The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

What is the Significance of a Study? Examples and Guide

If you’re reading this post you’re probably wondering: what is the significance of a study?

No matter where you’re at with a piece of research, it is a good idea to think about the potential significance of your work. And sometimes you’ll have to explicitly write a statement of significance in your papers, it addition to it forming part of your thesis.

In this post I’ll cover what the significance of a study is, how to measure it, how to describe it with examples and add in some of my own experiences having now worked in research for over nine years.

If you’re reading this because you’re writing up your first paper, welcome! You may also like my how-to guide for all aspects of writing your first research paper .

Looking for guidance on writing the statement of significance for a paper or thesis? Click here to skip straight to that section.

What is the Significance of a Study?

For research papers, theses or dissertations it’s common to explicitly write a section describing the significance of the study. We’ll come onto what to include in that section in just a moment.

However the significance of a study can actually refer to several different things.

Working our way from the most technical to the broadest, depending on the context, the significance of a study may refer to:

- Within your study: Statistical significance. Can we trust the findings?

- Wider research field: Research significance. How does your study progress the field?

- Commercial / economic significance: Could there be business opportunities for your findings?

- Societal significance: What impact could your study have on the wider society.

- And probably other domain-specific significance!

We’ll shortly cover each of them in turn, including how they’re measured and some examples for each type of study significance.

But first, let’s touch on why you should consider the significance of your research at an early stage.

Why Care About the Significance of a Study?

No matter what is motivating you to carry out your research, it is sensible to think about the potential significance of your work. In the broadest sense this asks, how does the study contribute to the world?

After all, for many people research is only worth doing if it will result in some expected significance. For the vast majority of us our studies won’t be significant enough to reach the evening news, but most studies will help to enhance knowledge in a particular field and when research has at least some significance it makes for a far more fulfilling longterm pursuit.

Furthermore, a lot of us are carrying out research funded by the public. It therefore makes sense to keep an eye on what benefits the work could bring to the wider community.

Often in research you’ll come to a crossroads where you must decide which path of research to pursue. Thinking about the potential benefits of a strand of research can be useful for deciding how to spend your time, money and resources.

It’s worth noting though, that not all research activities have to work towards obvious significance. This is especially true while you’re a PhD student, where you’re figuring out what you enjoy and may simply be looking for an opportunity to learn a new skill.

However, if you’re trying to decide between two potential projects, it can be useful to weigh up the potential significance of each.

Let’s now dive into the different types of significance, starting with research significance.

Research Significance

What is the research significance of a study.

Unless someone specifies which type of significance they’re referring to, it is fair to assume that they want to know about the research significance of your study.

Research significance describes how your work has contributed to the field, how it could inform future studies and progress research.

Where should I write about my study’s significance in my thesis?

Typically you should write about your study’s significance in the Introduction and Conclusions sections of your thesis.

It’s important to mention it in the Introduction so that the relevance of your work and the potential impact and benefits it could have on the field are immediately apparent. Explaining why your work matters will help to engage readers (and examiners!) early on.

It’s also a good idea to detail the study’s significance in your Conclusions section. This adds weight to your findings and helps explain what your study contributes to the field.

On occasion you may also choose to include a brief description in your Abstract.

What is expected when submitting an article to a journal

It is common for journals to request a statement of significance, although this can sometimes be called other things such as:

- Impact statement

- Significance statement

- Advances in knowledge section

Here is one such example of what is expected:

Impact Statement: An Impact Statement is required for all submissions. Your impact statement will be evaluated by the Editor-in-Chief, Global Editors, and appropriate Associate Editor. For your manuscript to receive full review, the editors must be convinced that it is an important advance in for the field. The Impact Statement is not a restating of the abstract. It should address the following: Why is the work submitted important to the field? How does the work submitted advance the field? What new information does this work impart to the field? How does this new information impact the field? Experimental Biology and Medicine journal, author guidelines

Typically the impact statement will be shorter than the Abstract, around 150 words.

Defining the study’s significance is helpful not just for the impact statement (if the journal asks for one) but also for building a more compelling argument throughout your submission. For instance, usually you’ll start the Discussion section of a paper by highlighting the research significance of your work. You’ll also include a short description in your Abstract too.

How to describe the research significance of a study, with examples

Whether you’re writing a thesis or a journal article, the approach to writing about the significance of a study are broadly the same.

I’d therefore suggest using the questions above as a starting point to base your statements on.

- Why is the work submitted important to the field?

- How does the work submitted advance the field?

- What new information does this work impart to the field?

- How does this new information impact the field?

Answer those questions and you’ll have a much clearer idea of the research significance of your work.

When describing it, try to clearly state what is novel about your study’s contribution to the literature. Then go on to discuss what impact it could have on progressing the field along with recommendations for future work.

Potential sentence starters

If you’re not sure where to start, why not set a 10 minute timer and have a go at trying to finish a few of the following sentences. Not sure on what to put? Have a chat to your supervisor or lab mates and they may be able to suggest some ideas.

- This study is important to the field because…

- These findings advance the field by…

- Our results highlight the importance of…

- Our discoveries impact the field by…

Now you’ve had a go let’s have a look at some real life examples.

Statement of significance examples

A statement of significance / impact:

Impact Statement This review highlights the historical development of the concept of “ideal protein” that began in the 1950s and 1980s for poultry and swine diets, respectively, and the major conceptual deficiencies of the long-standing concept of “ideal protein” in animal nutrition based on recent advances in amino acid (AA) metabolism and functions. Nutritionists should move beyond the “ideal protein” concept to consider optimum ratios and amounts of all proteinogenic AAs in animal foods and, in the case of carnivores, also taurine. This will help formulate effective low-protein diets for livestock, poultry, and fish, while sustaining global animal production. Because they are not only species of agricultural importance, but also useful models to study the biology and diseases of humans as well as companion (e.g. dogs and cats), zoo, and extinct animals in the world, our work applies to a more general readership than the nutritionists and producers of farm animals. Wu G, Li P. The “ideal protein” concept is not ideal in animal nutrition. Experimental Biology and Medicine . 2022;247(13):1191-1201. doi: 10.1177/15353702221082658

And the same type of section but this time called “Advances in knowledge”:

Advances in knowledge: According to the MY-RADs criteria, size measurements of focal lesions in MRI are now of relevance for response assessment in patients with monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Size changes of 1 or 2 mm are frequently observed due to uncertainty of the measurement only, while the actual focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Size changes of at least 6 mm or more in T 1 weighted or T 2 weighted short tau inversion recovery sequences occur in only 5% or less of cases when the focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Wennmann M, Grözinger M, Weru V, et al. Test-retest, inter- and intra-rater reproducibility of size measurements of focal bone marrow lesions in MRI in patients with multiple myeloma [published online ahead of print, 2023 Apr 12]. Br J Radiol . 2023;20220745. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220745

Other examples of research significance

Moving beyond the formal statement of significance, here is how you can describe research significance more broadly within your paper.

