Skinner’s Box Experiment (Behaviorism Study)

We receive rewards and punishments for many behaviors. More importantly, once we experience that reward or punishment, we are likely to perform (or not perform) that behavior again in anticipation of the result.

Psychologists in the late 1800s and early 1900s believed that rewards and punishments were crucial to shaping and encouraging voluntary behavior. But they needed a way to test it. And they needed a name for how rewards and punishments shaped voluntary behaviors. Along came Burrhus Frederic Skinner , the creator of Skinner's Box, and the rest is history.

What Is Skinner's Box?

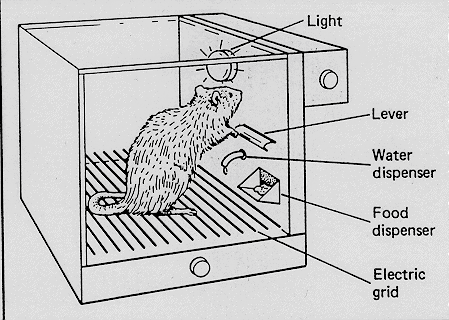

The "Skinner box" is a setup used in animal experiments. An animal is isolated in a box equipped with levers or other devices in this environment. The animal learns that pressing a lever or displaying specific behaviors can lead to rewards or punishments.

This setup was crucial for behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner developed his theories on operant conditioning. It also aided in understanding the concept of reinforcement schedules.

Here, "schedules" refer to the timing and frequency of rewards or punishments, which play a key role in shaping behavior. Skinner's research showed how different schedules impact how animals learn and respond to stimuli.

Who is B.F. Skinner?

Burrhus Frederic Skinner, also known as B.F. Skinner is considered the “father of Operant Conditioning.” His experiments, conducted in what is known as “Skinner’s box,” are some of the most well-known experiments in psychology. They helped shape the ideas of operant conditioning in behaviorism.

Law of Effect (Thorndike vs. Skinner)

At the time, classical conditioning was the top theory in behaviorism. However, Skinner knew that research showed that voluntary behaviors could be part of the conditioning process. In the late 1800s, a psychologist named Edward Thorndike wrote about “The Law of Effect.” He said, “Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to occur again in that situation.”

Thorndike tested out The Law of Effect with a box of his own. The box contained a maze and a lever. He placed a cat inside the box and a fish outside the box. He then recorded how the cats got out of the box and ate the fish.

Thorndike noticed that the cats would explore the maze and eventually found the lever. The level would let them out of the box, leading them to the fish faster. Once discovering this, the cats were more likely to use the lever when they wanted to get fish.

Skinner took this idea and ran with it. We call the box where animal experiments are performed "Skinner's box."

Why Do We Call This Box the "Skinner Box?"

Edward Thorndike used a box to train animals to perform behaviors for rewards. Later, psychologists like Martin Seligman used this apparatus to observe "learned helplessness." So why is this setup called a "Skinner Box?" Skinner not only used Skinner box experiments to show the existence of operant conditioning, but he also showed schedules in which operant conditioning was more or less effective, depending on your goals. And that is why he is called The Father of Operant Conditioning.

How Skinner's Box Worked

Inspired by Thorndike, Skinner created a box to test his theory of Operant Conditioning. (This box is also known as an “operant conditioning chamber.”)

The box was typically very simple. Skinner would place the rats in a Skinner box with neutral stimulants (that produced neither reinforcement nor punishment) and a lever that would dispense food. As the rats started to explore the box, they would stumble upon the level, activate it, and get food. Skinner observed that they were likely to engage in this behavior again, anticipating food. In some boxes, punishments would also be administered. Martin Seligman's learned helplessness experiments are a great example of using punishments to observe or shape an animal's behavior. Skinner usually worked with animals like rats or pigeons. And he took his research beyond what Thorndike did. He looked at how reinforcements and schedules of reinforcement would influence behavior.

