Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

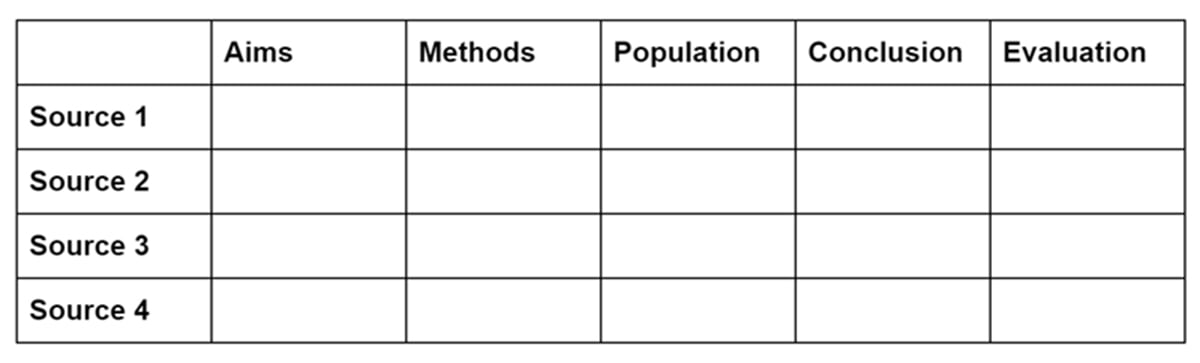

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

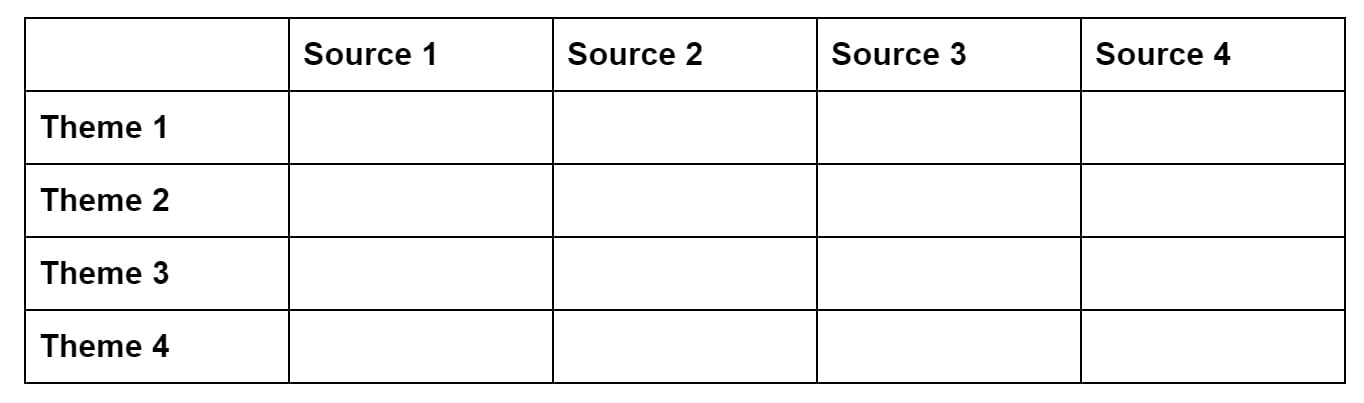

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

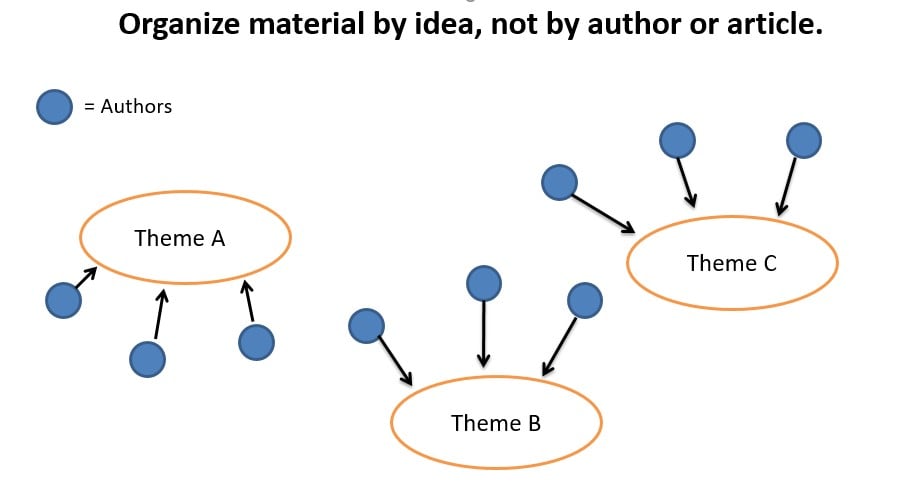

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Improve your Grades

Explanatory Synthesis Essay | Meaning, Types, Parts and Usage

October 18, 2021 by Prasanna

Explanatory Synthesis Essay: Essays are an essential part of education. They encourage students to write about topics that interest them, which help shape their intellectual growth. Essays also give students the opportunity to learn how to think critically and logically about issues, consider different perspectives, and articulate their thoughts through writing. One of the most common types of essays that students will come across is the synthesis essay.

You can also find more Essay Writing articles on events, persons, sports, technology and many more.

What is a Synthesis Essay?

A synthesis essay is a document that synthesises and condenses the information from different sources to create a coherent and well-structured argument or idea. The central idea behind a synthesis essay is to gather from two or more sources and then synthesise it to corroborate with a thesis.

Types of Synthesis Essay

There are 3 types of synthesis essay:

- Argumentative Synthesis Essay – An argumentative synthesis essay is a type of essay where you synthesize two or more perspectives and present your own arguments and justification as to why one side is correct.

- Explanatory Synthesis Essay – An explanatory synthesis essay requires the writer to analyze and synthesize information from various sources to create a single unified information that corroborates with a thesis. This type of essay is different from argumentative essays as the writer does not generally express his opinions unless they are factually accurate and verified.

- Literature Review Synthesis Essay – A literature review synthesis essay is an overview of the existing research in a particular area of study. You review studies in the field, identify gaps in knowledge, and propose new research goals.

In this article, we shall explore more about Explanatory Synthesis Essay in detail.

What is a Explanatory Synthesis Essay?

