An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Emotional Expression: Advances in Basic Emotion Theory

Dacher keltner, disa sauter, jessica tracy.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Issue date 2019 Jun.

In this article, we review recent developments in the study of emotional expression within a basic emotion framework. Dozens of new studies find that upwards of 20 emotions are signaled in multimodal and dynamic patterns of expressive behavior. Moving beyond word to stimulus matching paradigms, new studies are detailing the more nuanced and complex processes involved in emotion recognition and the structure of how people perceive emotional expression. Finally, we consider new studies documenting contextual influences upon emotion recognition. We conclude by extending these recent findings to questions about emotion-related physiology and the mammalian precursors of human emotion.

Introduction

Basic Emotion Theory (BET) is guided by convergent analogies found in the writings of scientists working in different traditions: Emotions are a “grammar of social living” that situate the self within a social and moral order; they structure interactions, like scripts in pieces of fiction, in relationships that matter ( Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989 ; Oatley, 2004 ). In more specific terms, within BET emotions are thought of as distinct and brief states involving physiological, subjective, and expressive components that enable humans to respond in ways that are typically adaptive in relation to evolutionarily significant problems, from negotiating status hierarchies to avoiding peril to taking care of vulnerable offspring ( Ekman, 1992 ; Ekman & Cordaro, 2011 ; Keltner & Lerner, 2010 ; Shariff & Tracy, 2011 ; van Kleef, 2016 ).

These core assumptions of BET have been foundational to new empirical advances, ranging from the study of a broad number of previously unexplored specific positive emotions (e.g., Campos et al., 2013 ; Shiota et al., 2017 ) to progress in understanding basic mechanisms of emotion-related appraisal, language, development, and central and peripheral nervous system physiology (e.g., Lench et al., 2011 ; Nummenmaa, & Saarimäki, 2017 ).

BET has also been central to the study of emotional expression. It was a focus, of course, of Darwin, who was an inspiration of the rich literature that we summarize here. In the simplest of terms, Basic Emotion Theory posits that nonverbal expressions of emotion share five properties. 1) They are brief, coherent patterns of behavior that tend to covary with distinct subjective experiences; 2) they signal the current emotional state, intentions, and/or assessment of the eliciting situation of the individual; 3) they manifest some degree of cross-cultural similarity in both production and recognition; 4) they find evolutionary precursors in the behaviors of other mammals in contexts similar to the contexts humans encounter (e.g., when signaling adversarial or cooperative intentions); and 5) they tend to covary with emotion-related physiological responses ( Ekman & Davidson, 1994 ; Hess & Fischer, 2013 ; Keltner & Haidt, 2001 ; Keltner & Lerner, 2010 ; Matsumoto et al., 2008 ; Shariff & Tracy, 2011 ).

A first wave of BET-inspired studies on emotional expression find their provenance in the studies of Ekman and Friesen in New Guinea ( Ekman, Sorenson, & Friesen, 1969 ), with which many are now familiar, but whose details are worth recalling. Using still photographs of prototypical emotional facial expressions, Ekman and Friesen were able to document some degree of universality in the production and recognition of a limited set of “basic” emotions, including anger, fear, happiness, sadness, disgust, and surprise (for review, see Matsumoto et al., 2008 ). This study inspired hundreds like it, and led to the replicated finding that observers could reliably identify with some degree of consistency these six emotions in static photos of facial muscle configurations (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2001).

Clearly there is much more to emotional expression - both in the behavior people emit and how they judge it - than matching static images of facial muscle movement configurations to words or situations (as in the original Ekman and Friesen work). People clearly express emotions in more ways than in facial muscle movements, and rely on more than just single words or scenarios to make sense of emotional expression. The Ekman and Friesen work inspired several robust critiques. Questions have been raised about biases in the forced choice paradigms, the robustness of those results from forced studies, and the reliance upon such exaggerated, stereotypical expressions ( Russell, 1994 ; Matsumoto & Hwang, 2017 ; Nelson & Russell, 2013 ). Reviews have revealed that the relationship between self-reports of subjective experience and facial muscle movements is more modest than perhaps assumed in BET ( Duran, Reisenzen, & Fernandez-Dols, 2017 ). More recent data raises questions about the degree to which people from remote cultures actually recognize emotion in static photos of the six emotions ( Crivelli et al., 2016 ). Particularly generative is Fridlund’s critique of BET, summarized in his Behavioral Ecological theory (BECV, see Fridlund, 1991 , this volume). Fridlund’s theorizing, steeped in evolutionary accounts of nonhuman display, argues that human facial displays did not evolve to signal interior feeling, as presupposed in BET, but social intentions or motives instead (see Parkinson, 2005 , for a detailed review of BET and BECV claims). This theorizing has inspired studies of how people infer intentions, feelings, and appraisals from expressive behavior, which we consider later.

The Ekman and Friesen empirical work - the focus on how people label static images of facial muscle configurations - has inspired another class of developments in the field that are still guided by the core assumptions of BET but that move beyond the study of the recognition of static images of facial expressions of six emotions. It is these developments that we focus on here. We attend, in particular, to three areas of empirical advance. A first concerns the nature of emotional expression, which has been shown to include much more than six distinct facial expressions, and, in fact, upwards of 20 multimodal expressions. A second set of advances is found in the study of emotion perception, which concerns the processes by which social perceivers derive meaning from emotional expressions of different kinds. Guided by the aforementioned critiques of the Ekman and Friesen studies, the field has moved beyond relying exclusively on forced choice labeling of expressions, and progress is being made in understanding how social perceivers infer intentions, motives, action tendencies, and relational properties of signaler and perceiver in brief expressions of emotion. Finally, arising out of the functional foundation of BET has emerged a new line of inquiry—how expressions coordinateinteractions between individuals (e.g., Keltner & Kring, 1998 ; Niedenthal et al., 2015; van Kleef, Cheshin, & Fischer, 2016 ). This line of work most explicitly returns to a core notion of BET— that emotions are the grammar of social living—to detail how brief emotional expressions, in single modalities and in multimodal forms, coordinate interactions within meaningful relationships, such as those between parent and child, romantic partners and friends, or individuals within status hierarchies (e.g., for review, see van Kleef, 2016 ).

Advances in understanding the nature of emotional expression

Emotional expressions are multimodal, dynamic patterns of behavior.

Central to Basic Emotion Theory is the assumption that emotions enable the individual to respond adaptively to evolutionarily significant threats and opportunities in the environment, such as the cry of offspring, a threat from an adversary, or a potentially available sexual partner ( Ekman, 1992 ; Keltner & Haidt, 2003 ). Emotions enable such responses primarily through shifts in peripheral physiology ( Levenson, Ekman & Friesen, 1990 ), patterns of cognition ( Oveis, Horberg, & Keltner, 2010 ), movements of the body (e.g., the proverbial fight or flight response), and expressive behaviors that coordinate social interactions through the information they convey and the responses the evoke in others (e.g., Keltner & Kring, 1998 ; van Kleef, 2009 ).

Within this framework, emotions are fundamentally about instigating action and changing the probabilities of future actions ( Frijda, 1986 ). Emotions enable people to react to significant stimuli (in the environment or within themselves), with complex patterns of behavior involving multiple modalities - facial muscle movements, vocal cues, bodily movements, gesture, posture, and so on. For example, studies of the emotion sympathy find that this brief state involves bodily movements forward, soothing tactile behavior, oblique eyebrows, a fixed pattern of gaze, vocalizations, and skin-to-skin contact when sympathy leads to embrace ( Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010 ).

Early studies of emotional expression largely focused on whether perceivers could infer emotions from static portrayals of prototypical configurations of facial muscles thought to convey anger, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise, and happiness ( Ekman, 1994 ; Russell, 1994 ). The last 20 years of scientific study has moved significantly beyond static facial portrayals of these six emotions, revealing that emotional expressions are multimodal, dynamic patterns of behavior , involving facial action, vocalization, bodily movement, gaze, gesture, head movements, touch, autonomic response, and even scent ( Keltner et al., 2016 ).

