Advertisement

Diversity in the Classrooms: A Human-Centered Approach to Schools

- Published: 17 April 2020

- Volume 51 , pages 429–439, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Daniela Fontenelle-Tereshchuk 1 , 2

3291 Accesses

6 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article explores the perceptions of experiences and insights of four Alberta teachers on the understanding of diversity in the classrooms. The teachers in this multiple case study argue that the popular understanding of diversity, especially in schools, is often supported by American contextualized narrative of polarized racial views focusing on assumptions of contrasting ‘whiteness’ visible in race, culture and socio-economic status associated to ones’ skin colour, for instance it recognizes dark-skinned students as diverse as opposed to teachers who are perceived simply as a large group of ‘white, middle-class ladies’. Such conceptualization of diversity is problematic as its social-constructed understanding implies that teachers of European descent share a common ‘Euro-centered’ history, culture, and ethnicity, while Europe is in fact an ethnically, historically and culturally diverse continent. These assumptions have serious implications on teaching and learning as it directly reflects on teacher preparation programs, professional development practices and educational policies. The selective approach to diversity based on race and culture does a disservice to education’s purpose as it over-focuses on visible aspects of differences among students while it disregards the universal needs of a community of learners in schools. This paper advocates for a human-centered understanding of diversity in schools, which seeks to understand diversity beyond the socially constructed borders surrounding race, culture and gender, often used to define teachers as simply ‘white’ in the context of diversity in Canada.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Who Are the Teachers and Who Are the Learners? Teacher Education for Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Preparing Teachers for Diversity and Inclusion: An Analysis of Teacher Education Policies and Practices in Austria

Racialized Identity: (In)Visibility and Teaching—A Community of Critical Consciousness

Alberta Education (2010). Making a difference: Meeting diverse learning needs with differentiated instruction . Retrieved from https://education.alberta.ca/media/384968/makingadifference_2010.pdf

Aoki, T. T. (2005) Toward curriculum inquiry in a new key (1978/1980). In Aoki, T. T., Pinar, W. F., Irwin, R. L., & Ebrary, I. Curriculum in a new key: The collected works of Ted T. Aoki . Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum.

ATA -Alberta Teachers Association (2014). Report of the blue ribbon panel: Inclusive education in Alberta school . Retrieved from https://www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/News-Room/2014/PD-170-1%20PD%20Blue%20Ribbon%20Panel%20Report%202014-web.pdf

ATA -Alberta Teachers Association (2009). Mental health in Schools: Teachers have the power to make a difference . Edmonton, Canada. Retrieved from https://www.teachers.ab.ca/Publications/ATA%20Magazine/Volume%2090/Number%201/Articles/Pages/MentalHealthinSchools.aspx

Banks, J. A., & Banks, C. A. M. (2004). Handbook of research on multiculturalism education (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Google Scholar

Bhabha, H. (1994). The location of culture . New York, NY: Routledge.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Courtland, M. C., & Gonzalez, I. (2013). Imagining the possibilities: The potential of diverse Canadian picture books. In I. Johnston & J. Bainbridge (Eds.), The pedagogical potential of diverse Canadian picture books: Pre-service teachers explore issues of identity, ideology, and pedagogy (pp. 96–113). Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto.

Cranston, A. J. (2015). Navigating the Bermuda Triangle of teacher hiring practices. In N. Maynes & B. E. Hatt (Eds.), Canada the complexity of hiring, supporting, and retaining new teachers across Canada (pp. 128–149). Polygraph Series: Canadian Association for Teacher Education (CATE).

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th Ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design (international student edition): Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crocker, R. K., & Dibbon, D. C. (2008). Teacher education in Canada: A baseline study. Society for the Advancement of Excellence in Education. Kelowna, Canada: University of Calgary. Retrieved from https://deslibris.ca/ID/216529

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fontenelle-Tereshchuk, D. D. (2019). Exploring teachers' insights into their professional growth and other experiences in diverse classrooms in Alberta. University of Alberta, Canada. Doctoral unpublished dissertation.

Gérin-Lajoie, D. (2012). Racial and ethnic diversity in schools: The case of English Canada. Prospects, 42 (2), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-012-9231-0 .

Article Google Scholar

Gérin-Lajoie, D. (2008). Educators' discourses on student diversity in Canada: Context, policy, and practice . Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine. Retrieved from https://www.sxf.uevora.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Glaser_1967.pdf

Guess, T. J. (2006). The social construction of whiteness: Racism by intent, racism by consequence. Critical Sociology, 32 (4), 649–673. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916306779155199 .

Guo, Y. (2011). Perspectives of immigrant Muslim parents: Advocating for religious diversity in Canadian schools. (Researching bias). Multicultural Education, 18 (2), 55–60.

Howe, E. (2014). Bridging the aboriginal education gap in Alberta: The provincial benefit exceeds a quarter of a trillion dollars. Rupertsland Centre for Métis Research .

McLaren, P. (1994). Life in schools : An introduction to critical pedagogy in the foundations of education (2nd ed.). Toronto, Canada: Irwin.

McLeod, K. (1975). Education and the assimilation of new Canadians in the North-West territories and Saskatchewan1885–1934 . University of Toronto, Canada. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation).

Miller, J. (2018). Residential Schools in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools

Milner, H. R. (2010). What does teacher education have to do with teaching? Implications for diversity studies. Journal of Teacher Education, 61 (1–2), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347670 .

Moore, A. (2004). The good teacher: Dominant discourses in teaching and teacher education . New York, NY: Routledge Falmer.

Book Google Scholar

Padula, A. P., & Miller, L. D. (1999). Understanding Graduate Women's Re-entry Experiences: Case Studies of Four Psychology Doctoral Students in a Midwestern University. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23 , 327–343.

Palmer, H. (1982). Patterns of prejudice: A history of nativism in Alberta . Toronto, Canada: McClelland and Stewart.

Peacock J., Holland D., (1993) The Narrated Self Life Stories in Process. Ethos 21(4): 367–383

Rodrigues, S. (2005). Teacher professional development in science education . In S. Rodrigues, International perspectives on teacher professional development: Changes influenced by politics, pedagogy and innovation (pp.1 13). New York, NY: Nova Science

Ryan, J., Pollock, K., & Antonelli, F. (2009). Teacher diversity in Canada: Leaky pipelines, bottlenecks, and glass ceilings. Canadian Journal of Education, 32 (3), 591–617.

Syed, K. T. (2010). Canadian educators’ narratives of teaching multicultural education. International Journal of Canadian Studie s, 42, 255–269. Retrieved from https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ijcs/2010-n42-ijcs1516360/1002181ar.pdf

Statistics Canada (2017). Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98–404-X2016001. Ottawa, Ontario. Data products, 2016 Census. Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-pr-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&GK=PR&GC=48&TOPIC=7

U.S. National Library of Medicine (2019). Help me understand genetics: Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing. Retrieved from PDF version of https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/dtcgenetictesting/ancestrytesting .

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Secondary Education, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

Daniela Fontenelle-Tereshchuk

Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniela Fontenelle-Tereshchuk .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Fontenelle-Tereshchuk, D. Diversity in the Classrooms: A Human-Centered Approach to Schools. Interchange 51 , 429–439 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-020-09402-4

Download citation

Received : 03 January 2020

Accepted : 08 April 2020

Published : 17 April 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-020-09402-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Diversity Interventions in the Classroom: From Resistance to Action

Dustin b thoman, melo-jean yap, felisha a herrera, jessi l smith.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*Address correspondence to: Dustin B. Thoman ( [email protected] ).

Received 2020 Jul 13; Revised 2021 Jun 22; Accepted 2021 Jul 23.

This article is distributed by The American Society for Cell Biology under license from the author(s). It is available to the public under an Attribution–Noncommercial–Share Alike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons License.

