everyone upstairs, opened his closet, and he took out a wig. And he said, this was the wig that I wore as a pseudopatient. And I’m on the phone, we’re laughing about him kind of dancing around, putting the wig on and I thanked him for the end of the interview. I hung up the phone. And then I remembered that there was a medical record that was, uh, you know, of the David Rosenhan pseudopatient. And there was a picture attached to that record. And it’s very grainy. It’s very hard to see clearly. But you can very much see. The light gleaming off his bald head. He was not wearing any wig at all. That was a complete fabrication. And it was so strange to me to lie about that. Why would he lie about that?

Alexis Pedrick: If you lie about a wig, what else are you lying about? Something big, it turns out.

Susannah Cahalan: I think the smoking gun for me was the medical record. So that was just astounding. And when I saw that, that was when I knew I had something more serious going on here than a wig.

Alexis Pedrick: Rosenhan didn’t include his or anyone’s whole medical report in the final Science article.The reason he gave was that he didn’t want to reveal which hospitals they stayed in. But he does include a whole paragraph, quoted directly from someone’s medical report, and by comparing it to things Rosenhan said about his own stay, it’s clear that it was his own. Here’s what the paragraph in the Science article says, “This white, 39 year old male manifests a long history of considerable ambivalence in close relationships. A warm relationship with his mother cools during his adolescence.” And here’s what David Rosenhan said in an interview.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: He asked me such questions as, how did you get along with your parents? And I told them my mother was my very close friend while I was growing up, but the relationship sort of cooled when adolescence came.

Alexis Pedrick: The Science article quote from the medical record goes on. “A distant relationship to his father is described as becoming very intense.”

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: My father and I weren’t such good friends when I was a kid, but he was my best friend during my adolescence and early adulthood until he died.

Alexis Pedrick: “His attempts to control emotionality are punctuated by angry outbursts and spankings.”

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: Do you ever spank your children? To which I responded, my son twice, my daughter once, in fact. He never inquired under what conditions do you spank your children, or did you spank your children? What becomes very interesting is how they interpret it. So you take this, what I consider to be unexceptional case history, uh, was interpreted as reflecting my enormous ambivalence in interpersonal relationships.

Alexis Pedrick: This excerpt from Rosenhan’s medical record was used in the Science article as evidence that once someone was inside the walls of a mental institution, psychiatrists were primed to see mental illness. There was just one problem.

Susannah Cahalan: So you have a whole part that is supposedly word for word from the medical record. It was very Freudian. It was psychoanalytic. It was about the father and the mother and this relationship, and it was entirely made up.

Alexis Pedrick: Susannah had David Rosenhan’s actual medical record. And after the wig revelation, she looked more closely at it. It revealed the hospital where he’d been, Haverford State Hospital. And at first, it tracks with the symptoms every pseudo patient was supposed to claim. But then Rosenhan went off script. Way off.

Susannah Cahalan: I found the medical record that Rosenhan had said things like, I put copper pots over my ears to drown out the noises, and that he had been suicidal for many months. I mean, these are very serious symptoms.

Alexis Pedrick: “He has felt that he is sensitive to radio signals and hear what people are thinking. He realized that these experiences are unreal, but cannot accept their reality. One reason for coming to the hospital was because things are quote, ‘better insulated in a hospital.’”

Susannah Cahalan: These are very serious symptoms, and understandably, a psychiatrist looking at it would be concerned. And, you know, even psychiatrists that I showed today, they said the suicidality would be an issue. That there’s such a crisis in mental health care, they probably wouldn’t get a bed. But if there was a bed available, maybe he would have gotten a bed today. The suicidality thing really shocked me.

Alexis Pedrick: None of these details made it into the article itself, or any of the scores of lectures or interviews Rosenhan gave after the Science article was published.

Susannah Cahalan: It was a fiction, it was a fantasy that, that, that, that Rosenhan made up, and he published it in Science. And it was shocking to me.

Alexis Pedrick: Finding the real medical report gave Susannah a whole new level of skepticism about the study, and she realized something else was off.

Susannah Cahalan: Almost every detail in the article was about David Rosenhan’s time in the hospital from his Haverford State Hospital visit in ‘69. And I know that because I had his notes from Haverford. And, oh, there are almost no other details about the other seven. However, there were still some details about Harry’s hospitalization that were used in the study, one involving flirting with a nurse.