Describing research impact in an Abstract of a paper:

Three-dimensional visualisation and quantification of the chondrocyte population within articular cartilage can be achieved across a field of view of several millimetres using laboratory-based micro-CT. The ability to map chondrocytes in 3D opens possibilities for research in fields from skeletal development through to medical device design and treatment of cartilage degeneration. Conclusions section of the abstract in my first paper .

In the Discussion section of a paper:

We report for the utility of a standard laboratory micro-CT scanner to visualise and quantify features of the chondrocyte population within intact articular cartilage in 3D. This study represents a complimentary addition to the growing body of evidence supporting the non-destructive imaging of the constituents of articular cartilage. This offers researchers the opportunity to image chondrocyte distributions in 3D without specialised synchrotron equipment, enabling investigations such as chondrocyte morphology across grades of cartilage damage, 3D strain mapping techniques such as digital volume correlation to evaluate mechanical properties in situ , and models for 3D finite element analysis in silico simulations. This enables an objective quantification of chondrocyte distribution and morphology in three dimensions allowing greater insight for investigations into studies of cartilage development, degeneration and repair. One such application of our method, is as a means to provide a 3D pattern in the cartilage which, when combined with digital volume correlation, could determine 3D strain gradient measurements enabling potential treatment and repair of cartilage degeneration. Moreover, the method proposed here will allow evaluation of cartilage implanted with tissue engineered scaffolds designed to promote chondral repair, providing valuable insight into the induced regenerative process. The Discussion section of the paper is laced with references to research significance.

How is longer term research significance measured?

Looking beyond writing impact statements within papers, sometimes you’ll want to quantify the long term research significance of your work. For instance when applying for jobs.

The most obvious measure of a study’s long term research significance is the number of citations it receives from future publications. The thinking is that a study which receives more citations will have had more research impact, and therefore significance , than a study which received less citations. Citations can give a broad indication of how useful the work is to other researchers but citations aren’t really a good measure of significance.

Bear in mind that us researchers can be lazy folks and sometimes are simply looking to cite the first paper which backs up one of our claims. You can find studies which receive a lot of citations simply for packaging up the obvious in a form which can be easily found and referenced, for instance by having a catchy or optimised title.

Likewise, research activity varies wildly between fields. Therefore a certain study may have had a big impact on a particular field but receive a modest number of citations, simply because not many other researchers are working in the field.

Nevertheless, citations are a standard measure of significance and for better or worse it remains impressive for someone to be the first author of a publication receiving lots of citations.

Other measures for the research significance of a study include:

- Accolades: best paper awards at conferences, thesis awards, “most downloaded” titles for articles, press coverage.

- How much follow-on research the study creates. For instance, part of my PhD involved a novel material initially developed by another PhD student in the lab. That PhD student’s research had unlocked lots of potential new studies and now lots of people in the group were using the same material and developing it for different applications. The initial study may not receive a high number of citations yet long term it generated a lot of research activity.

That covers research significance, but you’ll often want to consider other types of significance for your study and we’ll cover those next.

Statistical Significance

What is the statistical significance of a study.

Often as part of a study you’ll carry out statistical tests and then state the statistical significance of your findings: think p-values eg <0.05. It is useful to describe the outcome of these tests within your report or paper, to give a measure of statistical significance.

Effectively you are trying to show whether the performance of your innovation is actually better than a control or baseline and not just chance. Statistical significance deserves a whole other post so I won’t go into a huge amount of depth here.

Things that make publication in The BMJ impossible or unlikely Internal validity/robustness of the study • It had insufficient statistical power, making interpretation difficult; • Lack of statistical power; The British Medical Journal’s guide for authors

Calculating statistical significance isn’t always necessary (or valid) for a study, such as if you have a very small number of samples, but it is a very common requirement for scientific articles.

Writing a journal article? Check the journal’s guide for authors to see what they expect. Generally if you have approximately five or more samples or replicates it makes sense to start thinking about statistical tests. Speak to your supervisor and lab mates for advice, and look at other published articles in your field.

How is statistical significance measured?

Statistical significance is quantified using p-values . Depending on your study design you’ll choose different statistical tests to compute the p-value.

A p-value of 0.05 is a common threshold value. The 0.05 means that there is a 1/20 chance that the difference in performance you’re reporting is just down to random chance.

- p-values above 0.05 mean that the result isn’t statistically significant enough to be trusted: it is too likely that the effect you’re showing is just luck.

- p-values less than or equal to 0.05 mean that the result is statistically significant. In other words: unlikely to just be chance, which is usually considered a good outcome.

Low p-values (eg p = 0.001) mean that it is highly unlikely to be random chance (1/1000 in the case of p = 0.001), therefore more statistically significant.

It is important to clarify that, although low p-values mean that your findings are statistically significant, it doesn’t automatically mean that the result is scientifically important. More on that in the next section on research significance.

How to describe the statistical significance of your study, with examples

In the first paper from my PhD I ran some statistical tests to see if different staining techniques (basically dyes) increased how well you could see cells in cow tissue using micro-CT scanning (a 3D imaging technique).

In your methods section you should mention the statistical tests you conducted and then in the results you will have statements such as:

Between mediums for the two scan protocols C/N [contrast to noise ratio] was greater for EtOH than the PBS in both scanning methods (both p < 0.0001) with mean differences of 1.243 (95% CI [confidence interval] 0.709 to 1.778) for absorption contrast and 6.231 (95% CI 5.772 to 6.690) for propagation contrast. … Two repeat propagation scans were taken of samples from the PTA-stained groups. No difference in mean C/N was found with either medium: PBS had a mean difference of 0.058 ( p = 0.852, 95% CI -0.560 to 0.676), EtOH had a mean difference of 1.183 ( p = 0.112, 95% CI 0.281 to 2.648). From the Results section of my first paper, available here . Square brackets added for this post to aid clarity.

From this text the reader can infer from the first paragraph that there was a statistically significant difference in using EtOH compared to PBS (really small p-value of <0.0001). However, from the second paragraph, the difference between two repeat scans was statistically insignificant for both PBS (p = 0.852) and EtOH (p = 0.112).

By conducting these statistical tests you have then earned your right to make bold statements, such as these from the discussion section:

Propagation phase-contrast increases the contrast of individual chondrocytes [cartilage cells] compared to using absorption contrast. From the Discussion section from the same paper.

Without statistical tests you have no evidence that your results are not just down to random chance.