What goes into faculty decisions to adopt a classroom intervention that closes achievement gaps? We present a theoretical model for understanding possible resistance to and support for implementing and sustaining a diversity-enhancing classroom intervention. We propose, examine, and refine a “diversity interventions—resistance to action” model with four key inputs that help explain faculty’s decision to implement (or not) an evidence-based intervention: 1) notice that underrepresentation is a problem, 2) interpret underrepresentation as needing immediate action, 3) assume responsibility, and 4) know how to help. Using an embedded mixed-methods design, we worked with a sample of 40 biology faculty from across the United States who participated in in-depth, semistructured, qualitative interviews and surveys. Survey results offer initial support for the model, showing that the inputs are associated with faculty’s perceived value of and implementation intentions for a diversity-enhancing classroom intervention. Findings from qualitative narratives provide rich contextual information that illuminates how faculty think about diversity and classroom interventions. The diversity interventions—resistance to action model highlights the explicit role of faculty as systemic gatekeepers in field-wide efforts to diversify biology education, and findings point to strategies for overcoming different aspects of faculty resistance in order to scale up diversity-enhancing classroom interventions.

DIVERSITY INTERVENTIONS IN THE CLASSROOM: FROM RESISTANCE TO ACTION

Broadening participation in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) research workforce necessarily means cultivating the next generation of researchers. It is essential to create a learning and working research context that is inclusive and diverse, where historically oppressed voices, ways of knowing, and lived experiences shape research and discovery. This is why supporting efforts to diversify the U.S. STEM workforce is a long-standing mission of national scientific agencies, including the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and National Academies. Consistently tracking data to identify group-based inequalities in participation and degree attainment (e.g., differences between majority and historically underrepresented minority [URM] students) is an essential first step in identifying the problem ( National Center for Education Statistics, 2019 ). Developing and rigorously testing theoretically informed strategies to reduce inequities is a critical second step. What is also clear from national priorities and reports is the need for sustainability and achieving scale for empirically supported strategies. But this is easier said than done and requires trying to understand psychological and social interventions “that mitigate … barriers to workforce diversity” with the need to have “a national strategy to scale, disseminate and sustain” diversity-enhancing intervention efforts ( Valantine and Collins, 2015 , p. 12240).

There are many examples of evidence-based diversity-enhancing interventions that can provide scalable solutions that address inequities. Indeed, researchers have developed a wide range of simple, low-cost interventions for undergraduate classrooms that aim to change the educational environment (versus “fixing” the underrepresented student) with demonstrated long-lasting effects for closing achievement gaps and broadening participation ( Fox et al. , 2009 ; Tibbetts et al. , 2016 ; Casad et al. , 2018 ). We refer to these as “diversity-enhancing interventions.”

Despite the promise of such low-cost evidence-based curricular interventions for shrinking achievement gaps in biology courses, and STEM courses more broadly, they are not always—or even often—adopted outside the study context (e.g., Austin, 2011 ; Kezar et al. , 2015 ). In this paper, we consider why successful diversity-enhancing classroom interventions are not more often adopted. We first describe what we mean by diversity-enhancing interventions and present our diversity interventions—resistance to action model. We then present mixed-methods data to 1) examine the potential for our model to explain instructors’ decisions related to diversity-enhancing interventions and 2) conduct an initial exploration of how faculty think about diversity in general and diversity-enhancing interventions in particular.

To provide a concrete example in biology education, we consider the utility value intervention (UVI) as our exemplar intervention. In a randomized control trial study conducted at the University of Wisconsin ( Harackiewicz et al. , 2016 ), students ( n = 1040) wrote essays about course content at three points during the semester and discussed how the topic was relevant to their own lives (in control conditions, students wrote summaries of course content only). The UVI had a positive effect for all students in the biology class and was most effective for students with lower prior grade point averages, replicating previous work ( Hulleman and Harackiewicz, 2009 ; Hulleman et al. , 2010 ). Further, it proved to be effective for URM students and particularly effective in improving course grades (by ∼0.5 grade points) for students who were both first-generation (FG) college students (neither parent earned a 4-year degree) and URM, reducing the achievement gap for FG-URM students by 61%. Beyond grades, students who wrote the utility value essays reported greater interest in biology and were more likely to continue to the second course in the biology sequence and persist in their STEM majors than students who did not write utility value essays ( Canning et al. , 2018 ).

What happens after successful findings such as these are published? Faculty not involved in the initial intervention testing phase rarely adopt novel interventions, despite the multiple dissemination outlets, publicity, and professional associations that emphasize adopting evidence-based practices (e.g., Gess-Newsome et al. , 2003 ; Henderson et al. , 2011; Andrews and Lemons, 2015 ). There are multiple points in the process between publication of findings and broad implementation where barriers may exist. Getting findings and implementation guides into the hands of faculty can be difficult, for example. But even when faculty get such information, they often decide not to implement the new practice in their own classes, and the aim of our work is to systemically study this decision-making process.

What does it take to get faculty to adopt a diversity-enhancing intervention (e.g., the UVI or others) in their classrooms? What obstacles arise? What strategies facilitate faculty’s willingness to intervene in their classrooms to diversify the science workforce? Faculty are principal change agents in higher education ( Beale et al. , 2013 ; Kezar et al. , 2015 ), so answering these questions is a critical next step in intervention research. We must better understand the intervention implementation process ; if we do not, we risk failing at scaling up and sustaining diversity-enhancing interventions.

Diversity Intervention—Resistance to Action Model

We draw on organizational theories of diversity resistance and social psychological theories of decision making to inform a model for predicting and understanding possible resistance to and support for implementing and sustaining a diversity-enhancing classroom intervention. Framing intervention implementation as a “helping action” leads us to use Thomas and Plaut’s ( 2008 ) inspired adaption of Latané and Darley’s ( 1970 ) decision model of helping. Latané and Darley developed their classic social psychological model of helping to describe why people sometimes do (and do not) help others in emergency situations. Theirs was the first model to highlight the importance of social cues serving as information; when the situation is ambiguous, people look to others to determine whether the situation is, in fact, an emergency and whether their personal action is required. They coined the terms “bystander effect” and “diffusion of responsibility” to describe the situation when no individual among a group helps someone in need because they do not interpret the event as an emergency, do not see anyone else helping, assume someone else will help, or they are not sure how to help ( Darley and Latane, 1968 ). Following Thomas and Plaut (2008) , we conceptualize implementing a diversity intervention as a “helping” action and articulate an inspired process model of social cognitive inputs that delineates similar decision steps that lead to faculty deciding to take action and implement a diversity-enhancing intervention in their classes. We further expected that several social psychological factors, derived from the bystander intervention research, would function as barriers to “helping” and reduce the likelihood of intervention implementation.

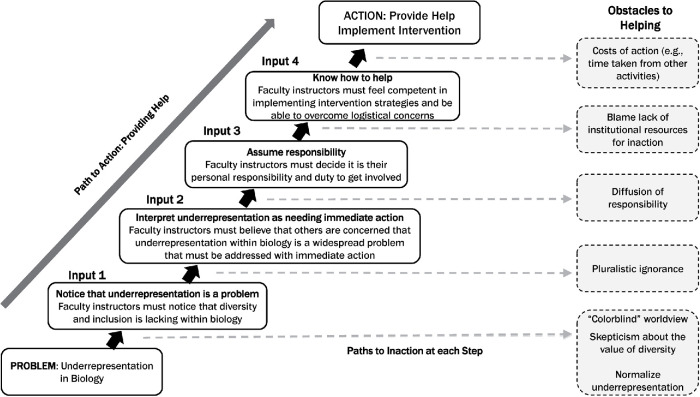

Our diversity intervention—resistance to action model adopts the key inputs from Latane and Darley’s model of helping to understand faculty’s decision to implement (or not) an evidence-based diversity-enhancing intervention, as follows: 1) notice that underrepresentation is a problem, 2) interpret underrepresentation as needing immediate action, 3) assume responsibility, and 4) know how to help. We detail each input in the sections below. Figure 1 illustrates the model, starting at the bottom with noticing the problem of underrepresentation in biology, with decision inputs along the left of the figure and obstacles to helping on the right. The obstacles included in our figure represent social psychological factors shown to influence other bystander intervention models; we organize the obstacles that we predict to be relevant at each step in the conceptual model. Thus, achieving the result of a helping action (implementing a classroom diversity-enhancing intervention) requires affirmation of multiple model inputs and overcoming many psychological obstacles. We assume that any given obstacle can stop the decision-making process at that step for a given faculty member, leading to inaction, but note that like the original model of helping, this process model can be, but is not necessarily, a linear process ( Darley and Latane, 1968 ).