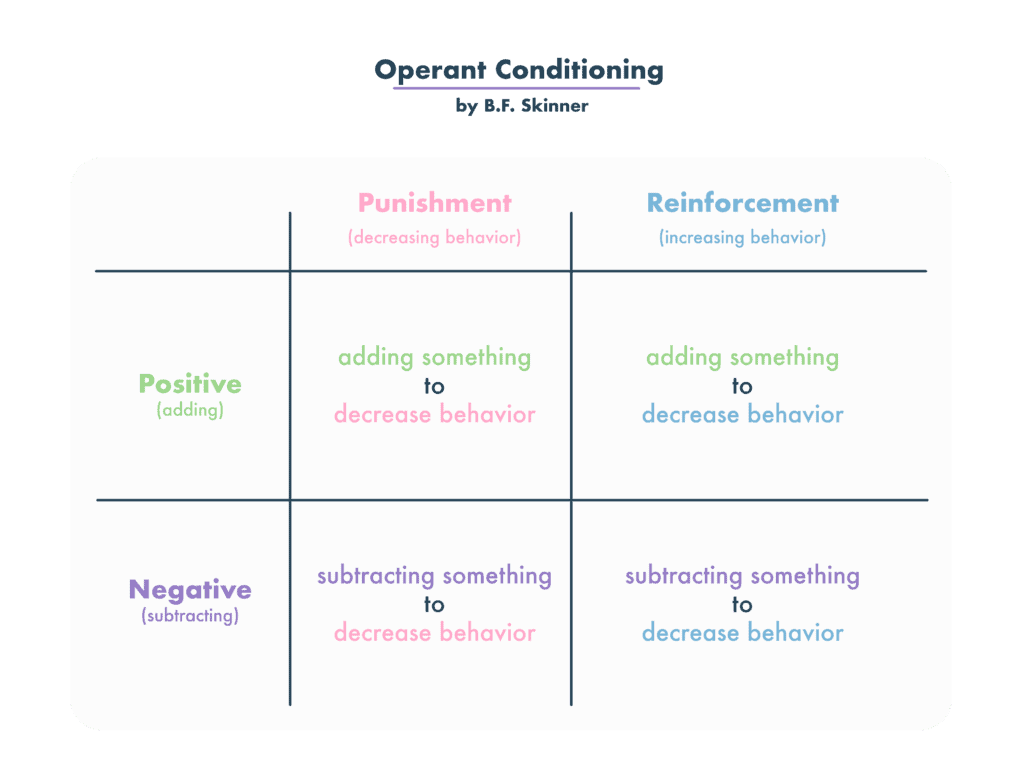

About Reinforcements

Reinforcements are the rewards that satisfy your needs. The fish that cats received outside of Thorndike’s box was positive reinforcement. In Skinner box experiments, pigeons or rats also received food. But positive reinforcements can be anything added after a behavior is performed: money, praise, candy, you name it. Operant conditioning certainly becomes more complicated when it comes to human reinforcements.

Positive vs. Negative Reinforcements

Skinner also looked at negative reinforcements. Whereas positive reinforcements are given to subjects, negative reinforcements are rewards in the form of things taken away from subjects. In some experiments in the Skinner box, he would send an electric current through the box that would shock the rats. If the rats pushed the lever, the shocks would stop. The removal of that terrible pain was a negative reinforcement. The rats still sought the reinforcement but were not gaining anything when the shocks ended. Skinner saw that the rats quickly learned to turn off the shocks by pushing the lever.

About Punishments

Skinner's Box also experimented with positive or negative punishments, in which harmful or unsatisfying things were taken away or given due to "bad behavior." For now, let's focus on the schedules of reinforcement.

Schedules of Reinforcement

We know that not every behavior has the same reinforcement every single time. Think about tipping as a rideshare driver or a barista at a coffee shop. You may have a string of customers who tip you generously after conversing with them. At this point, you’re likely to converse with your next customer. But what happens if they don’t tip you after you have a conversation with them? What happens if you stay silent for one ride and get a big tip?

Psychologists like Skinner wanted to know how quickly someone makes a behavior a habit after receiving reinforcement. Aka, how many trips will it take for you to converse with passengers every time? They also wanted to know how fast a subject would stop conversing with passengers if you stopped getting tips. If the rat pulls the lever and doesn't get food, will they stop pulling the lever altogether?

Skinner attempted to answer these questions by looking at different schedules of reinforcement. He would offer positive reinforcements on different schedules, like offering it every time the behavior was performed (continuous reinforcement) or at random (variable ratio reinforcement.) Based on his experiments, he would measure the following:

- Response rate (how quickly the behavior was performed)

- Extinction rate (how quickly the behavior would stop)

He found that there are multiple schedules of reinforcement, and they all yield different results. These schedules explain why your dog may not be responding to the treats you sometimes give him or why gambling can be so addictive. Not all of these schedules are possible, and that's okay, too.

Continuous Reinforcement

If you reinforce a behavior repeatedly, the response rate is medium, and the extinction rate is fast. The behavior will be performed only when reinforcement is needed. As soon as you stop reinforcing a behavior on this schedule, the behavior will not be performed.

Fixed-Ratio Reinforcement

Let’s say you reinforce the behavior every fourth or fifth time. The response rate is fast, and the extinction rate is medium. The behavior will be performed quickly to reach the reinforcement.

Fixed-Interval Reinforcement

In the above cases, the reinforcement was given immediately after the behavior was performed. But what if the reinforcement was given at a fixed interval, provided that the behavior was performed at some point? Skinner found that the response rate is medium, and the extinction rate is medium.

