Ten types of PhD supervisor relationships – which is yours?

Lecturer, Griffith University

Disclosure statement

Susanna Chamberlain does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Griffith University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

It’s no secret that getting a PhD is a stressful process .

One of the factors that can help or hinder this period of study is the relationship between supervisor and student. Research shows that effective supervision can significantly influence the quality of the PhD and its success or failure.

PhD supervisors tend to fulfil several functions: the teacher; the mentor who can support and facilitate the emotional processes; and the patron who manages the springboard from which the student can leap into a career.

There are many styles of supervision that are adopted – and these can vary depending on the type of research being conducted and subject area.

Although research suggests that providing extra mentoring support and striking the right balance between affiliation and control can help improve PhD success and supervisor relationships, there is little research on the types of PhD-supervisor relationships that occur.

From decades of experience of conducting and observing PhD supervision, I’ve noticed ten types of common supervisor relationships that occur. These include:

The candidate is expected to replicate the field, approach and worldview of the supervisor, producing a sliver of research that supports the supervisor’s repute and prestige. Often this is accompanied by strictures about not attempting to be too “creative”.

Cheap labour

The student becomes research assistant to the supervisor’s projects and becomes caught forever in that power imbalance. The patron-client roles often continue long after graduation, with the student forever cast in the secondary role. Their own work is often disregarded as being unimportant.

The “ghost supervisor”

The supervisor is seen rarely, responds to emails only occasionally and has rarely any understanding of either the needs of the student or of their project. For determined students, who will work autonomously, the ghost supervisor is often acceptable until the crunch comes - usually towards the end of the writing process. For those who need some support and engagement, this is a nightmare.

The relationship is overly familiar, with the assurance that we are all good friends, and the student is drawn into family and friendship networks. Situations occur where the PhD students are engaged as babysitters or in other domestic roles (usually unpaid because they don’t want to upset the supervisor by asking for money). The chum, however, often does not support the student in professional networks.

Collateral damage

When the supervisor is a high-powered researcher, the relationship can be based on minimal contact, because of frequent significant appearances around the world. The student may find themselves taking on teaching, marking and administrative functions for the supervisor at the cost of their own learning and research.

The practice of supervision becomes a method of intellectual torment, denigrating everything presented by the student. Each piece of research is interrogated rigorously, every meeting is an inquisition and every piece of writing is edited into oblivion. The student is given to believe that they are worthless and stupid.

Creepy crawlers

Some supervisors prefer to stalk their students, sometimes students stalk their supervisors, each with an unhealthy and unrequited sexual obsession with the other. Most Australian universities have moved actively to address this relationship, making it less common than in previous decades.

Captivate and con

Occasionally, supervisor and student enter into a sexual relationship. This can be for a number of reasons, ranging from a desire to please to a need for power over youth. These affairs can sometimes lead to permanent relationships. However, what remains from the supervisor-student relationship is the asymmetric set of power balances.

Almost all supervision relationships contain some aspect of the counsellor or mentor, but there is often little training or desire to develop the role and it is often dismissed as pastoral care. Although the life experiences of students become obvious, few supervisors are skilled in dealing with the emotional or affective issues.

Colleague in training

When a PhD candidate is treated as a colleague in training, the relationship is always on a professional basis, where the individual and their work is held in respect. The supervisor recognises that their role is to guide through the morass of regulation and requirements, offer suggestions and do some teaching around issues such as methodology, research practice and process, and be sensitive to the life-cycle of the PhD process. The experience for both the supervisor and student should be one of acknowledgement of each other, recognising the power differential but emphasising the support at this time. This is the best of supervision.

There are many university policies that move to address a lot of the issues in supervisor relationships , such as supervisor panels, and dedicated training in supervising and mentoring practices. However, these policies need to be accommodated into already overloaded workloads and should include regular review of supervisors.

- professional mentoring

- PhD supervisors

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges

Case Management Lead (Employment Compliance)

Commissioning Editor Nigeria

Professor in Physiotherapy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Supervisor-PhD Student Relationship: A recipe for success

by Glenn Stevens

Embarking on a doctoral journey is a significant and challenging undertaking. The success of this academic pursuit is not solely determined by individual effort but is often intricately tied to the quality of the relationship between a PhD student and their supervisor. A successful supervisor-student relationship is crucial for navigating the complex terrain of research, overcoming obstacles, and ultimately achieving academic success. In this post, we consider the main features that contribute to a thriving and productive collaboration between supervisors and their PhD students.

Clear Communication:

Effective communication is the cornerstone of any successful relationship, and the supervisor-PhD student dynamic is no exception. Open and transparent communication ensures that expectations, goals, and timelines are clearly understood by both parties. Regular meetings, email correspondence, and constructive feedback are essential components of fostering a communicative and supportive environment.

Mutual Respect and Trust:

A successful relationship is built on mutual respect and trust. PhD students should feel valued for their ideas and contributions, while supervisors should trust in the student’s abilities and dedication. This foundation of respect and trust creates an environment where both parties feel comfortable sharing thoughts, concerns, and uncertainties without fear of judgment.

Guidance and Mentorship:

A supervisor is not just an overseer but a mentor who guides and supports the student throughout their academic journey. This involves providing constructive feedback, offering valuable insights, and helping the student navigate the complexities of their research. A good supervisor is invested in the intellectual and personal development of their students, helping them grow into independent researchers.

Setting Realistic Expectations:

Clarity in setting realistic expectations is crucial. Both parties should have a clear understanding of the project’s scope, milestones, and timelines. Setting achievable goals ensures that the student feels a sense of accomplishment and progress, while the supervisor can gauge the project’s trajectory and offer timely assistance if needed.

Flexibility and Adaptability:

Research is often an unpredictable journey with unexpected challenges. A successful supervisor understands the need for flexibility and adapts to evolving circumstances. Likewise, PhD students should be open to adjusting their research plans as new insights emerge. A dynamic and adaptable approach fosters resilience and creative problem-solving.

