An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Types of Study in Medical Research

Part 3 of a Series on Evaluation of Scientific Publications

Bernd Röhrig , Dr. rer. nat.

Jean-baptist du prel , dr. med., daniel wachtlin, maria blettner , prof. dr. rer. nat..

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*MDK Rheinland-Pfalz, Referat Rehabilitation/Biometrie, Albiger Str. 19 d, 55232 Alzey, Germany, [email protected]

Received 2008 Jun 30; Accepted 2008 Nov 13; Issue date 2009 Apr.

The choice of study type is an important aspect of the design of medical studies. The study design and consequent study type are major determinants of a study’s scientific quality and clinical value.

This article describes the structured classification of studies into two types, primary and secondary, as well as a further subclassification of studies of primary type. This is done on the basis of a selective literature search concerning study types in medical research, in addition to the authors’ own experience.

Three main areas of medical research can be distinguished by study type: basic (experimental), clinical, and epidemiological research. Furthermore, clinical and epidemiological studies can be further subclassified as either interventional or noninterventional.

Conclusions

The study type that can best answer the particular research question at hand must be determined not only on a purely scientific basis, but also in view of the available financial resources, staffing, and practical feasibility (organization, medical prerequisites, number of patients, etc.).

Keywords: study type, basic research, clinical research, epidemiology, literature search

The quality, reliability and possibility of publishing a study are decisively influenced by the selection of a proper study design. The study type is a component of the study design (see the article "Study Design in Medical Research") and must be specified before the study starts. The study type is determined by the question to be answered and decides how useful a scientific study is and how well it can be interpreted. If the wrong study type has been selected, this cannot be rectified once the study has started.

After an earlier publication dealing with aspects of study design, the present article deals with study types in primary and secondary research. The article focuses on study types in primary research. A special article will be devoted to study types in secondary research, such as meta-analyses and reviews. This article covers the classification of individual study types. The conception, implementation, advantages, disadvantages and possibilities of using the different study types are illustrated by examples. The article is based on a selective literature research on study types in medical research, as well as the authors’ own experience.

Classification of study types

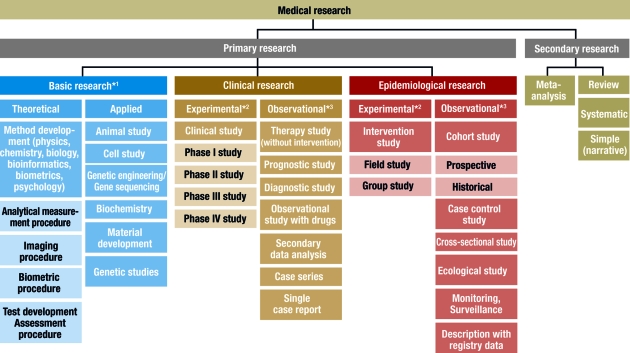

In principle, medical research is classified into primary and secondary research. While secondary research summarizes available studies in the form of reviews and meta-analyses, the actual studies are performed in primary research. Three main areas are distinguished: basic medical research, clinical research, and epidemiological research. In individual cases, it may be difficult to classify individual studies to one of these three main categories or to the subcategories. In the interests of clarity and to avoid excessive length, the authors will dispense with discussing special areas of research, such as health services research, quality assurance, or clinical epidemiology. Figure 1 gives an overview of the different study types in medical research.

Classification of different study types

*1 , sometimes known as experimental research; *2 , analogous term: interventional; *3 , analogous term: noninterventional or nonexperimental

This scheme is intended to classify the study types as clearly as possible. In the interests of clarity, we have excluded clinical epidemiology — a subject which borders on both clinical and epidemiological research ( 3 ). The study types in this area can be found under clinical research and epidemiology.

Basic research

Basic medical research (otherwise known as experimental research) includes animal experiments, cell studies, biochemical, genetic and physiological investigations, and studies on the properties of drugs and materials. In almost all experiments, at least one independent variable is varied and the effects on the dependent variable are investigated. The procedure and the experimental design can be precisely specified and implemented ( 1 ). For example, the population, number of groups, case numbers, treatments and dosages can be exactly specified. It is also important that confounding factors should be specifically controlled or reduced. In experiments, specific hypotheses are investigated and causal statements are made. High internal validity (= unambiguity) is achieved by setting up standardized experimental conditions, with low variability in the units of observation (for example, cells, animals or materials). External validity is a more difficult issue. Laboratory conditions cannot always be directly transferred to normal clinical practice and processes in isolated cells or in animals are not equivalent to those in man (= generalizability) ( 2 ).

Basic research also includes the development and improvement of analytical procedures—such as analytical determination of enzymes, markers or genes—, imaging procedures—such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging—, and gene sequencing—such as the link between eye color and specific gene sequences. The development of biometric procedures—such as statistical test procedures, modeling and statistical evaluation strategies—also belongs here.

Clinical studies

Clinical studies include both interventional (or experimental) studies and noninterventional (or observational) studies. A clinical drug study is an interventional clinical study, defined according to §4 Paragraph 23 of the Medicines Act [Arzneimittelgesetz; AMG] as "any study performed on man with the purpose of studying or demonstrating the clinical or pharmacological effects of drugs, to establish side effects, or to investigate absorption, distribution, metabolism or elimination, with the aim of providing clear evidence of the efficacy or safety of the drug."

Interventional studies also include studies on medical devices and studies in which surgical, physical or psychotherapeutic procedures are examined. In contrast to clinical studies, §4 Paragraph 23 of the AMG describes noninterventional studies as follows: "A noninterventional study is a study in the context of which knowledge from the treatment of persons with drugs in accordance with the instructions for use specified in their registration is analyzed using epidemiological methods. The diagnosis, treatment and monitoring are not performed according to a previously specified study protocol, but exclusively according to medical practice."

The aim of an interventional clinical study is to compare treatment procedures within a patient population, which should exhibit as few as possible internal differences, apart from the treatment ( 4 , e1 ). This is to be achieved by appropriate measures, particularly by random allocation of the patients to the groups, thus avoiding bias in the result. Possible therapies include a drug, an operation, the therapeutic use of a medical device such as a stent, or physiotherapy, acupuncture, psychosocial intervention, rehabilitation measures, training or diet. Vaccine studies also count as interventional studies in Germany and are performed as clinical studies according to the AMG.

Interventional clinical studies are subject to a variety of legal and ethical requirements, including the Medicines Act and the Law on Medical Devices. Studies with medical devices must be registered by the responsible authorities, who must also approve studies with drugs. Drug studies also require a favorable ruling from the responsible ethics committee. A study must be performed in accordance with the binding rules of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) ( 5 , e2 – e4 ). For clinical studies on persons capable of giving consent, it is absolutely essential that the patient should sign a declaration of consent (informed consent) ( e2 ). A control group is included in most clinical studies. This group receives another treatment regimen and/or placebo—a therapy without substantial efficacy. The selection of the control group must not only be ethically defensible, but also be suitable for answering the most important questions in the study ( e5 ).