Beyond describing the statistical significance of a study in the main body text of your work, you can also show it in your figures.

In figures such as bar charts you’ll often see asterisks to represent statistical significance, and “n.s.” to show differences between groups which are not statistically significant. Here is one such figure, with some subplots, from the same paper:

In this example an asterisk (*) between two bars represents p < 0.05. Two asterisks (**) represents p < 0.001 and three asterisks (***) represents p < 0.0001. This should always be stated in the caption of your figure since the values that each asterisk refers to can vary.

Now that we know if a study is showing statistically and research significance, let’s zoom out a little and consider the potential for commercial significance.

Commercial and Industrial Significance

What are commercial and industrial significance.

Moving beyond significance in relation to academia, your research may also have commercial or economic significance.

Simply put:

- Commercial significance: could the research be commercialised as a product or service? Perhaps the underlying technology described in your study could be licensed to a company or you could even start your own business using it.

- Industrial significance: more widely than just providing a product which could be sold, does your research provide insights which may affect a whole industry? Such as: revealing insights or issues with current practices, performance gains you don’t want to commercialise (e.g. solar power efficiency), providing suggested frameworks or improvements which could be employed industry-wide.

I’ve grouped these two together because there can certainly be overlap. For instance, perhaps your new technology could be commercialised whilst providing wider improvements for the whole industry.

Commercial and industrial significance are not relevant to most studies, so only write about it if you and your supervisor can think of reasonable routes to your work having an impact in these ways.

How are commercial and industrial significance measured?

Unlike statistical and research significances, the measures of commercial and industrial significance can be much more broad.

Here are some potential measures of significance:

Commercial significance:

- How much value does your technology bring to potential customers or users?

- How big is the potential market and how much revenue could the product potentially generate?

- Is the intellectual property protectable? i.e. patentable, or if not could the novelty be protected with trade secrets: if so publish your method with caution!

- If commercialised, could the product bring employment to a geographical area?

Industrial significance:

What impact could it have on the industry? For instance if you’re revealing an issue with something, such as unintended negative consequences of a drug , what does that mean for the industry and the public? This could be:

- Reduced overhead costs

- Better safety

- Faster production methods

- Improved scaleability

How to describe the commercial and industrial significance of a study, with examples

Commercial significance.

If your technology could be commercially viable, and you’ve got an interest in commercialising it yourself, it is likely that you and your university may not want to immediately publish the study in a journal.

You’ll probably want to consider routes to exploiting the technology and your university may have a “technology transfer” team to help researchers navigate the various options.

However, if instead of publishing a paper you’re submitting a thesis or dissertation then it can be useful to highlight the commercial significance of your work. In this instance you could include statements of commercial significance such as:

The measurement technology described in this study provides state of the art performance and could enable the development of low cost devices for aerospace applications. An example of commercial significance I invented for this post

Industrial significance

First, think about the industrial sectors who could benefit from the developments described in your study.

For example if you’re working to improve battery efficiency it is easy to think of how it could lead to performance gains for certain industries, like personal electronics or electric vehicles. In these instances you can describe the industrial significance relatively easily, based off your findings.

For example:

By utilising abundant materials in the described battery fabrication process we provide a framework for battery manufacturers to reduce dependence on rare earth components. Again, an invented example

For other technologies there may well be industrial applications but they are less immediately obvious and applicable. In these scenarios the best you can do is to simply reframe your research significance statement in terms of potential commercial applications in a broad way.

As a reminder: not all studies should address industrial significance, so don’t try to invent applications just for the sake of it!

Societal Significance

What is the societal significance of a study.

The most broad category of significance is the societal impact which could stem from it.

If you’re working in an applied field it may be quite easy to see a route for your research to impact society. For others, the route to societal significance may be less immediate or clear.

Studies can help with big issues facing society such as:

- Medical applications : vaccines, surgical implants, drugs, improving patient safety. For instance this medical device and drug combination I worked on which has a very direct route to societal significance.

- Political significance : Your research may provide insights which could contribute towards potential changes in policy or better understanding of issues facing society.

- Public health : for instance COVID-19 transmission and related decisions.

- Climate change : mitigation such as more efficient solar panels and lower cost battery solutions, and studying required adaptation efforts and technologies. Also, better understanding around related societal issues, for instance this study on the effects of temperature on hate speech.

How is societal significance measured?

Societal significance at a high level can be quantified by the size of its potential societal effect. Just like a lab risk assessment, you can think of it in terms of probability (or how many people it could help) and impact magnitude.

Societal impact = How many people it could help x the magnitude of the impact

Think about how widely applicable the findings are: for instance does it affect only certain people? Then think about the potential size of the impact: what kind of difference could it make to those people?

Between these two metrics you can get a pretty good overview of the potential societal significance of your research study.

How to describe the societal significance of a study, with examples

Quite often the broad societal significance of your study is what you’re setting the scene for in your Introduction. In addition to describing the existing literature, it is common to for the study’s motivation to touch on its wider impact for society.

For those of us working in healthcare research it is usually pretty easy to see a path towards societal significance.

Our CLOUT model has state-of-the-art performance in mortality prediction, surpassing other competitive NN models and a logistic regression model … Our results show that the risk factors identified by the CLOUT model agree with physicians’ assessment, suggesting that CLOUT could be used in real-world clinicalsettings. Our results strongly support that CLOUT may be a useful tool to generate clinical prediction models, especially among hospitalized and critically ill patient populations. Learning Latent Space Representations to Predict Patient Outcomes: Model Development and Validation

In other domains the societal significance may either take longer or be more indirect, meaning that it can be more difficult to describe the societal impact.

Even so, here are some examples I’ve found from studies in non-healthcare domains:

We examined food waste as an initial investigation and test of this methodology, and there is clear potential for the examination of not only other policy texts related to food waste (e.g., liability protection, tax incentives, etc.; Broad Leib et al., 2020) but related to sustainable fishing (Worm et al., 2006) and energy use (Hawken, 2017). These other areas are of obvious relevance to climate change… AI-Based Text Analysis for Evaluating Food Waste Policies

The continued development of state-of-the art NLP tools tailored to climate policy will allow climate researchers and policy makers to extract meaningful information from this growing body of text, to monitor trends over time and administrative units, and to identify potential policy improvements. BERT Classification of Paris Agreement Climate Action Plans

Top Tips For Identifying & Writing About the Significance of Your Study

- Writing a thesis? Describe the significance of your study in the Introduction and the Conclusion .

- Submitting a paper? Read the journal’s guidelines. If you’re writing a statement of significance for a journal, make sure you read any guidance they give for what they’re expecting.

- Take a step back from your research and consider your study’s main contributions.