Encouraging Independence:

While guidance is essential, a successful supervisor-PhD student relationship encourages the development of the student’s independence. Empowering the student to make decisions, solve problems, and take ownership of their research enhances their academic autonomy and prepares them for a successful career beyond the doctoral program.

Constructive Feedback:

Constructive criticism is a crucial aspect of academic growth. A successful supervisor provides feedback that is specific, actionable, and aimed at improvement. PhD students, in turn, should be receptive to feedback, using it as a tool for refinement and advancement.

Key takeaway

In the world of academia, the journey from a novice researcher to a seasoned scholar is often challenging but immensely rewarding. The success of this journey is greatly influenced by the strength of the supervisor-PhD student relationship. By fostering clear communication, mutual respect, effective mentorship, and a collaborative spirit, both parties contribute to an environment where intellectual growth and academic achievement thrive. Ultimately, a successful supervisor-PhD student relationship is a partnership built on trust, guidance, and a shared commitment to the pursuit of knowledge. In the unlikely event you feel you want to change your supervisor remember you will need to find someone with a vacant spot and with knowledge of your specialty which would be difficult to find.

Recommended reading

Phillips, E., & Johnson, C. (2022). How to Get a PhD: A handbook for students and their supervisors 7e . McGraw-Hill Education (UK). (Click to view on Amazon #Ad)

How to Get a PhD 7e provides a practical and realistic approach for all students who are embarking on a PhD. In addition, supervisors will find invaluable tips on their role in the process, good supervisory practices and how to support students to work effectively.

Glenn Stevens

Glenn is an academic writing and research specialist with 15 years experience as a writing coach and PhD supervisor. Also a qualified English teacher, he previously had an extensive career in publishing. He is currently the editor of this website. Glenn lives in the UK. Contact Glenn Useful article? Why not buy Glenn a Coffee!

Share this:

Tags: phd supervisor

You may also like...

PhD Thesis vs. Masters Dissertation: Making the Transition

by Glenn Stevens · Published

Implications and Recommendations in Research

PhD Viva Preparation: Importance of Remembering Key Facts

- Next story Cost of proofreading: How much to proofread my academic writing?

- Previous story Purposive Sampling in Research

- Academic Writing Service

- Privacy Policy

Useful articles? Why not buy the author a coffee using the link below.

academic research academic writing AI Artificial intelligence case study ChatGPT data dissertation doctorate Editing ethics focus groups generalizability interviews Introduction leadership Literature review management masters methodology methods mixed methods Paraphrasing phd plagiarism proofreading proof reading psychology qualitative qualitative research quantitative quantitative research research research design researcher sampling student students supervisor survey technology theory undergraduate university Writing

A model for the supervisor–doctoral student relationship

- Open access

- Published: 05 February 2009

- Volume 58 , pages 359–373, ( 2009 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Tim Mainhard 1 ,

- Roeland van der Rijst 1 ,

- Jan van Tartwijk 1 &

- Theo Wubbels 1

30k Accesses

134 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The supervisor–doctoral student interpersonal relationship is important for the success of a PhD-project. Therefore, information about doctoral students’ perceptions of their relationship with their supervisor can be useful for providing detailed feedback to supervisors aiming at improving the quality of their supervision. This paper describes the development of the questionnaire on supervisor–doctoral student interaction (QSDI). This questionnaire aims at gathering information about doctoral students’ perceptions of the interpersonal style of their supervisor. The QSDI appeared to be a reliable and valid instrument. It can be used in research on the relationship between supervisor and doctoral student and can provide supervisors with feedback on their interpersonal style towards a particular student.

Similar content being viewed by others

Latent profile of master-student communication and impact on supervisor-postgraduate relationship

Exploring and understanding perceived relationships between doctoral students and their supervisors in China

Assessment of psychometric properties of the questionnaire on supervisor-doctoral student interaction (QSDI) in Iran

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper describes the development and quality of the questionnaire on supervisor–doctoral student interaction (QSDI). The QSDI is aimed at gathering information about doctoral students’ perceptions of the interpersonal style of their supervisor. The results of this questionnaire can be useful for giving detailed feedback to doctoral student supervisors on their interpersonal style towards a particular student and for research on this relationship.

In most research universities in the Anglo-Saxon countries and counties like the Netherlands, PhD candidates do a research study under the supervision of one or two faculty members. These faculty members not only guide and support the PhD candidate, but also play an important role in the assessment of the quality of the final manuscript submitted. Heath ( 2002 ) argues that the success of the PhD system heavily depends on the supervisors, who must provide the time, expertise and support to foster the candidate’s research skills and attitudes, and to ensure the production of a thesis of acceptable standard. Importantly he concludes from analyses of PhD students’ views on supervision that, although the frequency of meetings between supervisor and candidate is essential, the quality of these meetings is even more (cf. Li and Seale 2007 ). Unfortunately, however, there seems to be more research on the frequency of contact than on its quality (e.g., Pearson 1996 ).

Research indicates that the supervisor–doctoral student interpersonal relationship is important for the success of a PhD-project (Golde 2000 ; Kam 1997 ; Marsh et al. 2002 ; McAlpine and Norton 2006 ). Ives and Rowley ( 2005 ) for example reported that good interpersonal working relationships between supervisors and their PhD students were associated with good progress and student satisfaction. Studies of mentoring showed that in particular the psychosocial aspect of mentoring was connected to the protégé’s sense of competence, confidence and role effectiveness (Luna and Cullen 1998 ; Paglis et al. 2006 ). Denicolo ( 2004 ) reports that in the eyes of PhD students positive attributes of supervisors are amongst others reliable, confidence in the student, encouraging, knowledgeable, informative, and sharing. Supervisors should have listening skills, encourage argument and debate, provide continuous feedback and support, be enthusiastic, and show warmth and understanding. Seagram et al. ( 1998 ) showed that important positive characteristics of supervisors according to their doctoral students were professional, pleasant, and supportive behavior.

