Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Trauma informed interventions: A systematic review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations School of Nursing, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America, Bloomberg School of Public Health, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Nursing, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Nursing, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Nursing, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, United States of America

Affiliation Medstar Good Samaritan Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Hae-Ra Han,

- Hailey N. Miller,

- Manka Nkimbeng,

- Chakra Budhathoki,

- Tanya Mikhael,

- Emerald Rivers,

- Ja’Lynn Gray,

- Kristen Trimble,

- Sotera Chow,

- Patty Wilson

- Published: June 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747

- Reader Comments

Health inequities remain a public health concern. Chronic adversity such as discrimination or racism as trauma may perpetuate health inequities in marginalized populations. There is a growing body of the literature on trauma informed and culturally competent care as essential elements of promoting health equity, yet no prior review has systematically addressed trauma informed interventions. The purpose of this study was to appraise the types, setting, scope, and delivery of trauma informed interventions and associated outcomes.

We performed database searches— PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SCOPUS and PsycINFO—to identify quantitative studies published in English before June 2019. Thirty-two unique studies with one companion article met the eligibility criteria.

More than half of the 32 studies were randomized controlled trials (n = 19). Thirteen studies were conducted in the United States. Child abuse, domestic violence, or sexual assault were the most common types of trauma addressed (n = 16). While the interventions were largely focused on reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 23), depression (n = 16), or anxiety (n = 10), trauma informed interventions were mostly delivered in an outpatient setting (n = 20) by medical professionals (n = 21). Two most frequently used interventions were eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (n = 6) and cognitive behavioral therapy (n = 5). Intervention fidelity was addressed in 16 studies. Trauma informed interventions significantly reduced PTSD symptoms in 11 of 23 studies. Fifteen studies found improvements in three main psychological outcomes including PTSD symptoms (11 of 23), depression (9 of 16), and anxiety (5 of 10). Cognitive behavioral therapy consistently improved a wide range of outcomes including depression, anxiety, emotional dysregulation, interpersonal problems, and risky behaviors (n = 5).

Conclusions

There is inconsistent evidence to support trauma informed interventions as an effective approach for psychological outcomes. Future trauma informed intervention should be expanded in scope to address a wide range of trauma types such as racism and discrimination. Additionally, a wider range of trauma outcomes should be studied.

Citation: Han H-R, Miller HN, Nkimbeng M, Budhathoki C, Mikhael T, Rivers E, et al. (2021) Trauma informed interventions: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 16(6): e0252747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747

Editor: Vedat Sar, Koc University School of Medicine, TURKEY

Received: July 1, 2020; Accepted: May 23, 2021; Published: June 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Han et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: This is a systematic review. All relevant data were extracted from the published studies included in the review.

Funding: This study was supported, in part, by a grant from the Johns Hopkins Provost Discovery Award (HRH). Additional funding was received from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR003098, HRH), National Institute of Nursing Research (P30NR018093, HRH; T32NR012704, HM), National Institute on Aging (R01AG062649, HRH; F31AG057166, MN), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholar program (MN), and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (5T06SM060559‐ 07, PW). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. There was no additional external funding received for this study.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Despite the United States’ commitment to health equity, health inequities remain a pressing concern among some of the nation’s marginalized populations, such as racial/ethnic or gender minority populations. For example, according to the 2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 29.1% of Mexican Americans and 24.3% of African Americans with diabetes had hemoglobin A1C greater than 9% (the gold standard of glucose control with levels ≤ 7% deemed adequate), compared to 11% in non-Hispanic whites [ 1 ]. The 2016 survey also revealed that 40.9% and 41.5% of Mexican Americans and African Americans with hypertension, respectively, had their blood pressure under control, compared to 51.7% in non-Hispanic whites. In 2014, 83% of all new diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States occurred among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, with African American men having the highest rates [ 2 ].

Several factors have been discussed as root causes of health inequities. For example, Farmer et al. [ 3 ] noted structural violence—the disadvantage and suffering that stems from the creation and perpetuation of structures, policies and institutional practices that are innately unjust—as a major determinant of health inequities. According to Farmer et al., because systemic exclusion and disadvantage are built into everyday social patterns and institutional processes, structural violence creates the conditions which sustain the proliferation of health and social inequities. For example, a recent analysis [ 4 ] using a sample including 4,515 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants between 35 and 64 years of age revealed that black men and women had fewer years of education, were less likely to have health insurance, and had higher allostatic load (i.e., accumulation of physiological perturbations as a result of repeated or chronic stressors such as daily racial discrimination) compared to white men (2.5 vs 2.1, p <.01) and women (2.6 vs 1.9, p <.01). In the analysis, allostatic load burden was associated with higher cardiovascular and diabetes-related mortality among blacks, independent of socioeconomic status and health behaviors.

Browne et al. [ 5 ] identified essential elements of promoting health equity in marginalized populations such as trauma-informed and culturally competent care. In particular, trauma-informed care is increasingly getting closer attention and has been studied in a variety of contexts such as addiction treatment [ 6 – 8 ] and inpatient psychiatric care [ 9 ]. While there is a growing body of the literature on trauma-informed care, no prior review has systematically addressed trauma-informed interventions; one published review of literature [ 10 ] limited its scope to trauma survivors in physical healthcare settings. As such, the purpose of this paper is to conduct a systematic review and synthesize evidence on trauma-informed interventions.

For the purpose of this paper, we defined trauma as physical and psychological experiences that are distressing, emotionally painful, and stressful and can result from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances” such as a natural disaster, physical or sexual abuse, or chronic adversity (e.g., discrimination, racism, oppression, poverty) [ 11 , 12 ]. We aim to: 1) describe the types, setting, scope, and delivery of trauma informed interventions and 2) evaluate the study findings on outcomes in association with trauma informed interventions in order to identify gaps and areas for future research.

Five electronic databases—PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), SCOPUS and PsycINFO—were searched from the inception of the databases to identify relevant quantitative studies published in English. The initial literature search was conducted in January 2018 and updated in June 2019 using the same search strategy.

Review design

We conducted a systematic review of quantitative evidence to evaluate the effects of trauma informed interventions. Due to heterogeneity relative to study outcomes, designs, and statistical analyses approaches among the included studies, we qualitatively synthesized the study findings. Three trained research assistants extracted study data. Specifically, we used the PICO framework to extract and organize key study information. The PICO framework offers a structure to address the following questions for study evidence [ 13 ]: Patient problem or population (i.e., patient characteristics or condition); Intervention (type of intervention tested or implemented); Comparison or control (comparison treatment or control condition, if any), and Outcome (effects resulting from the intervention).

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria..

Articles were screened for their relevance to the purpose of the review. Articles were included in this review if the study was: about trauma informed approach (i.e., an approach to address the needs of people who have experienced trauma) or an aspect of this approach, published in English language and involved participants who were 18 years and older. Also, only quantitative studies conducted within a primary care or community setting were included.

Exclusion criteria.

Exclusion criteria were: studies in or with military populations, refugee or war-related trauma populations, studies with mental health experts and clinicians as research subjects or studies of incarcerated and inpatient populations. Conference abstracts that had limited information on study characteristics were also excluded.