Diversity intervention—resistance to action model decision inputs and potential obstacles.

Input 1: Notice That Underrepresentation within Biology Is a Problem.

One stumbling block (and one opportunity source) in the process of diversity interventions is that faculty may not notice that diversity in the field is lacking or assume it is simply a “normal” problem and/or that others are already addressing the problem. Faculty may expect everyone (including minorities) to “assimilate” to the classroom structures in place long held up by “tradition.” Some faculty, for example, might assume they should ignore a student’s race and gender and take a “color-blind” approach to teaching. Yet decades of research documents that a color-blind approach reproduces and even exacerbates inequality ( Richeson and Nussbaum, 2004 ; Plaut et al. , 2009 ). Assimilation expectations contribute to more bias and less engagement by URM students; in contrast, embracing difference and centering nondominant voices is related to a positive diversity climate that results in greater psychological engagement by minorities ( Plaut et al. , 2009 , 2020 ). The decision to implement a diversity-enhancing intervention, then, likely depends on whether faculty recognize the homogeneity of the field and whether they see the value of a truly diverse and multicultural workforce. Alternatively, even if faculty recognize underrepresentation in the field of biology, they may not recognize it as a problem in their local (i.e., institutional or departmental) context. Faculty may assume, for example, that other programs or universities are addressing the field’s problem, thereby removing diversity as a relevant problem at their local level.

Input 2: Interpret Underrepresentation in Biology as Needing Immediate Action.

Research on bystander inventions suggest that people look to others for cues to determine whether a problem requires immediate action. For diversity interventions, it is essential to get faculty to carefully consider and process information about the urgency of the problem with an open mind, and this can often be achieved if the communicator is someone with whom they typically agree or identify ( Wood, 2000 ). If the faculty member learns about the intervention, for example, from a communicator who is suspected to have an agenda or a self-interest, the message has much less influence ( Moskowitz, 1996 ). Top-down mandates and inauthentic diversity initiatives can lead to “diversity fatigue” that undermine intervention adoption efforts ( Lam, 2018 ; Smith et al. , 2021 ). Unfortunately, even within the academy, data related to diversity and discrimination can be met with suspicion ( Handley et al. , 2015 ) and alone will not pave the route to intervention implementation (e.g., Henderson et al. , 2011). Importantly, seeing colleagues do nothing provides relevant social information—in this case, faculty are likely to draw the conclusion that the problem does not require immediate action if they see that others in their same position are not acting with urgency. This phenomenon, called “pluralistic ignorance,” was identified in Latané and Darley (1970) and illustrates that people who want to help often remain silent or do not take action because they (incorrectly) assume that most others disagree with the need to help (e.g., Kitts, 2003 ; O’Gorman, 1975 ). Such pluralistic ignorance, for example, influences men’s allyship behaviors toward women in STEM; men want to help, but wrongly assume no one else does, and misperceiving the group norm results in inaction ( De Souza and Schmader, 2021 ). As such, the role of perceived group norms and social connections likely influences faculty’s change efforts within the undergraduate biology classroom ( Andrews et al. , 2016 ).

Input 3: Assume Responsibility to Intervene.

Many faculty might assume the responsibility for promoting diversity lies in the hands of university administrators (e.g., chief diversity officers) and that instructors need not bear direct responsibility. In this case, such a bystander effect implies a “diffusion of responsibility” for who should intervene ( Garcia et al. , 2002 ). The diffusion of responsibility increases as the number of alternative people who could help increases. In this case, the assumption is that someone else will help or that someone has already helped. Unclear expectations and lack of accountability contribute to diffusion of responsibility (e.g., Wegner and Schaefer, 1978). It is thus imperative to take advantage of social cues and social networks that emphasize prosocial goals, the value of diversity, and the need for each person to contribute to structural change to produce positive outcomes ( Abbate et al. , 2013 ; Campbell and O’Meara, 2013 ; Kiyama et al. , 2012 ). Of course, faculty must also know how to intervene.

Input 4: Know How to Intervene.

Faculty must first know the research on what works. Then, after faculty learn of an intervention that effectively closes equity gaps, they must also feel confident in knowing how to implement it correctly and feel supported to carry out the intervention. Much goes into the design and implementation of an intervention, and protocols must be written in a way that faculty feel able to carry out the intervention and simultaneously feel they have autonomy in adapting the intervention successfully. Even minor changes in intervention protocol could yield null results or, worse, create harm by unintentionally triggering other psychological processes ( Wilson, 2006 ). When faculty do feel confident about how to intervene, similar to the bystander model of helping, faculty must next consider the “cost” of helping ( Darley and Baston, 1973 ); from the time and effort associated with helping to the resources and rewards of taking action. The question becomes what type of information and how much support do faculty need to feel competent and able to adapt the intervention?

Obstacles to Helping.

As illustrated on the right side of Figure 1 , a wide range of obstacles can derail the path to action. The obstacles in our model are conceptually similar to the social psychological obstacles to helping identified by Latané and Darley (1970) and Thomas and Plaut (2008) , including pluralistic ignorance, diffusion of responsibility, and perceived costs of helping. Considering how these obstacles manifest in the context of faculty work and faculty pedagogical decision making may help us to understand why (and when) we observe a gap between motivated intentions and actual behavior ( Bathgate et al. , 2019 ; De Souza and Schmader, 2021 ).

Overview of the Present Study

As the first study focused on this model, our aims were to: 1) examine the potential for our model to explain instructors’ decisions related to diversity interventions and 2) conduct an initial exploration of how faculty think about diversity in general and diversity-enhancing interventions in particular. We developed an exploratory survey measure with subscales mapping onto our four conceptual model inputs and examined whether biology faculty responses on this survey were associated with their perceptions of, value for, and likelihood of implementing a specific diversity-enhancing intervention that we described to them (the UVI). We also conducted interviews with these faculty to explore how faculty think about diversity interventions more broadly. The interviews explored how mechanisms of resistance might manifest and function within our model, eliciting participants’ general perceptions of diversity-related issues, nuanced beliefs about and attitudes toward implementing diversity-enhancing interventions in general, and the UVI in particular.

We used an embedded mixed-methods approach, in which participants first completed a qualitative in-depth, semistructured interview and then completed a survey immediately after. The survey items align specifically to model inputs. From the interviews, we sought to understand the nuances of beliefs associated with our inputs for faculty participants, as well as both active and passive forms of resistance and support. Importantly, we did not design the interview protocol to directly test model input hypotheses, nor did we aim to quantify the qualitative data as further evidence of the salience of the four inputs in faculty participants’ thinking. Rather, the purpose of the interviews was to deepen our understanding of the ideas and beliefs faculty have related to diversity and diversity interventions. All research activities were carried out with institutional review board approval from San Diego State University (IRB no. HS2018-0018). Participants were given a $100 gift card for their time and effort in completing the interview and survey.