Clinical studies should ideally include randomization, in which the patients are allocated by chance to the therapy arms. This procedure is performed with random numbers or computer algorithms ( 6 – 8 ). Randomization ensures that the patients will be allocated to the different groups in a balanced manner and that possible confounding factors—such as risk factors, comorbidities and genetic variabilities—will be distributed by chance between the groups (structural equivalence) ( 9 , 10 ). Randomization is intended to maximize homogeneity between the groups and prevent, for example, a specific therapy being reserved for patients with a particularly favorable prognosis (such as young patients in good physical condition) ( 11 ).

Blinding is another suitable method to avoid bias. A distinction is made between single and double blinding. With single blinding, the patient is unaware which treatment he is receiving, while, with double blinding, neither the patient nor the investigator knows which treatment is planned. Blinding the patient and investigator excludes possible subjective (even subconscious) influences on the evaluation of a specific therapy (e.g. drug administration versus placebo). Thus, double blinding ensures that the patient or therapy groups are both handled and observed in the same manner. The highest possible degree of blinding should always be selected. The study statistician should also remain blinded until the details of the evaluation have finally been specified.

A well designed clinical study must also include case number planning. This ensures that the assumed therapeutic effect can be recognized as such, with a previously specified statistical probability (statistical power) ( 4 , 6 , 12 ).

It is important for the performance of a clinical trial that it should be carefully planned and that the exact clinical details and methods should be specified in the study protocol ( 13 ). It is, however, also important that the implementation of the study according to the protocol, as well as data collection, must be monitored. For a first class study, data quality must be ensured by double data entry, programming plausibility tests, and evaluation by a biometrician. International recommendations for the reporting of randomized clinical studies can be found in the CONSORT statement (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, www.consort-statement.org ) ( 14 ). Many journals make this an essential condition for publication.

For all the methodological reasons mentioned above and for ethical reasons, the randomized controlled and blinded clinical trial with case number planning is accepted as the gold standard for testing the efficacy and safety of therapies or drugs ( 4 , e1 , 15 ).

In contrast, noninterventional clinical studies (NIS) are patient-related observational studies, in which patients are given an individually specified therapy. The responsible physician specifies the therapy on the basis of the medical diagnosis and the patient’s wishes. NIS include noninterventional therapeutic studies, prognostic studies, observational drug studies, secondary data analyses, case series and single case analyses ( 13 , 16 ). Similarly to clinical studies, noninterventional therapy studies include comparison between therapies; however, the treatment is exclusively according to the physician’s discretion. The evaluation is often retrospective. Prognostic studies examine the influence of prognostic factors (such as tumor stage, functional state, or body mass index) on the further course of a disease. Diagnostic studies are another class of observational studies, in which either the quality of a diagnostic method is compared to an established method (ideally a gold standard), or an investigator is compared with one or several other investigators (inter-rater comparison) or with himself at different time points (intra-rater comparison) ( e1 ). If an event is very rare (such as a rare disease or an individual course of treatment), a single-case study, or a case series, are possibilities. A case series is a study on a larger patient group with a specific disease. For example, after the discovery of the AIDS virus, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the USA collected a case series of 1000 patients, in order to study frequent complications of this infection. The lack of a control group is a disadvantage of case series. For this reason, case series are primarily used for descriptive purposes ( 3 ).

Epidemiological studies

The main point of interest in epidemiological studies is to investigate the distribution and historical changes in the frequency of diseases and the causes for these. Analogously to clinical studies, a distinction is made between experimental and observational epidemiological studies ( 16 , 17 ).

Interventional studies are experimental in character and are further subdivided into field studies (sample from an area, such as a large region or a country) and group studies (sample from a specific group, such as a specific social or ethnic group). One example was the investigation of the iodine supplementation of cooking salt to prevent cretinism in a region with iodine deficiency. On the other hand, many interventions are unsuitable for randomized intervention studies, for ethical, social or political reasons, as the exposure may be harmful to the subjects ( 17 ).

Observational epidemiological studies can be further subdivided into cohort studies (follow-up studies), case control studies, cross-sectional studies (prevalence studies), and ecological studies (correlation studies or studies with aggregated data).

In contrast, studies with only descriptive evaluation are restricted to a simple depiction of the frequency (incidence and prevalence) and distribution of a disease within a population. The objective of the description may also be the regular recording of information (monitoring, surveillance). Registry data are also suited for the description of prevalence and incidence; for example, they are used for national health reports in Germany.

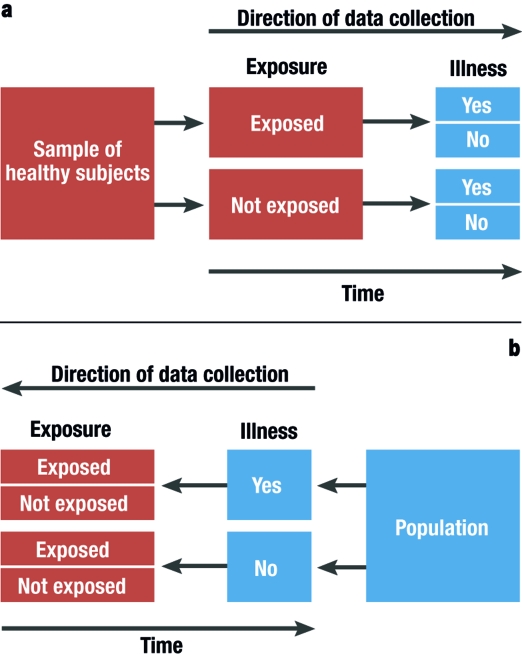

In the simplest case, cohort studies involve the observation of two healthy groups of subjects over time. One group is exposed to a specific substance (for example, workers in a chemical factory) and the other is not exposed. It is recorded prospectively (into the future) how often a specific disease (such as lung cancer) occurs in the two groups ( figure 2a ). The incidence for the occurrence of the disease can be determined for both groups. Moreover, the relative risk (quotient of the incidence rates) is a very important statistical parameter which can be calculated in cohort studies. For rare types of exposure, the general population can be used as controls ( e6 ). All evaluations naturally consider the age and gender distributions in the corresponding cohorts. The objective of cohort studies is to record detailed information on the exposure and on confounding factors, such as the duration of employment, the maximum and the cumulated exposure. One well known cohort study is the British Doctors Study, which prospectively examined the effect of smoking on mortality among British doctors over a period of decades ( e7 ). Cohort studies are well suited for detecting causal connections between exposure and the development of disease. On the other hand, cohort studies often demand a great deal of time, organization, and money. So-called historical cohort studies represent a special case. In this case, all data on exposure and effect (illness) are already available at the start of the study and are analyzed retrospectively. For example, studies of this sort are used to investigate occupational forms of cancer. They are usually cheaper ( 16 ).