Search strategy and selection of studies

Search strategy..

Following consultation with a health science librarian, peer-reviewed articles were searched in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SCOPUS and PsycINFO using MeSH and Boolean search techniques. Search terms included: "trauma focused" OR "trauma-focused" OR "trauma informed" OR "trauma-informed." We also searched for the term trauma within three words of informed or focus ((trauma W/3 informed) OR (trauma W/3 focused), or (traumaN3 (focused OR informed)). Detailed search terms for each database are provided in Appendix 1.

Study selection.

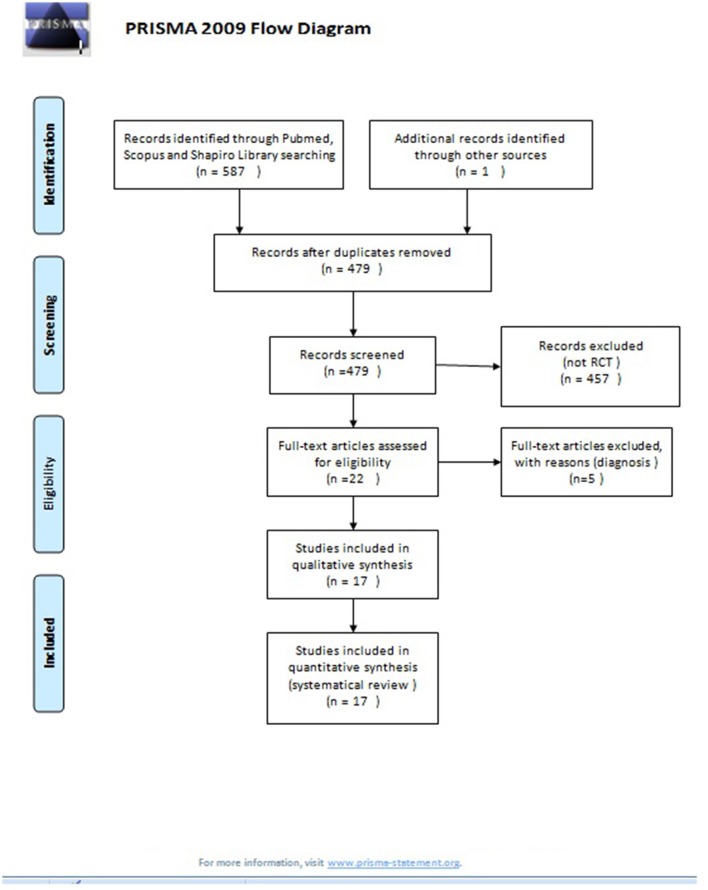

The initial electronic search yielded 7,760 references and the follow-up search yielded 5,207 which were all imported into the Covidence software for screening [ 14 ]. Screening of the references was conducted by 2 independent reviewers and disagreements were resolved through consensus. There were 4,103 duplicates removed from the imported articles and 8,864 studies were forwarded to the title and abstract screening stage. Eight thousand five hundred and twenty-one studies were excluded because they were irrelevant. Three hundred and forty-three abstracts were identified to be read fully. Following this, 311 articles were excluded for focusing on other psychological conditions (n = 120), were non-experimental studies (n = 78) and were in inpatient or incarcerated populations (n = 46). One additional companion article was identified during full text review. Therefore, thirty-three articles met the inclusion criteria and are reported in this review. Fig 1 provides details of the selection process and identifies the reasons why articles were excluded at each stage.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.g001

Quality assessment

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute quality appraisal tools [ 15 ] for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, and retrospective studies to assess the rigor of each study included in this review. The Joanna Briggs Institute quality appraisal tools [ 15 ] include items asking about methodological elements that are critical to the rigor of each type of study designs. In particular, one of the items for RCTs addresses participant blinding to treatment assignment. Due to the nature of trauma-informed interventions included in our review, it was decided that participant blinding is not relevant and hence was removed from the appraisal list for RCTs. No studies were excluded on the basis of the quality assessment. The quality assessment process was conducted independently by two raters. Inter-rater agreement rates ranged from 56% to 100% with the resulting statistic indicating substantial agreement (average inter-rater agreement rate = 77%). Discrepancies between raters were resolved via inter-rater discussion.

Overview of studies

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the 32 unique studies included in the review, with one companion article [ 16 ] for a study which was later reported with a more thorough examination of findings [ 17 ] totaling 33 articles. More than half (n = 19) of the 32 studies were RCTs [ 17 – 35 ] whereas twelve studies were quasi-experimental [ 36 – 47 ] and one was retrospective study [ 48 ]. Thirteen studies were conducted in the U.S. [ 17 – 19 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 35 , 39 – 41 , 45 , 47 ]; five in the Netherlands [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 38 , 48 ]; three in Canada [ 23 , 25 , 46 ]; two in Australia [ 21 , 24 ]; two in the United Kingdom [ 36 , 44 ]; two in Sweden [ 42 , 43 ]; on study in Chile [ 20 ]; Iran [ 32 ]; Haiti [ 37 ]; South Africa [ 34 ]; and Germany [ 28 ]. Fourteen of the studies only included females in their sample [ 18 , 20 , 21 , 23 – 25 , 27 , 28 , 38 – 41 , 45 , 48 ]. The average sample size was 78 participants, with a range from 10 participants [ 38 ] to 297 participants [ 48 ]. Of the studies included, 67% had a sample size above 50 [ 18 – 22 , 26 , 29 – 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 – 42 , 46 – 48 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t001

The studies included in this review recruited their study populations largely based on the type of trauma they were aiming to address, such as individuals that experienced interpersonal traumatic event such as child abuse, sexual assault, or domestic violence [ 16 – 18 , 20 – 22 , 24 – 26 , 35 , 40 – 43 , 45 , 46 ], individuals with substance abuse disorders [ 19 , 47 , 48 ], couples experiencing clinically significant marital issues [ 23 ], individuals with limb amputations [ 38 ], dental phobia [ 28 ], or fire service personnel suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder [ 44 ]. Trauma was self-reported in eight articles [ 16 , 17 , 20 , 22 , 26 , 34 , 35 , 47 ]. In contrast, nine studies clearly identified a measurement of trauma; the Trauma History Questionnaire [ 19 , 45 ], the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [ 23 , 25 ], the Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule [ 23 ], the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale adapted for sex work [ 39 ], the Traumatic Events Screening Instrument for Adults [ 27 ], the Life Events Checklist [ 46 ], and the Adverse Childhood Experiences [ 18 ]. Two studies used a clinical tool (e.g. eye movement desensitization and reprocessing [ 38 ] and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4 th edition [ 41 ] to identify or diagnose trauma. Fifteen studies did not include direct measurements for trauma [ 21 , 24 , 28 – 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 42 – 44 , 48 ].