As mentioned previously, explanatory synthesis essay is an essay that is written in order to provide an explanation of something that has happened or is happening. The primary purpose of this essay is to create relevant information about a selected topic in a comprehensive and objective way. Essentially, the reader must gain a clearer or deeper perspective on the topic.

An important point of consideration is that an explanatory synthesis essay must not be biased. It must only state verified facts and the writer must also be careful with expressing their personal opinion.

Parts of an Explanatory Synthesis Essay

Like any other academic essay, an explanatory synthesis essay will consist of:

- An introduction

- A conclusion

Introduction : The introduction should be brief. This section must also explain how it relates to the rest of the paper. This paragraph can also be used to introduce any necessary terms related to the paper, relevant examples and any other details that provide a better context on the topic. In essence, the introductory paragraph must be unambiguous and not open to interpretation by the reader.

Body: The body of an explanatory synthesis essay must contain data that is collected from reliable sources about the same topic. For instance, if the essay’s topic is about the detrimental effects of plastic, then do not write sentences such as “I think / I believe plastic is harmful..” These sentences indicate bias or personal opinion – which is not typical for an explanatory synthesis essay.

Conclusion: Conclude the essay by summarising important facts and points. Also, ensure that there is no ambiguity in the concluding paragraph.

Points to Picking an Explanatory Synthesis Essay Topic

As discussed above, synthesis essays are not very open to interpretation and opinions, hence, the writer should carefully consider the following when selecting a topic for this type of essay:

- The topic must not be very general

- It has to be relevant

- Topic should not be vague

- Choose topics where factual data is easily accessible.

Important Essay Writing Tips and Guidelines

Regardless of the type of essay, the following tips and guidelines always ensures that the essay is academically relevant and also conforms to good writing practices:

- Do your research before you begin the essay – It is imperative that you do your research before you begin writing an essay. This will give you a better understanding of the topic at hand and ensure that you are able to produce quality work.

- Make sure your essay is well organized – Essay writing is a difficult process. To make it easier, you need to have a good organization for your essay. In the introduction, you should state your thesis and include a sentence about each of the three parts of an essay. In the body, you should have paragraphs with supporting evidence from the sources in the essay. In the conclusion, summarize the important points and other important details.

- Keep the essay concise: Concise essays are not only more readable but they also offer a more complete understanding of the topic. In general, the introduction provides a background to the essay as well as what is being studied or explored. It can also state what issue is being addressed and how it will be addressed.

- Use quotations and references : Quotations or excerpts offer outside perspective and additional information for the reader. Moreover, these can be used not just in essays, but also articles, blog posts and more.

- Do not use contractions or slang words: Contractions and slang words are often used in speech, but this is not a good idea in academic writing. Slang can sometimes be understood by a reader, but may seem unprofessional. Worst case scenario – the slang can cause confusion and lead to problems that may offend the reader.

FAQ’s on Explanatory Synthesis Essay

Question 1. What is an Explanatory Synthesis Essay?

Answer: An explanatory synthesis essay is a writing assignment that requires the student to synthesize information from several sources. The sources should cover a diverse range of viewpoints and stances on the issue being examined. This type of essay also does not cover the personal opinions of the writer.

Question 2. What are the parts of an Explanatory Synthesis Essay?

Answer: An explanatory synthesis essay includes three major parts: the Introduction (thesis statement,) Body (supporting evidence), and a conclusion.

Question 3. What are the types of synthesis essays?

Answer: There are 3 types of synthesis essays – Argumentative Synthesis Essay, Explanatory Synthesis Essay and Literature Review Synthesis Essay. The first two types are the most common and are regularly asked in schools and colleges.

Question 4. What are some important essay writing tips and guidelines?

Answer: When you are writing an essay, it is important to have a clear direction and structure. Be sure to have a defined topic sentence that clearly states the point of the essay. Also, in an explanatory synthesis essay, avoid using phrases that indicate personal opinion or bias. Do your research before you begin the essay. Make sure your essay is well organised, and do not use contractions or slang words. Lastly, do not forget to review the essay for grammar and spelling.

- Picture Dictionary

- English Speech

- English Slogans

- English Letter Writing

- English Essay Writing

- English Textbook Answers

- Types of Certificates

- ICSE Solutions

- Selina ICSE Solutions

- ML Aggarwal Solutions

- HSSLive Plus One

- HSSLive Plus Two

- Kerala SSLC

- Distance Education

Explanatory Synthesis Essays- Structure and How to write

Explaining things is critical to helping you navigate various life phases, including academics. But what can be challenging is taking complicated subjects, breaking them down, and thoroughly explaining them for others to understand.

And this is what explanatory synthesis essays do. Here, you take a complex theory or concept and explain it in terms of the existing knowledge that a learner already has. These essays not only help readers but the writer too.

Explanatory synthesis essays help you to develop critical and logical thinking skills and different perspective considerations. The net effect is to help you articulate your thoughts perfectly, even to the most layperson.

But if this is your first time hearing about this essay, this article will educate you further on how to write and other aspects so you can become a skilled explanatory synthesis essay writer.

What Is an Explanatory Synthesis Essay?

As explained, an explanatory synthesis essay explains a concept. It requires you to look at all available resources and provide a detailed, comprehensive, and objective answer to a problem or a theory.

Ideally, an explanatory synthesis essay aims to better understand a topic.

These essays are often based on research from other authors or researchers who have previously written on the topic. Further, they are usually found in academic journals that publish articles about discoveries, technological advances, and other issues related to science, medicine, and technology.

New Service Alert !!!

We are now taking exams and courses

They can also be found in scholarly books that discuss new theories of history or philosophy and in popular magazines and newspapers that address topics such as science fiction movies and television shows. However, they may vary from topic to topic, but it is always written in a way that allows the reader to understand the subject better.

What Is the Structure of an Explanatory Synthesis Essay?

The structure of an explanatory synthesis essay is basically the same as it is for any other essay. The difference is that instead of just presenting one point, you will have to give supporting pieces of evidence from reliable sources in any paragraph.

The structure has;

Introduction

The introduction is the gateway to your essay. As such, it should be welcoming, easy to grasp, and captivating so that readers can quickly understand what you will talk about. In addition, you should make it brief but also provide the most crucial information.

The aim here is to introduce the essay; the better you do it, the better the chances of scoring higher and having your article read.

Some of the information to include here is the thesis statement and why a reader should read the entire piece. You should also give some background information to help readers understand your thought process.