- Read previously published studies in your field . Use this for inspiration and ideas on how to describe the significance of your own study

- Discuss the study with your supervisor and potential co-authors or collaborators and brainstorm potential types of significance for it.

Now you’ve finished reading up on the significance of a study you may also like my how-to guide for all aspects of writing your first research paper .

Writing an academic journal paper

I hope that you’ve learned something useful from this article about the significance of a study. If you have any more research-related questions let me know, I’m here to help.

To gain access to my content library you can subscribe below for free:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

How to Build a LinkedIn Student Profile

18th October 2024 18th October 2024

How to Plan a Research Visit

13th September 2024 13th September 2024

The Five Most Powerful Lessons I Learned During My PhD

8th August 2024 8th August 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

How To Write Significance of the Study (With Examples)

Whether you’re writing a research paper or thesis, a portion called Significance of the Study ensures your readers understand the impact of your work. Learn how to effectively write this vital part of your research paper or thesis through our detailed steps, guidelines, and examples.

Related: How to Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research

Table of Contents

What is the significance of the study.

The Significance of the Study presents the importance of your research. It allows you to prove the study’s impact on your field of research, the new knowledge it contributes, and the people who will benefit from it.

Related: How To Write Scope and Delimitation of a Research Paper (With Examples)

Where Should I Put the Significance of the Study?

The Significance of the Study is part of the first chapter or the Introduction. It comes after the research’s rationale, problem statement, and hypothesis.

Related: How to Make Conceptual Framework (with Examples and Templates)

Why Should I Include the Significance of the Study?

The purpose of the Significance of the Study is to give you space to explain to your readers how exactly your research will be contributing to the literature of the field you are studying 1 . It’s where you explain why your research is worth conducting and its significance to the community, the people, and various institutions.

How To Write Significance of the Study: 5 Steps

Below are the steps and guidelines for writing your research’s Significance of the Study.

1. Use Your Research Problem as a Starting Point

Your problem statement can provide clues to your research study’s outcome and who will benefit from it 2 .

Ask yourself, “How will the answers to my research problem be beneficial?”. In this manner, you will know how valuable it is to conduct your study.

Let’s say your research problem is “What is the level of effectiveness of the lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) in lowering the blood glucose level of Swiss mice (Mus musculus)?”

Discovering a positive correlation between the use of lemongrass and lower blood glucose level may lead to the following results:

- Increased public understanding of the plant’s medical properties;

- Higher appreciation of the importance of lemongrass by the community;

- Adoption of lemongrass tea as a cheap, readily available, and natural remedy to lower their blood glucose level.

Once you’ve zeroed in on the general benefits of your study, it’s time to break it down into specific beneficiaries.

2. State How Your Research Will Contribute to the Existing Literature in the Field

Think of the things that were not explored by previous studies. Then, write how your research tackles those unexplored areas. Through this, you can convince your readers that you are studying something new and adding value to the field.

3. Explain How Your Research Will Benefit Society

In this part, tell how your research will impact society. Think of how the results of your study will change something in your community.

For example, in the study about using lemongrass tea to lower blood glucose levels, you may indicate that through your research, the community will realize the significance of lemongrass and other herbal plants. As a result, the community will be encouraged to promote the cultivation and use of medicinal plants.

4. Mention the Specific Persons or Institutions Who Will Benefit From Your Study

Using the same example above, you may indicate that this research’s results will benefit those seeking an alternative supplement to prevent high blood glucose levels.

5. Indicate How Your Study May Help Future Studies in the Field

You must also specifically indicate how your research will be part of the literature of your field and how it will benefit future researchers. In our example above, you may indicate that through the data and analysis your research will provide, future researchers may explore other capabilities of herbal plants in preventing different diseases.

Tips and Warnings

- Think ahead . By visualizing your study in its complete form, it will be easier for you to connect the dots and identify the beneficiaries of your research.

- Write concisely. Make it straightforward, clear, and easy to understand so that the readers will appreciate the benefits of your research. Avoid making it too long and wordy.

- Go from general to specific . Like an inverted pyramid, you start from above by discussing the general contribution of your study and become more specific as you go along. For instance, if your research is about the effect of remote learning setup on the mental health of college students of a specific university , you may start by discussing the benefits of the research to society, to the educational institution, to the learning facilitators, and finally, to the students.

- Seek help . For example, you may ask your research adviser for insights on how your research may contribute to the existing literature. If you ask the right questions, your research adviser can point you in the right direction.

- Revise, revise, revise. Be ready to apply necessary changes to your research on the fly. Unexpected things require adaptability, whether it’s the respondents or variables involved in your study. There’s always room for improvement, so never assume your work is done until you have reached the finish line.

Significance of the Study Examples

This section presents examples of the Significance of the Study using the steps and guidelines presented above.

Example 1: STEM-Related Research

Research Topic: Level of Effectiveness of the Lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ) Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice ( Mus musculus ).

Significance of the Study .

This research will provide new insights into the medicinal benefit of lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ), specifically on its hypoglycemic ability.

Through this research, the community will further realize promoting medicinal plants, especially lemongrass, as a preventive measure against various diseases. People and medical institutions may also consider lemongrass tea as an alternative supplement against hyperglycemia.

Moreover, the analysis presented in this study will convey valuable information for future research exploring the medicinal benefits of lemongrass and other medicinal plants.

Example 2: Business and Management-Related Research

Research Topic: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Social Media Marketing of Small Clothing Enterprises.

Significance of the Study:

By comparing the two marketing strategies presented by this research, there will be an expansion on the current understanding of the firms on these marketing strategies in terms of cost, acceptability, and sustainability. This study presents these marketing strategies for small clothing enterprises, giving them insights into which method is more appropriate and valuable for them.

Specifically, this research will benefit start-up clothing enterprises in deciding which marketing strategy they should employ. Long-time clothing enterprises may also consider the result of this research to review their current marketing strategy.

Furthermore, a detailed presentation on the comparison of the marketing strategies involved in this research may serve as a tool for further studies to innovate the current method employed in the clothing Industry.

Example 3: Social Science -Related Research.

Research Topic: Divide Et Impera : An Overview of How the Divide-and-Conquer Strategy Prevailed on Philippine Political History.

Significance of the Study :

Through the comprehensive exploration of this study on Philippine political history, the influence of the Divide et Impera, or political decentralization, on the political discernment across the history of the Philippines will be unraveled, emphasized, and scrutinized. Moreover, this research will elucidate how this principle prevailed until the current political theatre of the Philippines.

In this regard, this study will give awareness to society on how this principle might affect the current political context. Moreover, through the analysis made by this study, political entities and institutions will have a new approach to how to deal with this principle by learning about its influence in the past.