Quality ratings

Tables 2 – 4 shows final scores of quality assessment. Quality of the 32 unique studies included in this review varied across individual studies. Twelve of 19 RCTs included in the review were of high quality (i.e., 9 to 11) [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 – 35 ] and six were of medium quality (i.e., 5 to 8) [ 19 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 27 , 30 ]. One study scored 4 of 12 [ 32 ]. The low rating study [ 32 ] lacked relevant information to adequately score its methodological rigor. Most RCTs clearly described randomization, group equivalence at baseline, rates and reasons for attrition, study outcomes, and analysis. Blinding of outcomes assessors to treatment assignment was used and described in several RCTs [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 27 , 35 ], whereas blinding of those delivering treatment was discussed clearly in only one study [ 25 ]. The majority of the quasi-experimental studies were of high quality (i.e., 7 or higher), except two, which scored 2 of 9 [ 37 ] and 6 of 9 [ 39 ], respectively. Six of twelve quasi-experimental studies [ 36 , 41 – 44 , 47 ] had a comparison group to strengthen internal validity of causal inferences by comparing intervention and control groups. Some of these studies, however, noted differences in baseline assessments between groups [ 36 , 43 , 44 ]. Finally, one retrospective study [ 48 ] scored 11 of 11 and hence was rated as high quality.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t004

Characteristics of trauma-informed interventions

Type of intervention..

Table 5 details the trauma informed intervention characteristics included in this review. The two most frequently used interventions were eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) [ 28 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 38 ]—a multi-phase intervention using bilateral stimulation, such as left-to-right eyes movements or hand tapping, to desensitize individuals to a traumatic memory or image—and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [ 26 , 27 , 32 , 46 , 48 ]—a psychological approach to introduce emotional regulation and coping strategies (e.g., deep muscle relaxation, yoga, thought discovery and breathing techniques) to deal with negative feelings and behaviors surrounding a trauma of interest [ 32 , 48 ]. The implementation of CBT varied on the trauma of interest. Other studies implemented interventions using general trauma focused therapy [ 22 , 43 ], emotion focused therapy [ 23 , 25 ], stress reduction programs [ 17 ], cognitive processing therapy [ 24 ], brief electric psychotherapy [ 31 ], present focused group therapy [ 26 ], compassion focused therapy [ 44 ], prolonged exposure [ 45 ], stress inoculation training [ 45 ], psychodynamic therapy [ 45 ], and visual schema displacement therapy [ 30 ]. A number of studies included more than one of these therapies [ 13 , 26 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 45 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.t005

Setting, scope, and delivery of intervention.

Twenty of the interventions were identified to occur in an outpatient clinic/setting [ 19 – 21 , 24 , 25 , 27 – 29 , 31 – 34 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 43 , 46 – 48 ]. Four of the studies took place in a research lab or office [ 23 , 26 , 41 , 45 ], one study occurred in the community [ 17 ], and one study implemented therapy in three locations, two of which were outpatient and one of which was a residential treatment center [ 47 ]. Lastly, one study occurred in internally displaced people’s camps within a metropolitan area in Haiti [ 37 ]. The remaining studies did not identify a specific setting [ 22 , 35 , 38 , 44 ].

The interventions ranged in length and time, but most often occurred weekly. The longest intervention was done by Lundqvist and colleagues [ 43 ], which lasted a total length of 2-years and included 46 sessions. Several other studies included 20 sessions or more [ 18 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 ]. The interventions were most commonly delivered by medical professionals, including but not limited to: psychologists or psychiatrists, therapists, social workers, mental health clinicians and physicians [ 16 , 17 , 20 – 29 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 44 – 47 ]. The articles frequently noted that the interventionists were masters-level-prepared or higher in their profession [ 21 , 23 , 25 – 27 , 33 , 40 , 47 ]. In addition to standard education and licensure, many of the professionals implementing the interventions were required to obtain further training in the therapy of interest [ 23 – 25 , 27 – 30 , 33 , 36 , 38 – 40 , 46 , 47 ]. Two studies were identified to be delivered by lay persons [ 34 , 37 ].

Fidelity was addressed in 16 of the included articles [ 16 , 19 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 26 – 30 , 33 – 35 , 45 – 47 ]. The manner in which fidelity was addressed varied by study. Videotaping or audiotaping therapy sessions [ 21 , 23 , 24 , 28 – 30 , 33 , 35 ] were most common, followed by deploying regular supervision of the therapy sessions [ 21 , 23 , 27 , 29 , 33 , 46 ], using a training manual or intervention protocols [ 19 , 21 , 33 , 46 ], or having individuals unaffiliated with the study or blind to the intervention rate sessions [ 21 , 26 , 28 , 35 ]. Additionally, three articles utilized fidelity checks/checklists to ensure components of the intervention were addressed [ 16 , 30 , 47 ] or had patients and/or therapists rate therapy sessions [ 26 , 34 , 45 ]. Finally, one study had quality assurance worksheets completed after each session that were later reviewed by the study coordinator [ 34 ].

Effects of trauma-informed interventions

Trauma-informed interventions were tested to improve several psychological outcomes, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. The most frequently assessed psychological outcome was PTSD, which was examined in 23 out of the 32 studies [ 17 , 20 – 27 , 31 , 33 , 35 – 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 – 48 ]. Among the studies that assessed PTSD as an outcome, 11 found significant reductions in PTSD symptoms and severity following the trauma-informed intervention [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 34 , 42 , 45 – 47 ], however, one of these studies, which utilized outpatient psychoeducation, did not find significant differences in reduction between the intervention and control group [ 20 ]. Trauma-informed interventions that were associated with a significant reduction in PTSD were a mindfulness-based stress reduction program [ 16 ], two therapies using the Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) [ 47 ], CBT [ 26 , 46 ], EMDR [ 28 ], general trauma-focused therapy [ 42 ], psychodynamic therapy [ 45 ], stress inoculation therapy [ 45 ], present-focused therapy [ 26 ], and cognitive processing therapy [ 24 ]. In addition, an intervention designed to reduce stress and improve HIV care engagement improved PTSD symptoms; however, this intervention was not intended to treat PTSD [ 34 ].

Other commonly assessed psychological symptoms, including depression and anxiety, were examined in 16 [ 17 – 21 , 24 – 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 40 , 44 , 47 , 48 ] and 10 [ 21 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 44 , 47 , 48 ] studies, respectively. Among these, trauma-informed interventions were associated with decreased or improved depressive symptoms in 9 studies [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 32 , 35 , 47 , 48 ] and decreased or improved anxiety in 5 studies [ 21 , 28 , 35 , 47 , 48 ]. For example, Vitriol and colleagues found that outpatient psychoeducation resulted in improved depressive symptoms in women with severe depression and childhood trauma [ 20 ]. Similarly, Kelly and colleagues found that female survivors of interpersonal violence experienced a significantly greater reduction of depressive symptoms in the intervention group (mindfulness-based stress reduction) compared to the control group [ 16 , 17 ]. Other therapies that resulted in improved depressive symptoms were TREM [ 47 ], prolonged exposure therapy [ 21 ], CBT [ 32 , 46 ], psychoeducational cognitive restructuring [ 35 ], and financial empowerment education [ 18 ]. Cognitive processing therapy similarly resulted in large reductions in depression symptoms, however this reduction was also observed in the control group [ 24 ]. The same studies showed that TREM [ 47 ], prolonged exposure therapy [ 21 ], CBT [ 48 ], and psychoeducational cognitive restructuring [ 35 ] were associated with improved anxiety. Lastly, in a separate study than the one highlighted above, EMDR was associated with improved anxiety [ 28 ].