This is the main or bulk of your essay and is typically three paragraphs. The body entails evidence and facts about your topic and why and how it supports your thesis statement.

Typically, each paragraph has an opening section known as the topic sentence. This is the main idea of your paragraph and should be placed at the beginning of each new body paragraph. It should also be specific enough to guide your readers about the paragraph.

The second part is the supporting evidence, where each body paragraph contains supporting evidence for the topic sentence. These are usually facts or examples that illustrate what you mean. They can also include statistics or other helpful information that supports your main idea. You should try to have at least two pieces of supporting evidence per paragraph.

Finally, you end each paragraph by tying the topic sentence and your evidence to help readers see the relationship between the two.

The conclusion of an explanatory synthesis essay provides readers with the information they might need to understand your position on the topic. You can also use this section to remind them of what you have already said in the preceding paragraphs.

Essentially, you summarize everything you have said into a single paragraph and then show how that information supports your thesis statement.

How to Write an Explanation Synthesis Essay

Writing an explanatory synthesis essay is easy and fun if you know your way around it. And it is a great way to show your subject mastery and writing skills; thus, you should not shy away from them. Not only that, but they also provide you with a platform to share your ideas with other people.

To write a good synthesis essay, you must know how it works. You have to combine multiple sources into one text but maintain a level of objectivity and accuracy of information presented in each source. However, the result will be inaccurate and incomplete if you don’t follow these principles when writing your synthesis essay.

And if you’re looking for some inspiration about how to write an explanatory synthesis essay, here are some tips and tricks that will help you write an excellent paper.

1. Do Thorough Research

Explanatory synthesis essays require you to have multiple information sources. These essays are not about personal opinions, so you can’t write without referring to credible sources. Researching helps you find out the main points and points of view of different authors on one subject.

Additionally, researching helps you to understand the topic better, thus putting you in an excellent position to write about it without confusing your readers. And reading one source is not enough. In fact, you need to read at least three sources to write an effective essay. You can use one source as your primary one while the others as secondary sources or support for your argument.

Some of the sources that will help you are;

- Books – Books are usually written by experts in their fields and provide a detailed discussion of the topic. They are often published by university presses or academic publishers, who are more concerned with accuracy than commercial success.

- Journal articles. These are written by experts in their fields and published in peer-reviewed journals. These articles tend to be more technical than books, but they provide more up-to-date information on recent developments in an area of study.

- Newspaper articles – Newspaper articles can also help explain complex ideas to students who may not be familiar with them. However, it’s important to remember that newspapers often have a particular point of view on any given issue and should therefore be used with caution.

2. Organize your essay

Organizing your essay is an integral part of writing it. Organization helps you present a well-thought-out and coherent paper. If you don’t organize your thoughts, you will likely end up with a disorganized piece that will confuse the reader, even if you have good ideas.

You should also be mindful of the structure and what each part entails. Further, the evidence in the body paragraph should follow a specific order. The best way is to start with the most important or strong points and finish with the weakest.

Following this order builds confidence in your readers, and you come off as an authoritative writer. This is also the point you create your outline, which helps you see what your essay will look like.

Keep the Essay Concise

Conciseness does not mean being brief, but rather do not fluff your paper. It means carefully looking at every piece of information, keeping what adds value, and discarding the rest.

For example, your thesis statement should clearly state what you will prove in your paper. You should ensure you have a few key points that are clear and easy to understand, which will lead the reader down the path of understanding the rest of your paper.

Similarly, keep your paragraphs as concise as possible, as this will help you stay on topic and avoid rambling or repeating yourself. If your paragraphs are too long, they may be hard to follow, so try to shorten them as much as possible while ensuring they contain all of the vital information your reader needs.

A good way to do this is by using transitions between paragraphs. A transition is a word or phrase that shows the relationship between ideas in a sentence or paragraph. This helps you cut off unnecessary words while still showing the relationship between every paragraph with the thesis and between sentences.

Other tips to keep your essay as concise as possible include;

- Use simple language

- Use short sentences and paragraphs

- Don’t use fancy words or phrases that might confuse the reader

- Not using contractions or slang

Use Quotes and References

Your essay needs references as a way to support the information you write. And as a requirement, you should use different sources to help create the credibility of your argument.

Depending on your professor’s instructions, you should follow the prescribed reference style. You can also opt to use quotes from reputable individuals. These help spice up your piece and support every analysis you make.

Now you know what explanatory synthesis essays are and how to write one. They are crucial pieces of writing that help you demonstrate your research and research skills. Further, they allow you to learn more about an issue and explain it to anyone expertly.

And with the stated tips, you are now poised to become the next expert writer for explanatory synthesis essays in your class.

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2017

Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence

- Quan Nha Hong 1 ,

- Pierre Pluye 1 ,

- Mathieu Bujold 1 &

- Maggy Wassef 2

Systematic Reviews volume 6 , Article number: 61 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

45 Altmetric

Metrics details

Systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence can provide a rich understanding of complex phenomena. This type of review is increasingly popular, has been used to provide a landscape of existing knowledge, and addresses the types of questions not usually covered in reviews relying solely on either quantitative or qualitative evidence. Although several typologies of synthesis designs have been developed, none have been tested on a large sample of reviews. The aim of this review of reviews was to identify and develop a typology of synthesis designs and methods that have been used and to propose strategies for synthesizing qualitative and quantitative evidence.

A review of systematic reviews combining qualitative and quantitative evidence was performed. Six databases were searched from inception to December 2014. Reviews were included if they were systematic reviews combining qualitative and quantitative evidence. The included reviews were analyzed according to three concepts of synthesis processes: (a) synthesis methods, (b) sequence of data synthesis, and (c) integration of data and synthesis results.

A total of 459 reviews were included. The analysis of this literature highlighted a lack of transparency in reporting how evidence was synthesized and a lack of consistency in the terminology used. Two main types of synthesis designs were identified: convergent and sequential synthesis designs. Within the convergent synthesis design, three subtypes were found: (a) data-based convergent synthesis design, where qualitative and quantitative evidence is analyzed together using the same synthesis method, (b) results-based convergent synthesis design, where qualitative and quantitative evidence is analyzed separately using different synthesis methods and results of both syntheses are integrated during a final synthesis, and (c) parallel-results convergent synthesis design consisting of independent syntheses of qualitative and quantitative evidence and an interpretation of the results in the discussion.