Graphical depiction of a prospective cohort study (simplest case [2a]) and a retrospective case control study (2b)

In case control studies, cases are compared with controls. Cases are persons who fall ill from the disease in question. Controls are persons who are not ill, but are otherwise comparable to the cases. A retrospective analysis is performed to establish to what extent persons in the case and control groups were exposed ( figure 2b ). Possible exposure factors include smoking, nutrition and pollutant load. Care should be taken that the intensity and duration of the exposure is analyzed as carefully and in as detailed a manner as possible. If it is observed that ill people are more often exposed than healthy people, it may be concluded that there is a link between the illness and the risk factor. In case control studies, the most important statistical parameter is the odds ratio. Case control studies usually require less time and fewer resources than cohort studies ( 16 ). The disadvantage of case control studies is that the incidence rate (rate of new cases) cannot be calculated. There is also a great risk of bias from the selection of the study population ("selection bias") and from faulty recall ("recall bias") (see too the article "Avoiding Bias in Observational Studies"). Table 1 presents an overview of possible types of epidemiological study ( e8 ). Table 2 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of observational studies ( 16 ).

Table 1. Specially well suited study types for epidemiological investigations (taken from [ e8 ]).

Table 2. advantages and disadvantages of observational studies (taken from [ 16 ])*..

1 = slight; 2 = moderate; 3 = high; N/A, not applicable.

*Individual cases may deviate from this pattern.

Selecting the correct study type is an important aspect of study design (see "Study Design in Medical Research" in volume 11/2009). However, the scientific questions can only be correctly answered if the study is planned and performed at a qualitatively high level ( e9 ). It is very important to consider or even eliminate possible interfering factors (or confounders), as otherwise the result cannot be adequately interpreted. Confounders are characteristics which influence the target parameters. Although this influence is not of primary interest, it can interfere with the connection between the target parameter and the factors that are of interest. The influence of confounders can be minimized or eliminated by standardizing the procedure, stratification ( 18 ), or adjustment ( 19 ).

The decision as to which study type is suitable to answer a specific primary research question must be based not only on scientific considerations, but also on issues related to resources (personnel and finances), hospital capacity, and practicability. Many epidemiological studies can only be implemented if there is access to registry data. The demands for planning, implementation, and statistical evaluation for observational studies should be just as high for observational studies as for experimental studies. There are particularly strict requirements, with legally based regulations (such as the Medicines Act and Good Clinical Practice), for the planning, implementation, and evaluation of clinical studies. A study protocol must be prepared for both interventional and noninterventional studies ( 6 , 13 ). The study protocol must contain information on the conditions, question to be answered (objective), the methods of measurement, the implementation, organization, study population, data management, case number planning, the biometric evaluation, and the clinical relevance of the question to be answered ( 13 ).

Important and justified ethical considerations may restrict studies with optimal scientific and statistical features. A randomized intervention study under strictly controlled conditions of the effect of exposure to harmful factors (such as smoking, radiation, or a fatty diet) is not possible and not permissible for ethical reasons. Observational studies are a possible alternative to interventional studies, even though observational studies are less reliable and less easy to control ( 17 ).

A medical study should always be published in a peer reviewed journal. Depending on the study type, there are recommendations and checklists for presenting the results. For example, these may include a description of the population, the procedure for missing values and confounders, and information on statistical parameters. Recommendations and guidelines are available for clinical studies ( 14 , 20 , e10 , e11 ), for diagnostic studies ( 21 , 22 , e12 ), and for epidemiological studies ( 23 , e13 ). Since 2004, the WHO has demanded that studies should be registered in a public registry, such as www.controlled-trials.com or www.clinicaltrials.gov . This demand is supported by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) ( 24 ), which specifies that the registration of the study before inclusion of the first subject is an essential condition for the publication of the study results ( e14 ).

When specifying the study type and study design for medical studies, it is essential to collaborate with an experienced biometrician. The quality and reliability of the study can be decisively improved if all important details are planned together ( 12 , 25 ).

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Rodney A. Yeates, M.A., Ph.D.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in the sense of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

- 1. Bortz J, Döring N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York; 2002. pp. 39–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Bortz J, Döring N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2002. 37 pp. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. Klinische Epidemiologie. Grundlagen und Anwendung. Bern: Huber; 2007. pp. 1–327. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. 1. Aufl. Boca Raton, London, New York, Washington D.C.: Chapman & Hall; 1991. pp. 1–499. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Schumacher M, Schulgen G. Methodik klinischer Studien. 2. Aufl. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 1–436. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Machin D, Campbell MJ, Fayers PM, Pinol APY. Sample size tables for clinical studies. 2. Aufl. Oxford, London, Berlin: Blackwell Science Ltd.; 1987. pp. 1–303. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Randomization.com: Welcome to randomization.com. http://www.randomization.com/ ; letzte Version: 16. 7. 2008

- 8. Zelen M. The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90015-0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Altman DG. Randomisation: potential for reducing bias. BMJ. 1991;302:1481–1482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1481. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. pp. 120–148. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Types of epidemiologic studies: clinical trials. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: LIPPINCOTT Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 89–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Eng J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology. 2003;227:309–313. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272012051. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Schäfer H, Berger J, Biebler K-E, et al. Empfehlungen für die Erstellung von Studienprotokollen (Studienplänen) für klinische Studien. Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie in Medizin und Biologie. 1999;30:141–154. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:657–662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Machin D, Campbell MJ. Design of studies for medical research. Chichester: Wiley; 2005. pp. 1–286. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Kjellström T. Einführung in die Epidemiologie. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber; 1997. pp. 1–240. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Types of epidemiologic studies. 3rd Edition. Philadelphia: LIPPINCOTT Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 87–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. pp. 149–185. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, Chichester, Brisbane, Toronto, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. pp. 186–219. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. Das CONSORT-Statement: Überarbeitete Empfehlungen zur Qualitätsverbesserung von Reports randomisierter Studien im Parallel-Design. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129:16–20. doi: 10.1007/s00482-004-0380-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1–6. doi: 10.1373/49.1.1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Wald N, Cuckle H. Reporting the assessment of screening and diagnostic tests. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb02411.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. International Committee of Medical Journals (ICMJE) Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. http://www.icmje.org/clin_trial.pdf ; letzte Version: 22.05.2007

- 25. Altman DG, Gore SM, Gardner MJ, Pocock SJ. Statistical guidelines for contributors to medical journals. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:1489–1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6376.1489. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e1. Neugebauer E, Rothmund M, Lorenz W. The concept, structure and practice of prospective clinical studies. Chirurg. 1989;60:203–213. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e2. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH); 2008. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e3. ICH 6: Good Clinical Practice. International Conference on Harmonization; London UK. 1996. adopted by CPMP July 1996 (CPMP/ICH/135/95) [ Google Scholar ]