A select number of the studies found associations between trauma-informed interventions and other psychological outcomes such as attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, psychiatric symptoms or dental distress. For example, the trauma-informed mindfulness-based reduction program implemented by Kelly and colleagues was associated with a greater decrease in anxious attachment, measured by the Relationship Structures Questionnaire, compared to the waitlist group [ 17 ]. Similarly, Masin-Moyer and colleagues found that TREM and an attachment-informed TREM (ATREM) were associated with significant reductions in group attachment anxiety, group attachment avoidance, and psychological distress in women with a history of interpersonal trauma [ 47 ]. Additionally, individuals in an outpatient substance abuse treatment program, consisting of psychoeducational seminars and trauma-informed addiction treatment, experienced significantly better outcomes of psychiatric severity, measured by the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs scale, compared to a control treatment group [ 19 ]. Doering and colleagues found that EMDR, compared to the control group, was associated with significantly greater improvement in dental stress, anxiety and fear in patients with dental-phobia [ 28 ].

There was a series of interpersonal, emotional and behavioral outcomes assessed in the included studies. For example, adult females that were sexually abused in childhood experienced a significant improvement in social interaction and social adjustment after receiving trauma focused group therapy [ 43 ]. Similarly, Dalton and colleagues found that couples that received emotion focused therapy experienced a significant reduction in relationship distress [ 23 ] and MacIntosh and colleagues found that individuals that received CBT reported lower interpersonal problems post-treatment [ 46 ]. Trauma-based interventions were also associated with emotional outcomes. Visual schema displacement therapy and EMDR both were superior to the control treatment in reducing emotional disturbance and vividness of negative memories [ 30 ]. In a separate study, CBT was found to reduce levels of emotional dysregulation in individuals that experienced childhood sexual abuse [ 46 ]. Lastly, trauma-informed interventions were associated with behavioral outcomes, including HIV risk reduction [ 26 ], decreased days of alcohol use [ 27 ], and improvements in avoidance of client condom negotiations, frequency of sex trade under influence of drugs or alcohol, and use of intimate partner violence support [ 40 ]. Interventions that were associated with these behavioral outcomes included trauma focused and present focused group therapy [ 26 ], CBT [ 27 ], and a trauma-informed support, validation, and safety-promotion dialogue intervention [ 40 ].

Publication bias

We analyzed three sets of outcome variables for publication bias: PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Based on Begg and Mazumdar test, there was no evidence of publication bias for PTSD (z = 1.55, p = 0.121) and anxiety (z = 0.29, p = 0.769). However, there was some evidence of publication bias for depression (z = 5.19, p<.001). The statistically significant publication bias for depression appears to be mainly due to large effect sizes in Nixon [ 24 ] and Bowland [ 35 ].

According to our database search, this is the first systematic review to critically appraise trauma-informed interventions using a comprehensive definition of trauma. In particular, our definition encompassed both physical and psychological experiences resulting from various circumstances including chronic adversity. Overall, there was inconsistent evidence to suggest trauma informed interventions in addressing psychological outcomes. We found that trauma-informed interventions were effective in improving PTSD [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 34 , 42 , 45 – 47 ] and anxiety [ 21 , 28 , 35 , 47 , 48 ] in less than half of the studies where these outcomes were included. We also found that depression was improved in less than about two thirds of the studies where the outcome was included [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 32 , 35 , 47 , 48 ]. Although limited in the number of published studies included this review, available evidence consistently supported trauma-informed interventions in addressing interpersonal [ 23 , 43 , 46 ], emotional [ 30 , 46 ], and behavioral outcomes [ 26 , 27 , 40 ].

Effective trauma informed intervention models used in the studies varied, encompassing CBT, EMDR, or other cognitively oriented approaches such as mindfulness exercises [ 16 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 32 , 35 , 45 , 46 , 48 ]. In particular, CBT was noted as an effective trauma informed intervention strategy which successfully led to improvements in a wide range of outcomes such as depression [ 32 , 48 ], anxiety [ 48 ], emotional dysregulation [ 46 ], interpersonal problems [ 23 , 46 ], and risky behaviors (e.g., days of alcohol use) [ 27 ]. While the majority of the studies included in the review were focused on interpersonal trauma such as child abuse, sexual assault, or domestic violence [ 16 – 18 , 20 – 22 , 24 – 26 , 35 , 40 – 43 , 45 , 46 ], growing evidence demonstrates perceived discrimination and racism as significant psychological trauma and as underlying factors in inflammatory-based chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes [ 4 ]. Future trauma informed interventions should consider a wide-spectrum of trauma types, such as racism and discrimination, by which racial/ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected from [ 49 ].

While the majority of the trauma informed interventions were delivered by specialized medical professionals trained in the therapy [ 16 , 17 , 20 – 29 , 33 , 36 , 38 – 41 , 44 – 47 ], several of the articles lacked full descriptions of interventionist training and fidelity monitoring [ 20 , 22 , 25 , 36 , 38 – 41 , 44 ]. Two studies were identified to be delivered by lay persons [ 34 , 37 ]. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that lay persons, upon training, can successfully cover a wide scope of work and produce the full impact of community-based intervention approaches [ 50 ]. Given such, there is a strong need for trauma informed intervention studies to clearly elaborate the contents and processes of lay person training such as competency evaluation and supervision to optimize the use of this approach.

There are methodological issues to be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings in this review. While twenty-three of 32 studies were of high quality [ 17 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 33 – 36 , 38 , 40 – 48 ], some studies lacked methodological rigor, which might have led to false negative results (no effects of trauma informed interventions). For example, about one-third (31%) had a sample size less than 50 [ 17 , 23 – 25 , 27 , 28 , 35 , 38 , 43 , 45 ]. In addition, half of the quasi-experimental studies [ 37 – 40 , 45 , 46 ] did not have a comparison group or when they had one, group differences were noted in baseline assessments [ 36 , 43 , 44 ]. In several studies, therapists took on both traditional treatment and research responsibilities (e.g., delivery of the intervention) [ 20 , 25 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 40 , 46 , 47 ], yet blinding of those delivering treatment was discussed clearly in only one study [ 25 ]. This dual role is likely to have led to the disclosure of group allocation, hence, threatening the internal validity of the results. Future studies should address these issues by calculating proper sample size a priori, using a comparison group, and concealing group assignments.