Conclusions

Performing systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence is challenging because of the multiple synthesis options. The findings provide guidance on how to combine qualitative and quantitative evidence. Also, recommendations are made to improve the conducting and reporting of this type of review.

Peer Review reports

Systematic reviews have been used by policy-makers, researchers, and health service providers to inform decision-making [ 1 ]. Traditionally, systematic reviews have given preference to quantitative evidence (mainly from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and to clinical effectiveness questions). However, a focus on quantitative evidence is insufficient in areas where research is not dominated by RCTs [ 2 ]. For example, in several fields such as public health, RCTs are not always appropriate nor sufficient to address complex and multifaceted problems [ 3 ]. Also, while reviews focusing on RCTs can help to answer the question, “What works for whom?,” other important questions remain unanswered such as “Why does it work?,” “How does it work?,” or “What works for whom in what context?.” Such questions can be addressed by reviewing qualitative evidence. Indeed, the analysis of qualitative evidence can complement those of quantitative studies by providing better understanding of the impact of contextual factors, helping to focus on outcomes that are important for patients, families, caregivers, and the population and exploring the diversity of effects across studies [ 4 ].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in synthesizing evidence derived from studies of different designs. This new type of review has been labelled with various terms such as integrative review [ 5 ], mixed methods review [ 6 ], mixed methods research synthesis [ 7 ], mixed research synthesis [ 8 ], and mixed studies review [ 9 , 10 ]. These reviews can yield a rich and highly practical understanding of complex interventions and programs [ 9 , 10 ]. They can be used to provide (a) a deeper understanding of quantitative evidence, (b) a statistical generalization of findings from qualitative evidence, or (c) a corroboration of knowledge obtained from quantitative and qualitative evidence [ 9 ].

The past decade has been rich with methodological advancements of reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. For example, several critical appraisal tools for assessing the quality of quantitative and qualitative studies have been developed [ 9 , 11 , 12 ]. Also, new synthesis methods have been developed to integrate qualitative and quantitative evidence such as critical interpretive synthesis, meta-narrative synthesis, and realist synthesis [ 4 , 13 , 14 ]. In addition, researchers have been interested in defining and categorizing different types of synthesis designs (see Table 1 ). These types were inspired by the literature on mixed methods research, which is a research process integrating quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection and analysis [ 15 ]. The types of synthesis design developed are, as yet, theoretical; they have not been tested on a large sample of reviews. Therefore, it is necessary to gain a better understanding of how reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence are carried out. The aim of this review of reviews was to identify and develop a typology of synthesis designs and methods and to propose strategies for synthesizing qualitative and quantitative evidence.

This review of reviews will contribute to a better understanding of the extent of this literature and justify its relevance. The results will also provide a comprehensive roadmap on how reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence are carried out. It will provide guidance for conducting and reporting this type of review.

A review of systematic reviews combining qualitative and quantitative evidence (hereafter, systematic mixed studies reviews (SMSR)) was performed (Table 2 ). SMSR follows the typical stages of systematic review, with the particularity of including evidence from qualitative, quantitative, and/or mixed method studies [ 7 , 10 ]. It uses a mixed methods approach [ 7 , 10 ].

The focus of this review of reviews was on the synthesis process that is the sequence of events and activities regarding how the findings of the included studies were brought together. Thus, a “process-data conceptualization” was conducted [ 16 ] using a deductive-inductive approach, i.e., using concepts from the literature on mixed methods research as a starting point, but allowing for new concepts to emerge. Based on the literature on mixed methods research, three main questions were asked: (a) Was the evidence synthesized using qualitative and/or quantitative synthesis methods?, (b) Was there a sequence in the synthesis of the evidence?, and (c) Where did the integration of quantitative and qualitative evidence occur?

Information sources and search strategy

Reviews were searched in six databases (Medline, PsycInfo, Embase, CINAHL, AMED, and Web of Science) from their respective inception dates through December 8, 2014. A search strategy was developed by the first author with the help of two specialized librarians. It included only free text searching since the field of SMSR is still new and no controlled vocabulary exists (see Table 3 for full-search strategy in Medline). All the records were transferred to a reference manager software (EndNote X7) and duplicates were removed using the Bramer-method [ 17 ].

Eligibility criteria and selection

SMSRs were included in this review of reviews if they provided a clear description of search and selection strategies, a quality appraisal of included studies, and combined either (a) qualitative, quantitative, and/or mixed methods studies; (b) qualitative and mixed methods studies; (c) quantitative and mixed methods studies; or (d) only mixed methods studies. However, reviews that combined qualitative and mixed methods studies but only analyzed the qualitative evidence of the mixed methods studies were excluded. Likewise, reviews that included quantitative and mixed methods studies but only analyzed quantitative evidence were excluded. SMSRs limited to bibliometric analysis, as well as those that contained only a secondary analysis of studies from previous systematic reviews, were excluded. Also, reviews not published in English or French were excluded.

A three-step selection process was followed. First, all publications that were not journal papers were excluded in EndNote. Second, the remaining records were transferred to the DistillerSR software and two reviewers independently screened all the bibliographic records (titles and abstracts). When the two reviewers disagreed regarding the inclusion/exclusion of a bibliographic record, it was retained for further scrutiny at the next step. Third, two independent reviewers read the full texts of the potentially eligible reviews. Reviews for which the type of studies was not clear (e.g., no description of included studies) were excluded. Also, some reviews were excluded during the analysis because they considered quantitative surveys as qualitative studies. Disagreements were reconciled through discussion or arbitration by a third reviewer.

Data collection and synthesis

One reviewer extracted the following data using NVivo 10: year, country, number of included studies, review title, justification for combining qualitative and quantitative evidence, and synthesis methods mentioned.

The quality of the retained reviews was not critically appraised because the aim of this review of reviews was to have a better understanding of how the synthesis is performed in SMSRs. In general, performing an appraisal is useful to check the trustworthiness of individual studies to a review and if the quality might impact the review findings [ 18 ]. This review of reviews did not focus on the findings of each review but put emphasis on the synthesis method used and how the findings were presented. Also, while some tools for appraising systematic reviews of quantitative studies exist [ 19 , 20 ], to our knowledge, there is no tool for appraising the quality of SMSRs.