Harry Lando: He kind of had it both ways because I was a footnote, I wasn’t included, but there were several references in the article to what was very clearly my experience.

Alexis Pedrick: Remember, Harry’s data was dropped from the study because it didn’t fit Rosenhan’s thesis.

Susannah Cahalan: But Harry made it in? Wouldn’t you think he’d have enough detail from the other six to not have to use the one he claims to have discarded? That really kind of pinged something in me, and I really started to look at the archive and the information that it had in a different light.

Alexis Pedrick: Throughout the years she worked on her book, Susannah tried over and over again to identify the other six pseudopatients. She wrote to medical journals looking for people who knew anything. She made a speech at an American Psychiatric Association meeting. She even hired a private detective and the only two pseudopatients any of these efforts ever pointed to were Bill Underwood and Harry Lando. Still, Susannah held out hope that someone would read the book and come forward. But the book came out in 2019.

Susannah Cahalan: No one’s come forward. Like, someone would’ve, and now I’ve completely given it up because the book’s come out.

Alexis Pedrick: We may never know definitively if there were any other pseudo patients besides David Rosenhan, Bill Underwood, and Harry Lando and his footnote. But here’s what we do know. David Rosenhan attended a conference in 1970 where an editor from Science was also present.

Susannah Cahalan: And I believe, this is conjecture, but I believe that’s where science got their knowledge about this and said to him, make this into a study, add some other people into this, and we’ll publish this. That’s my theory. And I think he had a harder time convincing people to get to do that than he thought he would. And I think kind of it was down to the wire, and he was putting a lot of pressure. Harry remembers that he was putting a lot of pressure on the students to take part in the study, and people really didn’t want a lot to do with it. And I think he was kind of back against the wall and either he delivered or he didn’t.

Alexis Pedrick: After the Science article came out, Rosenhan got offered a book deal.

Susannah Cahalan: The big book was the next step to really cement your legacy. He got a deal. He paid part of his advance. And he never delivered the book. So I had the book. It was almost, I would say, three quarters the way done, maybe, maybe a little bit less.

Alexis Pedrick: It was here, in the unfinished book, where Susannah found all the details about the other pseudopatients.

Susannah Cahalan: Now this is an interesting part. So the detailed notes seemed to come while he was writing the book.

Alexis Pedrick: That is, after the study came out.

Susannah Cahalan: Interestingly, the other pseudopatients, though there were tons of details, all of them felt off. It didn’t feel real. The parts that felt real really were David’s own experience. That was really kind of jumped off the page and, and really kind of shined, but the rest just really did not make much sense.

Alexis Pedrick: One of the pseudopatients was described as a famous abstract painter, the only one admitted to a private psychiatric facility. But Susannah started pulling one thread from Rosenhan’s notes about her, and it quickly came apart. First, Rosenhan claimed that he paid for the stay himself, but she was supposedly there for 53 days, which would have been extremely expensive.

Then there was this. David wrote that during her stay, the hospital invited him to come consult on a case, and it just happened to be her case. What a coincidence, especially since Rosenhan wasn’t even a clinical psychologist. Susannah also found something else odd. Letters from people David knew who had really been patients in psychiatric hospitals were tucked into the notes for his book, and some of those details were surprisingly similar to some of his supposed pseudo patients.

When Susannah started writing the book, she really admired David Rosenhan and wanted to tell the stories of the pseudopatients.

Susannah Cahalan: I didn’t have any radar about this. I wasn’t like, oh, I’m going to unmask this. You know, I’m going to figure out the truth. It was more like, who would do this and why? And how did it affect the rest of their lives?

Alexis Pedrick: After the book came out, Susannah went out to dinner with two of the people who knew David best, two psychologists named Florence Keller and Lee Ross.

Susannah Cahalan: She was the one who said to me, maybe he made this all up. And also, you know, Lee Ross is this great kind of giant in psychology, so insightful and smart. And he was pretty convinced Rosenhan had at least fabricated parts of the, of his study. I mean, I think that’s undeniable. The question is how much really.

Alexis Pedrick: Chapter Four. The Aftermath.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: Do you think that Asians can, can get better going into institutions today as they are in this country? I really don’t. By and large, I think that psychiatric hospitals are non therapeutic and would look forward to their being closed.

Alexis Pedrick: Psychiatric hospitals reached their peak numbers in 1955 and then gradually started declining into the ‘60s before Rosenhan’s study.