Problems in the supervisory relationship

Several problems in the supervisor–doctoral candidate relationship may emerge; here we list a few.

First, a certain tension might exist between the supportive helping role of the supervisor and the requirements of the role to warrant dissertation quality. Murphy et al. ( 2007 ) refer to this double role of assessor and guide. Hockey ( 1996 , p. 363) cites Rapoport (1989): “… the significance of the relationship stems from its duality; the co-existence of intimacy, care and personal commitment on the one hand, and commitment to specific academic goals on the other”. Holligan ( 2005 ) analyses this tension in a case study on the conflicting demands put on the supervisor by the research production requirements of an institution versus the support of the PhD student’s autonomy and independence.

Second, a supervisory style that is apt for a particular student could be at odds with the preferred style of the supervisor, or the style he or she is competent to provide. An example of a broadly found distinction in style is what Sinclair ( 2004 ) calls a “hands on” approach that is relatively interventionist and a “hands off” approach that leaves candidates to their own devices. The candidates’ needs for one of these approaches may depend on the phase of their project. The ideal mentor scale of Rose ( 2003 ) has among others been developed to help resolve this problem. The problem of misalignment of supervisor’s and candidate’s style could also be found in the orientation towards supervision, for example in the field of task or person orientation such as distinguished by Murphy et al. ( 2007 ).

Finally, in many institutions it is not common to evaluate supervisory experience or discuss among staff how supervision is (or should be) provided. Nonetheless, such discussions might be profitable for the quality of the PhD students’ work. Leonard et al. ( 2006 ) conclude in a review of the literature on the impact of the working context and support of postgraduate research students that several studies show a need for supervisors to be more aware of the way in which their relationship with a student is developing. Being unaware of the development of the supervisory relationship, both at the part of the supervisor and the candidate, may be a major threat for the development of supervisory trajectories into a productive direction.

Perceptions and evaluations

With the QSDI one can collect data on doctoral candidates’ perceptions of the relationship with their supervisor. Although instruments to collect such data do not exist, data on students’ perceptions of learning environments have been used extensively in educational research and in professional development activities both in secondary and tertiary education. Several reviews of the validity of students’ evaluation of the effectiveness of instruction in universities have been carried out. Composite judgements of students display high validity and reliability (d’Appolonia and Abrami 1997 ; Braskamp and Ory 1994 ; Cashin and Downey 1992 ; Marsh and Roche 1997 ). Marsh et al. ( 2002 ) conclude that, with careful attention to measurement and theoretical issues, students’ evaluations of teaching are reliable and stable. Another reason to investigate students’ perceptions of supervisors’ behaviors is the use as a feedback instrument: student perceptions mediate between the supervisor behaviour and effects on the students (Shuell 1996 ).

Marsh et al. ( 2002 ) indicate that, although there is a vast body of research on undergraduate students’ evaluations of teacher classroom effectiveness, only few studies on the supervision of research and PhD students have been carried out. Not only little research systematically employed student questionnaires to evaluate the quality of the PhD research supervision, but even an instrument is missing that is specific for the doctoral student experience of the relationship with their supervisor. Several more general supervisory instruments have been used such as the supervisory style inventory (Nelson and Friedlander 2001 ) but this questionnaire is not thoroughly adjusted for the situation of PhD candidates. The ideal mentor scale (Rose 2003 , 2005 ) clearly has relevance for the supervisor PhD candidate relationship. By aiming at the assessment of the communication it wants to improve satisfaction with doctoral education by giving a means to align mentor’s and candidate’s profiles. It includes three subscales: integrity, guidance, and relationship that, however, in a study by Bell-Ellison and Dedrick ( 2008 ) were not consistently replicated. This questionnaire is grounded in the literature on mentor’s roles in life time development and therefore emphasizes features slightly different from characteristics of the PhD supervisory relationship.

On the other hand, more specific instruments have been used for the PhD situation. These usually include many different aspects of this situation (e.g., Anderson and Seashore-Louis 1994 ; Marsh et al. 2002 ) and thus do not give detailed information on the interpersonal relationships.

Theoretical framework

The research presented in this paper studies supervision of doctoral students from an interpersonal perspective. The interpersonal perspective describes and analyzes supervision in terms of the relationship between the supervisor and the doctoral student. Two elements are central to this perspective: the communicative systems approach and a model to describe the relationship aspect of supervisor behavior.

A major axiom of the systems approach to communication (Watzlawick et al. 1967 ) is that all behavior has a content and relationship aspect. This implies that supervisor behavior not only carries the content of the words being used, but also has an underlying relationship message. Interaction can be regarded as the exchange of content and relationship messages. When people interact for a longer period of time, mutual expectations will develop and, based on these expectations, patterns can be identified in the exchange of relationship messages. The patterns in the relationship messages that are communicated by the behavior of the people involved in a social system can be regarded as their interpersonal style in a relationship. What the style of a person in a relationship looks like is dependent on both parties in the communication. That means that how a relationship develops into a pattern depends on the behaviors of both parties. Therefore someone’s style depends also on the other in the communication and the style that someone displays may vary over different relationships of a person.

To describe this relationship-aspect of the supervisor behavior, we use a model developed by Wubbels et al. ( 2006 ) to analyze teacher behavior: the model of interpersonal teacher behavior. This model is based on Leary’s interpersonal circle (Leary 1957 ) in which the relationship aspect of behavior is described using an Influence and a Proximity dimension.

Although these two dimensions have occasionally been given other names, they have generally been accepted as universal descriptors of human interaction (e.g., Fiske et al. 2007 ; Judd et al. 2005 ). For the PhD supervisor–student relationship Gatfield ( 2005 ) in his model describes management styles with the help of two similar dimensions: structure and support. Lindén ( 1999 ) in a narrative study mentions two aspects of relationships: freedom and control, which seems to cover a smaller part of the relationship than the model by Wubbels et al. ( 2006 ). Murphy et al. ( 2007 ) studied supervisors’ and PhD candidates’ beliefs about higher degree supervision and reported controlling and guiding beliefs. These aspects clearly are present in the model used in our study.