Review limitations

Several limitations of this review should be noted. First, by using narrowly defined search terms, it is possible that we did not extract all relevant articles in the existing literature. However, to avoid this, we conducted a systematic electronic search using a comprehensive list of MeSH terms, as well as similar keywords, with consultation from an experienced health science librarian. Additionally, we hand searched our reference collections, Second, the trauma informed interventions included in this review were implemented to predominantly address trauma related to sexual or physical abuse among women. Thus, our findings may not be applicable to trauma related to other types of incidence such as chronic adversity (e.g., racism or discrimination). Likewise, there were insufficient studies addressing a wider range of trauma impacts such as emotion regulation, dissociation, revictimization, non-suicidal self-injury or suicidal attempts, or post-traumatic growth. Future research is warranted to address these broader impacts of trauma. We included only articles written in English; therefore, we limited the generalizability of the findings concerning studies published in non-English languages. Finally, we used arbitrary cutoff scores to categorize studies as low, medium, and high quality (quality ratings of 0-4, 5-8, and 9+ for RCTs and 0-3, 4-6, 7+ for quasi-experimental studies, respectively). Using this approach, each quality-rating item was equally weighted. However, certain factors (e.g., randomization method) may contribute to the study quality more so than others.

Our review of 33 articles shows that there is inconsistent evidence to support trauma informed interventions as an effective intervention approach for psychological outcomes (e.g., PTSD, depression, and anxiety). With growing evidence in health disparities, adopting trauma informed approaches is a growing trend. Our findings suggest the need for more rigorous and continued evaluations of the trauma informed intervention approach and for a wide range of trauma types and populations.

Supporting information

S1 checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.s001

S1 Appendix. Search strategies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252747.s002

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to a medical librarian, Stella Seal for her assistance with article search. Both Kristen Trimble and Sotera Chow were students in the Masters Entry into Nursing program and Hailey Miller and Manka Nkimbeng were pre-doctoral fellows at The Johns Hopkins University when this work was initiated.

- 1. Health disparities data. 2020 May 28 [cited 28 May 2020]. In healthypeople.gov [Internet]. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/health-disparities-data/health-disparities-widget .

- 2. HIV and AIDS. 2018 April [cited 28 May, 2020]. In: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/effectivetreatment/hiv.html .

- 3. Farmer P, Kim YJ, Kleinman A, Basilico M. Introduction: A biosocial approach to global health. In: Farmer P, Kim YJ, Kleinman A, Basilico M, editor. Reimagining global health: An introduction. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2013. p. 1–14.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 11. National Institute of Mental Health. Helping children and adolescents cope with violence and disasters: What parents can do. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

- 12. Trauma and violence. 2019 [Last updated on August 2]. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/trauma-violence .

- 13. Evidence-based practice in health. 2020 Dec 21. [cited 21 December 2020]. [Internet]. Available from https://canberra.libguides.com/c.php?g=599346&p=4149722#s-lg-box-12888072 .

- 14. Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation. 2019 [Last updated on February 4]. [Internet]. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/ .

- 15. Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E MZ, editor. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual . The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

EMDR beyond PTSD: A Systematic Literature Review

Alicia valiente-gómez, ana moreno-alcázar, carlos cedrón, francesc colom, víctor pérez, benedikt l amann.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Nuno Conceicao, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal

Reviewed by: Udi Oren, EMDR Institute of Israel, Israel; Nam Hee Kim, National Center for Mental Health, South Korea

*Correspondence: Ana Moreno-Alcázar [email protected]

This article was submitted to Clinical and Health Psychology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Received 2017 Jun 29; Accepted 2017 Sep 11; Collection date 2017.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Background: Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a psychotherapeutic approach that has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) through several randomized controlled trials (RCT). Solid evidence shows that traumatic events can contribute to the onset of severe mental disorders and can worsen their prognosis. The aim of this systematic review is to summarize the most important findings from RCT conducted in the treatment of comorbid traumatic events in psychosis, bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and chronic back pain.

Methods: Using PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Scopus, we conducted a systematic literature search of RCT studies published up to December 2016 that used EMDR therapy in the mentioned psychiatric conditions.

Results: RCT are still scarce in these comorbid conditions but the available evidence suggests that EMDR therapy improves trauma-associated symptoms and has a minor effect on the primary disorders by reaching partial symptomatic improvement.

Conclusions: EMDR therapy could be a useful psychotherapy to treat trauma-associated symptoms in patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Preliminary evidence also suggests that EMDR therapy might be useful to improve psychotic or affective symptoms and could be an add-on treatment in chronic pain conditions.

Keywords: eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, PTSD, psychosis, bipolar disorder, chronic pain, unipolar depression, RCT

Introduction

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a psychotherapeutic approach developed in the late 80s by Francine Shapiro (Shapiro, 1989 ) that aims to treat traumatic memories and their associated stress symptoms. This therapy consists of a standard protocol which includes eight phases and bilateral stimulation (usually horizontal saccadic eye movements) to desensitize the discomfort caused by traumatic memories and the aim of the therapy is to achieve their reprocessing and integration within the patient's standard biographical memories (Shapiro, 2005 ). The effectiveness of EMDR therapy in treating Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) has undergone the scrutiny of several meta-analyses (Van Etten and Taylor, 1998 ; Bradley et al., 2005 ; Davidson and Parker, 2005 ; Seidler and Wagner, 2006 ; Benish et al., 2008 ; Jonas et al., 2013 ; Chen et al., 2014 , 2015 ); this led to the final recognition by the World Health Organization (2013) as a psychotherapy of choice in the treatment of PTSD in children, teenagers, and adults 1 . Moreover, the application of EMDR therapy is not restricted to the treatment of people with PTSD and its use is currently expanding to the treatment of other conditions and comorbid disorders to PTSD (de Bont et al., 2013 ; Novo et al., 2014 ; Perez-Dandieu and Tapia, 2014 ). In this context, it is important to note that traumatic events belong to the etiological underpinnings of many psychiatric disorders (Kim and Lee, 2016 ; Millan et al., 2017 ). In addition, a comorbid diagnosis of PTSD can worsen the prognosis of other psychiatric disorders (Assion et al., 2009 ). Therefore, investigation in EMDR therapy has increased beyond PTSD and several studies have analyzed the effect of this therapy in other mental health conditions such as psychosis, bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and chronic back pain. The aim of this systematic and critical review is to summarize the most important results of the available randomized controlled trials (RCT) conducted in this field.

Using PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Scopus, we conducted a systematic literature search of studies published up to December 2016, which examined the use of EMDR therapy in other psychiatric disorders beyond PTSD. The search terms were selected from the thesaurus of the National Library of Medicine (Medical Subject Heading Terms, MeSH) and the American Psychological Association (Psychological Index Terms) and included the terms “EMDR,” “schizophrenia,” “psychotic disorder,” “bipolar disorder,” “depression,” “anxiety disorder,” “alcohol dependence,” “addiction,” and “chronic pain.” The final search equation was defined using the Boolean connectors “AND” and “OR” following the formulation “EMDR” AND “schizophrenia”, “psychotic disorder,” “bipolar disorder,” “depression,” “anxiety disorder,” “alcohol or substance dependence” OR “addiction,” “chronic pain.” The automatic search was completed with a manual snowball search using reference lists of included papers and web-based searches in an EMDR-centered library ( https://emdria.omeka.net/ ). The search included English-published articles from 01/01/1997 to 31/12/2016 and did not include any subheadings or tags (i.e., search fields “All fields”). Furthermore, we performed a manual search of the references list of previous meta-analysis and the retrieved articles. Case reports, serial cases, unpublished studies, and non-randomized studies, were excluded from this systematic review. Due to the significant heterogeneity of the studies, a formal quantitative synthesis (i.e., meta-analysis) was not possible. Instead, a systematic review was conducted using the PRISMA guidelines as referenced above. Prisma 2009 checklist (Supplementary Datasheet ) and flow chart (Figure 1 ), as well as the Jadad scale (Supplementary Table ) for reporting RCT have been completed and included in the Supplementary Material.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram. From Moher et al. ( 2009 ).