Notably, the notion that emotional expressions are multimodal patterns of behavior was evident already in Charles Darwin’s original, rich descriptions of the expressions of over 40 emotional states ( Keltner, 2009 ), as illustrated in Table 1 (focusing specifically on positive emotions). As is evident in the table, Darwin focused on extended and multimodal dynamic patterns of behavior, that involve not only facial muscle movements but also changes in gaze, body movements, respiration, gestures, hand movements, the voice, tactile contact, and autonomic responses (e.g., tears).

Darwin’s descriptions of the expressive behavior ofpositive emotions.

Early studies, as we have noted, focused almost exclusively on facial muscle movements. The more recent consideration of other modalities of communication has greatly expanded the field’s understanding of emotional expression. Studies of emotional expressions associated with experiences of embarrassment, shame, pride, and love have discerned distinct expressions of these emotions by incorporating measurements of gaze activity (e.g., the gaze aversion of shame and embarrassment), body movements (e.g., the chest expansion of pride and the open posture of love), hand activity (e.g., the face touch of embarrassment and open handed gesture of love), and movements of the head, such as the head tilt back during expressions of pride ( Keltner, 1995 ; Tracy & Robins, 2004 ; 2007 ). These findings have prompted studies to systematically characterize how emotions are communicated in movements of the body ( Dael, Mortillaro, & Scherer, 2012 ; Gross, Crane, & Fredrickson, 2010 ) and gaze ( Sander et al., 2007 ). These developments of the study of emotional expression are clearly in keeping with Darwin’s more comprehensive analysis, and his suggestion that there should be signal value in how emotions are conveyed from a vast array of communicative behaviors, from simple movements of the hands to shifts in body posture to head movements.

To take one example of a major stream of research in this vein, the human voice has consistently been documented to be a rich modality of emotional expression, as anticipated in the seminal theorizing of Klaus Scherer ( Scherer, 1986 ). To study whether people can communicate emotions with the voice, researchers have relied on two methods. In one, people, often trained actors, attempt to express different emotions in prosody, the tone and rhythm of our speech, while reading nonsense syllables or neutral passages of text ( Banse & Scherer, 1996 ; Juslin & Laukka, 2003 ). These samples of emotion-related prosody are then presented to listeners, who select from a series of options the term that best matches the emotion conveyed in the speech output. For example, Petri Laukka, Hillary Elfenbein and their colleagues had actors from five countries - India, USA, Singapore, Australia, and Kenya - attempt to convey 11 different emotions -- anger, contempt, fear, happiness, interest, neutral, sexual lust, pride, relief, sadness, and shame -- while uttering sentences of neutral content (e.g., “Let me tell you something”). They then presented these clips of emotional prosody to people in different cultures, and found that listeners could recognize most of the intended states when asked to label the sounds’ emotional content (e.g., Laukka et al., 2016 ). These findings build upon a review of 60 earlier studies of this kind, which found that listeners can judge five different emotions in the prosody that accompanies speech—anger, fear, happiness, sadness, and tenderness—with accuracy rates that approach 70% ( Juslin & Laukka, 2003 ). Judgments are most accurate when listeners hear members of their own culture ( Pell et al., 2009 ).

In a second line of study of vocal expression, participants communicate emotions through vocal bursts, which are brief, non-word utterances that arise between speech incidents. Laughs, shrieks, growls, sighs, oohs, and ahhs, are examples of vocal bursts. In studies of vocal bursts, people are typically given a situation that produces an emotion (e.g., for awe, “you are seeing a large waterfall for the first time”) and asked to communicate that emotion with a brief vocal burst but no words ( Laukka et al., 2013 ; Sauter & Scott, 2007 ; Sauter, Eisner, Calder, & Scott, 2010 ; Simon-Thomas et al., 2009 ). These sounds are then played to listeners, who attempt to label the sound with one of many emotion terms, or to match the sound to the appropriate emotion eliciting situation. As with emotional prosody, people are quite adept at communicating emotions with vocal bursts. For example, Cordaro and colleagues presented vocal bursts of 16 emotions to people in 10 different cultures in Western Europe (Germany, Poland), East Asia (China, Japan, South Korea) and South East Asia (India, Pakistan) ( Cordaro et al., 2016 ). In this study participants were asked to match emotionally rich but simple situations (e.g., someone has insulted you; you hit your leg on a rock) to one of four vocal bursts. Overall, participants were correct in matching stories to vocal bursts of 16 emotions 79% of the time. People in these 10 countries were able to identify vocal bursts of six positive emotions - amusement, awe, contentment, desire, interest, relief, and triumph - and six negative emotions - anger, contempt, disgust, embarrassment, fear, pain, and sadness. Subsequent studies have documented that even in remote cultural groups in Bhutan and Namibia, people are able to reliably discern a number of emotions from vocal bursts ( Cordaro et al., 2016 ; Sauter et al., 2010 ; Sauter, Eisner, Ekman, & Scott, 2015 ).

Yet another modality that has been of increasingly systematic focus in the study of emotional expression is touch. In one line of research inspired by BET, Hertenstein and colleagues ( Hertenstein et al., 2006 , 2009 ) brought an encoder (the person charged with expressing emotion via touch) and decoder (the person being touched) to the lab. The encoder and decoder sat at a table, separated by an opaque black curtain which prevented communication other than touch. The encoder was given a list of emotions and asked to make contact with the decoder on the arm to communicate each emotion, using any form of touch. The decoder could not see any part of the touch because his or her arm was positioned on the encoder’s side of the curtain. After each touch, the decoder selected from 13 response options the term that best described what the encoder was communicating. Participants were found to reliably communicate anger, disgust, and fear from a brief one- or two-second touch of another’s forearm, as well as love, gratitude, and sympathy (see also Piff et al., 2012 , for replication). Emotions like embarrassment, awe, and sadness were not reliably communicated via touch. In other research, it was found that people are more reliable in communicating emotion through touch when allowed to touch other regions of the body than the arm ( Hertenstein et al., 2009 ). Finally, there are cross-cultural similarities in which emotions can be conveyed through tactile contact (see Hertenstein et al., 2009 ).

There are also emerging literatures on potential autonomic signals of emotion, including the blush ( van Dijk et al, 2009 ), the chills ( Maruskin et al, 2012 ), and tears ( Balsters, Krahmer, Swerts, & Vingerhoets, 2013 ; Vingerhoets & Bylsma, 2016 ). Thinking of emotional expressions as dynamic multimodal patterns of behavior points to intriguing new questions (e.g., Aviezer, Trope, & Todorov, 2012 ). What is the relative contribution of different modalities to the perception and signal value of emotional expressions (e.g., Flack, 2006 ; Scherer & Ellgring, 2007 )? Why is it that certain emotions are more reliably signaled in multiple modalities, whereas other emotions are only recognized from one modality? For example, sympathy is reliably signaled in touch and the voice, but less so in the face ( Goetz et al., 2010 ). It is nearly impossible to communicate embarrassment through touch, but it is reliably communicated in patterns of gaze, head, and facial behavior ( App, McIntosh, Reed, & Hertenstein, 2011 ).

There are Expressions of More Emotions than the “Basic” Six

Critical to Basic Emotions Theory is the question of which emotions have distinctive signals. Evidence germane to this question informs taxonomies of emotion (e.g., Keltner & Lerner, 2010 ). As evident in the previous section, evidence has emerged revealing that emotions beyond the “basic six” have distinct multimodal and dynamic expressions, including emotions such as embarrassment, pride, shame, and love. In recent years, dozens of studies have contributed to this line of work differentiating expressions of a wider range of emotions (e.g., Keltner et al., 2016 ; Laukka et al, 2013 ; Sauter & Scott, 2007 ; Tracy & Robins, 2004 ). Three methods have been at the heart of this new development. A first is emotion encoding studies, where behavioral analyses ascertain whether the experience of closely related emotions, such as sympathy or distress, or love or desire, or embarrassment, shame, and amusement, are expressed in different patterns of behavior (e.g., for review, see Matsumoto et al., 2008 ).