The two dimensions of the model for interpersonal supervisor behavior, represented as two axes, underlie eight types of behavior: leadership, helpful/friendly, understanding, giving students freedom and responsibility, uncertain, dissatisfied, admonishing and strict (see Fig. 1 ).

The model for interpersonal supervisor behavior

An important aspect of our model is that the dimensions map a degree of behavior. A behavior that a supervisor displays has a degree of Influence and Proximity. The higher the degree of Influence the higher the behavior is displayed on the vertical axis and similarly for the degree of Proximity on the horizontal axis. For the eight sectors this means that the closer a behavior is to the center of the model the lower the intensity of the behavior is.

Another characteristic of our model is that the dimensions are independent. One might feel that showing behavior with a high degree of Influence needs to imply to be close to the other person, or the other way around that Influence always implies to be also a bit to the left on the Proximity dimension, showing oppositional behavior. However, such associations are not necessarily: high Influence behaviors as well as low Influence behaviors can go together with high or low Proximity behaviors. For example, a supervisor may provide guidance either by setting strict rules solely based on his/her own experience (high Influence, somewhat opposition) or by anticipating on or adapting to the student’s wishes (high Influence, somewhat cooperation). In this sense our model provides a richer description of the relationships than is provided by Gatfield ( 2005 ) who refers to poles instead of degrees of intensity of behavior.

Gatfield ( 2005 ) identified four supervisory styles by combining the two poles of the dimensions structure and support. The laissez faire type (low structure and low support) in terms of the sectors of our model for interpersonal teacher behavior primarily offers students responsibility and freedom. The pastoral type (high on support and low on structure) combines understanding and helpful and friendly behavior, whereas for the contractual style (high on support and high on structure) the emphasis is on leadership and helpful friendly behavioral aspects. Finally, Gatfield’s directorial type (high structure, low support) is employing a lot of strict and leadership behavior.

Based on the model of interpersonal teacher behavior, Wubbels et al. ( 2006 ) have developed the questionnaire on teacher interaction (QTI). This instrument can be used to gather information about teachers’ interpersonal styles in teacher–students communication in secondary classrooms (for an overview of the development of this questionnaire and research findings based on data gathered with this instrument, see Wubbels et al. 2006 ). The original Dutch version consists of 77 items that are answered on a five-point Likert scale. Several studies have been conducted on the reliability and validity of the QTI. In all these studies both reliability and validity were satisfying (Wubbels et al. 2006 ). The instrument exists in several languages, amongst others Dutch, English, French, Hebrew, Slovenian, and Turkish.

Later, the QTI was adapted to other educational settings, such as the interaction between student teacher and supervising teacher in teacher education (QSI; Kremer-Hayon and Wubbels 1993a ), and the interaction between school principals and their teachers in primary and secondary education (Kremer-Hayon and Wubbels 1993b ). The student teacher-supervising teacher situation resembles the PhD student supervisor situation. Similar to the interaction between student teacher and supervising teacher, the interaction between PhD student and supervisor is a one-to-one interaction, rather than a one-to-many interaction.

The present paper describes the development of the questionnaire on supervisor–doctoral student interaction (QSDI) as an adaptation of the QTI and the QSI by Kremer-Hayon and Wubbels ( 1993a ). The doctoral student supervisor interaction is a bi-directional relationship with both parties influencing the developing communication pattern. Because we want to use the QSDI for feedback purposes toward the supervisor we focus on measuring the style of the supervisor from the perspective of the doctoral student. Note that although we write about the interpersonal style of the supervisor, we always mean the style in relation to a particular student. What this style looks like depends on the behavior of the doctoral student as well.

Procedure and instruments

In order to represent the model for supervisor behavior (Fig. 1 ), the QSDI has to have eight scales corresponding to the eight sectors of the model. To represent the theoretical model the scales have to be ordered in a circumplex structure; this implies that two independent factors should underlie the eight scales. Every scale therefore should correlate highest with its neighbors in the model and the lower the farther away a scale is in the model; a scale should correlate highly negative with the scale opposite in the model. For the first version of the QSDI, six items per scale were formulated depicting different supervisor behaviors. These items were developed from the existing items used in secondary schools or teacher education. For example the item “my supervisor says that I am unskilled” emerged from the secondary item “this teacher says we do not perform well.” Items are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never/not at all’ to ‘always/very’. This early version was administered to 25 PhD students in the field of social sciences. Results were tested for circumplex structure (factor analyses and scale correlations) and scale reliabilities (Cronbach’s α). After additional adaptations a 48-item version of the QSDI was crafted. Subsequently, this version was administered to a larger sample of doctoral students.

To verify the concurrent validity of the QSDI, a modified version of the postgraduate research experience questionnaire (PREQ; Marsh et al. 2002 ) was administered to the target group alongside the QSDI. The PREQ was developed in a project of the Australian Council for Educational Research ( 1999 ) in a thorough process of literature review, analyses of good practice, institutional evaluation, and involving existing instruments. In several steps the questionnaire evolved to a form further investigated by Marsh et al. ( 2002 ). The PREQ appeared not to be useful to compare institutions but is a valuable measurement instrument for perceptions of individual students with good content and face validity and good psychometric characteristics such as the factor structure and scale reliability. The PREQ can be used to evaluate individual student’s experience of their PhD period in retrospect. It consists of six scales called ‘Supervision’, ‘Skill development’, ‘Climate’, ‘Infrastructure’, ‘Thesis examination’, and ‘Clarity’. Items were originally answered on an agree–disagree scale. We chose to use a five-point Likert scale ‘never/not at all’ and ‘always/very’ for the sake of uniformity of the combined QSDI–PREQ questionnaire. Because the current sample consisted of PhD students who were still working on their doctorate, our version was formulated in present rather than past tense. In addition, the ‘Thesis examination’ scale was excluded.