The data describing the synthesis processes of included reviews were analyzed using the visual mapping technique, which is commonly used for conceptualizing process data [ 16 ]. Two reviewers created visual diagrams to represent the synthesis process, i.e., the means by which the qualitative and quantitative evidence, synthesis methods, and findings were linked. These diagrams were then compared and categorized into ideal types. An ideal type is defined as the grouping of characteristics that are common to most cases of a given phenomenon [ 21 ].

The analysis focused on three concepts inspired by the literature on mixed methods research [ 22 – 24 ]: (a) synthesis methods, (b) sequence of data synthesis, and (c) integration of data and synthesis results.

Synthesis methods : Synthesis consists of the stage of a review when the evidence extracted from the individual sources is brought together [ 13 ]. The synthesis method was identified from information provided in the Methods and Results sections. In line with the literature on mixed methods research, the synthesis methods were classified as quantitative or qualitative based on the process and output generated. A synthesis method was considered quantitative when the main results on specific variables across included studies were summarized or combined [ 25 ]. Quantitative output is based on numerical values of variables, which are typically produced using validated and reliable checklists and scales and are used to produce numerical data and summaries (such as frequency, mean, confidence interval, and standard error) and conduct statistical analyses [ 26 ]. Conversely, a synthesis method was considered qualitative when it summarized or interpreted data to generate outputs such as themes, concepts, frameworks, or theories (inter-related concepts).

The distinction between qualitative and quantitative synthesis methods was clear in most cases. However, some synthesis methods required further discussion between the reviewers. For example, in this review of reviews, a distinction between qualitative and quantitative content analysis was made. Content analysis described in Neuendorf [ 27 ] and Krippendorff [ 28 ] was considered quantitative synthesis method because the coded categories are reliable variables and values allowing descriptive and analytical statistics. This method was developed over a century ago and is defined “as the systematic, objective, quantitative analysis of message characteristics” [ 27 ]. In contrast, qualitative content analysis produces themes and subthemes that are qualitative in nature [ 29 ]. Also, in some SMSRs, the synthesis methods were not considered quantitative even if numbers were provided in the results. For example, some presented a table of frequencies of the number of studies for each theme identified from a thematic synthesis. The synthesis was considered qualitative since the main outputs were themes, while the numbers did not provide a combined estimate of a specific variable. Moreover, some synthesis methods are not exclusively qualitative or quantitative. For example, configurational comparative method has been considered simultaneously quantitative and qualitative by the developers [ 30 ]. In this review of reviews, this method was considered quantitative because it relies on logical inferences (Boolean algebra) and aims to reduce cases to a series of variables. Another synthesis method requiring discussion was vote counting that is considered quantitative in the literature [ 31 ]. In this review of reviews, vote counting was considered qualitative when the results were only used for descriptive purpose.

Tables 4 and 5 present a list of quantitative and qualitative synthesis methods found in the literature [ 13 , 32 – 34 ]. When there was a discrepancy between the method described and the method used, the information from the latter was considered during the analysis. For example, some reviews described meta-analysis in the Methods section yet indicated in the Results section that the data were too heterogeneous to be combined quantitatively and a narrative analysis was, thus, used. In this case, the synthesis was considered as qualitative.

Within each review, one or several synthesis methods could be used. The synthesis process could be either qualitative (i.e., used one or several qualitative synthesis methods to analyze the included studies), quantitative (i.e., used one or several quantitative synthesis methods to analyze the included studies), or mixed (i.e., used both qualitative and quantitative synthesis methods to analyze the included studies).

Sequence : In the literature on mixed methods research, a sequence refers to a temporal relationship between qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection and analysis [ 15 ]. In this review of reviews, the sequence of the analysis was determined based on the number of phases of synthesis and whether the results of one phase informed the synthesis of a subsequent phase. For example, a qualitative synthesis of qualitative studies is done first to identify the components of an intervention (phase 1). Then, the quantitative studies are analyzed to quantify the effect of each component (phase 2). In this case, we considered there was a sequence because the results of the qualitative synthesis informed the quantitative synthesis.

Integration : In the literature on mixed methods research, integration is defined as the process of bringing (mixing) qualitative and quantitative approaches together and can be achieved at the level of the design (e.g., sequential and convergent designs), the methods (data collection and analysis), and the interpretation and reporting [ 35 , 36 ]. In this review of reviews, we adapted these levels of integration: (1) data, i.e., all evidence analyzed using a same synthesis method, (2) results of syntheses, i.e., the results of the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence are compared or combined, (3) interpretation, i.e., the discussion of the results of the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence, and (4) design.

Description of included reviews

The bibliographic database search yielded 7003 records of which 459 SMSRs were included in this review of reviews (Fig. 1 ). As seen in Fig. 2 , there has been an exponential progression of the number of publications per year, especially since 2010. In over a decade, the number has passed from nearly 10 per year to more than 100. The topics of the SMSRs were mainly in health and varied widely, from health care to public health. Some were on information sciences, management, education, and research. The first authors of the SMSRs came from 28 different countries. The countries producing the most SMSRs are England ( n = 179), Australia ( n = 71), the USA ( n = 53), Canada ( n = 45), and the Netherlands ( n = 20).

Number of systematic mixed studies reviews published per year

Several labels were used to name this type of review, with the most common being “systematic review” ( n = 277), followed by “literature review” ( n = 39), “integrative review” ( n = 35), and “mixed methods reviews” ( n = 24). Among those using the term systematic review, a small number specified in the title that they combined different types of evidence: “mixed systematic review” ( n = 2), and “systematic review of quantitative and qualitative” data, evidence, literature, research, or studies ( n = 23).

The number of studies included in the SMSRs ranged from 2 to 295 (mean = 29; SD = 33). The majority of SMSRs included qualitative and quantitative studies ( n = 249) or qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies ( n = 200). Few included only quantitative and mixed methods studies ( n = 8) or only qualitative and mixed methods studies ( n = 2).

Only 24% ( n = 110) of included reviews provided a clear rationale for combining quantitative and qualitative evidence. Authors described various reasons for performing SMSRs that fall into the following eight categories: (a) nature of the literature on a topic—to adapt the review method because of the limited evidence on the topic or absence of RCTs, (b) complexity of the phenomenon—to address a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, (c) broad coverage—to provide broader perspective and cover a wide range of purposes, (d) comprehensiveness—to provide a complete picture and deduce the maximum information from the literature, (e) thorough understanding—to gain better and detailed understanding of a phenomenon, (f) complementarity—to address different review questions (e.g., why and how) and complement the strengths and limitations of quantitative and qualitative evidence, (g) corroboration—to strengthen and support the results through triangulation, and (h) practical implication—to provide more meaningful and relevant evidence for practice.