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

The final selection of the articles was carried out using the following criteria: (i) RCT published in peer-reviewed journals, (ii) in adult populations (over 18 years) that (iii) examined the use of EMDR therapy in different psychiatric disorders (as previously described). The criteria for exclusion were: (i) articles that did not contain original research (i.e., reviews and meta-analyses and (ii) quasi-experimental designs (single case and/or no control group). The studies were selected by Alicia Valiente-Gómez and discrepancies were resolved by Ana Moreno-Álcazar and Benedikt L. Amann.

EMDR therapy in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders

Since 2010, five datasets of RCT have been published in patients with a psychotic disorder and a comorbid PTSD or traumatic events (see Table 1 ) (Kim et al., 2010 ; de Bont et al., 2013 , 2016 ; van den Berg et al., 2015 ; Van Minnen et al., 2016 ). These consist of two pilot studies (Kim et al., 2010 ; de Bont et al., 2013 ) and one large RCT (van den Berg et al., 2015 ) with two further subanalysis (de Bont et al., 2016 ; Van Minnen et al., 2016 ).

RCT of EMDR in psychotic disorder.

RCT, Randomized controlled trial; EMDR, Eye Movement desensitization and reprocessing; PR, progressive relaxation; TAU, treatment as usual; PE, Prolonged exposure; WL, wait-list control; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; DS, Dissociative Subtype of PTSD; NDS, Non-Dissociative Subtype of PTSD.

These data sets corresponds to the clinical trial ISRCTN 79584912 of van den Berg et al. ( 2015 ) .

A Korean group (Kim et al., 2010 ) carried out the first RCT including 45 acute schizophrenic inpatients. Patients were randomized to 3 weekly sessions of EMDR therapy (lasting 60 to 90 min) ( n = 15), 3 weekly sessions of progressive muscle relaxation therapy ( n = 15) (the first session lasted 90 min and the other two sessions lasted 60 min), and treatment as usual (TAU, n = 15). In the EMDR condition, the therapeutic treatment targets included stressful life events related with the current admission, traumatic incidents from childhood or adulthood, treatment-related adverse events (e.g., involuntary admission or seclusion), and the experience of distressing psychotic symptoms. All patients received TAU, which consisted of naturalistic psychopharmacological treatment, individual supportive psychotherapy, and group activities whilst being admitted. All groups showed an improvement of the symptomatic domains, which included psychotic, anxious, and depressive symptoms, measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A). The variance analysis (ANOVA), revealed a significant improvement over time in each of the treatment groups; however, there was no significant differences between treatment groups for the total PANSS ( F = 0.73, p = 0.49), HAM-D ( F = 0.41, p = 0.67), or HAM-A ( F = 0.70, p = 0.51). Still, the effect size for negative symptoms was larger for the EMDR condition (0.60 for EMDR, 0.39 for PMR and 0.21 for TAU only, no significant differences).

A Dutch group published a small pilot RCT in patients with psychosis and PTSD in 2013 (de Bont et al., 2013 ). Patients were randomized to prolonged exposure (PE) ( n = 5) or EMDR therapy ( n = 5) to treat PTSD symptoms with a maximum of 12 weekly sessions of 90 min. The PTSD diagnosis was verified using the Clinical-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) and the Post-traumatic Stress Symptom Scale Self-Report (PSS-SR). All patients were assessed with the Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scale interview (PSYRATS) and the Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale (GPTS) for psychotic symptoms. The mixed-model showed that in the intention to treat analysis, both groups reached a significant decrease of PTSD symptoms during the treatment phase ( p < 0.001, r = 0.64), this effect was maintained in the post-treatment phase ( p < 0.001, r = 0.73) and in the 3 months follow up phase ( p < 0.001). The same group conducted a large single-blind RCT including a sample of 155 outpatients with a psychotic disorder (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder) and a comorbid PTSD (van den Berg et al., 2015 ). Patients were randomized to three different groups (PE, EMDR, and Waiting-List Condition). Forty-seven patients were in the waiting-list condition (WL), for the other two conditions, PE ( N = 53) and EMDR therapy ( N = 55), patients received 8 weekly sessions of 90 min each. PTSD symptoms were evaluated with the CAPS, PSS-SR, and the Post-traumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI). The authors found that EMDR and PE therapy were both superior to the WL condition in reducing PTSD symptoms (PE effect size 0.78, t = −3.84, p = 0.001; EMDR effect size 0.65, t = −3.26, p = 0.001). No significant differences were detected between PE and EMDR therapy.

Two further subanalysis of the main study were published (de Bont et al., 2016 ; Van Minnen et al., 2016 ). The first subanalysis (de Bont et al., 2016 ) provided evidence, that the severity of paranoid thoughts assessed by GPTS, decreased in a significant way (PE t = −2.86, p = 0.005; EMDR t = −2.68, p = 0.008) and rates of remission for psychotic disorders increased for both treatment conditions in comparison to the WL arm (de Bont et al., 2016 ). In another secondary analysis with a subsample of 108 patients (Van Minnen et al., 2016 ), the authors evaluated the effectiveness of both trauma-focused treatment for patients with psychosis with and without the dissociative subtype of PTSD. This diagnosis was established regarding the items 29 (derealization) and/or 30 (depersonalization) (frequency ≥1 and intensity ≥2) on the CAPS. They though that, even though patients with a dissociative subtype of PTSD, showed significantly more severe PTSD symptoms at pre-treatment ( t = −0.29, p = 0.005), the CAPS scores did no longer differ at post-treatment ( t = −1.34, p = 1.85), when compared to patients without the dissociative subtype of PTSD.

In summary, one pilot study (Kim et al., 2010 ) found that EMDR therapy did not have a superior effect over progressive relaxation therapy or TAU in reducing trauma symptoms patients with PTSD and a psychotic disorder. In contrast, another preliminary study provided a comparable effect of EMDR therapy to PE (de Bont et al., 2013 ). This was confirmed by a large and well-designed study (van den Berg et al., 2015 ) that suggested that patients with a psychotic disorder and PTSD improved both with EMDR therapy and PE therapy (comparable to WL) in trauma-associated and paranoid symptoms, despite the impact and the high prevalence of comorbid PTSD in psychotic disorders, evidence of the use of EMDR therapy in psychosis and trauma is still scarce.

EMDR therapy in affective disorders

Emdr therapy in bipolar disorder.