Finally, various doctoral student background characteristics (age, gender, and time spent on the project), gender of the supervisor, and the setting (meeting hours per week) were included. The questionnaire was administered online in English.

In total 155 members of the PhD division of the Netherlands Educational Research Association were invited by mail for participation; 98 questionnaires were completed. Of the remaining 57, 24 persons reported that they had received their doctorate already and thus had been invited erroneously. An additional 33 emails remained unreplied. Thus, the effective response ratio may be estimated to be 75%. Of the 98 participants 33% were male and 67% female; 54% were between 25 and 30 years old. Although a few students might have answered the questionnaire about the same supervisor most of the students will have had a different supervisor.

Reliability and internal validity of the QSDI

As mentioned above, the eight QSDI scales should be ordered on a circumplex. An important assumption of circumplex models is that correlations between scales are getting smaller as a function of the distance between scales and that a scale correlates highest negatively with its opposite scale. The 48 items version of the QSDI did not completely satisfactory show this correlation structure. Therefore, from four scales a total of seven items were removed. Thus the final version of the QSDI consisting of 41 items emerged (see Table 5 ).

The reliabilities (Cronbach’s α’s) of the eight resulting scales ranged between .70 and .87 (see Table 1 ) which is considered to be satisfactory to good.

Table 2 shows the correlations between the different scales of the QSDI. The circumplex assumption is only slightly violated with reference to the CD scale: the SO and OD scales showed greater negative correlations with the CD scale (−.69 and −.73, respectively) instead of the theoretically to be expected OS scale (−.66). Similarly, this disrupted correlation pattern led to a disturbance of the correlation pattern of the SC scale. In our sample SC showed the greatest negative correlation with the OD scale instead of the theoretically to be expected DO scale (−.52 and −.34, respectively).

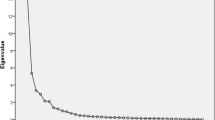

Factor analyses showed that indeed two dimensions underlie the eight scales, and that the scales do follow each other in the correct order (Fig. 2 ). However, the scales are not evenly distributed over the circle. Because the two dimensions Influence and Proximity are supposed to be orthogonal the correlation between the two factors should be low. The actual correlation is 0.30, which is a bit higher than expected.

Results of factor analysis on the eight scales: rotated solution for two factors explaining 75% of the total variance

Concurrent validity of the QSDI

The α coefficients in the current sample for the PREQ ranged from .84 to .91 (see Table 3 ).

Although the QSDI and PREQ do not have the same aspiration with regard to the underlying constructs the questionnaires aim to measure, the QSDI might be understood as a further elaboration of the supervisor-scale of the PREQ. In order to investigate the concurrent validity correlations were calculated between the Influence and Proximity dimensions of the QSDI and the scales of the PREQ. In case of a satisfactory concurrent validity high correlations should be found between Influence and Proximity of the QSDI and the supervisor-scale, and the correlation pattern of the supervisor-scale with the other scales of the PREQ should resemble the pattern of the Influence and Proximity dimensions. The correlation matrix is provided in Table 4 .

As expected the highest correlations were found between the supervisor-scale of the PREQ and Influence and Proximity (.58 and .66, respectively). Influence and Proximity followed the general correlation pattern of the PREQ except of small differences for two correlations. The correlations between Influence and the climate scale (.30) was slightly lower than with the infrastructure scale (.35), and slightly higher that with the clarity scale (.29). Marsh et al. ( 2002 ) mention the supervisor and skill development scales as the ones most prominent connected to the supervisors’ role. They argue that the climate, infrastructure and clarity scales in addition include perceptions related to the academic unit and the entire university. This might explain lower correlations of the supervisor–doctoral student relationships with the last three scales.

Average profile

The scores for the perceptions of a specific doctoral student about his or her supervisor can be displayed in the model shown in Fig. 1 : the profile of a supervisor according to the particular student. As an example, the average profile in the data collected in this study is presented in Fig. 3 .

Average profile collected from doctoral students about theirs supervisors in this study ( n = 96)

This graph shows that the supervisors in our sample are on average seen as displaying rather much leadership, helping/friendly, understanding behavior and providing a lot of student freedom an responsibility. They do not show a lot of uncertain, dissatisfied or admonishing behavior and the amount of strict behavior is moderate.

Correlational analyses showed that most background characteristics measured were not associated with the scores on dimensions or scales. Only for the Influence dimension two significant, but small correlations were found: supervisor gender correlated .24, and the number of meeting hours with the supervisor .31 with the Influence dimension. Female supervisors were seen more influential than male supervisors, and the more hours doctoral student and supervisor were meeting a week the more influential the student saw the supervisor.

Conclusion and discussion

Considering the Cronbach’s α’s of the eight scales in this study, the QSDI appeared to be a reliable instrument to gather data about doctoral students’ perceptions of their supervisor’s interpersonal style in the relationship with a particular student. The validity in terms of representing a circumplex model was reasonable but the scales were not evenly distributed on the circumplex. Comparison of the QSDI with the supervisor scale of the postgraduate research experience questionnaire showed the concurrent validity of the QSDI to be good.

The QSDI is an instrument that can be used to study the relationship between supervisors and their doctoral students. Research questions about this relationship are open to investigation with the QSDI in combination with instruments to measure other variables. One can study for example what supervisory styles are most effective in terms of length of doctoral studies, doctoral student’s satisfaction with the supervision or quality of dissertations. When combined with measuring doctoral students’ characteristics positive alignments of supervisory style with doctoral students can be sought. In learning environments research an important line of study includes two versions of student questionnaires: one asking for the preferred and the other for the actual experienced environment (cf. Fraser 1991 ). For doctoral supervision employing the QSDI in these two versions might reveal doctoral students’ preferences for supervision styles and combinations with preferences of supervisors and their actual styles can be studied. Finally, the QSDI can help evaluate interventions to improve supervisory relationships.