- e4. ICH 9: Statisticlal Principles for Clinical Trials. International Conference on Harmonization; London UK. 1998. adopted by CPMP July 1998 (CPMP/ICH/363/96) [ Google Scholar ]

- e5. ICH 10: Choice of control group and related issues in clinical trails. International Conference on Harmonization; London UK. 2000. adopted by CPMP July 2000 (CPMP/ICH/363/96) [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e6. Blettner M, Zeeb H, Auvinen A, et al. Mortality from cancer and other causes among male airline cockpit crew in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:946–952. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11328. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e7. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e8. Blettner M, Heuer C, Razum O. Critical reading of epidemiological papers. A guide. Eur J Public Health. 2001;11:97–101. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.1.97. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e9. Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e10. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e11. Novack GD. The CONSORT statement for publication of controlled clinical trials. Ocul Surf. 2004;2:45–46. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70023-x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e12. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Clin Chem. 2003;49:7–18. doi: 10.1373/49.1.7. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e13. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18:805–835. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e14. DeAngelis CD, Razen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. Is this clinical trial fully registered: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. JAMA. 2005;293:2908–2917. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.jed50037. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- e15. Altman DG, Gore SM, Gardner MJ, Pocock SJ. Statistical guidelines for contributors to medical journals. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:1489–1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6376.1489. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (238.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Job Search Advice

- Interviewing

- Login/Register

- Career Profiles and Employment Projections

- Medical Scientists: Jobs, Career, Salary and Education Information

Medical Scientists

Career, salary and education information.

What They Do : Medical scientists conduct research aimed at improving overall human health.

Work Environment : Medical scientists work in offices and laboratories. Most work full time.

How to Become One : Medical scientists typically have a Ph.D., usually in biology or a related life science. Some medical scientists get a medical degree instead of, or in addition to, a Ph.D.

Salary : The median annual wage for medical scientists is $95,310.

Job Outlook : Employment of medical scientists is projected to grow 17 percent over the next ten years, much faster than the average for all occupations.

Related Careers : Compare the job duties, education, job growth, and pay of medical scientists with similar occupations.

Following is everything you need to know about a career as a medical scientist with lots of details. As a first step, take a look at some of the following jobs, which are real jobs with real employers. You will be able to see the very real job career requirements for employers who are actively hiring. The link will open in a new tab so that you can come back to this page to continue reading about the career:

Top 3 Medical Scientist Jobs

Medical Lab Scientist * Discipline: Allied Health Professional * Duration: Ongoing * Shift: 8 hours, flexible * Employment Type: Staff Overview * The Medical Lab Scientist 2 is responsible for ...

Medical Lab Scientist * Discipline: Allied Health Professional * Start Date: 12/02/2024 * Duration: 13 weeks * 40 hours per week * Shift: 8 hours, nights * Employment Type: Travel TRA RN Clinical Lab ...

Medical Lab Scientist * Discipline: Allied Health Professional * Start Date: ASAP * Duration: 13 weeks * 40 hours per week * Shift: 8 hours * Employment Type: Travel Anders Group Job ID #835581. Pay ...

See all Medical Scientist jobs

What Medical Scientists Do [ About this section ] [ To Top ]

Medical scientists conduct research aimed at improving overall human health. They often use clinical trials and other investigative methods to reach their findings.

Duties of Medical Scientists

Medical scientists typically do the following:

- Design and conduct studies that investigate both human diseases and methods to prevent and treat them

- Prepare and analyze medical samples and data to investigate causes and treatment of toxicity, pathogens, or chronic diseases

- Standardize drug potency, doses, and methods to allow for the mass manufacturing and distribution of drugs and medicinal compounds

- Create and test medical devices

- Develop programs that improve health outcomes, in partnership with health departments, industry personnel, and physicians

- Write research grant proposals and apply for funding from government agencies and private funding sources

- Follow procedures to avoid contamination and maintain safety

Many medical scientists form hypotheses and develop experiments, with little supervision. They often lead teams of technicians and, sometimes, students, who perform support tasks. For example, a medical scientist working in a university laboratory may have undergraduate assistants take measurements and make observations for the scientist's research.

Medical scientists study the causes of diseases and other health problems. For example, a medical scientist who does cancer research might put together a combination of drugs that could slow the cancer's progress. A clinical trial may be done to test the drugs. A medical scientist may work with licensed physicians to test the new combination on patients who are willing to participate in the study.

In a clinical trial, patients agree to help determine if a particular drug, a combination of drugs, or some other medical intervention works. Without knowing which group they are in, patients in a drug-related clinical trial receive either the trial drug or a placebo—a pill or injection that looks like the trial drug but does not actually contain the drug.

Medical scientists analyze the data from all of the patients in the clinical trial, to see how the trial drug performed. They compare the results with those obtained from the control group that took the placebo, and they analyze the attributes of the participants. After they complete their analysis, medical scientists may write about and publish their findings.

Medical scientists do research both to develop new treatments and to try to prevent health problems. For example, they may study the link between smoking and lung cancer or between diet and diabetes.

Medical scientists who work in private industry usually have to research the topics that benefit their company the most, rather than investigate their own interests. Although they may not have the pressure of writing grant proposals to get money for their research, they may have to explain their research plans to nonscientist managers or executives.

Medical scientists usually specialize in an area of research within the broad area of understanding and improving human health. Medical scientists may engage in basic and translational research that seeks to improve the understanding of, or strategies for, improving health. They may also choose to engage in clinical research that studies specific experimental treatments.

Work Environment for Medical Scientists [ About this section ] [ To Top ]

Medical scientists hold about 119,200 jobs. The largest employers of medical scientists are as follows:

Medical scientists usually work in offices and laboratories. They spend most of their time studying data and reports. Medical scientists sometimes work with dangerous biological samples and chemicals, but they take precautions that ensure a safe environment.

Medical Scientist Work Schedules

Most medical scientists work full time.

How to Become a Medical Scientist [ About this section ] [ To Top ]

Get the education you need: Find schools for Medical Scientists near you!

Medical scientists typically have a Ph.D., usually in biology or a related life science. Some medical scientists get a medical degree instead of, or in addition to, a Ph.D.

Education for Medical Scientists

Students planning careers as medical scientists generally pursue a bachelor's degree in biology, chemistry, or a related field. Undergraduate students benefit from taking a broad range of classes, including life sciences, physical sciences, and math. Students also typically take courses that develop communication and writing skills, because they must learn to write grants effectively and publish their research findings.

After students have completed their undergraduate studies, they typically enter Ph.D. programs. Dual-degree programs are available that pair a Ph.D. with a range of specialized medical degrees. A few degree programs that are commonly paired with Ph.D. studies are Medical Doctor (M.D.), Doctor of Dental Surgery (D.D.S.), Doctor of Dental Medicine (D.M.D.), Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.), and advanced nursing degrees. Whereas Ph.D. studies focus on research methods, such as project design and data interpretation, students in dual-degree programs learn both the clinical skills needed to be a physician and the research skills needed to be a scientist.