Only 39% ( n = 179) of included reviews provided a full description of the synthesis method(s) with methodological references. The remainder provided information without reference ( n = 149), simply mentioned (labelled) the synthesis method used ( n = 41), or did not provide information about the synthesis ( n = 90). A variety of synthesis methods were used in the included reviews. Among the SMSRs that provided information on the synthesis methods, the most common method mentioned was thematic synthesis ( n = 129), followed by narrative synthesis ( n = 64), narrative summary ( n = 30), categorization/grouping ( n = 20), content analysis ( n = 30), meta-synthesis ( n = 25), meta-analysis ( n = 27), narrative analysis ( n = 11), meta-ethnography ( n = 9), textual narrative ( n = 7), framework synthesis ( n = 7), and realist synthesis ( n = 6).

Synthesis of results

Based on the sequence and integration concepts, two main types of synthesis designs were identified (Fig. 3 ): convergent and sequential synthesis designs. Within the convergent synthesis design, three subtypes were found: data-based, results-based, and parallel-results convergent synthesis designs. These synthesis designs were cross tabulated with the three types of synthesis methods (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed). This led to a total of 12 possible synthesis strategies that are represented in Table 6 . Reviews were found for eight of these possibilities.

Typology of synthesis design in mixed studies reviews. QL qualitative, QT quantitative. a Data-based convergent synthesis design. b Results-based convergent synthesis design. c Parallel-results convergent synthesis design

Convergent synthesis design: In this design, the quantitative and qualitative evidence is collected and analyzed during the same phase of the research process in a parallel or a complementary manner. Three subtypes were identified based on where the integration occurred.

Data-based convergent synthesis design (Fig. 3a ): This design was the most common type of synthesis design (Table 6 ). In this design, all included studies are analyzed using the same synthesis method and results are presented together. Since only one synthesis method is used for all evidence, data transformation is involved (e.g., qualitative data transformed into numerical values or quantitative data are transformed into categories/themes). This design usually addressed one review question. Among the SMSRs in this design, three main objectives were found. The first category sought to describe the findings of the included studies, and the synthesis methods ranged from summarizing each study to grouping main findings. The review questions were generally broad (similar to a scoping review) such as what is known about a specific topic. The second category consisted of SMSRs that sought to identify and define main concepts or themes using a synthesis method such as qualitative content analysis or thematic synthesis. The review questions were generally more specific such as identifying the main barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a program or types of impact. The third category included SMSRs that aimed to establish relationships between the concepts and themes identified from the included studies or to provide a framework/theory.

Results-based convergent synthesis design (Fig. 3b ): Nearly 9% of SMSRs were classified in this synthesis design (Table 6 ). In this design, the qualitative and quantitative evidence is analyzed and presented separately but integrated using another synthesis method. The integration could consist of comparing or juxtaposing the findings of qualitative and quantitative evidence using tables and matrices or reanalyzing evidence in light of the results of both syntheses. For example, Harden and Thomas [ 6 ] suggest performing a quantitative synthesis (e.g., meta-analysis) of trials and a qualitative synthesis of studies of people’s views (e.g., thematic synthesis). Then, the results of both syntheses are combined in a third synthesis. This type of design usually addresses an overall review question with subquestions.

Parallel-results convergent design (Fig. 3c ): A little over 17% of reviews were classified in this design (Table 6 ). In this design, qualitative and quantitative evidence is analyzed and presented separately. The integration occurs during the interpretation of results in the Discussion section. Some of these SMSRs included two or more complementary review questions. For example, health technology assessments evaluate several dimensions such as clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and acceptability of an intervention. The evidence of each dimension is reviewed separately and brought together in the discussion and recommendations.

Sequential synthesis design (Fig. 3 ): This design was found in less than 5% of the reviews (Table 6 ). It involves a two-phase approach where the data collection and analysis of one type of evidence occur after and are informed by the collection and analysis of the other type. This design usually addressed one overall review question with subquestions and both syntheses complemented each other. For example, in a review aiming at identifying the obstacles to treatment adherence, the qualitative synthesis provided a list of barriers and the quantitative synthesis reported the prevalence of these barriers and knowledge gaps (barriers for which prevalence was not estimated) [ 37 ].

The number of published SMSRs has considerably increased in the past few years. In a previous review of reviews in 2006, Pluye et al. [ 9 ] identified only 17 SMSRs. This shows that there is an increasing interest for this type of review and warrants the need for more methodological development in this field.

In accordance with the literature on mixed methods research, two main types of synthesis designs were identified in this review of reviews: convergent and sequential synthesis designs. Three subtypes of convergent synthesis were found: data-based convergent, results-based, and parallel-results convergent synthesis designs. The data-based convergent design was more frequently used probably because it is easier to perform, especially for a descriptive purpose. The other synthesis designs might be more complex but could allow for greater analytical depth and breadth of the literature on a specific topic. Also, focusing the analysis on the concepts of convergent and sequential designs allowed us to clarify and refine their definitions. Considering that the focus of the analysis was the synthesis process in SMSRs, the literature on process studies especially in the fields of management provides insight into these concepts. First, in line with Langley et al. [ 38 ], the convergent design can be defined as a process of gradual, successive, and constant refinements of synthesis and interpretation of the qualitative and quantitative evidence. Researchers are working forward in a non-linear manner guided by a cognitive representation of new data-based synthesis or results-based synthesis or interpretation of results to be created. Second, in line with Van de Ven [ 39 ], a sequential synthesis design can be defined, according to a developmental perspective (phase 1 informing phase 2; phase 2 building on the results of phase 1), as a change of focus at the level of data or synthesis over time and as a cognitive transition into a new phase (e.g., from qualitative to quantitative or from quantitative to qualitative).

The synthesis designs found in this review of reviews reflect those suggested by Sandelowski et al. [ 8 ] (see Table 1 ) who used the terms segregated , which can be similar to results-based and parallel-results convergent synthesis designs, integrated , which is comparable to data-based convergent synthesis design, and contingent designs, which could be considered as a form of sequential design. In this review of reviews, we used the mixed methods concepts and terminology because they account for the integration that may be present at the level of data, results, interpretation, or design.