In addition, the overview presented in this research will push for new paradigms, which will be helpful for future discussion of the Divide et Impera principle and may lead to a more in-depth analysis.

Example 4: Humanities-Related Research

Research Topic: Effectiveness of Meditation on Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students.

Significance of the Study:

This research will provide new perspectives in approaching anxiety issues of college students through meditation.

Specifically, this research will benefit the following:

Community – this study spreads awareness on recognizing anxiety as a mental health concern and how meditation can be a valuable approach to alleviating it.

Academic Institutions and Administrators – through this research, educational institutions and administrators may promote programs and advocacies regarding meditation to help students deal with their anxiety issues.

Mental health advocates – the result of this research will provide valuable information for the advocates to further their campaign on spreading awareness on dealing with various mental health issues, including anxiety, and how to stop stigmatizing those with mental health disorders.

Parents – this research may convince parents to consider programs involving meditation that may help the students deal with their anxiety issues.

Students will benefit directly from this research as its findings may encourage them to consider meditation to lower anxiety levels.

Future researchers – this study covers information involving meditation as an approach to reducing anxiety levels. Thus, the result of this study can be used for future discussions on the capabilities of meditation in alleviating other mental health concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is the difference between the significance of the study and the rationale of the study.

Both aim to justify the conduct of the research. However, the Significance of the Study focuses on the specific benefits of your research in the field, society, and various people and institutions. On the other hand, the Rationale of the Study gives context on why the researcher initiated the conduct of the study.

Let’s take the research about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Levels of College Students as an example. Suppose you are writing about the Significance of the Study. In that case, you must explain how your research will help society, the academic institution, and students deal with anxiety issues through meditation. Meanwhile, for the Rationale of the Study, you may state that due to the prevalence of anxiety attacks among college students, you’ve decided to make it the focal point of your research work.

2. What is the difference between Justification and the Significance of the Study?

In Justification, you express the logical reasoning behind the conduct of the study. On the other hand, the Significance of the Study aims to present to your readers the specific benefits your research will contribute to the field you are studying, community, people, and institutions.

Suppose again that your research is about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students. Suppose you are writing the Significance of the Study. In that case, you may state that your research will provide new insights and evidence regarding meditation’s ability to reduce college students’ anxiety levels. Meanwhile, you may note in the Justification that studies are saying how people used meditation in dealing with their mental health concerns. You may also indicate how meditation is a feasible approach to managing anxiety using the analysis presented by previous literature.

3. How should I start my research’s Significance of the Study section?

– This research will contribute… – The findings of this research… – This study aims to… – This study will provide… – Through the analysis presented in this study… – This study will benefit…

Moreover, you may start the Significance of the Study by elaborating on the contribution of your research in the field you are studying.

4. What is the difference between the Purpose of the Study and the Significance of the Study?

The Purpose of the Study focuses on why your research was conducted, while the Significance of the Study tells how the results of your research will benefit anyone.

Suppose your research is about the Effectiveness of Lemongrass Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice . You may include in your Significance of the Study that the research results will provide new information and analysis on the medical ability of lemongrass to solve hyperglycemia. Meanwhile, you may include in your Purpose of the Study that your research wants to provide a cheaper and natural way to lower blood glucose levels since commercial supplements are expensive.

5. What is the Significance of the Study in Tagalog?

In Filipino research, the Significance of the Study is referred to as Kahalagahan ng Pag-aaral.

- Draft your Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from http://dissertationedd.usc.edu/draft-your-significance-of-the-study.html

- Regoniel, P. (2015). Two Tips on How to Write the Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from https://simplyeducate.me/2015/02/09/significance-of-the-study/

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula graduated Cum Laude with a degree of Bachelor of Science in Economics from the University of the Philippines Diliman. He is also a nominee for the 2023 Gerardo Sicat Award for Best Undergraduate Thesis in Economics. He is currently a freelance content writer with writing experience related to technology, artificial intelligence, ergonomic products, and education. Kyle loves cats, mathematics, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What is the Significance of the Study?

- By DiscoverPhDs

- August 25, 2020

- what the significance of the study means,

- why it’s important to include in your research work,

- where you would include it in your paper, thesis or dissertation,

- how you write one

- and finally an example of a well written section about the significance of the study.

What does Significance of the Study mean?

The significance of the study is a written statement that explains why your research was needed. It’s a justification of the importance of your work and impact it has on your research field, it’s contribution to new knowledge and how others will benefit from it.

Why is the Significance of the Study important?

The significance of the study, also known as the rationale of the study, is important to convey to the reader why the research work was important. This may be an academic reviewer assessing your manuscript under peer-review, an examiner reading your PhD thesis, a funder reading your grant application or another research group reading your published journal paper. Your academic writing should make clear to the reader what the significance of the research that you performed was, the contribution you made and the benefits of it.

How do you write the Significance of the Study?

When writing this section, first think about where the gaps in knowledge are in your research field. What are the areas that are poorly understood with little or no previously published literature? Or what topics have others previously published on that still require further work. This is often referred to as the problem statement.

The introduction section within the significance of the study should include you writing the problem statement and explaining to the reader where the gap in literature is.

Then think about the significance of your research and thesis study from two perspectives: (1) what is the general contribution of your research on your field and (2) what specific contribution have you made to the knowledge and who does this benefit the most.

For example, the gap in knowledge may be that the benefits of dumbbell exercises for patients recovering from a broken arm are not fully understood. You may have performed a study investigating the impact of dumbbell training in patients with fractures versus those that did not perform dumbbell exercises and shown there to be a benefit in their use. The broad significance of the study would be the improvement in the understanding of effective physiotherapy methods. Your specific contribution has been to show a significant improvement in the rate of recovery in patients with broken arms when performing certain dumbbell exercise routines.

This statement should be no more than 500 words in length when written for a thesis. Within a research paper, the statement should be shorter and around 200 words at most.

Significance of the Study: An example

Building on the above hypothetical academic study, the following is an example of a full statement of the significance of the study for you to consider when writing your own. Keep in mind though that there’s no single way of writing the perfect significance statement and it may well depend on the subject area and the study content.

Here’s another example to help demonstrate how a significance of the study can also be applied to non-technical fields:

The significance of this research lies in its potential to inform clinical practices and patient counseling. By understanding the psychological outcomes associated with non-surgical facial aesthetics, practitioners can better guide their patients in making informed decisions about their treatment plans. Additionally, this study contributes to the body of academic knowledge by providing empirical evidence on the effects of these cosmetic procedures, which have been largely anecdotal up to this point.

The statement of the significance of the study is used by students and researchers in academic writing to convey the importance of the research performed; this section is written at the end of the introduction and should describe the specific contribution made and who it benefits.