The QSDI can be used to provide supervisors with feedback about their interpersonal style with the aim to improve the quality of their supervision. Although communication between supervisor and doctoral student often will be so open that no data from a questionnaire are needed, using this questionnaire offers a framework to discuss the relationship and the data will add insights that not always will come to the fore in an unstructured discussion between supervisor and doctoral student. For a quick indication of the quality of the supervisor–doctoral student relationship sector scores can be used, and on a more detailed level scores on individual items may be utilized. By using actual and preferred forms of the QSDI discrepancies between situations strived for and what is accomplished can be brought to the surface, thus providing an avenue for improvement, and a basis for discussing supervision. Similarly, for the candidates such an assessment at the beginning of the project might help articulating what he or she wants from a supervisor. Thus, the QSDI can be used in the matching process when actual supervisors’ styles and preferred styles of students are known.

In addition to doctoral student’s perceptions, also supervisors’ perceptions of their own style and their preferred style can be collected by asking the supervisor to answer the questionnaire for this purpose. The sector scores conveniently can be displayed in the model both for doctoral student and supervisor perceptions (see Fig. 4 for an example).

Example of supervisor ideal, supervisor self perception and doctoral student perception

Several studies have shown that students’ feedback on instructors’ performance may have positive effects on an instructors’ teaching (see for a review Marsh and Dunkin 1997 ; Marsh and Roche 1993 ). Appropriate consultation strengthens this effect. Experiences with the QTI with teachers at the primary and secondary level are promising (Scott et al. 2003 ; Derksen 1995 ).With the QSDI we have some positive experience as a feedback instrument but no formal research study has been conducted until now. As has been shown for teacher’s feedback for students, important conditions must be met to make feedback supportive (Hattie and Timperley 2007 ). Such conditions are a good climate, thorough knowledge of the teacher of the content area, and an emphasis rather on the task than on the person. Important ingredients for an effective strategy to improve supervision based on students’ feedback probably are specific feedback, concrete suggestions for improvement and involvement of a trained consultant (Marsh et al. 2002 ). Through the items included, the QSDI gives ample opportunity to provide such concrete, specific information about aspects of the behavior that might need improvement. It gives for example a more differentiated view than the four styles distinguished by Gatfield ( 2005 ).

Several tenets of the model for interpersonal supervisor behavior seem important when the model is used for the purpose of coaching supervisors of PhD candidates. First, it is important to remember that the two dimensions of the model are independent. In our experience supervisors often assume that showing behavior that is high on the Influence dimension implies to be also a bit to the left on the Proximity dimension. Similarly they tend to combine high Proximity with low Influence behavior. This, however, is not necessary: high Influence as well as low Influence behaviors may go together with behaviors that are high or low on Proximity. As mentioned above, a supervisor for example may provide guidance either by setting strict rules solely based on his/her own experience (high Influence, somewhat opposition) or by anticipating on or adapting to the student’s wishes (high Influence, somewhat cooperation). Keeping this in mind might be helpful for supervisors.

Second, behaviors that are situated opposite to each other in the model are the most difficult to combine. For example, the tension that was mentioned in the section on supervisory problems in this paper between guidance and assessment is in the model reflected by the opposite position of the dissatisfied and helpful/friendly sectors. A supervisor must both be able to support a PhD student and display dissatisfaction when a product of the student does not meet the required standards. It might help to make supervisors aware of this opposite position and the need to learn to combine these behaviors productively, or to become flexible in their use in different situations.

Third, the concept of self reinforcing processes is important (Wubbels et al. 1988 ). In relationships between teachers and students different principles apply for the Influence and Proximity dimensions. Behaviors of participants associated with the Influence dimension tend to evoke opposite behaviors (i.e., reciprocity): for example, the more a supervisor might provide structure, the more a student might become dependent on the supervisor. For the Proximity dimension another process is involved (i.e., complementarity): behaviors on this dimension tend to evoke similar behavior of the other participant; the more friendliness the supervisor expresses, the more friendliness the student will show. Similarly, hostile behavior of the supervisor is likely to invoke hostility from the PhD student.

In conclusion, the QSDI can be used both as a research and as a feedback instrument. It can contribute to solving the three supervisory problems mentioned in the introduction of this paper. First, the opposite placement of helping/friendly and dissatisfied behavior in the model helps clarify the tension between guidance and assessment in the supervisory process. Second, analyzing doctoral student’s preferred style and the supervisor’s ideal may help in the matching of PhD candidates and supervisors. Finally, the use of the QSDI for feedback will help to strengthen or to create a climate in research institutes where evaluation of doctoral student’s experiences is common practice.

The QSDI maps the relationship between a doctoral student and his or her supervisor from the perspective of the student. For future research it could be interesting to complement this view with the supervisor’s perception of the student’s style. Kam ( 1997 ) for example showed the importance of a student’s tendency to rely on the supervisor is important in shaping the relationship.

Anderson, M. S., & Seashore-Louis, K. (1994). The graduate student experience and subscription to the norms of science. Research in Higher Education, 35 (3), 273–299. doi: 10.1007/BF02496825 .

Article Google Scholar

Australian Council for Educational Research. (1999). Evaluation and validation of the trial postgraduate research experience questionnaires . Camberwell: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Google Scholar

Bell-Ellison, B. A., & Dedrick, R. F. (2008). What do doctoral students value in their ideal mentor? Research in Higher Education, 49 (6), 555–567.

Braskamp, L. A., & Ory, J. C. (1994). Assessing faculty work: Enhancing individual and institutional performance . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cashin, W. E., & Downey, R. G. (1992). Using global student ratings for summative evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84 (4), 563–572.

d’Apollonia, S., & Abrami, P. C. (1997). Navigating student ratings of instruction. American Psychologist, 52 (11), 1198–1208.

Denicolo, P. (2004). Doctoral supervision of colleagues: Peeling off the veneer of satisfaction and competence. Studies in Higher Education, 29 (6), 693–707.