A second approach is found in emotion production studies. In these studies, participants are given a prompt, most typically the definition of an emotion or an emotion-specific story, and asked to communicate each emotion nonverbally. For example, in one recent study, participants in five different cultures - China, India, Japan, Korea, and the USA - heard twenty-two emotion- specific situations in their native language and were asked to express the emotion in whatever fashion they desired, which could include facial, vocal, or bodily expressions; the only requirement was that the expressions be nonverbal ( Cordaro et al., 2018 ). Over 5500 facial expressions, bodily movements, gaze movements, hand gestures, and patterns of breathing were coded using an expanded Facial Action Coding System ( Ekman & Friesen, 1978 ), and a large subset of these was analyzed for patterns across and within cultures. For the 22 emotions that were studied, certain configurations of expressive behaviors were observed with above chance frequency across all five cultural groups, which one might think of as the prototypical elements of the multimodal expression. Across cultures the expression of awe, for example, tended to involve the widening of the eyes and a smile as well as a head movement up. Across cultures, head nods expressed interest. Confusion was generally expressed with behaviors including furrowed brows, narrowed eyes, and a head tilt. Overall, 22 emotions were found to have distinct, multimodal expressions.

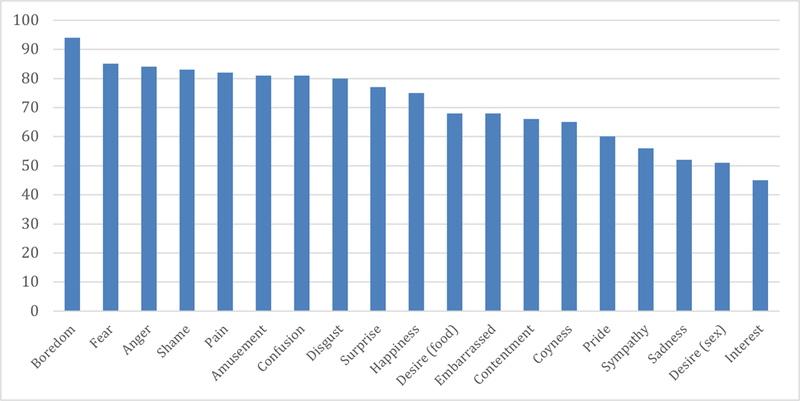

A third approach to documenting distinct expressions is with emotion recognition paradigms, in which participants attempt to map an emotion concept - in their own words, in stories, or emotion terms - to different emotion-expressions. Based on the advances in understanding facial expression, Cordaro took photographs of prototypical facial-bodily expressions 18 different emotions and then gathered data from 10 different cultures, ranging from Pakistan to New Zealand ( Keltner & Cordaro, 2016 ). In this study, as in the Ekman and Friesen work, participants were presented with emotion specific scenarios for each of 19 different emotions (e.g., for pain: “this person just stubbed their toe on a rock”). For each scenario they were required to choose from one of four static photos of facial/bodily expressions the photo that best captured the scenario. Table 2 presents examples and descriptions of the photos in this study. As can be seen from the recognition rates presented in Figure 1 , the landscape of emotional expression in the face and body is increasingly rich.

Facial expression examples, FACS action units, and physical descriptions for each expression.

Recognition rates across five cultures in identifying 19 emotions from facial/bodily expressions portrayed in static photos (from Keltner & Cordaro, 2016 ).

In Table 3 , we summarize this new literature on multi modal expressions beyond the basic 6, indicating whether studies reveal that the facial, bodily, vocal, tactile, and music-related expressions of each emotion can be differentiated from expressions of other emotions. In the respective columns, “yes” indicates that the evidence suggests that the emotion is communicated in a modality at above chance levels; “no” indicates that the emotion cannot be reliably communicated in the modality. These data make the case for distinct expression or 24 emotional states when different modalities are considered. We note, however, that these findings leave open the possibility that there will be emotions with distinct multimodal expressions that are not readily recognized, and that few if any studies have looked at how reliably these emotions are identified when all modalities are considered.

Evidence related to the expression of emotion in different modalities.

Shiota, Campos, & Keltner (2003) .

Keltner & Bonanno (1997) .

Shiota, Keltner, Mossman (2007) .

Hejmadi, Davidson, & Rozin (2000) .

Reddy (2000) .

Reddy (2005) .

Bretherton & Ainsworth (1974).

Gonzaga et al. (2006) .

Keltner & Shiota (2003) .

Keltner & Buswell (1997) .

Keltner (1996) .

Ekman & Rosenberg (1997) .

Silvia (2008) .

Reeve (1993) .

Prkachin (1992) .

Williams (2002) .

Grunau & Craig (1987) .

Botvinick, et al. (2005) .

Tracy & Robins (2004) .

Tracy & Matsumoto (2008) .

Rozin & Cohen (2003) .

Ekman & Friesen (1986) .

Ekman (1992) .

Levenson, Ekman, & Friesen (1990) .

Simon- Thomas, et al. (2009) .

Sauter & Scott (2007) .

Schroder (2003).

Sauter, Eisner, Ekman, & Scott (2010) .

Dubois et al. (2008) .

Hertenstein et al. (2009) .

Hertenstein et al. (2006) .

Juslin & Laukka (2003) .

Piff, et al., (2012) .

Tracy, Robins, & Shriber (2009) .

Tracy & Robins (2008) .

Within category prototypes, variations, and cultural dialects

An early assertion of BET is that emotions are expressed not only in prototypical expressions involving the behaviors common to that category, but also via within-category variations of expressions ( Ekman, 1992 ). For example, Ekman observed that alongside the prototype of an anger expression – furrowed brow, raised upper eyelids, lip tighten and press together – there are upwards of 60 variants of anger-elated expressions ( Ekman, 1993 ). More generally, within an emotion category variations might include additional behaviors – an eye brow flash in the embarrassment expression - or fewer of the prototypical elements of an expression - an expression of anger that only involves the lip press and tightening, but no movement in the eye brow region.

Empirical studies have been fruitfully guided by this analysis of within category variation in emotional expression. For example, early studies of the expressive behavior of embarrassment documented a multimodal prototypical expression that included gaze down, head movement down, awkward smile. Further, naive observers were better able to recognize expressions of embarrassment as they increasingly resembled the prototypical expression ( Keltner, 1995 ). A similar analysis has been taken to the analysis of pride, uncovering a prototypical expression and variations (see Tracy & Robins, 2007 ). Likewise, studies find that within the category of laughter, there are multiple variations ( Szameitat et al., 2009 ). Studies of emotion-related tactile contact similarly find variation in the patterns of tactile behavior (location, pressure, configuration of hand) within the expression of one emotion, such as gratitude or sympathy, and, as in studies of facial and bodily movement, observer accuracy varies depending on which particular expression is observed ( Hertenstein et al., 2006 ).

There is clear precedent in BET that there is not necessarily a one-to-one correspondence between the occurrence of an emotion and a prototypical expression (see Ekman, 1992 ). Rather, emotions are expressed in prototypical multimodal patterns of behavior, with striking variations. To make sense of emotion-related prototypes and within category variations, Hillary Elfenbein, Ursula Hess, and their colleagues have offered their dialect theory of emotional expression ( Elfenbein, 2013 ; Elfenbein et al., 2007). This theorizing posits that emotional expression is likely to function much like language, such as English, in the sense that languages have elements - select phonemes, words, forms of syntax -- shared by all speakers of the language, as well as dialects, or specific variations of the language in sound and word use that are specific to a geographical region. For example, although standard English is common to the English speaker in England, different regions - London, Newcastle, or the Midlands - are known to speak their own dialects, with unique words, phrases, and accents and forms of prosody.

Several recent studies speak to the prevalence of dialects in emotional expressions (e.g., Cordaro et al., 2018 ; Elfenbein et al., 2007; Laukka et al., 2016 ). In these studies, people from different cultures were given a definition of different emotions or a situation likely to produce the emotion, and then asked to express the emotion with any behavior that feels natural. These patterns of expression were then carefully analyzed for their specific facial, bodily, or vocal behaviors, identifying what is universal and how prevalent culturally specific dialects are. A first generalization of the results is just how pervasive emotion dialects are. For example, in one study that looked at expressions of 22 emotions, every emotion was found to have a dialect specific to the culture, and about 25% of an individual’s expressive behavior across emotions was based on dialect, while around 50% of an individual’s expressive behavior adhered to the universal prototype ( Cordaro et al., 2018 ). Second, dialects appear to be more likely to emerge for emotions that are more directly involved in social interactions, such as anger, happiness, or shame - compared to emotions that are less directly or frequently involved in social interactions, such as disgust or fear (Elfenbein et al., 2007).