Graduate programs emphasize both laboratory work and original research. These programs offer prospective medical scientists the opportunity to develop their experiments and, sometimes, to supervise undergraduates. Ph.D. programs culminate in a dissertation that the candidate presents before a committee of professors. Students may specialize in a particular field, such as gerontology, neurology, or cancer.

Those who go to medical school spend most of the first 2 years in labs and classrooms, taking courses such as anatomy, biochemistry, physiology, pharmacology, psychology, microbiology, pathology, medical ethics, and medical law. They also learn how to record medical histories, examine patients, and diagnose illnesses. They may be required to participate in residency programs, meeting the same requirements that physicians and surgeons have to fulfill.

Medical scientists often continue their education with postdoctoral work. This provides additional and more independent lab experience, including experience in specific processes and techniques, such as gene splicing. Often, that experience is transferable to other research projects.

Licenses, Certifications, and Registrations for Medical Scientists

Medical scientists primarily conduct research and typically do not need licenses or certifications. However, those who administer drugs or gene therapy or who otherwise practice medicine on patients in clinical trials or a private practice need a license to practice as a physician.

Medical Scientist Training

Medical scientists often begin their careers in temporary postdoctoral research positions or in medical residency. During their postdoctoral appointments, they work with experienced scientists as they continue to learn about their specialties or develop a broader understanding of related areas of research. Graduates of M.D. or D.O. programs may enter a residency program in their specialty of interest. A residency usually takes place in a hospital and varies in duration, generally lasting from 3 to 7 years, depending on the specialty. Some fellowships exist that train medical practitioners in research skills. These may take place before or after residency.

Postdoctoral positions frequently offer the opportunity to publish research findings. A solid record of published research is essential to getting a permanent college or university faculty position.

Work Experience in a Related Occupation for Medical Scientists

Although it is not a requirement for entry, many medical scientists become interested in research after working as a physician or surgeon , or in another medical profession, such as dentist .

Important Qualities for Medical Scientists

Communication skills. Communication is critical, because medical scientists must be able to explain their conclusions. In addition, medical scientists write grant proposals, because grants often are required to fund their research.

Critical-thinking skills. Medical scientists must use their expertise to determine the best method for solving a specific research question.

Data-analysis skills. Medical scientists use statistical techniques, so that they can properly quantify and analyze health research questions.

Decisionmaking skills. Medical scientists must determine what research questions to ask, how best to investigate the questions, and what data will best answer the questions.

Observation skills. Medical scientists conduct experiments that require precise observation of samples and other health-related data. Any mistake could lead to inconclusive or misleading results.

Medical Scientist Salaries [ About this section ] [ More salary/earnings info ] [ To Top ]

The median annual wage for medical scientists is $95,310. The median wage is the wage at which half the workers in an occupation earned more than that amount and half earned less. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $50,100, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $166,980.

The median annual wages for medical scientists in the top industries in which they work are as follows:

Job Outlook for Medical Scientists [ About this section ] [ To Top ]

Employment of medical scientists is projected to grow 17 percent over the next ten years, much faster than the average for all occupations.

About 10,000 openings for medical scientists are projected each year, on average, over the decade. Many of those openings are expected to result from the need to replace workers who transfer to different occupations or exit the labor force, such as to retire.

Employment of Medical Scientists

Demand for medical scientists will stem from greater demand for a variety of healthcare services as the population continues to age and rates of chronic disease continue to increase. These scientists will be needed for research into treating diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and cancer, and problems related to treatment, such as resistance to antibiotics. In addition, medical scientists will continue to be needed for medical research as a growing population travels globally and facilitates the spread of diseases.

The availability of federal funds for medical research grants also may affect opportunities for these scientists.

Careers Related to Medical Scientists [ About this section ] [ To Top ]

Agricultural and food scientists.

Agricultural and food scientists research ways to improve the efficiency and safety of agricultural establishments and products.

Biochemists and Biophysicists

Biochemists and biophysicists study the chemical and physical principles of living things and of biological processes, such as cell development, growth, heredity, and disease.

Epidemiologists

Epidemiologists are public health professionals who investigate patterns and causes of disease and injury in humans. They seek to reduce the risk and occurrence of negative health outcomes through research, community education, and health policy.

Health Educators and Community Health Workers

Health educators teach people about behaviors that promote wellness. They develop and implement strategies to improve the health of individuals and communities. Community health workers collect data and discuss health concerns with members of specific populations or communities.

Medical and Clinical Laboratory Technologists and Technicians

Medical laboratory technologists (commonly known as medical laboratory scientists) and medical laboratory technicians collect samples and perform tests to analyze body fluids, tissue, and other substances.

Microbiologists

Microbiologists study microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, algae, fungi, and some types of parasites. They try to understand how these organisms live, grow, and interact with their environments.

Physicians and Surgeons

Physicians and surgeons diagnose and treat injuries or illnesses. Physicians examine patients; take medical histories; prescribe medications; and order, perform, and interpret diagnostic tests. They counsel patients on diet, hygiene, and preventive healthcare. Surgeons operate on patients to treat injuries, such as broken bones; diseases, such as cancerous tumors; and deformities, such as cleft palates.

Postsecondary Teachers

Postsecondary teachers instruct students in a wide variety of academic and technical subjects beyond the high school level. They may also conduct research and publish scholarly papers and books.

Veterinarians

Veterinarians care for the health of animals and work to improve public health. They diagnose, treat, and research medical conditions and diseases of pets, livestock, and other animals.

More Medical Scientist Information [ About this section ] [ To Top ]

For more information about research specialties and opportunities within specialized fields for medical scientists, visit

American Association for Cancer Research

American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

The American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science

American Society for Clinical Pathology

American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics

The Gerontological Society of America

Infectious Diseases Society of America

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Society for Neuroscience

Society of Toxicology

A portion of the information on this page is used by permission of the U.S. Department of Labor.

Explore more careers: View all Careers or the Top 30 Career Profiles

Search for jobs:.

Research Types Explained: Basic, Clinical, Translational

“Research” is a broad stroke of a word, the verbal equivalent of painting a wall instead of a masterpiece. There are important distinctions among the three principal types of medical research — basic, clinical and translational.

Whereas basic research is looking at questions related to how nature works, translational research aims to take what’s learned in basic research and apply that in the development of solutions to medical problems. Clinical research, then, takes those solutions and studies them in clinical trials. Together, they form a continuous research loop that transforms ideas into action in the form of new treatments and tests, and advances cutting-edge developments from the lab bench to the patient’s bedside and back again.

Basic Research

When it comes to science, the “basic” in basic research describes something that’s an essential starting point. “If you think of it in terms of construction, you can’t put up a beautiful, elegant house without first putting in a foundation,” says David Frank, MD , Associate Professor of Medicine, Medical Oncology, at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “In science, if you don’t first understand the basic research, then you can’t move on to advanced applications.”