Derksen, K. (1995). Activating instruction: The effects of a teacher-training programme . Paper presented at the 6th conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction, Nijmegen.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11 (2), 77–83.

Fraser, B. J. (1991). Two decades of classroom environment research. In B. J. Fraser & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Educational environments (pp. 3–27). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Gatfield, T. (2005). An investigation into PhD supervisory management styles: Development of a dynamic conceptual model and its managerial implications. Journal of Higher Education Policy and management, 27 (3), 311–325.

Golde, C. M. (2000). Should I stay or should I go? Student descriptions of the doctoral attrition process. The Review of Higher Education, 23 (2), 199–227.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77 (1), 81–112.

Heath, T. (2002). A quantitative analysis of PhD students’ views of supervision. Higher Education Research & Development, 21 (1), 41–53.

Hockey, J. (1996). A contractual solution to problems in the supervision of PhD degrees in the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 21 (3), 359–371.

Holligan, C. (2005). Fact and fiction: A case history of doctoral supervision. Educational Research, 47 (3), 267–278.

Ives, G., & Rowley, G. (2005). Supervisor selection or allocation and continuity of supervision: PhD students’ progress and outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 30 (5), 535–555.

Judd, C. M., James-Hawkins, L., Yzerbyt, V., & Kashima, Y. (2005). Fundamental dimensions of social judgment: Understanding the relations between judgments of competence and warmth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89 (6), 899–913.

Kam, B. H. (1997). Style and quality in research supervision: The supervisor dependency factor. Higher Education, 34 (1), 81–103.

Kremer-Hayon, L., & Wubbels, T. (1993a). Supervisors’ interpersonal behavior and student teachers’ satisfaction. In T. Wubbels & J. Levy (Eds.), Do you know what you look like?: Interpersonal relationships in education (pp. 123–135). London: The Falmer Press.

Kremer-Hayon, L., & Wubbels, T. (1993b). Principals’ interpersonal behavior and teachers’ satisfaction. In T. Wubbels & J. Levy (Eds.), Do you know what you look like?: Interpersonal relationships in education (pp. 113–122). London: The Falmer Press.

Leary, T. (1957). An interpersonal diagnoses of personality . New York, NY: The Ronald Press Company.

Leonard, D., Metcalfe, J., Becker, R., & Evans, J. (2006). Review of literature on the impact of working context and support on the postgraduate research student learning experience . New York, NY: The Higher Education Academy.

Li, S., & Seale, C. (2007). Managing criticism in PhD supervision: A qualitative case study. Studies in Higher Education, 32 (4), 511–526.

Lindén, J. (1999). The contribution of narrative to the process of supervising PhD students. Studies in Higher Education, 24 (3), 351–369.

Luna, G., & Cullen, D. (1998). Do graduate students need mentoring? College Student Journal, 32 (3), 322–330.

Marsh, H. W., & Dunkin, M. (1997). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: A multidimensional perspective. In R. P. Perry & J. C. Smart (Eds.), Effective teaching in higher education: Research and practice (pp. 241–320). New York, NY: Agathon.

Marsh, H. W., & Roche, L. A. (1993). The use of students’ evaluations and an individually structured intervention to enhance university teaching effectiveness. American Educational Research Journal, 30 (1), 217–251.

Marsh, H. W., & Roche, L. A. (1997). Making students’ evaluations of teaching effectiveness effective. American Psychologist, 52 (11), 1187–1197.

Marsh, H. W., Rowe, K. J., & Martin, A. (2002). PhD students’ evaluations of research supervision. The Journal of Higher Education, 73 (3), 313–348.

McAlpine, L., & Norton, J. (2006). Reframing out approach to doctoral programs: An integrative framework for action and research. Higher Education Research & Development, 25 (1), 3–17.

Murphy, N., Bain, J. D., & Conrad, L. M. (2007). Orientations to research higher degree supervision. Higher Education, 53 (2), 209–234.

Nelson, M. L., & Friedlander, M. L. (2001). A close look at conflictual supervisory relationships: The trainee’s perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48 (4), 384–395.

Paglis, L. L., Green, S. G., & Bauer, T. N. (2006). Does adviser mentoring add value? A longitudinal study of mentoring and doctoral student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 47 (4), 451–476.

Pearson, M. (1996). Professionalising PhD education to enhance the quality of the student experience. Higher Education, 32 (3), 303–320.

Rose, G. L. (2003). Enhancement of mentor selection using the ideal mentor scale. Research in Higher Education, 44 (4), 473–494.

Rose, G. L. (2005). Group differences in graduate students’ concepts of the ideal mentor. Research in Higher Education, 46 (1), 53–79.

Scott, R., Fisher, D., & den Brok, P. (2003). Specialist science teachers’ classroom behaviors in 12 primary schools . Paper presented at the annual conference of the European Science Education Research Association, Noordwijkerhout.

Seagram, B. C., Gould, J., & Pyke, W. (1998). An investigation of gender and other variables on time to completion of doctoral degrees. Research in Higher Education, 39 (3), 319–335.

Shuell, T. J. (1996). Teaching and learning in a classroom context. In D. C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 726–763). New York, NY: MacMillan.

Sinclair, M. (2004). The pedagogy of ‘good’ PhD supervision: A national cross-disciplinary investigation of PhD supervision . Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Education, Science and Training.

Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. H., & Jackson, D. D. (1967). The pragmatics of human communication . New York, NY: Norton.

Wubbels, T., Créton, H., & Holvast, A. J. C. D. (1988). Undesirable classroom situations. Interchange, 19 (2), 25–40.

Wubbels, T., Brekelmans, M., den Brok, P., & van Tartwijk, J. (2006). An interpersonal perspective on classroom management in secondary classrooms in the Netherlands. In C. Evertson & C. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues (pp. 1161–1191). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Download references

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Tim Mainhard, Roeland van der Rijst, Jan van Tartwijk & Theo Wubbels

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Theo Wubbels .