Process, Structure, and Contextual Shaping of Emotion Perception

The first wave of science on emotional expression - largely focused on the face - involved emotion recognition studies that most typically entailed participants matching an emotion term, or an emotional-specific story, from a list of options to a specific expression. A meta-analysis of 182 independent samples examining judgments of emotion from facial and other nonverbal cues yielded an average accuracy rate of 58.0% (a large effect size), after correcting for chance guessing ( Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002 ). With respect to vocal expressions of emotion, in a review of over 100 studies largely using single word emotion recognition paradigms, Juslin and Laukka (2003) concluded that listeners can judge at least five different emotions in the voice - anger, fear, happiness, sadness, and tenderness -- with accuracy rates that approach 70% (see Hawk et al., 2009 ; Sauter et al., 2013 ).

These findings have been critiqued, and debate continues about the degree of agreement in the recognition of emotion from expressive behavior ( Nelson & Russell, 2013 ; Russell, 1994 ). Fridlund has also raised theoretical questions about what exactly is signaled by expressive behavior (Fridlund, this volume; Parkinson, 2005 ). Feelings? Intentions? Likely actions? Properties - e.g., of dominance or affiliation - of the relationship between the communicator and perceiver? This critique and theorizing has inspired considerable advances in the conceptualization of the process, structure, and contextual shaping of emotion perception.

The process of emotion perception

Clearly, when an individual encounters emotional expression in others, he or she is likely to engage in complex inferential processes that involve more than the ascription of single word labels; inferences are made about the target’s desires and intentions, trait-like tendencies, strategic motivations, and surrounding context ( Sander et al., 2007 ).

One approach to this issue is that of Scherer and colleagues, who propose that perceivers first infer specific appraisals in the expresser that prompted the expressive behavior in the first place ( Scherer & Grandjean, 2008 ). That is, if a person sees another person express anger in the face, or interest in the voice, or sympathy in a pattern of postural movement and tactile contact, the social perceiver first infers a pattern of appraisals that would lead the individual to express that particular emotion. From these inferred appraisals, the social perceiver, this line of theory maintains, then infers the experience of specific emotions. To illustrate, seeing someone express surprise in the face and voice might lead the observer to infer that the individual has been exposed to novel, unexpected information, which in turn would lead the observer to infer that the person is surprised. According to this account, the first inferences perceivers draw upon when seeing others’ expressive behavior is a pattern of appraisals, rather than distinct emotions.

In a similar spirit, Scarantino has synthesized studies of emotion perception in a theory of affective pragmatics ( Scarantino, 2017 ; Fischer & Sauter, 2017 ). He makes the case that emotional expressions - in the present case facial/bodily expressions -- communicate four kinds of information: 1) the individual’s current feeling (the expressive function of expression); 2) what is happening in the present context (the declarative function of expression); 3) desired courses of action from other people who perceive the expression (the imperative function of expression); and 4) intention and plans about what the person might do (the commissive function of expression).

As one empirical illustration of this thinking about the inferences that expressive behavior prompt, Shuman and colleagues presented observers with dynamic, videotaped portrayals of five different emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust ( Shuman et al., 2015 ). The expressions were dynamic, more realistic, and less exaggerated than those in the Ekman and Friesen photos, more like the expressions people see in everyday social interactions. In different response formats, participants matched each expression to either: feelings (“fear”), appraisals (“that is dangerous”), social relational meanings (“you scare me”), or action tendencies (“I might run”). Results showed that participants labeled the dynamic but subtle expressions with the expected response 62% of the time, with greater accuracy revealed when labeling expressions with feeling states, and reduced accuracy found in labeling action tendencies (see Hortsmann, 2003). More recent work in the Trobriand Islands found that action tendencies were more prominent in the interpretation of facial expressions than emotion words, suggesting possible cultural variations in the labeling of emotional expression ( Crivelli et al., 2016 ).

This emerging literature on the process of emotion recognition from expressive behavior, would be well served by taking on intriguing questions. Given what has been learned about the automaticity of inferring trust, warmth, and dominance from human faces (e.g., Oosterhof & Todorov, 2008 ), more fine-grained methods oriented toward unpacking the process of emotion recognition could yield insights into the primacy of what information is conveyed - feelings, appraisals, intentions - and the unfolding process of emotion perception.

The structure of emotion perception

Emotion perception involves more than labeling multimodal expressions with words that capture distinct emotions. The way that distinct emotional expressions relate to each other - that is, the structure of recognition - is also critically important. For instance, suppose a given study found that expressions of “love,” “joy,” and “embarrassment” were accurately identified in two cultures. If, in the same study, members of one culture thought the expression of “love” was similar in meaning to that of “joy” but not that of “embarrassment,” whereas in another culture individuals thought the expression of “love” was more similar in meaning to “embarrassment”, this would reveal a potentially important cultural difference in the emotional meaning attributed to the three expressions. The structure of the relatedness of meaning of the three expressions may, in fact, be as interesting as the fact that they can be differentiated in forced choice type labeling paradigms.

Consider this intriguing study on the structure of emotion perception by Rachael Jack and her colleagues ( Jack et al., 2012 ). These researchers relied on computer morphing technologies to generate over 2500 facial expressions based on the combined movements of anywhere from 1 to 6 Facial Action Units. They then presented these 2500 facial expressions as animations in sequences of four separate photos unfolding over 1.25 seconds, and had participants rate the emotional meaning of these expressions. With traditional factor analytic approaches, they documented that between 25 and 35 distinct states could be discerned in facial muscle movements, but that this realm of expression could be reduced to a simpler structure of four distinct patterns of Action Units well preserved in meaning across cultures. In both cultures, they distinguished (1) positive emotions, (2) sadness/fear-related emotions, (3) surprise-related emotions, and (4) disgust/anger-related emotions, respectively (for similar results on the variety of expressions see Cordaro et al., 2018 ; Du, Tao, & Martinez, 2014 ; for critique of study, see Sauter & Eisner, 2013 ).

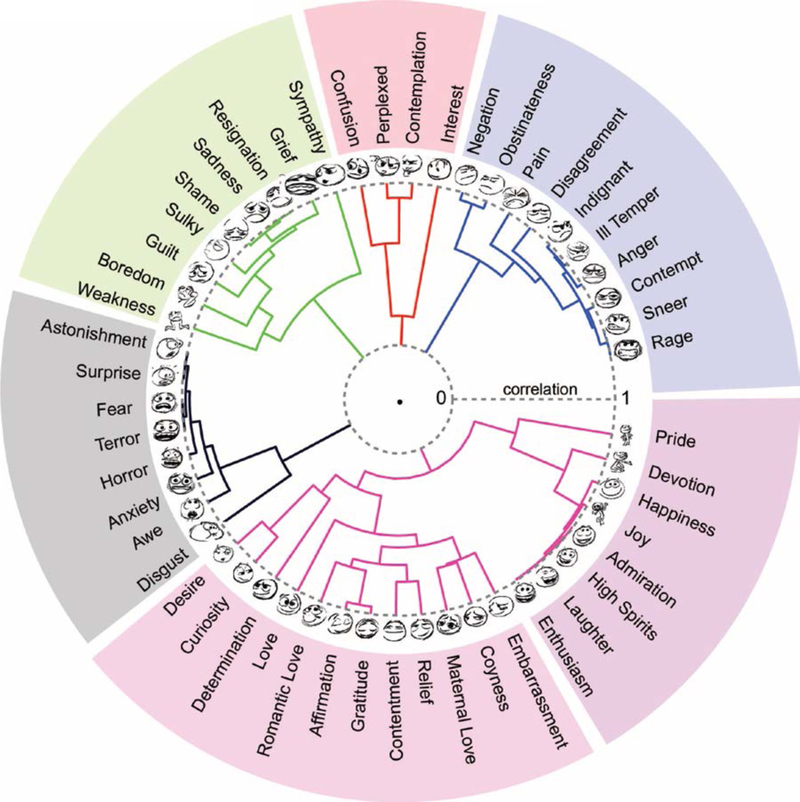

Another recent study took a different approach to examining cultural similarities and differences in the structure of emotion perception. Bai and colleagues ( Bai et al., 2018 ) began with more caricatured representations of 51 emotion concepts, created by asking a professional illustrator to draw each concept using emoji-like images. In one experiment, participants selfsorted the drawings, which were printed onto cards, into multiple stacks of drawings with similarity meaning. These data were processed with an agglomerative hierarchical clustering algorithm, resulting in tree-like representations of the structure of emotion perception, which correlated over .90 across the two cultures, and which we portray in Figure 2 .