There’s no doubt about it – writing can be difficult. Whether you’re writing the first sentence of a paper or a grant proposal, it’s easy

Considering whether to do an MBA or a PhD? If so, find out what their differences are, and more importantly, which one is better suited for you.

An academic transcript gives a breakdown of each module you studied for your degree and the mark that you were awarded.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

A science investigatory project is a science-based research project or study that is performed by school children in a classroom, exhibition or science fair.

An abstract and introduction are the first two sections of your paper or thesis. This guide explains the differences between them and how to write them.

Emma is a third year PhD student at the University of Rhode Island. Her research focuses on the physiological and genomic response to climate change stressors.

Rebecca recently finished her PhD at the University of York. Her research investigated the adaptations that occur in the symbiosis between the tsetse fly and its bacterial microbiome.

Join Thousands of Students

Significance of a Study: Revisiting the “So What” Question

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 December 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- James Hiebert 6 ,

- Jinfa Cai 7 ,

- Stephen Hwang 7 ,

- Anne K Morris 6 &

- Charles Hohensee 6

Part of the book series: Research in Mathematics Education ((RME))

38k Accesses

Every researcher wants their study to matter—to make a positive difference for their professional communities. To ensure your study matters, you can formulate clear hypotheses and choose methods that will test them well, as described in Chaps. 1, 2, 3 and 4. You can go further, however, by considering some of the terms commonly used to describe the importance of studies, terms like significance, contributions, and implications. As you clarify for yourself the meanings of these terms, you learn that whether your study matters depends on how convincingly you can argue for its importance. Perhaps most surprising is that convincing others of its importance rests with the case you make before the data are ever gathered. The importance of your hypotheses should be apparent before you test them. Are your predictions about things the profession cares about? Can you make them with a striking degree of precision? Are the rationales that support them compelling? You are answering the “So what?” question as you formulate hypotheses and design tests of them. This means you can control the answer. You do not need to cross your fingers and hope as you collect data.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Part I. Setting the Groundwork

One of the most common questions asked of researchers is “So what?” What difference does your study make? Why are the findings important? The “so what” question is one of the most basic questions, often perceived by novice researchers as the most difficult question to answer. Indeed, addressing the “so what” question continues to challenge even experienced researchers. It is not always easy to articulate a convincing argument for the importance of your work. It can be especially difficult to describe its importance without falling into the trap of making claims that reach beyond the data.

That this issue is a challenge for researchers is illustrated by our analysis of reviewer comments for JRME . About one-third of the reviews for manuscripts that were ultimately rejected included concerns about the importance of the study. Said another way, reviewers felt the “So what?” question had not been answered. To paraphrase one journal reviewer, “The manuscript left me unsure of what the contribution of this work to the field’s knowledge is, and therefore I doubt its significance.” We expect this is a frequent concern of reviewers for all research journals.

Our goal in this chapter is to help you navigate the pressing demands of journal reviewers, editors, and readers for demonstrating the importance of your work while staying within the bounds of acceptable claims based on your results. We will begin by reviewing what we have said about these issues in previous chapters. We will then clarify one of the confusing aspects of developing appropriate arguments—the absence of consensus definitions of key terms such as significance, contributions, and implications. Based on the definitions we propose, we will examine the critical role of alignment for realizing the potential significance of your study. Because the importance of your study is communicated through your evolving research paper, we will fold suggestions for writing your paper into the discussion of creating and executing your study.

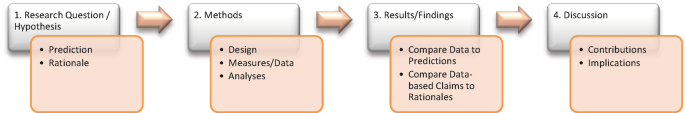

We laid the groundwork in Chap. 1 for what we consider to be important research in education:

In our view, the ultimate goal of education is to offer all students the best possible learning opportunities. So, we believe the ultimate purpose of scientific inquiry in education is to support the improvement of learning opportunities for all students…. If there is no way to imagine a connection to improving learning opportunities for students, even a distant connection, we recommend you reconsider whether it is an important hypothesis within the education community.

Of course, you might prefer another “ultimate purpose” for research in education. That’s fine. The critical point is that the argument for the importance of the hypotheses you are testing should be connected to the value of a long-term goal you can describe. As long as most of the educational community agrees with this goal, and you can show how testing your hypotheses will move the field forward to achieving this goal, you will have developed a convincing argument for the importance of your work.

In Chap. 2 , we argued the importance of your hypotheses can and should be established before you collect data. Your theoretical framework should carry the weight of your argument because it should describe how your hypotheses will extend what is already known. Your methods should then show that you will test your hypotheses in an appropriate way—in a way that will allow you to detect how the results did, and did not, confirm the hypotheses. This will, in turn, allow you to formulate revised hypotheses. We described establishing the importance of your study by saying, “The importance can come from the fact that, based on the results, you will be able to offer revised hypotheses that help the field better understand an issue relevant for improving all students’ learning opportunities.”

The ideas from Chaps. 1 , 2 , and 3 go a long way toward setting the parameters for what counts as an important study and how its importance can be determined. Chapter 4 focused on ensuring that the importance of a study can be realized. The next section fills in the details by proposing definitions for the most common terms used to claim importance: significance, contributions, and implications.

You might notice that we do not have a chapter dedicated to discussing the presentation of the findings—that is, a “results” chapter. We do not mean to imply that presenting results is trivial. However, we believe that if you follow our recommendations for writing your evolving research paper, presenting the results will be quite straightforward. The key is to present your results so they can be most easily compared with your predictions. This means, among other things, organizing your presentation of results according to your earlier presentation of hypotheses.

Part II. Clarifying Importance by Revisiting the Definitions of Key Terms

What does it mean to say your findings are significant? Statistical significance is clear. There are widely accepted standards for determining the statistical significance of findings. But what about educational significance? Is this the same as claiming that your study makes an important contribution? Or, that your study has important implications? Different researchers might answer these questions in different ways. When key terms like these are overused, their definitions gradually broaden or shift, and they can lose their meaning. That is unfortunate, because it creates confusion about how to develop claims for the importance of a study.

By clarifying the definitions, we hope to clarify what is required to claim that a study is significant , that it makes a contribution , and that it has important implications . Not everyone defines the terms as we do. Our definitions are probably a bit narrower or more targeted than those you may encounter elsewhere. Depending on where you want to publish your study, you may want to adapt your use of these terms to match more closely the expectations of a particular journal. But the way we define and address these terms is not antithetical to common uses. And we believe ridding the terms of unnecessary overlap allows us to discriminate among different key concepts with respect to claims for the importance of research studies. It is not necessary to define the terms exactly as we have, but it is critical that the ideas embedded in our definitions be distinguished and that all of them be taken into account when examining the importance of a study.