As in Heyvaert et al. [ 22 ], the concepts found in the literature on mixed methods research to define the synthesis designs were used; yet, the definition of the synthesis method and integration concepts was somewhat different. In Heyvaert et al. [ 22 ], they focused on the relative importance of methods, i.e., whether the qualitative or the quantitative method was dominant or of equal status. This was not done in this review of reviews because measuring or documenting the dominance of a method is difficult given the influences of multiple factors (power, resources, expertise, time, training, and worldviews of each research team member, among other factors). Also, in Heyvaert et al. [ 22 ], they considered that integration could be partial (i.e., part of the qualitative and quantitative studies are involved separately in some or all stages) or full (i.e., all the qualitative and quantitative studies are involved in all the stages). In this review of reviews, the focus was put on where the integration occurred. Therefore, this review of reviews resulted in respectively four and three types of synthesis designs and methods, which led to propose 12 synthesis strategies, as compared to 18 in Heyvaert et al. [ 22 ].

In Frantzen and Fetters [ 40 ], three main types of convergent designs are suggested (see Table 1 ). Similarly, this review of reviews also found qualitative, quantitative, or mixed convergent synthesis design types. However, no distinction was made during the analysis between SMSRs including only qualitative and quantitative studies (basic type) and those also including mixed methods studies (advanced type) because this review of reviews aimed at defining ideal types of synthesis designs. The paper written by Frantzen and Fetters [ 40 ] went into deeper analysis of convergent design to provide detailed information on the steps to follow to integrate qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies.

Some SMSRs using sequential synthesis design were found in our sample of reviews. Pluye and Hong [ 10 ] suggested using the sequential exploratory or explanatory designs. In the exploratory sequential design, a qualitative synthesis is performed first and results inform the subsequent quantitative synthesis. Conversely, in an explanatory sequential design, the quantitative synthesis is done first and informs the subsequent qualitative synthesis. In this review of reviews, the sequence was defined as the results of one phase informing the other (not limited to the order of the syntheses) and no review was classified as sequential explanatory. In addition, 12 SMSRs performing only qualitative syntheses were found and could not be classified as exploratory or explanatory. For the sake of parsimony, we did not make a distinction between exploratory and explanatory sequential synthesis designs.

Implications for conducting and reporting mixed studies reviews

In light of this review of reviews and the literature on mixed methods research, four complementary key recommendations can be made regarding the title, justification, synthesis methods, and the integration of qualitative and quantitative data.

First, researchers should explicitly state in the title that the review included qualitative and quantitative evidence. Various terms are used to designate this type of review. Some SMSRs used the term “mixed” such as mixed systematic review, mixed methods review, mixed research synthesis, or mixed studies review. The term mixed has been used in the mixed methods literature to designate primary research designs combining qualitative and quantitative approaches [ 23 ]. In the field of review, mixing qualitative and quantitative evidence can be seen at two levels: study level and synthesis level [ 22 ]. Pluye et al. [ 9 ] suggested “mixed studies review” referring to a review of studies of different designs. This name focuses on the study level and does not prescribe a specific synthesis method. Others have suggested labelling this type of review as mixed methods review [ 6 , 22 ] wherein mixing occurs at both the level of the study and the synthesis. Another popular term is integrative review proposed by Whittemore and Knafl [ 5 ]. Integrative review is described as a type of literature review to synthesize the results of research, methods, or theories using a narrative analysis [ 41 ]. Currently, all these terms are used interchangeably without a clear distinction [ 40 ].

Second, researchers should provide a clear justification for performing a SMSR and describe the synthesis design used. In this review of reviews, this information was found in only 24% of the SMSRs. This lack of justification for using qualitative and quantitative evidence is also found in the literature on mixed methods research [ 42 ]. The rationale will influence the review questions and the choice of the synthesis design. For example, if quantitative and qualitative evidence is used for corroboration purpose, the convergent synthesis design may be more relevant. On the other hand, when they are used in complementarity such as using the quantitative studies to generalize qualitative findings or using qualitative studies to interpret, explain, or provide more insight to some quantitative findings, the sequential synthesis design may be more appropriate.

Third, results of this review of reviews suggest a need to recommend that researchers describe their synthesis methods and cite methodological references. Only 39% of the SMSRs provided a full description of the synthesis methods with methodological references. Various synthesis methods have been developed over the past decade [ 13 , 32 , 33 , 43 ]. Meta-analysis is the best known synthesis method to aggregate findings in reviews, especially for clinical effectiveness questions. However, when this method is not possible, researchers tend to omit describing the synthesis. Researchers should avoid limiting the description to what was not done such as using the sentence “because of the heterogeneity of studies, no meta-analysis was performed and data were analyzed narratively.” The term “narrative” can be confusing since it is often used differently by different authors. In some SMSRs, narrative analysis corresponded to summarizing each included study. In others, it consisted in grouping the different findings of included studies into main categories and summarizing the evidence of each category. Still, others followed Popay et al.’s [ 44 ] four main elements for narrative synthesis (i.e., develop a theoretical model, preliminary synthesis, relationship, and assess robustness). Hence, in addition to naming the synthesis method, we recommend that reviews should provide a clear description of what was done to synthesize the data and add methodological references. This will improve transparency of the review process, which is an essential quality of systematic reviews.

Fourth, researchers should describe how the data were integrated and discuss the insight gained from this process. Integration is an inherent component of mixed methods research [ 15 ], and careful attention must be paid to how integration is done and reported to enhance the value of a review. The synthesis designs outline that can provide guidance on how to integrate data (Fig. 3 ). Also, the discussion should include more than a simple wrap-up of results. It should clearly reflect on the added value and insight gained of combining qualitative and quantitative evidence into a review.

Limitations

The search strategy used was not comprehensive; thus, not all SMSRs were identified in this review of reviews. Indeed, the search was limited to six databases mainly in health and no hand searching was performed. As this review of reviews deals with methods, citation tracking of included SMSRs would not have provided additional relevant references. Nonetheless, our sample of included SMSRs was large ( n = 459) and sufficient to achieve the aim of this review of reviews.

To ensure a manageable sample size, selection of included reviews was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles. We acknowledge that the sample of included reviews might not include some innovative developments in this field, given that some recent SMSRs may be reported in other types of publications (e.g., conference abstracts or gray literature).