A hierarchical taxonomy ofperception of 51 emoji-like drawings based on data from a card sorting study, averaging across US and Chinese participants.

Note. Leaves (outer edge of the hierarchy) correspond to individual drawings. These drawings are paired based on correlations in the proportion of matches with each other drawing. These pairings are then linked iteratively based on the average correlations between the judgment profiles of the two sets of drawings they contain, so as to maximize the correlations in judgments of the drawings that are grouped together. The correlation corresponding to each linkage is represented by its distance from the center, with the grey outer edge corresponding to a correlation of 1 and the inner circle corresponding to a correlation of 0. The branches of the tree are colored according to 5 top-level clusters linked at a correlation greater than 0. All linkages shown correspond to correlations that are significantly higher than would be expected if the linked branches were correlated only by chance, based on the number of leaves contained in each branch (p < .05).

As with the research by Rachel Jack and her colleagues, these approaches have the promise of capturing how expressions relate to one another, and broader categories of affective states that include distinct emotions.

The Contextual Shaping of Emotion Perception

A final growth area in the study of emotion perception is a focus on how emotion perception is shaped by features of the social context (Barrett et al., 2011; Hess & Hareli, 2017 ; Scherer, 1986 ). An important source of contextual shaping of emotion perception is, of course, culture. Cultures vary greatly in their prioritization and understanding of emotion concepts, knowledge, and representations, so culture will necessarily influence the perception of emotion in expression. For example, cultures vary in their attention to the surrounding context of an expression. In one paradigmatic experiment, Masuda and colleagues showed Japanese and American participants cartoon figures with various facial expressions ( Masuda, Ellsworth, Mesquita, Leu, & van de Veerdonk, 2004 ). The central, target face was always surrounded by smaller, less salient faces, that displayed expressions that were dissimilar to those of the target. Japanese participants’ judgments about the central target’s facial expression were more influenced by the surrounding faces than were judgments made by Americans -who tended to restrict their focus to the expression shown by the central target. Differences between groups of perceivers have also been found for populations that differ on other dimensions than culture, such as social class. In this vein, Kraus and colleagues have found that lower class individuals - more oriented to the social context than upper class individuals - also incorporate contextual information into their judgments of expressive behavior to a greater extent ( Kraus et al., 2010 ).

A second source of variation is situational - who is the person expressing emotion, and what context are they in? How might the gender, power, ethnicity or social class of the individual expressing emotion shape what emotion observers perceive? For example, people are more likely to detect anger in men’s expressions of emotion, but sadness in expressions of women ( Hess & Hareli, 2017 ). US participants are more likely to perceive anger in the emotional expressions of African Americans (Hugenberg & Bodenhausen, 2003). Also relevant are what other behaviors expressers might be engaging in. For example, Aviezer and colleagues (2008) presented a photograph of a prototypical facial expression of disgust in one of four stimulus contexts, with the person expressing disgust engaged in different actions. Participants labeled the expression as disgust 91% of the time when the individual was holding a soiled article of clothing, 59% of the time when the person displayed fearful hand and arm movements, 33% of the time when the same person was clasping his or her hands sadly to the chest, and 11% of the time when the person was poised with fists clenched to punch. These results suggest that people do not see and perceive faces in a vacuum; rather, they are one very important predictor of emotion perceptions, which are used in combination with other contextual information to form judgments. Recent findings also highlight that a person’s previous emotional expressions can influence how a current emotional expression is perceived (Fang, Sauter & van Kleef, 2017). Clearly, the many dimensions of context - the nature of the expresser, the surrounding people, the formality or informality of the setting - all influence emotion perception.

A third kind of context is perceptual context (Barrett et al., 2011). Perceptual context refers to the mental states within the perceiver’s mind that shape his or her inferences upon observing expressive behavior. A person’s current feelings, goals, intentions, values, and physical state give rise to context-specific interpretations of social expressive behavior. For example, recent studies find that the likelihood that participants will label a disgust expression as “disgust” rises when an anger expression precedes the presentation of the disgust expression, but drops when no anger expression precedes the target disgust expression (Pochedly, Widen, & Russell, 2012).

Emotional Expression and the Coordination of Social Interaction

Based on his years of intensive observation of pre-industrial peoples, Irenaus Eibl- Eibesfeldt posited that emotional expressions are the “grammar of social interaction” (1989). Facial expressions, vocalizations, patterns of bodily movement, gaze, gestures, and touch bind people into dyadic and group-based interactions—the soothing of a distressed child, flirtation between potential suitors, sexual interaction, the play of young siblings, the aggressive encounters of rivals, or status conflicts in groups.

A corollary to this analysis is that emotional expressions trigger systematic inferences and behavioral responses in others. This thinking requires that we shift a level of analysis, and look from individuals’ expressions of emotion to the dyadic and group level (Tiedens & Leach, 2004; Keltner & Haidt, 1999), as has been done in the study of emotional mimicry ( Hess & Fischer, 2013 ). In other words, perceivers do not merely recognize emotions from nonverbal displays - they also respond to them with their own emotion-guided behaviors, ranging from mimicry, coordination, and tenderness to antagonism and avoidance.

Consider the recent theorizing of Paula Niedenthal and her colleagues concerning how different smiles and laughs evoke different inferences and responses in others ( Niedenthal et al., 2010 ). Within 500 milliseconds, this theorizing posits, people respond to smiles with mimetic behavior and physiological reactions. For example, a warm smile of enjoyment triggers neural processes that lead the perceiver to seek more information about the smiler through eye contact, which in turn evokes feelings of pleasure, mimetic behavior, and the experience of positive emotion and approach behavior. A proud, dominant smile, by contrast, triggers the same automatic search for information about the smiler, along with neural activation that leads to a sense of threat and avoidant behavior.

So how do emotional expressions coordinate social interactions? Three ideas have emerged ( Keltner & Kring, 1998 ; Niedenthal & Brauer, 2011; van Kleef, 2009 ). A first is that emotional expressions rapidly provide important information relevant to perceivers, useful in guiding subsequent behavior. For example, emotional expressions can signal trait-like tendencies of individuals. Individuals looking angry are perceived as dominant (Knutson, 1996) and those showing embarrassment are seen as being of upstanding character (Feinberg et al.,2012). Pride displays promote automatic, cross-cultural judgments of high status in the displayer—judgments that are strong enough to counter contextual information indicating that the displayer in fact merits low status ( Shariff & Tracy, 2009 ; Shariff, Tracy, & Markusoff, 2012 ; Tracy, Shariff, Zhao, & Henrich, 2013 ).

Emotional expressions also signal the trustworthiness of the sender ( Fang, van Kleef & Sauter, in press ). In one study, Krumhuber and colleagues found that people trust interaction partners more, and will give more resources to those partners, if the partners display authentic smiles (which have longer onset and offset times) compared to fake smiles, which have shorter onset and offset (Krumhuber et al., 2013). Social perceivers also infer trustworthy intentions from people who spontaneously display intense embarrassment, and are more likely to cooperate with individuals who express embarrassment than other emotions (Feinberg et al., 2012). Pride displays direct social learning by providing information to others; individuals motivated to attain the correct answer to a difficult trivia question were found to selectively copy the answer provided by others showing pride, more so than others showing happiness or a neutral display, suggesting that pride displays communicate expertise or knowledge (Martens & Tracy, 2013).

Emotional expressions also convey essential information about the environment (e.g., Klinnert et al., 1986; Sorce et al., 1985). For example, parents use touch and voice to signal to their young children as to whether other people and objects in the environment are safe or dangerous (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004), using vocal cues that are consistent across cultures (Bryant & Barrett, 2007).