Variable-Ratio Reinforcement

Here's how gambling becomes so unpredictable and addictive. In gambling, you experience occasional wins, but you often face losses. This uncertainty keeps you hooked, not knowing when the next big win, or dopamine hit, will come. The behavior gets reinforced randomly. When gambling, your response is quick, but it takes a long time to stop wanting to gamble. This randomness is a key reason why gambling is highly addictive.

Variable-Interval Reinforcement

Last, the reinforcement is given out at random intervals, provided that the behavior is performed. Health inspectors or secret shoppers are commonly used examples of variable-interval reinforcement. The reinforcement could be administered five minutes after the behavior is performed or seven hours after the behavior is performed. Skinner found that the response rate for this schedule is fast, and the extinction rate is slow.

Skinner's Box and Pigeon Pilots in World War II

Yes, you read that right. Skinner's work with pigeons and other animals in Skinner's box had real-life effects. After some time training pigeons in his boxes, B.F. Skinner got an idea. Pigeons were easy to train. They can see very well as they fly through the sky. They're also quite calm creatures and don't panic in intense situations. Their skills could be applied to the war that was raging on around him.

B.F. Skinner decided to create a missile that pigeons would operate. That's right. The U.S. military was having trouble accurately targeting missiles, and B.F. Skinner believed pigeons could help. He believed he could train the pigeons to recognize a target and peck when they saw it. As the pigeons pecked, Skinner's specially designed cockpit would navigate appropriately. Pigeons could be pilots in World War II missions, fighting Nazi Germany.

When Skinner proposed this idea to the military, he was met with skepticism. Yet, he received $25,000 to start his work on "Project Pigeon." The device worked! Operant conditioning trained pigeons to navigate missiles appropriately and hit their targets. Unfortunately, there was one problem. The mission killed the pigeons once the missiles were dropped. It would require a lot of pigeons! The military eventually passed on the project, but cockpit prototypes are on display at the American History Museum. Pretty cool, huh?

Examples of Operant Conditioning in Everyday Life

Not every example of operant conditioning has to end in dropping missiles. Nor does it have to happen in a box in a laboratory! You might find that you have used operant conditioning on yourself, a pet, or a child whose behavior changes with rewards and punishments. These operant conditioning examples will look into what this process can do for behavior and personality.

Hot Stove: If you put your hand on a hot stove, you will get burned. More importantly, you are very unlikely to put your hand on that hot stove again. Even though no one has made that stove hot as a punishment, the process still works.

Tips: If you converse with a passenger while driving for Uber, you might get an extra tip at the end of your ride. That's certainly a great reward! You will likely keep conversing with passengers as you drive for Uber. The same type of behavior applies to any service worker who gets tips!

Training a Dog: If your dog sits when you say “sit,” you might treat him. More importantly, they are likely to sit when you say, “sit.” (This is a form of variable-ratio reinforcement. Likely, you only treat your dog 50-90% of the time they sit. If you gave a dog a treat every time they sat, they probably wouldn't have room for breakfast or dinner!)

Operant Conditioning Is Everywhere!

We see operant conditioning training us everywhere, intentionally or unintentionally! Game makers and app developers design their products based on the "rewards" our brains feel when seeing notifications or checking into the app. Schoolteachers use rewards to control their unruly classes. Dog training doesn't always look different from training your child to do chores. We know why this happens, thanks to experiments like the ones performed in Skinner's box.

Related posts:

- Operant Conditioning (Examples + Research)

- Edward Thorndike (Psychologist Biography)

- Schedules of Reinforcement (Examples)

- B.F. Skinner (Psychologist Biography)

- Fixed Ratio Reinforcement Schedule (Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Helping your fellow rat: Rodents show empathy-driven behavior

Rats free trapped companions, even when given choice of chocolate instead.

The first evidence of empathy-driven helping behavior in rodents has been observed in laboratory rats that repeatedly free companions from a restraint, according to a new study by University of Chicago neuroscientists.

The observation, published today in Science , places the origin of pro-social helping behavior earlier in the evolutionary tree than previously thought. Though empathetic behavior has been observed anecdotally in non-human primates and other wild species, the concept had not previously been observed in rodents in a laboratory setting.

“This is the first evidence of helping behavior triggered by empathy in rats,” said Jean Decety, the Irving B. Harris Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry. “There are a lot of ideas in the literature showing that empathy is not unique to humans, and it has been well demonstrated in apes, but in rodents it was not very clear. We put together in one series of experiments evidence of helping behavior based on empathy in rodents, and that’s really the first time it’s been seen.”

The study demonstrates the deep evolutionary roots of empathy-driven behavior, said Jeffrey Mogil, the E.P. Taylor professor in pain studies at McGill University, who has studied emotional contagion of pain in mice.

“On its face, this is more than empathy, this is pro-social behavior,” said Mogil, who was not involved in the study. “It’s more than has been shown before by a long shot, and that’s very impressive, especially since there’s no advanced technology here."