Researcher Positionality Statement

In advancing the call for transparency of perspective across qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methodologies with higher education ( Wells, and Stage, 2015 ) and STEM education research ( Hampton et al. , 2021 ), we recognize positionality and reflexivity as important components to our study. Thus, it was critical for each of us to examine our roles, possible bias, and influence on the research (reflexivity) and to account for how our social positioning influences our research design, use of theory, data collection, application of analytic and statistical techniques, and interpretation of results ( Lipscombe et al. , 2021 ). The authors have listed the social identifies and roles that they believe to be most relevant to their positionality on this paper. D.B.T. identifies as a White man and first-generation college student and has worked as a faculty member for more than 12 years at two minority-serving institutions (MSIs). His research focuses on how motivation is influenced by social processes, including one’s social identities and social interactions. He also works to improve educational programs, particularly those designed to promote equity, diversity, and inclusion in science and math education. M.-J.Y. is a queer BIWOC (Black/Indigenous/Woman of Color) postdoctoral scholar fellow with academic training in mixed-methods approaches in STEM education, biology, and Black studies. She draws on her multiple underrepresented identities in the STEM fields and higher education as she navigates American institutions of higher learning in varied roles as a first-generation college student, instructor, staff, and researcher. For over a decade, F.A.H. has focused her STEM education research on underrepresented and minoritized students and policy issues related to equity. This work draws on nearly two decades of experience as a higher education professional at several MSIs, including 15+ years of experience teaching at the college-level across four research universities, including serving as a tenure-track faculty member for the past nine years. Her scholarship is also enhanced by her personal experience as a Latina, low-income, first-generation college student, and community college graduate, who attended several MSIs. J.L.S. identifies as a woman, a lesbian, and was a first-generation college student. Her primary research interest is on how societal norms and stereotypes undermine or support people’s motivational experience. Her position as an academic leader and scholar-activist guide her approach to reshaping structures to positively impact research motivation and ensuring the highest level of integrity, inclusion, and ethics.

Participants and Recruitment

We recruited 40 faculty participants from eight 4-year U.S. universities, intentionally spread across the country, with five professors at each campus. We recruited participants via nonprobability snowball sampling ( Babbie, 2016 ). Team members emailed their biology department connections at various institutions to introduce the study and asked these connections to help forward study information to their colleagues. Potential participations were invited to take part in a study “that looks at pedagogical decision making in biology classrooms” and were given a flier that described the 60- to 90-minute interview as “aimed at gaining a better understanding of factors that inform teaching practices in introductory biology courses.” Referrals from faculty colleagues enhanced desirability to elicit interest to participate based on group membership status.

Potential faculty participants were first asked to complete an online prescreening questionnaire, which provided key information on participant attributes (demographics, types of classes and students they teach) and confirmed eligibility (i.e., currently teach or recently taught introductory-level or lower-division biology courses in a 4-year university). All participants ( N = 40) but one (a full-time postdoc with research and teaching responsibilities) held full-time faculty positions, with 57.5% tenure-track research faculty and 40% teaching-track faculty with mechanisms for promotion. Participants ranged in age from 31 to 75 years old (M = 51.92 years old). Of this sample, 45% were women, and 77.5% White, with the remaining participants identifying as Asian, Latinx, or multiracial. Additionally, 37.5% of the sample reported being a first-generation college-going student, 15% being recent immigrants or naturalized American citizens, and 7.5% identifying as LGBTQIA. With respect to their institutional contexts, seven of the eight institutions where these faculty work are considered as large public universities with ∼20,000 to 40,000 undergraduate populations; five of these campuses are tier 1 research (R1) universities and two are MSIs. Only one of the eight sites is a private R1 university with ∼5000 undergraduates.

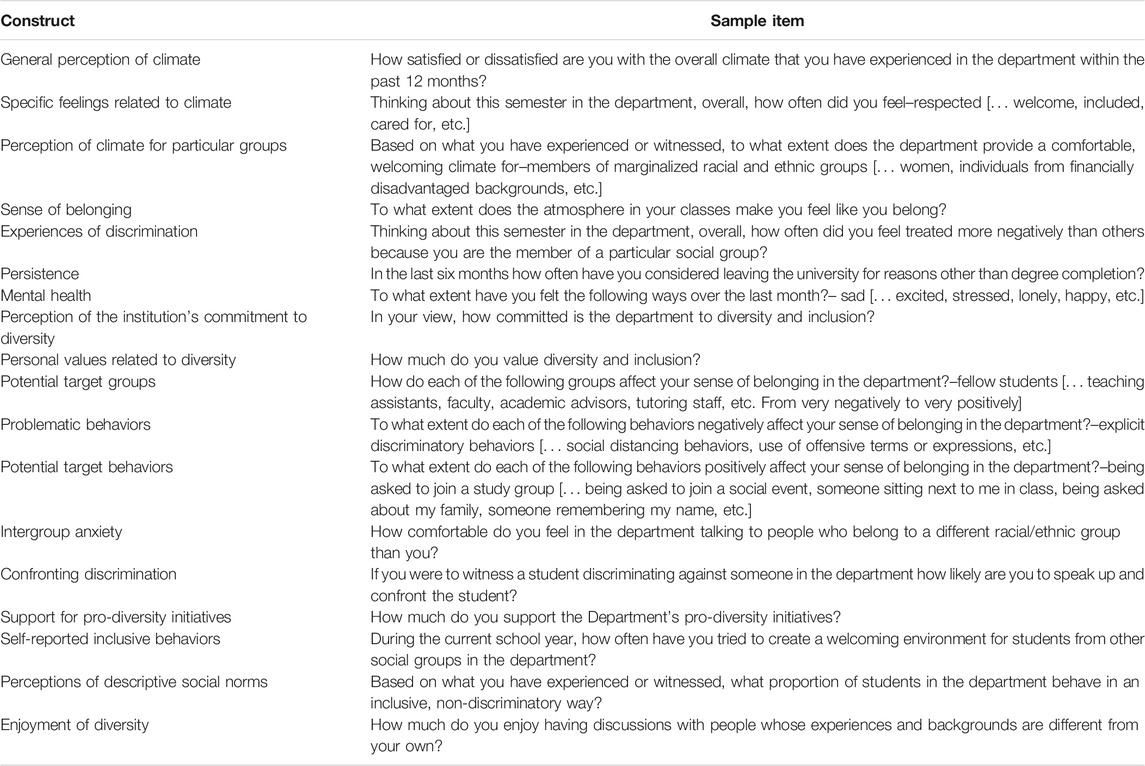

Survey Measures

All survey items are presented in Table 1 . To measure faculty participants’ endorsement of each of the four decision-making inputs proposed by the model, for the context of supporting diversity in biology, we adapted items from Nickerson et al. (2014) ’s measure of bystander intervention for bullying and sexual harassment. The measure consists of four subscales, mapping onto the four model inputs. To assess the value of the intervention, we measured the extent to which faculty value classroom diversity-enhancing interventions with five items drawn from research using the expectancy value theory of motivation (e.g., Eccles, 1983 ). All Likert-type items were statements to which faculty indicated a measure of agreement, from strongly disagree (1) to neither agree nor disagree (4) to strongly agree (7). Finally, we measured implementation likelihood with a single item that asked participants to estimate the likelihood they will implement a diversity-enhancing intervention in their classes this year, on a scale from 0 to 100. These measures were part of subset from a larger survey, and measures were presented in counterbalanced order.

Survey items and internal consistency statistics

a Implementation-likelihood item measured from 0 to 100. All other items measured from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree.

b α is Cronbach’s α measure of internal consistency.