Emotional displays coordinate social interactions in a second way, by evoking specific responses in social perceivers. Early studies in this tradition found that some emotional expressions trigger complementary emotions in social perceivers: facial displays of anger enhance fear conditioning in observers, even when the anger displays are not consciously perceived (Ohman & Dimberg, 1978); expressions of distress can evoke sympathy in observers (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1989 ); displays of dominance trigger more submissive expressive behavior (Tiedens & Fragale, 2003). More recently, van Dijk and colleagues ( van Dijk et al., 2009 ) have documented that the blush is an involuntary, costly way in which people signal their awareness and regret for the mistake they have made: social observers responded with more positive emotion to individuals who blushed after they made mistakes than if they showed other display behavior.

Finally, emotional expressions structure social interactions by serving as incentives for others’ actions, by rewarding specific patterns of behavior in perceivers. Early studies on this notion focused on how parents use warm smiles and touches to increase the likelihood of certain behaviors in their children (e.g., Tronick, 1989 ) and the incentive value of laughter, and how it triggers cooperative interactions between friends ( Owren & Bachorowski, 2001 ).

This analysis of the rewarding properties of emotional expression likewise sheds light on some of the direct effects of emotional touch upon recipients of touch (for review, see Keltner, 2009 ). Gentle, pleasing touch triggers activation in the orbitofrontal cortex, a brain region involved in the representation of secondary rewards. Given the rewarding quality of being touched, it has been claimed that touch motivates sharing behavior in others ( De Waal, 1996 ). This may help explain why warm touch increases compliance to requests (Willis & Hamm, 1980) and cooperation toward strangers in economic games.

Clearly, the study of how expressions coordinate social interactions are in their infancy. Many of the studies of the informative, evocative, and incentive functions of expressions have largely focused on the face; it will be important to extend this line of reasoning to studies of the voice, touch, gaze, and other modalities. With a few exceptions, this work has focused on a fairly limited set of emotional displays - smiles, anger displays, disgust expressions, and fear expressions. It will be important to examine how less studied expressions of emotion, for example of interest (in the voice), gratitude (in touch), sympathy (in the voice or touch), or awe (in the voice), coordinate social interactions.

Studies of the social functions of emotional expressions have set the stage for new theorizing. One recent line of argument has outlined how emotional expressions evolved to serve these informative, evocative, and incentive signaling functions, perhaps in the “second stage” of their evolution (see Shariff & Tracy, 2011 ). This account dates back to Darwin (1872) , and argues that internal physiological regulation was likely the original adaptive function of emotion expressions, which later evolved to serve communicative functions (e.g., Chapman, Kim, Susskind & Anderson, 2009; Eibl-Eibsfeldt, 1989 ; Ekman, 1992 ; Shariff & Tracy, 2011 ).

To take the classic example of fear, the facial muscle movements that constitute a fear expression likely originally emerged as part of a functional response to threatening stimuli; widened eyes increase the scope of one’s visual field and the speed of eye movements, allowing expressers to better identify (potentially threatening) objects in their periphery (Susskind et al.,2008). In contrast, the ‘scrunched’ nose and mouth of the disgust expression results in constriction of these orifices, thereby reducing air intake (Chapman, Kim, Susskind & Anderson, 2009). Given that disgust functions to alert expressers of the potentially noxious nature of the eliciting stimulus, and thereby disincline them from ingesting it (Rozin, Lowery, & Ebert, 1994), the reduced inhalation of airborne chemicals can well be considered part of the same adaptive response. In more recent work, these authors have shown that the opposing eye movements involved in fear and disgust expressions (i.e., widening versus narrowing) function to increase visual sensitivity (localizing an object) and acuity (determining what the object is), respectively—further supporting the argument that these two expressions initially evolved to serve opposing yet equally important functions for the expresser ( Lee, Susskind, & Anderson, 2013 ).

However, many of these original physiological benefits experienced by expressers eventually became transformed into communicative signals, which benefit both expressers and observers by virtue of allowing for more efficient communication and coordinated interactions. Over time, the facial and bodily behavioral components of certain emotions came to signal those emotional states to observers, through processes of ritualization, wherein mammalian nonverbal displays become exaggerated, more visible, distinctive and/or prototypic, and ultimately, more recognizable ( Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989 ; Shariff & Tracy, 2011 ).

Looking forward to future advances in the study of emotional expression

In this review, we have summarized recent advances in the study of emotional expression inspired by Basic Emotion Theory. This literature reveals that there are upwards of 20 emotions with distinct, multimodal expressions. Intriguing discoveries highlight how this increasingly rich array of states with multimodal expressions might have a deeper structure that speaks to the potential evolutionary origins of emotional expression. And work is revealing how emotional expressions coordinate social interactions; they are indeed a grammar of social living.

These advances in the study of emotional expression are already proving to be generative in advancing other core hypotheses of Basic Emotions Theory. As one example, within this theoretical framework it is assumed that emotions involve emotion-specific physiology, which enable specific behaviors in response to eliciting stimuli - flight, skin-to-skin contact, the widening of the eyes to take in more information, clasping and striking. The literature we have reviewed here has begun to illuminate how distinct emotions covary with distinct physiological response. For example, brief nonverbal displays of love (Duchenne smile, head tilt, open handed gestures) correlate with oxytocin release, whereas cues of sexual desire (lip licks, lip puckers) do not ( Gonzaga et al., 2006 ). Sympathy-related oblique eyebrow movements relate to increased activation in the vagus nerve, a branch of the parasympathetic autonomic nervous system that supports care-giving in mammals ( Eisenberg et al., 1989 ; Stellar, Cohen, Oveis, & Keltner, 2015 ). Recent work finds that fear-related vocalizations, but not those of other emotions, covary with cortisol release ( Anderson et al., 2018 ). This work suggests that more precise measurement of emotional expression may yield new insights into emotion-related physiology.

Critical to Basic Emotions Theory is the notion that human emotional expression arose during the process of mammalian evolution, and, by implication, that there should be compelling homologies between human and non-human behavior. Careful cross-species comparisons between human and nonhuman expressive behavior have revealed functional origins of laughter, smiling, embarrassment, affiliative cues involved in love, sexual signaling, threat displays, and dominance (for review see Keltner et al., 2016 ). Careful analyses of nonhuman vocal displays find distinct displays for sex, food, affiliation, care-giving, and threat (e.g., Briefer, 2012 ; Morton, 1977 ; Snowdon, 2003 ).

In moving beyond the basic six, new studies of emotional expression guided by Basic Emotion Theory are generating important advances in understanding what emotions are, and how they shape human social life.

Contributor Information

Dacher Keltner, University of California, Berkeley.

Disa Sauter, Amsterdam University.

Jessica Tracy, University of British Columbia.

Alan Cowen, University of California, Berkeley.

- Anderson CL, Moroy M, & Keltner D (2018). Emotion in the wilds of nature: The coherence and contagion of fear during threatening group-based outdoors experiences. Emotion, 18(3), 355–368. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- App B, McIntosh DN, Reed CL & Hertenstein MJ (2011). Nonverbal channel use in communication of emotion: How may depend on why. Emotion, 11(3), 603–617. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aviezer H, Trope Y, & Todorov A (2012). Body cues, not facial expressions, discriminate between intense positive and negative emotions. Science, 338(6111), 1225–1229. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bai Y, McNeil G, Cowen A, & Keltner D (2018). Darwin’s Emoji: Dimensionality, structure, and conceptualization in the recognition of emotion. Manuscript under review. [ Google Scholar ]