The experiments, designed by psychology graduate student and first author Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal with co-authors Decety and Peggy Mason, placed two rats that normally share a cage into a special test arena. One rat was held in a restrainer device — a closed tube with a door that can be nudged open from the outside. The second rat roamed free in the cage around the restrainer, able to see and hear the trapped cagemate but not required to take action.

The researchers observed that the free rat acted more agitated when its cagemate was restrained, compared to its activity when the rat was placed in a cage with an empty restrainer. This response offered evidence of an “emotional contagion,” a frequently observed phenomenon in humans and animals in which a subject shares in the fear, distress or even pain suffered by another subject.

While emotional contagion is the simplest form of empathy, the rats’ subsequent actions clearly comprised active helping behavior, a far more complex expression of empathy. After several daily restraint sessions, the free rat learned how to open the restrainer door and free its cagemate. Though slow to act at first, once the rat discovered the ability to free its companion, it would take action almost immediately upon placement in the test arena.

“We are not training these rats in any way,” Bartal said. “These rats are learning because they are motivated by something internal. We’re not showing them how to open the door, they don’t get any previous exposure on opening the door, and it’s hard to open the door. But they keep trying and trying, and it eventually works.”

To control for motivations other than empathy that would lead the rat to free its companion, the researchers conducted further experiments. When a stuffed toy rat was placed in the restrainer, the free rat did not open the door. When opening the restrainer door released his companion into a separate compartment, the free rat continued to nudge open the door, ruling out the reward of social interaction as motivation. The experiments left behavior motivated by empathy as the simplest explanation for the rats’ behavior.

“There was no other reason to take this action, except to terminate the distress of the trapped rats,” Bartal said. “In the rat model world, seeing the same behavior repeated over and over basically means that this action is rewarding to the rat.”

As a test of the power of this reward, another experiment was designed to give the free rats a choice: free their companion or feast on chocolate. Two restrainers were placed in the cage with the rat, one containing the cagemate, another containing a pile of chocolate chips. Though the free rat had the option of eating all the chocolate before freeing its companion, the rat was equally likely to open the restrainer containing the cagemate before opening the chocolate container.

“That was very compelling,” said Mason, Professor in Neurobiology. “It said to us that essentially helping their cagemate is on a par with chocolate. He can hog the entire chocolate stash if he wanted to, and he does not. We were shocked.”

Now that this model of empathic behavior has been established, the researchers are carrying out additional experiments. Because not every rat learned to open the door and free its companion, studies can compare these individuals to look for the biological source of these behavioral differences. Early results suggested that females were more likely to become door openers than males, perhaps reflecting the important role of empathy in motherhood and providing another avenue for study.

“This model of empathy and helping behavior opens the path for elucidating aspects of the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms that were not accessible until now.” Bartal said.

The experiments also provide further evidence that empathy-driven helping behavior is not unique to humans – and suggest that Homo sapiens could learn a lesson from its rat cousins.

“When we act without empathy we are acting against our biological inheritance," Mason said. "If humans would listen and act on their biological inheritance more often, we’d be better off."

The paper, “Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats,” will be published Dec. 9 by the journal Science . Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Science Foundation.

Top Stories

Uchicago fourth-year student named 2025 rhodes scholar, uchicago celebrates opening of john w. boyer center in paris.

- Argonne, UChicago partner to accelerate discovery of new cancer therapies using AI

Get more at UChicago news delivered to your inbox.

Media Citations

Rats show empathy and free their trapped companions

A new model of empathy: the rat

Related Topics

Latest news.

Global Impact

Big Brains podcast

Big Brains podcast: Can we predict the unpredictable? with J. Doyne Farmer

Meet A UChicagoan

Unraveling the ancient past, one tablet at a time

Go 'Inside the Lab' at UChicago

Explore labs through videos and Q&As with UChicago faculty, staff and students

Materials Science

In bioelectronics breakthrough, scientists create soft, flexible semiconductors

Telescopes and Cosmos

Latest findings from the South Pole Telescope bolster our model of the universe

Around uchicago.

Geophysical Sciences

UChicago scientist develops new paradigm to predict behavior of atmospheric rivers

Selwyn rogers elected to national academy of medicine.

UChicago Medicine

$75 million donation from AbbVie Foundation to support UChicago Medicine’s new …

New Program

UChicago offers new master’s program in environmental science

Materials science

UChicago scientists invent a way to bond diamond layers for quantum devices

UChicago scientists invent faster method to make advanced membranes for water filters

Film History

“Throughout my time at UChicago, I’ve sought to provide opportunities to share scholarship with the public”

Rhodes Scholar

UChicago fourth-year student named Rhodes Scholar

IMAGES

VIDEO