Interview Design and Analysis

The interview portion of the study complements the quantitative survey through an embedded mixed-methods design, which intends for the two methods to answer corresponding research objectives to synthesize complementary quantitative and qualitative results to develop a more complete understanding of the phenomenon ( Creswell and Clark, 2011 ; Almalki, 2016 ). This allowed us to answer a secondary research aim with the qualitative data, which is tied to but different from the primary purpose of the quantitative analyses; in this case, to help explain how the mechanisms of resistance might manifest and function within model and to potentially identify strategies and solutions for overcoming obstacles. For example, the survey sought to quantify the extent to which faculty perceived underrepresentation is a problem that needs immediate action, while our interview questions elicited how participants conceptualize underrepresentation overall as an urgent problem to address (inputs 1 and 2). Furthermore, we were able to more deeply explore how these conceptual understandings are related to resistance and the potential impact on perceived value and adoption of diversity-enhancing interventions. Thus, while the purpose of quantitative analysis was to “test” the model, the qualitative analysis sought not only to better understand the nuances of participants’ decision-making processes, but to specifically examine how resistance manifests in faculty’s perceptions and practice and to inform possible strategies for action. To do this, we focused on the “emic” or insider’s perspective of faculty’s process, understanding, and meaning to discover the conceptual dimensions of central terms such as “diversity” and “underrepresentation” as a way to explore how faculty think about diversity in general and classroom diversity interventions in particular.

M.-J.Y. performed the 60- to 90-minute, in-depth, semistructured interviews, which were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Within the semistructured format, open-ended questions were used to give participants self-agency to provide rich data or “thick description” of what they interpret as relevant and significant in their experience ( Geertz, 1973 ; Merriam and Tisdell, 2015 ). The interview structure consisted of a quick introduction to build rapport, a qualitative dive into the participant’s positionality and praxis, and concluded with an introduction of the diversity-enhancing UVI by providing materials, evidence, and examples to elicit reactions on the feasibility of implementing such an intervention.

During the interview, participants’ prescreened demographic information was verbally verified and prompted follow-up questions on how and whether faculty members’ backgrounds inform their approaches to teaching and mentoring students. The semistructured interviews reflected distinct segments of questioning that aligned with the model, which allows us to draw concrete descriptions of participant experiences in relation to model inputs. For example, after referring to participants’ answers about their perceptions of gender, racial, and other representations (veteran status, transfer status, etc.) of diversity in their introductory biology classrooms, the interviewer asked the question, “Do you think underrepresentation is still an issue in your class/campus/field?” that relates to input 1: notice underrepresentation is a problem. See Table 2 for example interview questions. Although the model inputs are numbered chronologically, the questions sometimes did not follow this chronological order due to the fluid nature of the semistructured interview on a participant-by-participant basis. As each participant had a unique background, perspective, personality, and conversation style, individuals could share information that was relevant to another input before the interviewer asked that input’s question. In different parts of the interview, participants would sometimes share contradictory statements about their beliefs and experiences. In this way, the same participant could provide very different insight into the same model input.

Model inputs and sample interview questions

Qualitative Coding

Professionally transcribed interview transcripts were merged with audio files of respective participants in NVivo, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software. In vivo coding was performed by two trained coders, who highlighted specific portions of the transcripts and assigned them to nodes of code or “a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute” ( Saldana, 2016 ). Before the interviews, a preliminary parent code list was created based on the four model inputs and included codes to examine perceived obstacles. After all interviews were completed, M.-J.Y. then extended these five parent codes by generation of subcodes (and sometimes even sub-subcodes), based on an overview of emergent themes within each parent code. Developing codes that emerge from the experience of the participants is ideal instead of forcing participants’ own words to fit into theories that were derived from sources outside the actual interview ( Rowan, 1981 ). After expansion of the code list through peer debriefing, line-by-line coding identified more sub-subcodes that emerged from existing subcodes. To support the internal validity of the qualitative findings, interrater reliability calculated as percent agreement ranged between 85% and 98% across the pair of coders through an iterative process. At the completion of coding all transcripts, patterns were analyzed and themes emerged, with specific attention to the theoretical perspectives informing the study. Along with maximum variation sampling (of five professors per campus), rich, thick description from the in-depth interviews enhanced the external validity of the qualitative findings.

While the semistructured interview is dynamic in nature and allowed for follow-up questions to explore the model inputs, it was not rigidly structured to probe each of the model inputs in order. We present findings organized by model input to highlight the nuances of participants’ decision-making processes and specifically examine how resistance manifests in faculty’s perceptions and practices in ways that are conceptually connected to each input. We present faculty quotes with pseudonyms.

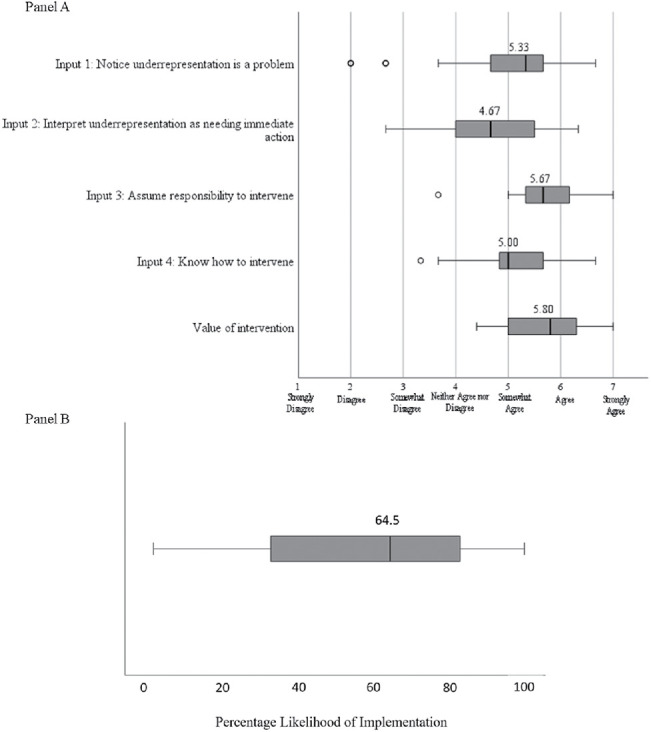

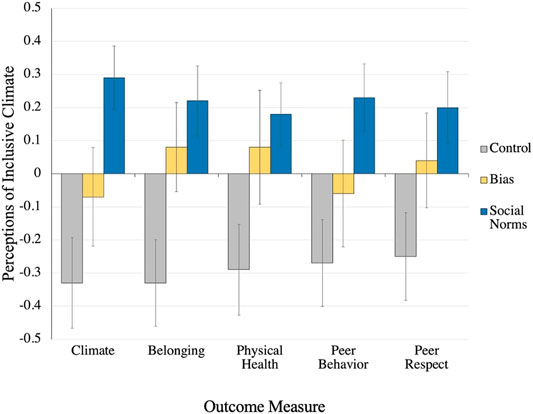

We organize the presentation of results by model input, but first provide an overview of descriptive survey data. Figure 2 illustrates the descriptive statistics for all survey measures, and Table 3 provides correlations among the survey variables. The small sample size limits the conclusions that can be drawn from significance tests of these correlations, but their overall magnitudes suggest moderate to strong relationships. The small sample size also limited our ability to adequately test for differences as a function of participant gender or ethnicity.

(A) Box-and-whisker plots showing the median and variation of the four model inputs and the value of intervention measures: (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree). The middle line in each box represents the median score for each measure of this faculty sample, while the far right side of the boxes represent the 75th percentile and the far left side of the boxes is the 25th percentile. The whiskers on the left and right represent the minimum and maximum scores, respectively, that are no greater than 1.5 times the interquartile range (scores within the box). Circles to the left of the whiskers are outliers beyond the range. (B) Box-and-whisker plot of the median and variation in the reported percentage likelihood of implementing the UVI (0–100% likelihood). The middle line in the box represents the median score for implementation likelihood, while the far right side of the box represent the 75th percentile and the far left side of the box is the 25th percentile. The whiskers on the left and right represent the minimum and maximum scores, respectively, that are no greater than 1.5 times the interquartile range (scores within the box).

Correlations among survey measures a

a N values range from 39–40 per measures. Scales from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree, except-implementation likelihood, which ranges from 0 to 100.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

First, we note that, although faculty overall reported high value for the UVI and reported being more likely than not to implement the diversity-enhancing intervention, we observed large variation for the implementation-likelihood measure, indicating little consensus among biology faculty in our sample with respect to their readiness for implementing the diversity-enhancing classroom intervention.