We will use the following definitions:

Significance: The importance of the problem, questions, and/or hypotheses for improving the learning opportunities for all students (you can substitute a different long-term goal if its value is widely shared). Significance can be determined before data are gathered. Significance is an attribute of the research problem , not the research findings .

Contributions : The value of the findings for revising the hypotheses, making clear what has been learned, what is now better understood.

Implications : Deductions about what can be concluded from the findings that are not already included in “contributions.” The most common deductions in educational research are for improving educational practice. Deductions for research practice that are not already defined as contributions are often suggestions about research methods that are especially useful or methods to avoid.

Significance

The significance of a study is built by formulating research questions and hypotheses you connect through a careful argument to a long-term goal of widely shared value (e.g., improving learning opportunities for all students). Significance applies both to the domain in which your study is located and to your individual study. The significance of the domain is established by choosing a goal of widely shared value and then identifying a domain you can show is connected to achieving the goal. For example, if the goal to which your study contributes is improving the learning opportunities for all students, your study might aim to understand more fully how things work in a domain such as teaching for conceptual understanding, or preparing teachers to attend to all students, or designing curricula to support all learners, or connecting learning opportunities to particular learning outcomes.

The significance of your individual study is something you build ; it is not predetermined or self-evident. Significance of a study is established by making a case for it, not by simply choosing hypotheses everyone already thinks are important. Although you might believe the significance of your study is obvious, readers will need to be convinced.

Significance is something you develop in your evolving research paper. The theoretical framework you present connects your study to what has been investigated previously. Your argument for significance of the domain comes from the significance of the line of research of which your study is a part. The significance of your study is developed by showing, through the presentation of your framework, how your study advances this line of research. This means the lion’s share of your answer to the “So what?” question will be developed as part of your theoretical framework.

Although defining significance as located in your paper prior to presenting results is not a definition universally shared among educational researchers, it is becoming an increasingly common view. In fact, there is movement toward evaluating the significance of a study based only on the first sections of a research paper—the sections prior to the results (Makel et al., 2021 ).

In addition to addressing the “So what?” question, your theoretical framework can address another common concern often voiced by readers: “What is so interesting? I could have predicted those results.” Predictions do not need to be surprising to be interesting and significant. The significance comes from the rationales that show how the predictions extend what is currently known. It is irrelevant how many researchers could have made the predictions. What makes a study significant is that the theoretical framework and the predictions make clear how the study will increase the field’s understanding toward achieving a goal of shared value.

An important consequence of interpreting significance as a carefully developed argument for the importance of your research study within a larger domain is that it reveals the advantage of conducting a series of connected studies rather than single, disconnected studies. Building the significance of a research study requires time and effort. Once you have established significance for a particular study, you can build on this same argument for related studies. This saves time, allows you to continue to refine your argument across studies, and increases the likelihood your studies will contribute to the field.

Contributions

As we have noted, in fields as complicated as education, it is unlikely that your predictions will be entirely accurate. If the problem you are investigating is significant, the hypotheses will be formulated in such a way that they extend a line of research to understand more deeply phenomena related to students’ learning opportunities or another goal of shared value. Often, this means investigating the conditions under which phenomena occur. This gets complicated very quickly, so the data you gather will likely differ from your predictions in a variety of ways. The contributions your study makes will depend on how you interpret these results in light of the original hypotheses.

Contributions Emerge from Revisions to your Hypotheses

We view interpreting results as a process of comparing the data with the predictions and then examining the way in which hypotheses should be revised to more fully account for the results. Revising will almost always be warranted because, as we noted, predictions are unlikely to be entirely accurate. For example, if researchers expect Outcome A to occur under specified conditions but find that it does not occur to the extent predicted or actually does occur but without all the conditions, they must ask what changes to the hypotheses are needed to predict more accurately the conditions under which Outcome A occurred. Are there, for example, essential conditions that were not anticipated and that should be included in the revised hypotheses?

Consider an example from a recently published study (Wang et al., 2021 ). A team of researchers investigated the following research question: “How are students’ perceptions of their parents’ expectations related to students’ mathematics-related beliefs and their perceived mathematics achievement?” The researchers predicted that students’ perceptions of their parents’ expectations would be highly related to students’ mathematics-related beliefs and their perceived mathematics achievement. The rationale was based largely on prior research that had consistently found parents’ general educational expectations to be highly correlated with students’ achievement.

The findings showed that Chinese high school students’ perceptions of their parents’ educational expectations were positively related to these students’ mathematics-related beliefs. In other words, students who believed their parents expected them to attain higher levels of education had more desirable mathematics-related beliefs.

However, students’ perceptions of their parents’ expectations about mathematics achievement were not related to students’ mathematics-related beliefs in the same way as the more general parental educational expectations. Students who reported that their parents had no specific expectations possessed more desirable mathematics-related beliefs than all other subgroups. In addition, these students tended to perceive their mathematics achievement rank in their class to be higher on average than students who reported that their parents expressed some level of expectation for mathematics achievement.

Because this finding was not predicted, the researchers revised the original hypothesis. Their new prediction was that students who believe their parents have no specific mathematics achievement expectations possess more positive mathematics-related beliefs and higher perceived mathematics achievement than students who believe their parents do have specific expectations. They developed a revised rationale that drew on research on parental pressure and mathematics anxiety, positing that parents’ specific mathematics achievement expectations might increase their children’s sense of pressure and anxiety, thus fostering less positive mathematics-related beliefs. The team then conducted a follow-up study. Their findings aligned more closely with the new predictions and affirmed the better explanatory power of the revised rationale. The contributions of the study are found in this increased explanatory power—in the new understandings of this phenomenon contained in the revisions to the rationale.

Interpreting findings in order to revise hypotheses is not a straightforward task. Usually, the rationales blend multiple constructs or variables and predict multiple outcomes, with different outcomes connected to different research questions and addressed by different sets of data. Nevertheless, the contributions of your study depend on specifying the differences between your original hypotheses and your revised hypotheses. What can you explain now that you could not explain before?

We believe that revising hypotheses is an optimal response to any question of contributions because a researcher’s initial hypotheses plus the revisions suggested by the data are the most productive way to tie a study into the larger chain of research of which it is a part. Revised hypotheses represent growth in knowledge. Building on other researchers’ revised hypotheses and revising them further by more explicitly and precisely describing the conditions that are expected to influence the outcomes in the next study accumulates knowledge in a form that can be recorded, shared, built upon, and improved.