Basic medical research is usually conducted by scientists with a PhD in such fields as biology and chemistry, among many others. They study the core building blocks of life — DNA, cells, proteins, molecules, etc. — to answer fundamental questions about their structures and how they work.

For example, oncologists now know that mutations in DNA enable the unchecked growth of cells in cancer. A scientist conducting basic research might ask: How does DNA work in a healthy cell? How do mutations occur? Where along the DNA sequence do mutations happen? And why?

“Basic research is fundamentally curiosity-driven research,” says Milka Kostic, Program Director, Chemical Biology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “Think of that moment when an apple fell on Isaac Newton’s head. He thought to himself, ‘Why did that happen?’ and then went on to try to find the answer. That’s basic research.”

Clinical Research

Clinical research explores whether new treatments, medications and diagnostic techniques are safe and effective in patients. Physicians administer these to patients in rigorously controlled clinical trials, so that they can accurately and precisely monitor patients’ progress and evaluate the treatment’s efficacy, or measurable benefit.

“In clinical research, we’re trying to define the best treatment for a patient with a given condition,” Frank says. “We’re asking such questions as: Will this new treatment extend the life of a patient with a given type of cancer? Could this supportive medication diminish nausea, diarrhea or other side effects? Could this diagnostic test help physicians detect cancer earlier or distinguish between fast- and slow-growing cancers?”

Successful clinical researchers must draw on not only their medical training but also their knowledge of such areas as statistics, controls and regulatory compliance.

Translational Research

It’s neither practical nor safe to transition directly from studying individual cells to testing on patients. Translational research provides that crucial pivot point. It bridges the gap between basic and clinical research by bringing together a number of specialists to refine and advance the application of a discovery. “Biomedical science is so complex, and there’s so much knowledge available.” Frank says. “It’s through collaboration that advances are made.”

For example, let’s say a basic researcher has identified a gene that looks like a promising candidate for targeted therapy. Translational researchers would then evaluate thousands, if not millions, of potential compounds for the ideal combination that could be developed into a medicine to achieve the desired effect. They’d refine and test the compound on intermediate models, in laboratory and animal models. Then they would analyze those test results to determine proper dosage, side effects and other safety considerations before moving to first-in-human clinical trials. It’s the complex interplay of chemistry, biology, oncology, biostatistics, genomics, pharmacology and other specialties that makes such a translational study a success.

Collaboration and technology have been the twin drivers of recent quantum leaps in the quality and quantity of translational research. “Now, using modern molecular techniques,” Frank says, “we can learn so much from a tissue sample from a patient that we couldn’t before.”

Translational research provides a crucial pivot point after clinical trials as well. Investigators explore how the trial’s resulting treatment or guidelines can be implemented by physicians in their practice. And the clinical outcomes might also motivate basic researchers to reevaluate their original assumptions.

“Translational research is a two-way street,” Kostic says. “There is always conversation flowing in both directions. It’s a loop, a continuous cycle, with one research result inspiring another.”

Learn more about research at Dana-Farber .

- Create new account

Medical Scientist

Medical scientists conduct research aimed at improving overall human health. They often use clinical trials and other investigative methods to reach their findings.

Medical scientists typically do the following:

- Design and conduct studies to investigate human diseases and methods to prevent and treat diseases

- Prepare and analyze data from medical samples and investigate causes and treatment of toxicity, pathogens, or chronic diseases

- Standardize drugs' potency, doses, and methods of administering to allow for their mass manufacturing and distribution

- Create and test medical devices

- Follow safety procedures, such as decontaminating workspaces

- Write research grant proposals and apply for funding from government agencies, private funding, and other sources

- Write articles for publication and present research findings

Medical scientists form hypotheses and develop experiments. They study the causes of diseases and other health problems in a variety of ways. For example, they may conduct clinical trials, working with licensed physicians to test treatments on patients who have agreed to participate in the study. They analyze data from the trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment.

Some medical scientists choose to write about and publish their findings in scientific journals after completion of the clinical trial. They also may have to present their findings in ways that nonscientist audiences understand.

Medical scientists often lead teams of technicians or students who perform support tasks. For example, a medical scientist may have assistants take measurements and make observations for the scientist’s research.

Medical scientists usually specialize in an area of research, with the goal of understanding and improving human health outcomes. The following are examples of types of medical scientists:

Clinical pharmacologists research new drug therapies for health problems, such as seizure disorders and Alzheimer’s disease.

Medical pathologists research the human body and tissues, such as how cancer progresses or how certain issues relate to genetics.

Toxicologists study the negative impacts of chemicals and pollutants on human health.

Medical scientists conduct research to better understand disease or to develop breakthroughs in treatment. For information about an occupation that tracks and develops methods to prevent the spread of diseases, see the profile on epidemiologists.

Medical scientists held about 119,200 jobs in 2021. The largest employers of medical scientists were as follows:

Medical scientists typically work in offices and laboratories. In the lab, they sometimes work with dangerous biological samples and chemicals. They must take precautions in the lab to ensure safety, such as by wearing protective gloves, knowing the location of safety equipment, and keeping work areas neat.

Work Schedules

Most medical scientists work full time, and some work more than 40 hours per week.

Medical scientists typically have a Ph.D., usually in biology or a related life science. Some get a medical degree instead of, or in addition to, a Ph.D.

Medical scientists typically need a Ph.D. or medical degree. Candidates sometimes qualify for positions with a master’s degree and experience. Applicants to master’s or doctoral programs typically have a bachelor's degree in biology or a related physical science field, such as chemistry.

Ph.D. programs for medical scientists typically focus on research in a particular field, such as immunology, neurology, or cancer. Through laboratory work, Ph.D. students develop experiments related to their research.

Medical degree programs include Medical Doctor (M.D.), Doctor of Dental Surgery (D.D.S.), Doctor of Dental Medicine (D.M.D.), Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.), Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm.D.), and advanced nursing degrees. In medical school, students usually spend the first phase of their education in labs and classrooms, taking courses such as anatomy, biochemistry, and medical ethics. During their second phase, medical students typically participate in residency programs.

Some medical scientist training programs offer dual degrees that pair a Ph.D. with a medical degree. Students in dual-degree programs learn both the research skills needed to be a scientist and the clinical skills needed to be a healthcare practitioner.

Licenses, Certifications, and Registrations

Medical scientists primarily conduct research and typically do not need licenses or certifications. However, those who practice medicine, such as by treating patients in clinical trials or in private practice, must be licensed as physicians or other healthcare practitioners.

Medical scientists with a Ph.D. may begin their careers in postdoctoral research positions; those with a medical degree often complete a residency. During postdoctoral appointments, Ph.D.s work with experienced scientists to learn more about their specialty area and improve their research skills. Medical school graduates who enter a residency program in their specialty generally spend several years working in a hospital or doctor’s office.