Input 1: Notice That Underrepresentation within Biology Is a Problem

Survey results suggest that, on average, faculty reported that they notice underrepresentation as a problem at a level above the scale midpoint. Our measure of input 1 was highly correlated with input 2 (interpret underrepresentation as needing immediate action) and moderately correlated with input 3 (assume responsibility to intervene). Responses to input 1 also positively correlated with perceived value of the intervention but not with implementation likelihood. Indeed, this input subscale was the only one that did not positively correlate with implementation intentions.

When our corresponding quantitative and qualitative results are compared, survey results indicate that faculty generally notice underrepresentation as a problem, yet participants relayed mixed messages related to how they conceptualize underrepresentation when asked to elaborate in the interviews. While participants overwhelmingly characterized their classrooms and campuses as supportive of increasing gender and racial/ethnic diversity, this did not always translate into acknowledgment that underrepresentation is a problem, nor was there consistency and clarity in defining the problem. Two common themes were revealed among our participant interviews in 1) defining diversity and 2) relying on anecdotal observations as evidence.

Participant interviews revealed blurred understandings of underrepresentation and diversity, which included color-blind views, broad definitions of diversity, focusing on wide-ranging identities (i.e., gender, class, first-generation college students), as well as a disconnect from the roots of underrepresentation in historically racialized oppressive systems within the United States. Most faculty participants praised their increasingly diverse campus, ranging from taking pride in all the cultures represented to widening the lens of what factors count for diversity in their predominantly White institutions. Yet many participants harbored unclear views about diversity and underrepresentation. Some faculty expressed color-blind ideologies, which clearly served as a direct barrier to understanding underrepresentation as a problem, as when Professor Laluarie stated:

I don’t see race. I mean, at least I try not to […] People come in with their own biases […] once you remove that distinction of the binary [racial] distinction, the bias is gone. There is no bias. You can’t have a bias.

While others were not explicitly color-blind, many avoided discussion of racial/ethnic identities and focused on other social identities, such as gender, class, first-generation college students, or even broader definitions such as rural students. Spotlighting these other identities and even the gains in representation, such as through gender parity or pointing to the growing number of international students as markers for diversity, allowed participants to shift the conversation away from race. For example, when asked about underrepresentation, one professor at an urban metropolitan R1 expressed that “white guys are the minority now” based on her recent anecdotal accounts of seeing all of the international students in her classroom. Only through several follow-up questions did these same professors later acknowledge that African-American students are underrepresented in biology classrooms. Other participants were vague in their reference of international students, and one participant confused international students with students of color whose families emigrated to the United States at least a generation ago. Although seemingly well intentioned in vocalizing the value of diversity in enriching classroom interactions, Professor Vogel, who has taught for almost 20 years at a public R1 university in a suburb of one of the biggest metropolitan areas in the country, seemed unclear about what “immigrant” versus “international” means:

So they’re not necessarily just immigrants. They, maybe, have born, been raised and a few generations here in the United States, but they still are international, if that—and they identify as international. If that makes sense. We’ve got a large number of people that have come here or the parents have come here and then they are raised here. I think so, yeah. Is that what you call it? I guess that’s what you call it or third-generation immigrants. That their grandparents or their parents came but then they’re born and raised here.

A key ingredient for the successful adoption of diversity initiatives in higher education is having a clear, data-driven understanding of equity gaps ( Kezar et al. , 2015 ). However, faculty often seemed to be relying on anecdotal evidence. When asked if underrepresentation was still a problem, Professor Mordrake replied:

I think it probably is. I know we have fewer African-American students than we should probably have. If we were going to—if it was going to be a representative slice of students at [this university], I think it’s slightly under. Now, I don’t have hard numbers to back that up. It’s more of an impression. In terms of Latino students, I don’t have the impression that it’s underrepresented. And sort of like Asian, Pacific Island, etc. I think that’s kind of a group that I see a lot of. So I don’t know. I don’t have hard numbers. But I have had the impression that there are fewer African-American students studying biology than would be a representative slice of the population.

Input 2: Interpret Underrepresentation in Biology as Needing Immediate Action

Survey results suggest that, on average, faculty reported that they interpret underrepresentation in biology as needing immediate action at a level above the scale midpoint, though there was substantial variability in ratings, as shown in Figure 2 . Our measure of input 2 was highly correlated with input 1 (notice underrepresentation as needing immediate action) and moderately correlated with input 3 (assume responsibility to intervene). Responses to input 2 also positive correlated with both perceived value of the intervention and implementation likelihood.

From the interviews, even when participants expressed their commitment to diversity, few addressed such issues in a way that conveyed a strong sense of urgency for immediate action. Most faculty downplayed underrepresentation as a high-priority problem by normalizing underrepresentation and discussing underrepresentation or diversity in ways that were disconnected from equity and social justice. This response often took the form of averting attention to other universities that are also not diverse, or to other universities that enroll more students of color than their own campuses. For example, Professor Wilton compares the underrepresentation in his private R1 campus to both the locale and the country:

Maybe within certain groups, I would say. Considering [this] city…and our makeup, I would say the university doesn’t align with that at all … Yeah. But I’m certain with other American universities, I’m pretty sure we pretty much have the same kind of makeup as most of them.

Although Professor Wilton initially acknowledged his campus’s student population did not reflect the diversity of the local community, he then reframed this concern by suggesting that campuses all over the country look very similar in composition. This minimizes the attention to diversity concerns within his own local context, that is, the institution or department.

A similar approach was seen when professors acknowledged that one’s own campus is not designated as an MSI, with the implication that the MSI campuses are the ones charged with serving underrepresented populations. Diffusing responsibility to another campus and pointing out that one’s campus is no worse off than another obscures the need for immediate local action. Professor Solanas—a faculty member who is also an appointed diversity administrator at a public R1 institution—observed:

Our [campus] student body does not reflect [this state]. Now there are some that do, like [these two other campuses]. I can’t remember, there’s a term for this. Where you have—it’s usually Latino populations, which is very large in [this state]. And so there’s only a couple of campuses, I think, that reflect that diversity and [we are] not one of them.

Furthermore, Professors Wilton’s and Solanas’s quotes both reflect a broader sentiment that was prevalent among participants in which underrepresentation and diversity were not linked to equity and social justice aims. In other words, diversity definitions were quite broad (see input 1) and underrepresentation discussions were primarily focused on numbers or structural diversity rather than problematizing and dismantling underlying structural barriers perpetuated by racism, sexism, and other enduring systems of oppression. Within our model, social cues inform one’s interpretation of whether addressing underrepresentation is an immediate need. Faculty’s uncomplicated perceptions of underrepresentation may be fostered by what Professor March describes as the overarching instrumental messaging from the institution:

I would say the university’s priority seems to be on getting diverse students in the door and then it ends there, right? It doesn’t, necessarily, completely end there, but their priority seems to be frontloaded as opposed to backloaded, […] it’s counterproductive to bring in a student for representation.

This disconnected perspective can also be seen at the departmental level, where some professors resisted evidence-based pedagogical initiatives by reinforcing the idea that they are already thinking about or performing classroom innovations on their own. Indeed, faculty generally felt they were proactive in their classrooms, with the majority reporting they already perform actions that promote pedagogical innovation. Further discussion revealed that the kinds of interventions being implemented were not typically diversity enhancing, and the idea that they were already engaging in broadly innovative strategies led to the conclusion for many faculty that there was little reason or urgency for considering additional innovations, such as diversity-enhancing interventions. For example, after sharing lots of details about all the pedagogical activities that he has used in a public R1 institution, Professor Monahan then expressed his distaste for classroom innovations that come from administration and even from colleagues who specialize in biology education:

They have these discipline-based education research postdocs, so it’s called the DBER Fellow. And they’re trying to tell people how to do—“Oh, it would be better if you did this in your class.” And I think, “You’ve never even taught a big class before,” and I’ve done maybe 65 or 70 big classes and thought a lot about it. So it’s helpful to hear about stuff, but at least in my personal case, I’m already thinking about a lot of it and talking with people anyway.