The significance of your study is presented in the opening sections of your evolving research paper whereas the contributions are presented in the final section, after the results. In fact, the central focus in this “Discussion” section should be a specification of the contributions (note, though, that this guidance may not fully align with the requirements of some journals).

Contributions Answer the Question of Generalizability

A common and often contentious, confusing issue that can befuddle novice and experienced researchers alike is the generalizability of results. All researchers prefer to believe the results they report apply to more than the sample of participants in their study. How important would a study be if the results applied only to, say, two fourth-grade classrooms in one school, or to the exact same tasks used as measures? How do you decide to which larger population (of students or tasks) your results could generalize? How can you state your claims so they are precisely those justified by the data?

To illustrate the challenge faced by researchers in answering these questions, we return to the JRME reviewers. We found that 30% of the reviews expressed concerns about the match between the results and the claims. For manuscripts that ultimately received a decision of Reject, the majority of reviewers said the authors had overreached—the claims were not supported by the data. In other words, authors generalized their claims beyond those that could be justified.

The Connection Between Contributions and Generalizability

In our view, claims about contributions can be examined productively alongside considerations of generalizability. To make the case for this view, we need to back up a bit. Recall that the purpose of research is to understand a phenomenon. To understand a phenomenon, you need to determine the conditions under which it occurs. Consequently, productive hypotheses specify the conditions under which the predictions hold and explain why and how these conditions make a difference. And the conditions set the parameters on generalizability. They identify when, where, and for whom the effect or situation will occur. So, hypotheses describe the extent of expected generalizability, and revised hypotheses that contain the contributions recalibrate generalizability and offer new predictions within these parameters.

An Example That Illustrates the Connection

In Chap. 4 , we introduced an example with a research question asking whether second graders improve their understanding of place value after a specially designed instructional intervention. We suggested asking a few second and third graders to complete your tasks to see if they generated the expected variation in performance. Suppose you completed this pilot study and now have satisfactory tasks. What conditions might influence the effect of the intervention? After careful study, you developed rationales that supported three conditions: the entry level of students’ understanding, the way in which the intervention is implemented, and the classroom norms that set expectations for students’ participation.

Suppose your original hypotheses predicted the desired effect of the intervention only if the students possessed an understanding of several concepts on which place value is built, only if the intervention was implemented with fidelity to the detailed instructional guidelines, and only if classroom norms encouraged students to participate in small-group work and whole-class discussions. Your claims of generalizability will apply to second-grade settings with these characteristics.

Now suppose you designed the study so the intervention occurred in five second-grade classrooms that agreed to participate. The pre-intervention assessment showed all students with the minimal level of entry understanding. The same well-trained teacher was employed to teach the intervention in all five classrooms, none of which included her own students. And you learned from prior observations and reports of the classroom teachers that three of the classrooms operated with the desired classroom norms, but two did not. Because of these conditions, your study is now designed to test one of your hypotheses—the desired effect will occur only if classroom norms encouraged students to participate in small-group work and whole-class discussions. This is the only condition that will vary; the other two (prior level of understanding and fidelity of implementation) are the same across classrooms so you will not learn how these affect the results.

Suppose the classrooms performed equally well on the post-intervention assessments. You expected lower performance in the two classrooms with less student participation, so you need to revise your hypotheses. The challenge is to explain the higher-than-expected performance of these students. Because you were interested in understanding the effects of this condition, you observed several lessons in all the classrooms during the intervention. You can now use this information to explain why the intervention worked equally well in classrooms with different norms.

Your revised hypothesis captures this part of your study’s contribution. You can now say more about the ways in which the intervention can help students improve their understanding of place value because you have different information about the role of classroom norms. This, in turn, allows you to specify more precisely the nature and extent of the generalizability of your findings. You now can generalize your findings to classrooms with different norms. However, because you did not learn more about the impact of students’ entry level understandings or of different kinds of implementation, the generalizability along these dimensions remains as limited as before.

This example is simplified. In many studies, the findings will be more complicated, and more conditions will likely be identified, some of which were anticipated and some of which emerged while conducting the study and analyzing the data. Nevertheless, the point is that generalizability should be tied to the conditions that are expected to affect the results. Further, unanticipated conditions almost always appear, so generalizations should be conservative and made with caution and humility. They are likely to change after testing the new predictions.

Contributions Are Assured When Hypotheses Are Significant and Methods Are Appropriate and Aligned

We have argued that the contributions of your study are produced by the revised hypotheses you can formulate based on your results. Will these revisions always represent contributions to the field? What if the revisions are minor? What if your results do not inform revisions to your hypotheses?

We will answer these questions briefly now and then develop them further in Part IV of this chapter. The answer to the primary question is “yes,” your revisions will always be a contribution to the field if (1) your hypotheses are significant and (2) you crafted appropriate methods to test the hypotheses. This is true even if your revisions are minor or if your data are not as informative as you expected. However, this is true only if you meet the two conditions in the earlier sentence. The first condition (significant hypotheses) can be satisfied by following the suggestions in the earlier section on significance. The second condition (appropriate methods) is addressed further in Part III in this chapter.

Implications

Before examining the role of methods in connecting significance with important contributions, we elaborate briefly our definition of “implications.” We reserve implications for the conclusions you can logically deduce from your findings that are not already presented as contributions. This means that, like contributions, implications are presented in the Discussion section of your research paper.

Many educational researchers present two types of implications: implications for future research and implications for practice. Although we are aware of this common usage, we believe our definition of “contributions” cover these implications. Clarifying why we call these “contributions” will explain why we largely reserve the word “implications” for recommendations regarding methods.

Implications for Future Research

Implications for future research often include (1) recommendations for empirical studies that would extend the findings of this study, (2) inferences about the usefulness of theoretical constructs, and (3) conclusions about the advisability of using particular kinds of methods. Given our earlier definitions, we prefer to label the first two types of implications as contributions.

Consider recommendations for empirical studies. After analyzing the data and presenting the results, we have suggested you compare the results with those predicted, revise the rationales for the original predictions to account for the results, and make new predictions based on the revised rationales. It is precisely these new predictions that can form the basis for recommending future research. Testing these new predictions is what would most productively extend this line of research. It can sometimes sound as if researchers are recommending future studies based on hunches about what research might yield useful findings. But researchers can do better than this. It would be more productive to base recommendations on a careful analysis of how the predictions of the original study could be sharpened and improved.

Now consider inferences about the usefulness of theoretical constructs. Our argument for labeling these inferences as contributions is similar. Rationales for predictions are where the relevant theoretical constructs are located. Revisions to these rationales based on the differences between the results and the predictions reveal the theoretical constructs that were affirmed to support accurate predictions and those that must be revised. In our view, usefulness is determined through this revision process.