So far, only 1 RCT has investigated the efficacy of EMDR therapy in bipolar disorder (Novo et al., 2014 ). Twenty bipolar patients with subsyndromal symptoms and a history of traumatic events were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of treatment with EMDR therapy or TAU. The participants were re-assessed at the end of this period and after a further 12 weeks of follow-up. Results showed significant reductions in affective scores in favor of the EMDR group after treatment. Affective symptoms were assessed through the HAM-D ( F = 23.86, p = 0.001) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) ( F = 14.41, p = 0.004). However, changes from baseline to 24 weeks follow-up did not reach statistical significance. Regarding trauma symptoms, assessed by the CAPS and the Impact Event Scale (IES), results showed significant improvement in the EMDR group after treatment in both measures (CAPS F = 6.26, p = 0.03; IES F = 20.36, p = 0.001). At the follow-up assessment, only the IES scores remained statistically significant ( F = 20.32, p = 0.003). Functional impairment was also assessed, but no group differences were found (Table 2 ).

RCTs of EMDR in affective disorder, substance use disorders and chronic pain.

RCT, Randomized controlled trial; EMDR, Eye Movement desensitization and reprocessing; TAU, Treatment as usual; WL, waiting list .

EMDR therapy in unipolar depression

Two controlled studies in EMDR therapy have been performed in unipolar depressive disorders (Behnammoghadam et al., 2015 ; Hase et al., 2015 ). A matched pairs study (Hase et al., 2015 ) was conducted with 32 inpatients currently suffering from mild-to-moderate depressive episodes related to recurrent depression according to the ICD-10 criteria. One group was treated with EMDR therapy ( N = 16) in addition to TAU and matched by time of admission, gender and age with 16 controls who only received TAU. Usually, only one EMDR session was provided. In the case of an incomplete session, a second EMDR therapy session was added. EMDR therapy focused on disturbing memories related to the onset and course of the depressive disorder; however, most of the traumatic memories did not meet PTSD criteria. The TAU arm consisted of individual psychodynamic psychotherapy, group therapy sessions and five group sessions of psychoeducation. All patients were assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist 90 revised (SCL-90-R), and the SCL-90-R Global Severity Index (GSI). The authors found that TAU plus EMDR therapy was more effective than TAU by itself in reducing depressive symptoms [significant pre-post differences in SCL-90-R GSI score ( p = 0.015) and in SCL-90-R Depression subscale score ( p = 0.04)].

Regarding the second study, the efficacy of EMDR therapy on depression of patients with post-myocardial infarction was tested (Behnammoghadam et al., 2015 ). Sixty patients were randomized to EMDR therapy, receiving three sessions of 45–90 min per week during 4 months, or to a control group without any psychotherapeutic intervention. All participants were assessed by the BDI at the beginning and end of the study. The EMDR group showed significant differences in the depressive scores of the BDI before and after the EMDR therapy (27.26 ± 6.41 and 11.76 ± 3.71, p < 0.001). Mean scores of BDI also resulted significantly different between both groups at the end of the study (experimental group 11.76 ± 3.71 vs. control group 31.66 ± 6.09, p < 0.001). The authors concluded that EMDR therapy was an effective, useful, efficient and non-invasive method to treat depressive disorders in post-myocardial infarction patients (Table 2 ).

In summary, EMDR therapy has demonstrated preliminary positive evidence in one RCT as a promising therapy to treat depressive symptoms in unipolar depression (Hase et al., 2015 ). Furthermore, it might be a helpful tool to facilitate psychological and somatic improvement in patients with myocardial infarction who suffer subsequent depressive symptoms (Behnammoghadam et al., 2015 ).

EMDR therapy in anxiety disorders

Six randomized studies have been carried out with EMDR therapy in anxiety disorders, beyond the diagnosis of PTSD (see Table 3 ) (Feske and Goldsteina, 1997 ; Goldstein et al., 2000 ; Nazari et al., 2011 ; Doering et al., 2013 ; Triscari et al., 2015 ; Staring et al., 2016 ).

RCTs of EMDR in anxiety disorders.

RCT, Randomized controlled trial; EMDR, Eye Movement desensitization and reprocessing; WL, wait-list control; EFER, Eye fixation exposure and reprocessing; TAU, treatment as usual; CPT, Citalopram; BDORT, Bi-Digital-O-Ring-Test; CBT, Cognitive Behavioral therapy; CBT-SD, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy integrated with systematic desensitization; VRET, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy +virtual reality exposure therapy; COMET, Competitive Memory Training .

The first study was carried out by Feske and Goldsteina ( 1997 ) in a sample of 43 patients with a diagnosis of panic disorder with agoraphobia. The diagnosis was established when symptoms were present for at least 1 year and at least one panic attack had occurred during the 2-week pre-test monitoring period. The subjects were randomized to EMDR therapy, eye fixation exposure and reprocessing therapy (EFER) (a version of EMDR omitting the ocular movements) or WL. The main aims of this study were to assess the efficacy of EMDR therapy in panic disorder and to analyze whether or not this correlates with the eye movements. Patients in both experimental groups, received five sessions over an average period of 3 weeks (one session of 120 min and four of 90 min). Authors found a significant improvement in post-treatment measures when comparing the EMDR group with the WL group ( p < 0.05). ANCOVAS test revealed that the EMDR group was superior to the EFER group on 2 out of 5 primary measures of anxiety, specifically in the Agoraphobia-Anticipated Panic-Coping Composite ( F = 7.65, p = 0.009) and General Anxiety-Fear of Panic Composite ( F = 5.28, p = 0.028), on secondary measures of depression (BDI F = 4.96, p = 0.033), and on social adjustment, measured by the Social Adjustment Scale, Self-Report ( F = 5.96, p = 0.020). However, at 3 months follow up, results did not remain significant.

Goldstein et al. aimed to replicate these results in 46 outpatients with a panic disorder and agoraphobia. Patients were randomized to EMDR therapy (6 sessions lasting 90 min conducted along 4 weeks), a credible attention-placebo control group or to a WL condition (Goldstein et al., 2000 ). The attention-placebo condition, consisted in a combination of 30–45 min of progressive muscle relaxation training and 45–60 min of association therapy. Compared to the WL condition, patients in the EMDR group showed a significant improvement on the measures of severity of anxiety, panic disorder and agoraphobia ( F = 9.91, p ≤ 0.01), but the authors did not find significant changes in panic attacks frequency ( F = 1.3, p ≥ 0.05) nor in anxious cognitions ( F = 2.69, p ≥ 0.05). They found that EMDR therapy was superior to WL with a medium to large effect for all anxiety measures. ANOVAs test did not show any significant differences between EMDR therapy and the credible attention-placebo control condition (all measures: cognitive measures, panic and agoraphobic severity, diary and panic frequency were p > 0.13). Although EMDR therapy was superior to the WL condition, they concluded, based on their results, that EMDR therapy should not be the first-line treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia.