Medical scientists typically have an interest in the Building, Thinking and Creating interest areas, according to the Holland Code framework. The Building interest area indicates a focus on working with tools and machines, and making or fixing practical things. The Thinking interest area indicates a focus on researching, investigating, and increasing the understanding of natural laws. The Creating interest area indicates a focus on being original and imaginative, and working with artistic media.

If you are not sure whether you have a Building or Thinking or Creating interest which might fit with a career as a medical scientist, you can take a career test to measure your interests.

Medical scientists should also possess the following specific qualities:

Communication skills. Communication is critical, because medical scientists must be able to explain their conclusions. In addition, medical scientists write grant proposals, which are often required to continue their research.

Critical-thinking skills. Medical scientists must use their expertise to determine the best method for solving a specific research question.

Data-analysis skills. Medical scientists use statistical techniques, so that they can properly quantify and analyze health research questions.

Decision-making skills. Medical scientists must use their expertise and experience to determine what research questions to ask, how best to investigate the questions, and what data will best answer the questions.

Observation skills. Medical scientists conduct experiments that require precise observation of samples and other health data. Any mistake could lead to inconclusive or misleading results.

The median annual wage for medical scientists was $95,310 in May 2021. The median wage is the wage at which half the workers in an occupation earned more than that amount and half earned less. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $50,100, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $166,980.

In May 2021, the median annual wages for medical scientists in the top industries in which they worked were as follows:

Employment of medical scientists is projected to grow 17 percent from 2021 to 2031, much faster than the average for all occupations.

About 10,000 openings for medical scientists are projected each year, on average, over the decade. Many of those openings are expected to result from the need to replace workers who transfer to different occupations or exit the labor force, such as to retire.

Demand for medical scientists will stem from greater demand for a variety of healthcare services as the population continues to age and rates of chronic disease continue to increase. These scientists will be needed for research into treating diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and cancer, and problems related to treatment, such as resistance to antibiotics. In addition, medical scientists will continue to be needed for medical research as a growing population travels globally and facilitates the spread of diseases.

The availability of federal funds for medical research grants also may affect opportunities for these scientists.

For more information about research specialties and opportunities within specialized fields for medical scientists, visit

American Association for Cancer Research

American Physician Scientists Association

American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

The American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science

American Society for Clinical Pathology

American Society for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics

The Gerontological Society of America

Infectious Diseases Society of America

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Society for Neuroscience

Society of Toxicology

Where does this information come from?

The career information above is taken from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Outlook Handbook . This excellent resource for occupational data is published by the U.S. Department of Labor every two years. Truity periodically updates our site with information from the BLS database.

I would like to cite this page for a report. Who is the author?

There is no published author for this page. Please use citation guidelines for webpages without an author available.

I think I have found an error or inaccurate information on this page. Who should I contact?

This information is taken directly from the Occupational Outlook Handbook published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Truity does not editorialize the information, including changing information that our readers believe is inaccurate, because we consider the BLS to be the authority on occupational information. However, if you would like to correct a typo or other technical error, you can reach us at [email protected] .

I am not sure if this career is right for me. How can I decide?

There are many excellent tools available that will allow you to measure your interests, profile your personality, and match these traits with appropriate careers. On this site, you can take the Career Personality Profiler assessment, the Holland Code assessment, or the Photo Career Quiz .

Get Our Newsletter

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-.

InformedHealth.org [Internet].

In brief: what types of studies are there.

Last Update: March 25, 2020 ; Next update: 2024.

There are various types of scientific studies such as experiments and comparative analyses, observational studies, surveys, or interviews. The choice of study type will mainly depend on the research question being asked.

When making decisions, patients and doctors need reliable answers to a number of questions. Depending on the medical condition and patient's personal situation, the following questions may be asked:

- What is the cause of the condition?

- What is the natural course of the disease if left untreated?

- What will change because of the treatment?

- How many other people have the same condition?

- How do other people cope with it?

Each of these questions can best be answered by a different type of study.

In order to get reliable results, a study has to be carefully planned right from the start. One thing that is especially important to consider is which type of study is best suited to the research question. A study protocol should be written and complete documentation of the study's process should also be done. This is vital in order for other scientists to be able to reproduce and check the results afterwards.

The main types of studies are randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies and qualitative studies.

- Randomized controlled trials

If you want to know how effective a treatment or diagnostic test is, randomized trials provide the most reliable answers. Because the effect of the treatment is often compared with "no treatment" (or a different treatment), they can also show what happens if you opt to not have the treatment or diagnostic test.

When planning this type of study, a research question is stipulated first. This involves deciding what exactly should be tested and in what group of people. In order to be able to reliably assess how effective the treatment is, the following things also need to be determined before the study is started:

- How long the study should last

- How many participants are needed

- How the effect of the treatment should be measured

For instance, a medication used to treat menopause symptoms needs to be tested on a different group of people than a flu medicine. And a study on treatment for a stuffy nose may be much shorter than a study on a drug taken to prevent strokes .

“Randomized” means divided into groups by chance. In RCTs participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more groups. Then one group receives the new drug A, for example, while the other group receives the conventional drug B or a placebo (dummy drug). Things like the appearance and taste of the drug and the placebo should be as similar as possible. Ideally, the assignment to the various groups is done "double blinded," meaning that neither the participants nor their doctors know who is in which group.

The assignment to groups has to be random in order to make sure that only the effects of the medications are compared, and no other factors influence the results. If doctors decided themselves which patients should receive which treatment, they might – for instance – give the more promising drug to patients who have better chances of recovery. This would distort the results. Random allocation ensures that differences between the results of the two groups at the end of the study are actually due to the treatment and not something else.

Randomized controlled trials provide the best results when trying to find out if there is a causal relationship. That means finding out whether a certain effect is actually due to the medication being tested. RCTs can answer questions such as these:

- Is the new drug A better than the standard treatment for medical condition X?

- Does regular physical activity speed up recovery after a slipped disc when compared to passive waiting?

- Cohort studies

A cohort is a group of people who are observed frequently over a period of many years – for instance, to determine how often a certain disease occurs. In a cohort study, two (or more) groups that are exposed to different things are compared with each other: For example, one group might smoke while the other doesn't. Or one group may be exposed to a hazardous substance at work, while the comparison group isn't. The researchers then observe how the health of the people in both groups develops over the course of several years, whether they become ill, and how many of them pass away. Cohort studies often include people who are healthy at the start of the study. Cohort studies can have a prospective (forward-looking) design or a retrospective (backward-looking) design. In a prospective study, the result that the researchers are interested in (such as a specific illness) has not yet occurred by the time the study starts. But the outcomes that they want to measure and other possible influential factors can be precisely defined beforehand. In a retrospective study, the result (the illness) has already occurred before the study starts, and the researchers look at the patient's history to find risk factors.