- Balsters MJH, Krahmer EJ, Swerts MGJ & Vingerhoets AJJM (2013). Emotional tears facilitate the recognition of sadness and the perceived need for social support. Evolutionary Psychology, 11(1), 148–158. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Banse R, & Scherer KR (1996). Acoustic profiles in vocal emotion expression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 614. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrett LF, Lindquist KA, & Gendron M (2007). Language as context for the perception of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(8), 327–332. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Botvinick M, Jha AP, Bylsma LM, Fabian SA, Solomon PE, & Prkachin KM (2005). Viewing facial expressions of pain engages cortical areas involved in the direct experience of pain. Neuroimage, 25(1, 312–319. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Briefer EF (2012). Vocal expression of emotions in mammals: mechanisms of production and evidence. Journal of Zoology, 288(1), 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Campos B, Shiota M, Keltner D, Gonzaga G, & Goetz J (2013). What is shared, what is different? Core relational themes and expressive displays of eight positive emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 27,37–52. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cordaro DT (2013). Universals and cultural variations in expression in five cultures. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cordaro DT, Keltner D, Tshering S, Wangchuk D, & Flynn L (2016). The voice conveys emotion in ten globalized cultures and one remote village in Bhutan. Emotion, 1, 117–128. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cordaro DT, Sun R, Keltner D, Kamble S Huddar N., & McNeil G. (2018). Universals and cultural variations in 22 emotional expressions across five cultures. Emotion, 18 (1), 75–93. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crivelli C, Jarillo S, Russell JA, & Fernandez-Dols JM (2016). Reading emotions from faces in two indigenous societies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145, 830–843. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crivelli C, Russell JA, Jarillo S, & Fernandez-Dols JM (2016). The fear gasping face as a threat display in a Melanesian society. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(44), 12403–12407. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dael N, Mortillaro M, & Scherer KR (2012). Emotion expression in body action and posture. Emotion, 12(5), 1085. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Darwin C (1872/1998). The expression of the emotions in man and animals (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Waal FB (1996). Goodnatured. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Du S, Tao Y, & Martinez AM (2014). Compound facial expressions of emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(15), E1454–E1462. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dubois A, Bringuier S, Capdevilla X, & Pry R (2008). Vocal and verbal expression of postoperative pain in preschoolers. Pain Management Nursing, 9(4), 160–165. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duran JI, Reisenzein R, & Fernandez-Dols J-M (2017). Coherence between emotions and facial expressions In Fernandez-Dols J-M & Russell JA (Eds). The Science of Facial Expression (pp. 107–129). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eibl-Eibesfeldt I (1989). Human Ethology. New York: Aldine De Gruyter. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Miller PA, Fultz J, Shell R, Mathy RM, & Reno RR (1989). Relation of sympathy and personal distress to prosocial behavior: A multimethod study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(1), 55. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 169–200. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P (1993). Facial Expression of Emotion. American Psychologist, 48, 384–392. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman PE, & Davidson RJ (1994). The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions. Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P, & Rosenberg EL (Eds.). (1997). What the face reveals: Basic and applied studies of spontaneous expression using the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P, & Friesen WV (1986). A new pan-cultural facial expression of emotion. Motivation and Emotion, 10(2), 159–168. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P, & Friesen WV (1978). Facial Action Coding System: Investigatoris Guide. Consulting Psychologists Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P, & Cordaro D (2011). What is meant by calling emotions basic. Emotion Review, 3(4), 364–370. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ekman P, Sorenson ER, & Friesen WV (1969). Pan-cultural elements in the Facial Display of Emotions. Science, 164, 86–88. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elfenbein HA (2013). Nonverbal dialects and accents in facial expressions of emotion. Emotion Review, 5(1), 90–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elfenbein HA, Ambady N (2002) On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion regulation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 203–235. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fang X, Sauter DA, & van Kleef G (2018). Mixed emotions: The specificity of emotion perception from static and dynamic faces across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(1), 130–148. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fang X, van Kleef G & Sauter DA (in press). Person Perception from Changing Emotional Expressions: Primacy, Recency, or Averaging Effect? Cognition and Emotion. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fischer AH, & Sauter DA (2017). What the Theory of Affective Pragmatics Does and Doesn't Do. Psychological Inquiry, 28(2–3), 190–193. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flack W (2006). Peripheral feedback effects of facial expressions, bodily postures, and vocal expressions on emotional feelings. Cognition & Emotion, 20(2), 177–195. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fridlund AJ (1991). Evolution and facial action in reflex, social motive, and paralanguage. Biological Psychology, 32(1), 3–100. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frijda NH (1986). The Emotions. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goetz JL, Keltner D & Simon-Thomas E (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gonzaga GC, Turner RA, Keltner D, Campos B, & Altemus M (2006). Romantic love and sexual desire in close relationships. Emotion, 6(2), 163–179. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gross MM, Crane EA, & Fredrickson BL (2010). Methodology for assessing bodily expression of emotion. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34(4), 223–248. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grunau RV, & Craig KD (1987). Pain expression in neonates: facial action and cry. Pain, 28(3), 395–410. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haidt J, & Keltner D (1999). Culture and facial expression: Open-ended methods find more faces and a gradient of recognition. Cognition & Emotion, 13, 225–266. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hawk ST, Kleef GAV, Fischer AH, & Schalk JVD (2009). “Worth a thousand words”: Absolute and relative decoding of nonlinguistic affect vocalizations. Emotion, 9, 293–305. doi: 10.1037/a0015178 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hejmadi A, Davidson RJ, & Rozin P (2000). Exploring Hindu Indian emotion expressions: Evidence for accurate recognition by Americans and Indians. Psychological Science, 11(3), 183–187. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hertenstein MJ, Holmes R, McCullough M, & Keltner D (2009). The communication of emotion via touch. Emotion, 9(4), 566–573. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hertenstein MJ, Keltner D, App B, Bulleit BA, & Jaskolka AR (2006). Touch communicates distinct emotions. Emotion, 6(3), 528–533. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess U, & Fischer A (2013). Emotional mimicry as social regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 142–157. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess. U, & Hareli S (2017). The social signal value of emotions: The role of contextual factors in social inferences from emotional displays In Russell J & Fernandez-Dols J-M (Eds.), The Psychology of Facial Expression (pp. 375–392). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Horstmann G (2003). What do facial expressions convey: Feeling states, behavioral intentions, or actions requests? Emotion, 3(2), 150–166. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jack RE, Garrod OG, Yu H, Caldara R, & Schyns PG (2012). Facial expressions of emotion are not culturally universal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(19), 7241–7244. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Juslin PN, & Laukka P (2003). Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code?. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 770–814. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D (2009). Born to be good: The science of a meaningful life. New York: WW Norton & Company. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D (1995). Signs of appeasement: Evidence for the distinct displays of embarrassment, amusement, and shame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3), 441–454. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D (1996). Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 10(2), 155–172. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D, & Bonanno GA (1997). A study of laughter and dissociation: Distinct correlates of laughter and smiling during bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(4), 687. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D, & Cordaro DT (2016). Understanding multimodal emotional expressions: Recent advances in Basic Emotion Theory. Emotion Researcher, Andrea Scarantino (ed.). http://emotionresearcher.com/ [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D, & Haidt J (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D & Kring AM (1998). Emotion, social function, and psychopathology. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 320–342. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D & Lerner J (2010). Emotion In Fiske Giblert and Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology, Volume 1 (pp. 317–342). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D, & Shiota MN (2003). New displays and new emotions: A commentary on Rozin and Cohen (2003). Emotion, 3(1), 86–91. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D, & Buswell BN (1997). Embarrassment: Its distinct form and appeasement functions. Psychological Bulletin, 122(3), 250–264. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D, Sauter D, Tracy J, McNeil G, & Cordaro DT (2016). Expression. In Barrett LF, Lewis M, & Haviland-Jones J (Ed.), Handbook of emotion. (pp. 467–482). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keltner D, & Haidt JA (2001). Social functions of emotions In Mayne T & Bonanno G, (Eds.), Emotions:Current Issues and future directions. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraus MW, Côté S, & Keltner D (2010). Social class, contextualism, and empathie accuracy. Psychological Science, 21, 1716–1723. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laukka P, Elfenbein HA, Söder N, Nordstrom H, Althoff J, Chui W, et al. (2013). Cross-cultural decoding of positive and negative non-linguistic emotion vocalizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 353: doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00353 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laukka P, Elfenbein HA, Thingujam NS, Rockstuhl T, Iraki F, Wanda C, & Althoff J (2016). The expression and recognition of emotions in the voice across five nations: A lens model analysis based on acoustic features. Journal of Personaity and Social Psychology, 11 (5), 686–705. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee DH, Susskind JM, & Anderson AK (2013). Social transmission of the sensory benefits of eye widening in fear expressions. Psychological Science, 24(6), 957–965. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lench HC, Flores SA, & Bench SW (2011). Discrete emotions predict changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology: A meta-analysis of experimental emotion elicitations. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 834–855. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levenson RW, Ekman P, & Friesen WV (1990). Voluntary facial action generates emotion-specific autonomic nervous system activity. Psychophysiology, 27(4), 363–384. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maruskin LA, Thrash TM, & Elliot AJ (2012). The chills as a psychological construct: Content universe, factor structure, affective composition, elicitors, trait antecedents, and consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 135–157. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Masuda T, Ellsworth PC, Mesquita B, Leu J, & van de Veerdonk E (2004). A face in the crowd or a crowd in the face: Japanese and American perceptions of others’ emotions. Unpublished manuscript, Hokkaido University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matsumoto D, et al. (2008). Facial expressions of emotion In Lewis Haviland-Jones & Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of Emotions, Third Edition (pp. 211–234). New York: The Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matsumoto D, & Hwang HC (2017). Methodological issues regarding cross-cultural studies of judgments of facial expressions. Emotion Review, 9(4), 375–382. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morton ES (1977). On the occurrence and significance of motivation-structural rules in some bird and mammal sounds. American Naturalist, 111, 855–869. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson NL, & Russell JA (2013). Universality revisited. Emotion Review, 5(1), 8–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- Niedenthal PM, Mermillod M, Maringer M, & Hess U (2010). The Simulation of Smiles (SIMS) model: Embodied simulation and the meaning of facial expression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(06), 417–433. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nummenmaa L, & Saarimäki H (2017). Emotions as discrete patterns of systemic activity. Neuroscience letters. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oatley K (2004). Scripts, transformations, and suggestiveness, of emotions in Shakespeare and Chekhov. Review of General Psychology, 8, 323–340. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oosterhof NN, & Todorov A (2008). The functional basis of face evaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 105, 11087–11092. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ortony A, & Turner TJ (1990). What's basic about basic emotions?. Psychological Review, 97(3), 315. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oveis C, Horberg EJ, & Keltner D (2010). Compassion, pride, and social intuitions of self-other similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,.98(4), 618. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Owren MJ, & Bachorowski J (2001). The evolution of emotional expression: A “selfish-gene” account of smiling and laughter in early hominids and humans In Mayne TJ & Bonanno GA (Eds.), Emotions: Current issues and future directions (pp. 152–191). New York, NY: Guilford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parkinson B (2005). Do facial movements express emotion or communicate social motives? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9, 278–311. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pell MD, Monetta L, Paulmann S & Kots SA (2009). Recognizing emotions in a foreign language. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 33, 107–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Piff PK, Purcell A, Gruber J, Hertenstein MJ, & Keltner D (2012). Contact high: Mania proneness and positive perception of emotional touches. Cognition & Emotion, 26(6), 1116–1123. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prkachin KM (1992). The consistency of facial expressions of pain: A comparison across modalities. Pain, 51(3), 297–306. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reddy V (2000). Coyness in early infancy. Developmental Science, 3(2), 186–192. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reddy V (2005). Feeling shy and showing-off: Self-conscious emotions must regulate selfawareness. Emotional Development, 183–204. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reeve J (1993). The face of interest. Motivation and Emotion, 17(4), 353–375. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rozin P, & Cohen AB (2003). High frequency of facial expressions corresponding to confusion, concentration, and worry in an analysis of naturally occurring facial expressions of Americans. Emotion, 3(1), 68–75. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell JA (1994). Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expressions? A review of the cross-cultural studies. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 102–141. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sander D, Grandjean D, Kaiser S, Wehrle T, & Scherer KR (2007). Interaction effects of perceived gaze direction and dynamic facial expression: Evidence for appraisal theories of emotion. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(3), 470–480. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sauter DA, & Eisner F (2013). Commonalities outweigh differences in the communication of emotions across human cultures [Letter to the editor]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110 (3), E180. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sauter DA, & Scott SK (2007). More than one kind of happiness: Can we recognize vocal expressions of different positive states? Motivation and Emotion, 31(3), 192–199. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sauter DA, Eisner F, Calder AJ & Scott SK (2010). Perceptual cues in non-verbal vocal expressions of emotion. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63(11), 2251–2272. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sauter DA, Eisner F, Ekman P, & Scott SK (2010). Cross-cultural recognition of basic emotions through nonverbal emotional vocalizations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(6), 2408–2412. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sauter DA, Eisner F, Ekman P, & Scott SK (2015). Emotional vocalisations are recognised across cultures regardless of distractor valence. Psychological Science, 26(3), 354–356. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sauter DA, Panattoni C, & Happe F (2013). Children’s recognition of emotions from vocal cues. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 97–113. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sauter DA, Gangi D, McDonald N, & Messinger DS (2014). Nonverbal expressions of positive emotions In Shiota MN, Tugade MM, and Kirby LD (Eds.) Handbook of Positive Emotion (pp 179–200). New York: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Scarantino A (2017). How to Do Things with Emotional Expressions: The Theory of Affective Pragmatics, Psychological Inquiry, 28:2–3, 165–185 [ Google Scholar ]