Thus, a barrier to interpreting underrepresentation as needing immediate action appears to include a feeling that one is “doing something already” that is already helping students, and not necessarily buying into recommendations based on empirical evidence of the effectiveness or from experts in the biology education field.

Input 3: Assume Responsibility to Intervene

Faculty reported that they assume responsibility to intervene at a mean level higher than all other inputs. Although the internal consistency measure for this scale was low, our measure of input 3 was moderately correlated with all other input measures. Responses to input 3 were also strongly positively correlated with both perceived value of the intervention and implementation likelihood. One reason that internal consistency of the survey measure may be low is because different items reflect two key themes that emerged (often among different participants) in the interviews: 1) deflecting responsibility to others both within and outside of the institution and 2) describing personal responsibility as contingent on adequate circumstances and resources. While faculty who did assume responsibility described navigating the resistance of others and barriers in gaining shared buy-in, when asked “Whose responsibility it is to address underrepresentation?,” some faculty shifted the focus away from their classrooms, departments, and institutions to emphasize the responsibility of outside sectors and agencies. For example, Professor Chen said:

I mean, I think, there’s work that could be done at the department level to promote diversity, but the pool of candidates needs to be there. And so I think it needs to come from the governmental level. […] I feel like we need to diversify the field, but first, we need to train the people to go into the field. And that’s a big—there’s not a lot of funding for that.

In addition, faculty focused on the role of K–12 in contributing to the “pipeline problem,” which averted attention to areas that were outside their personal or their institutions’ control. Participants generally agreed that addressing underrepresentation is a campus-wide responsibility, citing leadership, faculty, staff, and students as responsible actors, though rarely focusing on their own behaviors and more often diffusing responsibility across undefined sources. For example, Professor Huang described a “community responsibility,” wherein there needed to be open dialogue across stakeholders. Others focused more narrowly on the responsibility of administration, like Professor Sobchak, who noted that responsibility “comes from pretty high up in the university to try hard to increase underrepresented groups in STEM especially. They mandate things.” Even participants who said they do support top-down diversity-enhancing initiatives also expressed concern about the burden of having to adapt to university policies and initiatives. For example, public R1 instructor, Professor Cunningham, described this burden of fulfilling mandatory accommodations for students with disabilities that he supports in theory, but struggles to meet in reality:

So whether that’s proctors or somebody just—it just takes up more of my time. And like I said, I’m happy to do it. However, it bites into everything else that I need to do and it takes time away from other students. It takes time away from other things that are going to help me actually progress in my career, whether it’s research or any kind of other pedagogical exploration trying to figure out new things what to do […] My colleague who cotaught with me […] he’s seen it increase more and more the amount of time that he’s had to make for accommodations and he has the same sentiment. He’s not opposed to it. He thinks they’re good ideas. It’s just really, really draining and he wishes the institution would provide more support for that [….] And then the instructional institutional side of things isn’t saying, “Oh wait, they’re doing all these accommodations. Maybe it’s overburdening our instructors who are already swamped. Let’s see how we can help them.” That’s not happening.

Professor Cunningham (as well as his colleague) felt as though he was helping students but was frustrated by the lack of support that the university gives to the instructors implementing these policies. Certainly, resources are a valid concern, but a narrow focus on the lack of resources may also represent a form of resistance. Throughout our interviews, a clear tension emerged between faculty wanting autonomy and independence from top-down initiatives and faculty’s focus on a lack of university-supported resources to justify inaction. All participants expressed aversion to top-down recommendations on improving student success in biology classrooms, especially from university administrators and those that affect what happens in their own classrooms.

Many professors we interviewed did assume responsibility to make pedagogical innovations. Such efforts, however, seem to need to be started by an innovation-minded figure who can navigate various kinds of resistance from both colleagues and administration. Public R1 instructor Professor Sousa recalls the challenges and rewards of initiating active-learning opportunities in her department and beyond:

When I first started with active learning and embracing inclusivity, inequity, and diversity in classrooms, and I started running workshops on it, and I started being more subversive, not even telling people that the reason why they should be more active in their classroom or the reason why they might want to use clickers in their classroom was because there was a lot of data that showed that they helped a lot of people from a lot of different backgrounds. And they performed better whether or not the instructor was aiming to do that or not, right? So there’s stealth ways to get people to be more inclusive. Any place that wanted a workshop, I ran it…. But at first pass … just showing people that have never seen it before what it could look like, you could just watch the ideas popping into their head. And I thought, “This, in the end, might actually work out.” So I think that that’s—I did not feel empowered to do anything 20 years ago.

Professor Sousa seems personally invested in promoting “inclusivity, inequity, and diversity in classrooms”—something that she felt she could not do decades ago as a woman in a STEM field. She even took it upon herself to advance active learning in a stealthy way—sometimes not disclosing that it can be a diversity-enhancing initiative in order to eliminate any resistance from any potentially suspecting faculty and university administrators who may pigeonhole her as a diversity champion.

Input 4: Know How to Help

When presented with information about and materials on a specific diversity-enhancing pedagogical intervention—we used the UVI ( Harackiewicz et al. , 2016 ), survey results suggest that, on average, faculty reported being confident that they know how to intervene at a level above the scale midpoint. Our measure of input 4 was positively correlated with input 3 (assume responsibility to intervene). It was also strongly correlated with perceived value of the intervention and implementation likelihood.

During the interviews, most faculty participants also enumerated the various obstacles and costs related to implementation. We probed for the reactions to the UVI in particular to try and understand the perceived obstacles—and solutions—that emerged. Concern about the time and effort it takes to implement the UVI was expressed by most faculty. For example, in his public R1 institution, Professor Cunningham anticipates strong “pushback” against this classroom innovation because of the amount of time it would take:

There hasn’t been any faculty [pushback], so much so is most of it’s I just don’t have time to do this or I don’t think this will have that much impact. And so they just don’t do it. So it’s not that they don’t agree with it so much as they don’t—either they feel it’s not worth their time, or they just don’t have the time. And it’s usually they don’t have the time. Very rarely have I heard this is a waste of time or you shouldn’t be doing this. I don’t think I’ve ever heard that, especially at [our campus].

Faculty often expressed feeling overwhelmed and overworked in their jobs, so it is not surprising that asking faculty instructors to add something to their courses created an obstacle to action. The time needed for grading was a clear concern for the UVI, in particular. Participants communicated their concern with the time needed to grade a writing assignment in a large introductory biology (even with the provided rubric for grading and short nature of the writing assignment itself). When identified, this concern typically produced one of two outcomes. Although many faculty dismissed the practicality of the UVI because of the grading costs, a few others proactively offered solutions to the grading problem. They described ideas such as using the provided rubrics for standardization, online blind peer-grading (of the personal connection part of the UVI assignment), and sampling student responses for quick overview of examples being used. Inspired by a previous department-wide effort to promote student writing called “biologist’s journal” at a public MSI, Professor Huang created a way to facilitate grading such assignments in large introductory biology classes:

We’ve done those biologist’s journal[s]. I mean, for 300 people, I mean, I spend about 20, 30 minutes a week. We sample. I just sample, and then the TA is kind of taking care of the—as long as they meet the words requirement, turn in on time, and then not talking about garbage on top, and they will get the credit…. And I do a sample. By reading about 10 or 20 out of 300 people, you get a very good representative feeling of what they’re talking about … we do points.

Professor Huang’s solution demonstrates that a professor can be hands-on yet also efficient with grading a large class. His self-initiative offers creative solutions to help alleviate the perceived and actual costs associated with implementing an intervention such as the UVI.