Cohort studies are especially useful if you want to find out how common a medical condition is and which factors increase the risk of developing it. They can answer questions such as:

- How does high blood pressure affect heart health?

- Does smoking increase your risk of lung cancer?

For example, one famous long-term cohort study observed a group of 40,000 British doctors, many of whom smoked. It tracked how many doctors died over the years, and what they died of. The study showed that smoking caused a lot of deaths, and that people who smoked more were more likely to get ill and die.

- Case-control studies

Case-control studies compare people who have a certain medical condition with people who do not have the medical condition, but who are otherwise as similar as possible, for example in terms of their sex and age. Then the two groups are interviewed, or their medical files are analyzed, to find anything that might be risk factors for the disease. So case-control studies are generally retrospective.

Case-control studies are one way to gain knowledge about rare diseases. They are also not as expensive or time-consuming as RCTs or cohort studies. But it is often difficult to tell which people are the most similar to each other and should therefore be compared with each other. Because the researchers usually ask about past events, they are dependent on the participants’ memories. But the people they interview might no longer remember whether they were, for instance, exposed to certain risk factors in the past.

Still, case-control studies can help to investigate the causes of a specific disease, and answer questions like these:

- Do HPV infections increase the risk of cervical cancer ?

- Is the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (“cot death”) increased by parents smoking at home?

Cohort studies and case-control studies are types of "observational studies."

- Cross-sectional studies

Many people will be familiar with this kind of study. The classic type of cross-sectional study is the survey: A representative group of people – usually a random sample – are interviewed or examined in order to find out their opinions or facts. Because this data is collected only once, cross-sectional studies are relatively quick and inexpensive. They can provide information on things like the prevalence of a particular disease (how common it is). But they can't tell us anything about the cause of a disease or what the best treatment might be.

Cross-sectional studies can answer questions such as these:

- How tall are German men and women at age 20?

- How many people have cancer screening?

- Qualitative studies

This type of study helps us understand, for instance, what it is like for people to live with a certain disease. Unlike other kinds of research, qualitative research does not rely on numbers and data. Instead, it is based on information collected by talking to people who have a particular medical condition and people close to them. Written documents and observations are used too. The information that is obtained is then analyzed and interpreted using a number of methods.

Qualitative studies can answer questions such as these:

- How do women experience a Cesarean section?

- What aspects of treatment are especially important to men who have prostate cancer ?

- How reliable are the different types of studies?

Each type of study has its advantages and disadvantages. It is always important to find out the following: Did the researchers select a study type that will actually allow them to find the answers they are looking for? You can’t use a survey to find out what is causing a particular disease, for instance.

It is really only possible to draw reliable conclusions about cause and effect by using randomized controlled trials. Other types of studies usually only allow us to establish correlations (relationships where it isn’t clear whether one thing is causing the other). For instance, data from a cohort study may show that people who eat more red meat develop bowel cancer more often than people who don't. This might suggest that eating red meat can increase your risk of getting bowel cancer. But people who eat a lot of red meat might also smoke more, drink more alcohol , or tend to be overweight . The influence of these and other possible risk factors can only be determined by comparing two equal-sized groups made up of randomly assigned participants.

That is why randomized controlled trials are usually the only suitable way to find out how effective a treatment is. Systematic reviews, which summarize multiple RCTs , are even better. In order to be good-quality, though, all studies and systematic reviews need to be designed properly and eliminate as many potential sources of error as possible.

- Greenhalgh T. Einführung in die Evidence-based Medicine: kritische Beurteilung klinischer Studien als Basis einer rationalen Medizin. Bern: Huber; 2003.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG, Germany). General methods . Version 5.0. Cologne: IQWiG; 2017.

- Klug SJ, Bender R, Blettner M, Lange S. Wichtige epidemiologische Studientypen . Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2004; 129: T7-T10. [ PubMed : 17530597 ]

- Schäfer T. Kritische Bewertung von Studien zur Ätiologie. In: Kunz R, Ollenschläger G, Raspe H, Jonitz G, Donner-Banzhoff N (Ed). Lehrbuch evidenzbasierte Medizin in Klinik und Praxis. Cologne: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; 2007.

IQWiG health information is written with the aim of helping people understand the advantages and disadvantages of the main treatment options and health care services.

Because IQWiG is a German institute, some of the information provided here is specific to the German health care system. The suitability of any of the described options in an individual case can be determined by talking to a doctor. informedhealth.org can provide support for talks with doctors and other medical professionals, but cannot replace them. We do not offer individual consultations.

Our information is based on the results of good-quality studies. It is written by a team of health care professionals, scientists and editors, and reviewed by external experts. You can find a detailed description of how our health information is produced and updated in our methods.

- Cite this Page InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. In brief: What types of studies are there? [Updated 2020 Mar 25].

In this Page

Informed health links, related information.

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- In brief: What types of studies are there? - InformedHealth.org In brief: What types of studies are there? - InformedHealth.org

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

On Oct. 1, 2024, the FDA began implementing a reorganization impacting many parts of the agency. We are in the process of updating FDA.gov content to reflect these changes.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- For Patients

- Clinical Trials: What Patients Need to Know

What Are the Different Types of Clinical Research?

Different types of clinical research are used depending on what the researchers are studying. Below are descriptions of some different kinds of clinical research.

Treatment Research generally involves an intervention such as medication, psychotherapy, new devices, or new approaches to surgery or radiation therapy.

Prevention Research looks for better ways to prevent disorders from developing or returning. Different kinds of prevention research may study medicines, vitamins, vaccines, minerals, or lifestyle changes.

Diagnostic Research refers to the practice of looking for better ways to identify a particular disorder or condition.

Screening Research aims to find the best ways to detect certain disorders or health conditions.

Quality of Life Research explores ways to improve comfort and the quality of life for individuals with a chronic illness.

Genetic studies aim to improve the prediction of disorders by identifying and understanding how genes and illnesses may be related. Research in this area may explore ways in which a person’s genes make him or her more or less likely to develop a disorder. This may lead to development of tailor-made treatments based on a patient’s genetic make-up.

Epidemiological studies seek to identify the patterns, causes, and control of disorders in groups of people.

An important note: some clinical research is “outpatient,” meaning that participants do not stay overnight at the hospital. Some is “inpatient,” meaning that participants will need to stay for at least one night in the hospital or research center. Be sure to ask the researchers what their study requires.

Phases of clinical trials: when clinical research is used to evaluate medications and devices Clinical trials are a kind of clinical research designed to evaluate and test new interventions such as psychotherapy or medications. Clinical trials are often conducted in four phases. The trials at each phase have a different purpose and help scientists answer different questions.

Phase I trials Researchers test an experimental drug or treatment in a small group of people for the first time. The researchers evaluate the treatment’s safety, determine a safe dosage range, and identify side effects.