Susannah Cahalan: What happened with Rosenhan is it started the process of uniting left and right over this issue. You have this kind of financial perspective of, well, we’ll save money by closing these hospitals. Then you have this patient rights perspective of people shouldn’t be there.

Archived Audio of Dr. Rosenhan in Conversation: If you’re saying that mental institutions are not good places for people with emotional or mental problems to be, what can we do to help people with problems? You’ve got me over a barrel, Carol. I’m not sure. It’s so much easier to say no about something than to say yes.

Alexis Pedrick: But Rosenhan did have a prime example of how a psychiatric facility could be therapeutic, in Harry Lando’s experience.

Harry Lando: And I guess that’s where now I would really resent Rosenhan because he painted this incredibly negative picture and the reality is that in general, that was accurate, but to fail to recognize the exceptions and that there were places that were really good was an incredible lost opportunity, and I think it’s had major repercussions.

Alexis Pedrick: Rosenhan got his wish. Psychiatric hospitals closed, and for a lot of them, it was good riddance.

Susannah Cahalan: They should have disappeared because these were horrible places, but what was left was just kind of an emptiness. You know, what do you do now?

Alexis Pedrick: When asylums were closed, they were supposed to be replaced by a model called community care, and in theory, it’s great. Everyone who needs psychiatric care can get it while living in their own community, but it never really materialized. And today, the major centers of inpatient psychiatry in the U.S. are in prisons. But it wasn’t just the asylum system that felt the impact of the study. It prompted psychiatrists to completely change their system of diagnosing. They set out to revise psychiatry’s bible, the book that categorizes mental illness. It’s called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , or the DSM. There had already been two versions, now they needed another one.

Susannah Cahalan: They started the DSM III right after. This study was published and in the resulting publicity, so it was definitely a reaction to what was going on.

Alexis Pedrick: A serious, anti Freudian, biologically minded psychiatrist was tapped to lead the revision, Robert Spitzer. His goal was to get rid of the Freudian influence, remove the psychobabble.

Susannah Cahalan: In general, it was a reaction to this kind of very loose, Freudian, uh, cchizophrenia could be a million different things under the Freudian model.

Andrew Scull: The Freudians saw symptoms as the tip of the iceberg, the thing you needed to get behind. What Spitzer did was say, no, the symptoms are the disease, basically.

Alexis Pedrick: Robert Spitzer was not a fan of David Rosenhan or his study. He was a man of hard data, references, and classification. The vagueness of the Science article screamed sham to him, and he let Everyone in his orbit know it

Susannah Cahalan: Spitzer wrote two, maybe three articles. I think there were actually three articles about the study and he actually, he hosted a conference based on taking down this study. And he was the kind of guy I think that once he got something in his crosshairs, he wanted to chase it down. And he was really a tough guy and he really went after this study big time.

Alexis Pedrick: The problem was that his audience was other psychiatrists. So, it didn’t get out into the mainstream like Rosenhan’s study had. So, all he could do was use the opportunity to rewrite the DSM.

Susannah Cahalan: Rosenhan was a big topic of conversation why they were writing criteria for the DSM III. So they would constantly ask themselves, Would this pass the Rosenhan test? He was a specter haunting the creation of this, like, foundational biblical document for psychiatry as it stands today.

Alexis Pedrick: But Susannah found something else kind of shocking in the files.

Susannah Cahalan: Spitzer had the smoking gun.

Alexis Pedrick: Spitzer had Rosenhan’s real medical record the whole time. The one that said he wore a copper pot to drown out the audio hallucinations. The one that said he was suicidal. And Susannah knows this because she found letters between Spitzer and Rosenhan.

Susannah Cahalan: The vitriolic back and forth.

Alexis Pedrick: Where Spitzer let him know he had it. When “On Being Sane in Insane Places” was published, the psychiatrist from Haverford State Hospital who treated David Rosenhan was so outraged by the fake medical report that he leaked the real one to Robert Spitzer.

Susannah Cahalan: And in fact, Rosenhan was so scared when he heard that he had that. He was getting very upset in this correspondence.

Alexis Pedrick: It was such a crucial piece of evidence for Robert Spitzer.

Susannah Cahalan: He hated this study so much. He had conferences about it, but he had the one document that would just completely destroy the paper. But Spitzer put that medical record away and never discussed it publicly.

Alexis Pedrick: The obvious question is, why? Why didn’t he kill the study he hated when he had the chance?