Tenure-track research faculty also specifically discussed the concerns related to time associated with implementing pedagogical innovations at the expense of their time on other important outside efforts, such as research. One participant from a large R1 university, Professor Sobchak, relayed the realities of the reward system for tenure-track research professors:

For my research faculty, what they’re being judged on is their research and their research grants. They are not being—75%, that’s where the weight is. So you’ve got to take that into consideration when you’re asking them about effort in teaching.

This statement illustrates the difficulty of pedagogy innovation when teaching is viewed as secondary or even misaligned with a research academic’s professional identity ( Brownell and Tanner, 2012 ).

Participants also indicated a specific concern associated with overloading students with more work, as there already exist many class requirements and activities. Professors considered student buy-in as an important factor when making decisions about what to use or add to the existing curriculum. For example, public R1 instructor Professor Pfister dissected his pedagogical decision-making process about realistically incorporating UVI in his classes:

And so it’s not just finding the points for this, it’s if I add another thing in there, do I now have too many things and the students start getting scattered and losing track? And so what would I take out if I was going to put this in? So that’s the first thing I’d have to think about. Okay? Because I’m not sure that adding another thing is going to be—based on past experience, adding another thing can be problematic.

Certainly, it can overburden students to have more work added to what they already have to do in class; but if the instructor prioritizes the rationale for a specific assignment, then this new requirement can easily replace another existing activity.

We presented the diversity intervention—resistance to action model and examined the potential for our model to explain instructors’ decisions related to implementing diversity interventions. Overall, findings suggest that our theoretical model, which frames intervention as a “helping” action, is useful for understanding why social psychological factors promote or create obstacles to faculty decisions to implement (or not) a diversity-enhancing classroom intervention. Comparing study findings with our predicted model inputs and obstacles derived from social psychological theory and research reveals that, although the model was generally supported, the data did not directly address all predictions, support for some predictions remains ambiguous, and new predictions or extensions to the model are warranted.

Both survey and interview findings generally support the concepts in this model. Survey findings linked faculty beliefs corresponding to the model inputs to (in)action via perceptions of value and implementation intentions toward diversity-enhancing classroom interventions. These outcomes matter, because behavioral intentions are the best predictors of actual behavior (which was not possible to measure in this study context; Ajzen, 1991 ; Kim and Hunter, 1993 ; Webb and Sheeran, 2006 ). The interview data illustrated that, in many ways, the predictors of support and forms of resistance among faculty are similar to those seem within other organizational contexts ( Plaut et al. , 2020 ). Just as the survey findings demonstrated high correlations among the model inputs, interview findings suggested that information associated with each of the model inputs was relevant to shaping faculty decision making, even if faculty lived experiences do not follow the specific order. Relative to the neatly organized model in Figure 1 , we learned that the specific alignment of obstacles to steps is murkier than predicted.

One clear takeaway from our study is that the social psychological obstacles to helping behaviors also emerged in this context of biology faculty decision making when considering implementing a diversity-enhancing intervention. Like Thomas and Plaut’s ( 2008 ) model, as well as Latané and Darley’s ( 1970 ) bystander intervention model, our findings underscore that faculty decision making is not carried out in isolation. Rather, biology faculty look to (real or imagined) others, typically their peers (and decidedly not their administrative leaders), for social information that guides: their interpretation of whether underrepresentation is a problem, whether it requires immediate attention, whether they are personally responsible for taking steps to ameliorate the problem in their local contexts, and whether the obstacles are too great to warrant helping.

Study findings were mixed, however, with respect to support for our predictions about specific placements of social psychological obstacles in the model. Themes associated with diffusion of responsibility were highlighted throughout the interviews. Although we expected diffusion of responsibility to emerge as a barrier between “interpret underrepresentation as needing immediate action” (input 2) and “assume responsibility” (input 3), these themes emerged as relevant at multiple points in the model. Compared with other models of helping, diffusion of responsibility seems to be a particularly problematic obstacle for faculty because it is normative to locate the problem and/or responsibility of solving the problem of underrepresentation to many sources, including those earlier in the education pathway (e.g., K–12 education), to other universities or institutions (e.g., MSIs), and to others at one’s own university (e.g., institutional or departmental policies or offices).

In contrast, themes associated with pluralistic ignorance did not emerge clearly in the interviews. In bystander intervention models, pluralistic ignorance is a key barrier to interpreting the need for immediate action. When people see others also not providing help, they interpret the inaction as a cue that the problem is not urgent. What is unclear from our findings is whether pluralistic ignorance is not important in the faculty decision-making process or whether our methods did not adequately capture this obstacle. Although only further research can properly answer this question, we believe the latter to be the most likely explanation. Pluralistic ignorance typically derives from the lack of action; that is, social cues inferred from what people are not doing. In hindsight, we did not design our interviews to optimally focus on what did not happen among one’s peers. For example, several faculty described that their peers engaged in innovative pedagogies. Participants did not explicitly say that they attributed these innovation efforts as a cue that further action (focused on diversity) was not necessary. From the theoretical lens of our model, we interpret the lack of discussion about diversity-enhancing strategies, specifically, as social information signaling the normative belief that the problem of underrepresentation does not require further immediate action in the local departmental context beyond the more general innovative pedagogical efforts already taking place. Of course, this inference extrapolates beyond the data. More targeted research is therefore needed to better test the model’s predictions associated with pluralistic ignorance and related social cues inferred from inaction at the local department level.

Updating the Model and Generating New Hypotheses

Findings also suggest that our adaptation of the bystander intervention model for this specific decision context should be updated and that our initial exploration of how faculty think about diversity in general and diversity-enhancing interventions in particular helped identify new obstacles to incorporate into our framework. Table 4 displays the emergent themes related to resistance or obstacles to intervening that we identified.

Summary of resistance themes that emerged in interviews

Each of the emergent themes identified in our interviews provides greater specificity with respect to faculty decision making than would be expected from adapting bystander intervention models from other contexts. For example, much of the prior research on resistance to diversity in organizations has focused on participants’ views about their organization ( Thomas and Plaut, 2008 ). In the case of biology faculty, we observed tension between beliefs about underrepresentation as a problem in the field of biology versus in one’s local institutional or departmental context. The nature of a faculty position is both highly autonomous and embedded in layers of institutional structures (e.g., departments, colleges, universities, and the field of biology). Unlike other organizational contexts in which top-down policies can more easily define problems and direct specific actions of employees, faculty have much more autonomy to choose which problems they address, and how vigorously they pursue those problems. Many of the emergent themes reflect the subtle ways in which faculty passively resist personally taking on the problem of underrepresentation within the space they most control, their classrooms. Faculty were often easily dissuaded from action via a wide range of obstacles that did not appear to us to be insurmountable. Instead of engaging in problem solving about how to redistribute effort or seek help to implement the UVI, for example, concerns about time and task effort resulted in a decision to stop considering it as a practical option. Further, instead of taking personal responsibility to overcome obstacles, participants tended to expect their peers to lead pedagogical innovations and relayed information about the pedagogical innovations happening in their departments, such as active-learning strategies and technology-mediated tools. That said, a few participants proactively took personal responsibility—even if it meant enacting equity-enhancing curricular changes in stealthy manners to prevent even further pushback from colleagues, which is a tried-and-true intervention technique (e.g., Latimer et al. , 2014 ).

Limitations

The study has several key limitations. First, we only measured value and implementation likelihood—not actual behavior; and our methods did not allow for causal conclusions. What is needed next is a concerted effort to experimentally test strategies for promoting greater implementation intentions and behavioral implementation of diversity-enhancing interventions (including but not limited to the UVI). Identification of factors that lead to resistance seem to imply strategies to promote action, but a careful empirically driven approach to determine strategies that actually lead to behavior is essential to generate empirical scientific knowledge to advance implementation of diversity-enhancing interventions at scale.