See Table 5 .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mainhard, T., van der Rijst, R., van Tartwijk, J. et al. A model for the supervisor–doctoral student relationship. High Educ 58 , 359–373 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9199-8

Download citation

Received : 21 July 2008

Accepted : 17 January 2009

Published : 05 February 2009

Issue Date : September 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9199-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- PhD supervision

- Doctoral student

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

PhD supervisor-student relationship

Filipe prazeres.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: Filipe Prazeres, Family Health Unit Beira Ria, Rua Padre Rúbens, 3830-596 Gafanha da Nazaré, Portugal Tel: +351234393150

E-mail : [email protected]

Accepted 2017 Aug 9; Received 2017 Jun 22.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

To the Editor,

The relationship between the PhD supervisor and the PhD student is a complex one. When this relationship is neither effective nor efficient, it may yield negative consequences, such as academic failure ( 1 ).

The intricacy of the supervisor-student relationship may be in part comparable to the one between the physician and his/her patient [see, for example ( 2 )]. Both interactions develop over several years and the players involved in each relationship - PhD supervisor-student on the one side and physician-patient on the other side - may at some point of the journey develop different expectations of one another [see, for example ( 3 , 4 )] and experience emotional distress ( 5 ). In both relationships, the perceived satisfaction with the interaction will contribute to the success or failure of the treatment in one case, and in the other, the writing of a thesis. To improve the mentioned satisfaction, not only there is a need to invest time ( 6 ), as does the physician to his/her patients, but also both the supervisor and the PhD student must be willing to negotiate a research path to follow that would be practical and achievable. The communication between the physician and patient is of paramount importance for the provision of health care ( 7 ), and so is the communication between the supervisor and PhD student which encourages the progression of both the research and the doctoral study ( 8 ).

As to a smooth transition to the postgraduate life, supervisors should start thinking about providing the same kind of positive reinforcement that every student is used to experience in the undergraduate course. The recognition for a job well done will mean a lot for a PhD student, as it does for a patient. Onegood example is the increase in medication compliance by patients with high blood pressure who receive positive reinforcement from their physicians ( 9 ).

Supervisors can organize regular meetings for (and with) PhD students in order to not only discuss their projects but also improve their coping skills, including critical thinking and problem-solving methods ( 5 ). The act of sharingknowledge and experiences can motivate the PhD students to persevere in their studies ( 10 ).

When needed, supervisors should use their power of influence to increase the time that the student has available to devote to research while maintaining a part of their employment activities (healthcare-related or not), since many PhD students are also full-time workers.

Last but not least, supervisors and faculty membersmust encourage PhD students to pursue the available funding opportunities. Socioeconomic problems are known to be an issue for PhD students ( 5 ). Without the supervisor’s support - by dealing with PhD student’s emotions and personality -, research time, funding, and the student’s proactiviness, the doctoral journey may not attainsuccess.

Conflict of interests: there is no conflict of interest.

- 1. Diamandis E. A growing phobia. Nature. 2017;544: 129. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Goold SD, Lipkin M. The doctor-patient relationship. Journal of general internal medicine. 1999;14: S26–S33. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00267.x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Gill P, Burnard P. The student-supervisor relationship in the phD/Doctoral process. British Journal of Nursing. 2008;17: 668–71. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.10.29484. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Mainhard T, van der Rijst R, van Tartwijk J, Wubbels T. A model for the supervisor–doctoral student relationship. Higher Education. 2009;58: 359–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Bazrafkan L, Shokrpour N, Yousefi A, Yamani N. Management of Stress and Anxiety Among PhD Students During Thesis Writing: A Qualitative Study. The health care manager. 2016;35: 231–40. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000120. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. McDonald DA. PhD supervisors: invest more time. Nature. 2017;545: 158. doi: 10.1038/545158b. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. The Ochsner journal. 2010;10: 38–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Yarwood-Ross L, Haigh C. As others see us: what PhD students say about supervisors. Nurse Researcher. 2014;22: 38–43. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.1.38.e1274. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, Allegrante JP, Isen AM, Jobe JB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172: 322–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. McCarthy G, Hegarty J, Savage E, Fitzpatrick JJ. PhD Away Days: a component of PhD supervision. International Nursing Review. 2010;57: 415–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00828.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PDF (317.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

PhD supervisors tend to fulfil several functions: the teacher; the mentor who can support and facilitate the emotional processes; and the patron who manages the springboard from which the...

In this post, we consider the main features that contribute to a thriving and productive collaboration between supervisors and their PhD students. Clear Communication: Effective communication is the cornerstone of any successful relationship, and the supervisor-PhD student dynamic is no exception.

This chapter explores the PhD Student-Supervisor relationship, outlining the role of a PhD Supervisor, discussing relationship management, and how to recognise signs of bullying and harassment if they occur.

This paper describes the development of the questionnaire on supervisor–doctoral student interaction (QSDI). This questionnaire aims at gathering information about doctoral students’ perceptions of the interpersonal style of their supervisor. The QSDI appeared to be a reliable and valid instrument.

The relationship between the PhD supervisor and the PhD student is a complex one. When this relationship is neither effective nor efficient, it may yield negative consequences, such as academic failure .

Our study investigates the relational processes and their effects in PhD student–supervisor relationships, with a particular focus on the factors affecting students’ motivation and well-being in supervision panels where students have multiple supervisors.

The relationship between students and supervisors is vital to successful PhD completion, and this study has provided some of the experiences students share with each other in an online ...

For a PhD student, the value of a supervisor is the ability to receive advice and recommendations and continuously. A PhD student should, using the opportunity available to him, “exploit” the methodical erudition, knowledge, and experience of his supervisor, and not hope that he will pull him out to defend his dissertation.

A successful relationship between PhD students and their supervisor is built on trust, communication, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the student's academic growth.

PhD supervision is associated with a variety of expectations and responsibilities, from both the student and the supervisor, but there is also not a single approach to the supervisor relationship.