Finally, the synthesis methods were not classified as aggregative and configurative [ 45 , 46 ]. As mentioned in Gough et al. [ 45 ], some configurative synthesis can include aggregative component and vice versa. To avoid this confusion, the terms qualitative and quantitative synthesis methods were preferred. Moreover, these terms were used to align with the mixed methods research terminology. Yet, as discussed in the Methods section, the interpretation of some synthesis methods used in this review of reviews can be debatable.

The field of SMSR is still young, though rapidly evolving. This review of reviews focused on how the qualitative and quantitative evidence is synthesized and integrated in SMSRs and suggested a typology of synthesis designs. The analysis of this literature also highlighted a lack of transparency in reporting how data were synthesized and a lack of consistency in the terminology used. Some avenues for future research can be suggested. First, there is a need to reach consensus on the terminology and definition of SMSRs. Moreover, given the wide range of approaches to synthesis, clear guidance and training are required regarding which synthesis methods to use and when and how they should be used. Also, future research should focus on the development, validation, and reliability testing of quality appraisal criteria and standards of high-quality SMSRs. Finally, an adapted PRISMA statement for reporting SMSRs should be developed to help advance the field.

Abbreviations

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Qualitative

Quantitative

Randomized controlled trial

Systematic mixed studies review

Bunn F, Trivedi D, Alderson P, Hamilton L, Martin A, Pinkney E, et al. The impact of Cochrane Reviews: a mixed-methods evaluation of outputs from Cochrane Review Groups supported by the National Institute for Health Research. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(28):1–100. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-125 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Goldsmith MR, Bankhead CR, Austoker J. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative research in evidence-based patient information. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(3):262–70. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.046110 .

Victora CG, Habicht J-P, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):400–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.400 .

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Integrative approaches to qualitative and quantitative evidence. London, UK: Health Development Agency; 2004. Report No.: 1842792555.

Google Scholar

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Harden A, Thomas J. Methodological issues in combining diverse study types in systematic reviews. Int J Soc Res Meth. 2005;8(3):257–71. doi: 10.1080/13645570500155078 .

Article Google Scholar

Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. Using mixed methods research synthesis for literature reviews: the mixed methods research synthesis approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2016.

Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Res Schools. 2006;13(1):29–40.

Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(4):529–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009 .

Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:29–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440 .

Crowe M, Sheppard L. A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: alternative tool structure is proposed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(1):79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008 .

Sirriyeh R, Lawton R, Gardner P, Armitage G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: the development and evaluation of a new tool. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(4):746–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x .

Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10 Suppl 1:6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576 .

Tricco AC, Antony J, Soobiah C, Kastner M, MacDonald H, Cogo E, et al. Knowledge synthesis methods for integrating qualitative and quantitative data: a scoping review reveals poor operationalization of the methodological steps. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.12.011 .

Plano Clark VL, Ivankova NV. Mixed methods research: a guide to the field. SAGE mixed methods research series. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2015.

Langley A. Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad Manage Rev. 1999;24(4):691–710. doi: 10.2307/259349 .

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014 .

Booth A, Papaioannou D, Sutton A. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: SAGE Publications; 2012.

Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, et al. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 .

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009 .

Weber M, Freund J, Kamnitzer P, Bertrand P. Économie et société: les catégories de la sociologie. Paris: Pocket; 1995.

Heyvaert M, Maes B, Onghena P. Mixed methods research synthesis: definition, framework, and potential. Qual Quant. 2013;47(2):659–76. doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9538-6 .

Creswell JW, Plano CV. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2011.

Collins KM, O’cathain A. Introduction: ten points about mixed methods research to be considered by the novice researcher. Int J Mult Res Approaches. 2009;3(1):2–7. doi: 10.5172/mra.455.3.1.2 .

Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: a structured review of the methodological literature. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1999;4(1):49–55. doi: 10.1177/135581969900400112 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Porta MS, Greenland S, Hernán M, dos Santos SI, Last JM. A dictionary of epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014.

Book Google Scholar

Neuendorf KA. The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2002.

Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2012.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 .

Rihoux B, Marx A. QCA, 25 years after “the comparative method”: mapping, challenges, and innovations—mini-symposium. Polit Res Q. 2013;66(1):167–235. doi: 10.1177/1065912912468269 .

Hedges LV, Olkin I. Vote-counting methods in research synthesis. Psychol Bull. 1980;88(2):359. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.359 .

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(59). doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 .

Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53. doi: 10.1258/1355819052801804 .

Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Lillie E, Perrier L, Horsley T et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(114). doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-114 .

Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt2):2134–56. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 .

Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):554–61. doi: 10.1370/afm.1865 .

Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438 .

Langley A, Mintzberg H, Pitcher P, Posada E, Saint-Macary J. Opening up decision making: the view from the black stool. Organ Sci. 1995;6(3):260–79. doi: 10.1287/orsc.6.3.260 .

Van de Ven AH. Suggestions for studying strategy process: a research note. Strat Manag J. 1992;13(5):169–88. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250131013 .

Frantzen KK, Fetters MD. Meta-integration for synthesizing data in a systematic mixed studies review: insights from research on autism spectrum disorder. Qual Quant. 2015:1-27. doi: 10.1007/s11135-015-0261-6 .

Whittemore R, Chao A, Jang M, Minges KE, Park C. Methods for knowledge synthesis: an overview. Heart Lung. 2014;43(5):453–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.014 .

O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(2):92–8. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074 .

Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Antony J, Cogo E, MacDonald H, Lillie E, et al. A scoping review identifies multiple emerging knowledge synthesis methods, but few studies operationalize the method. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.030 .

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University; 2006.

Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1(28). doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28 .

Anderson LM, Oliver SR, Michie S, Rehfuess E, Noyes J, Shemilt I. Investigating complexity in systematic reviews of interventions by using a spectrum of methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(11):1223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.06.014 .

Abbott A. The causal devolution. Sociol Methods Res. 1998;27(2):148–81. doi: 10.1177/0049124198027002002 .

Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. An introduction to systematic reviews. London: SAGE Publications; 2012.

Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2013.

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2005.

Schwandt TA. The Sage dictionary of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2015.

Glass GV. Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educ Res. 1976;5:3–8. doi: 10.3102/0013189X005010003 .

Louis TA, Zelterman D. Bayesian approaches to research synthesis. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York: Russell Sage; 1994. p. 411–22.