- Scherer KR (1986). Vocal affect expression: A review and a model for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 99 (2), 43–65. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scherer KR, & Ellgring H (2007). Multimodal expression of emotion: Affect programs or componential appraisal patterns?. Emotion, 7(1), 113–130. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scherer KR, & Grandjean D (2008). Facial expressions allow inference of both emotions and their components. Cognition and Emotion, 22(5), 789–801. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schröder M (2003). Experimental study of affect bursts. Speech Communication, 40(1), 99–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shariff AF, & Tracy JL (2011). What are emotion expressions for?. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(6), 395–399. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shariff AF, & Tracy JL (2009). Knowing who’s boss: Implicit perceptions of status from the nonverbal expression of pride. Emotion, 9, 631–639. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shariff AF, Tracy JL, & Markusoff J (2012). (Implicitly) judging a book by its cover: The power of pride and shame expressions in shaping judgments of social status. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 1178–1193. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shiota MN, Campos B, & Keltner D (2003). The faces of positive emotion: prototype displays of awe, amusement, and pride. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1000, 296. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shiota MN, Keltner D, & Mossman A (2007). The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition & Emotion, 21(5), 944–963. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shiota MN, Campos B, Oveis C, Hertenstein M, Simon-Thomas E, & Keltner D (2017). Beyond happiness: Toward a science of discrete positive emotions. American Psychologist, 72 (7), 617–643. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shuman V, Clark-Polner E Meuleman B, Sander D, & Scherer KR. (2015). Emotion perception from a componential perspective. Cognition & Emotion, 37 (1), 47–56. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Silvia PJ (2008). Interest—The curious emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(1), 57–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- Simon-Thomas ER, Keltner DJ, Sauter D, Sinicropi-Yao L, & Abramson A (2009). The voice conveys specific emotions: Evidence from vocal burst displays. Emotion, 9(6), 838. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snowdon CT (2003). Expression of Emotion in Nonhuman Animals. In Davidson Scherer & Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of Affective Sciences (pp. 457–534). New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stellar JE, Cohen A, Oveis C, & Keltner D (2015, January 26). Affective and Physiological Responses to the Suffering of Others: Compassion and Vagal Activity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 572–585. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Szameitat DP, Alter K, Szameitat AJ, Darwin CJ, Wildgruber D, Dietrich S, & Sterr A (2009). Differentiation of Emotions in Laughter at the Behavioral Level. Emotion, 9(3), 397–405. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tracy JL, & Robins RW (2004). Show your pride evidence for a discrete emotion expression. Psychological Science, 15(3), 194–197. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tracy JL, & Robins RW (2008). The nonverbal expression of pride: Evidence for cross-cultural recognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 516–530. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tracy JL, & Robins RW (2007). The prototypical pride expression: Development of a nonverbal behavioral coding system. Emotion, 7, 789–801. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tracy JL, Robins RW, & Schriber RA (2009). Development of a FACS-verified set of basic and self-conscious emotion expressions. Emotion, 9, 554–559. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tracy JL & Matsumoto D (2008). The spontaneous expression of pride and shame: Evidence for biologically innate nonverbal displays. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(33), 11655–11660. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]