One RCT so far has compared EMDR therapy with other psychotherapies to treat flight anxiety (Triscari et al., 2015 ). Of 65 patients, 22 patients were randomized to cognitive behavioral therapy integrated with systematic desensitization (CBT-SD), 22 patients to CBT with EMDR therapy (CBT-EMDR) and 21 patients to CBT combined with virtual reality exposure (CBT-VRET). All patients were assessed with the Flight Anxiety Situations Questionnaire and with the Flight Anxiety Modality Questionnaire. They received 10 weekly sessions of 2 h duration. No mean differences were found between the three groups after treatment or at follow-up, but all interventions showed efficiency in reducing fear of flying, demonstrating a high effect size (Cohen's d ranged from 1.32 to 2.23).

Another RCT has been performed in dental phobia (Doering et al., 2013 ). Sixteen patients were randomized to 3 weekly sessions of EMDR therapy, 90 min each, and 15 patients to a non-interventional WL. All patients were assessed with the Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS) and the Dental Fear Survey (DFS), secondary measures were assessed with the Brief Symptom Inventory and the Clinical Global Impression Score. Anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed with the German Version of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, symptoms of PTSD with the Impact of Event Scale-Revised and dissociative symptoms with the German Version of Dissociative Experiences Scale. The EMDR group demonstrated a significant decrease of dental anxiety scales with an effect size of 2.52 and 1.87 in DAS and DFS, respectively ( p < 0.001). The effect sizes after 3 months (DAS 3.28 and DFS 2.28) and after 12 months (DAS 3.75 and DFS 1.79) persisted among the follow-up ( p < 0.001). The most important result of this study was that a high number of patients overcame their avoidance behavior and visited the dentist regularly following treatment.

Furthermore, a recent trial compared EMDR therapy and competitive memory training (COMET) in the treatment of anxiety disorders with the purpose to improve self-esteem (Staring et al., 2016 ). The authors included 47 patients with a primary anxiety disorder and low self-esteem, which were assessed by the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale, the Self-esteem Rating Scale-short Form and the STAI. Depressive symptoms were evaluated with BDI-II. Patients were randomized in a crossover design. Twenty-four patients received 6 EMDR therapy sessions and then 6 COMET sessions, the other 23 patients received firstly 6 COMET sessions and then 6 EMDR therapy sessions. COMET was more effective in improving self-esteem than EMDR therapy (effect sizes of 1.25 vs. 0.46, respectively). When EMDR therapy was applied before COMET, the effects of COMET on self-esteem and depression were significantly reduced. It could be hypothesized that EMDR therapy could diminish the effectiveness of the COMET intervention.

Finally, 1 RCT was performed in obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) (Nazari et al., 2011 ). They recruited a sample of 90 patients who were randomized to a treatment condition with Citalopram (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) or EMDR therapy during 12 weeks. All subjects were assessed with the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale before and after the treatment. They observed that both treatments were effective to treat obsessive symptoms, but the EMDR therapy group showed a faster improvement of obsessive and compulsive symptoms than the group treated with Citalopram ( p = 0.001).

In summary, EMDR therapy has demonstrated in 4 RCT a positive effect on anxious and OCD symptoms (Feske and Goldsteina, 1997 ; Nazari et al., 2011 ; Doering et al., 2013 ; Triscari et al., 2015 ), whereas 1 RCT in panic disorder with agoraphobia was in part negative (Goldstein et al., 2000 ) and another study failed in improving self-esteem in patients with anxiety disorders (Staring et al., 2016 ).

EMDR therapy in substance use disorders

Two studies so far have explored the efficacy of EMDR therapy in substance use disorders (Hase et al., 2008 ; Perez-Dandieu and Tapia, 2014 ). In a first study, 34 alcohol addicted patients were randomly assigned to TAU or TAU plus two sessions of EMDR therapy (Hase et al., 2008 ). The overall aim was to assess the craving intensity for alcohol via the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS) at pretreatment, post-treatment, and follow-up at 1 and 6 months. Likewise, other variables such as depression or anxiety symptoms were analyzed. Compared to pretreatment, post-treatment scores of craving and depression revealed a significant improvement in the experimental group (OCDS t = 10.7, p < 0.001; BDI t = 4.0, p = 0.001), while only a small reduction in both measures was noticed in the control group (OCDS t = 1.1, p = 0.29, BDI t = 0.9, p = 0.37). Between both groups, the difference in OCDS scores post-treatment was statistically significant ( p < 0.001). These differences were maintained at 1-month follow-up ( p < 0.05) but not at 6 months.

In a second study, 12 alcohol and/or drug addicted women with PTSD were randomized to TAU or TAU plus eight sessions of EMDR therapy (Perez-Dandieu and Tapia, 2014 ). Outcome criteria were PTSD symptoms, addiction symptoms, depression, anxiety, self-esteem [measured with Coopersmith's Self-esteem Inventory (SEI)] and alexithymia [assessed by Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS)]. Compared to pretreatment, PTSD scores showed a significant improvement in the experimental group compared to the control group (TAU+EMDR t = 4.22, p = 0.008; TAU t = −0.94, p = 0.38). Between both groups, the difference in the post-treatment PTSD scores, was also statistically significant ( p < 0.01). Regarding addiction symptoms, no differences between both groups were detected. Finally, regarding the measures of depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and alexithymia, the experimental group showed a significant improvement in all of them except in the TAS (BDI t = 4.38, p = 0.007; STAI t = 2.65, p = 0.04; SEI t = −3.37, p = 0.01). On the contrary, the control group showed no significant differences in any measure. Between both groups, only the difference in post-treatment BDI scores were statistically significant ( t = 14.13, p < 0.004).

Considering the results of both studies, EMDR therapy could be a useful therapy to use in substance use disorders with a history of traumatic life events in order to improve the prognosis of these patients (Perez-Dandieu and Tapia, 2014 ). Besides, EMDR therapy could help as an adjuvant psychotherapy to standard treatment of alcohol dependence directly decreasing craving (Hase et al., 2008 ; Table 2 ).

EMDR therapy and chronic pain

One RCT has investigated so far the efficacy of EMDR therapy in the treatment of patients suffering from chronic pain (see Table 2 ; Gerhardt, 2016 ). Forty patients with chronic back pain and psychological trauma were randomized to 10 sessions of EMDR therapy in addition to TAU or TAU alone. The participants were re-assessed 2 weeks after study completion and also at 6 months follow-up after the end of the treatment. The primary outcome was its efficacy in pain reduction, measured by pain intensity, disability and treatment satisfaction. Estimated effect sizes between groups for pain intensity and disability were d = 0.79 (Ci 95%: 0.13, 1.42) and d = 0.39 (CI 95%: −0.24, 1.01) at post-treatment and d = 0.50 (CI 95%: 0.14, 1.12) and d = 0.14 (Ci 95%: −0.48, 0.76) at 6 months follow-up. Evaluation on treatment satisfaction from the patient's perspective showed that about 40% of the patients in the EMDR group in addition to TAU improved clinically and also rated their situation as clinically satisfactory, whilst in the control group, no patients showed clinical improvement. In view of these results, the authors concluded that EMDR therapy is a safe and effective therapeutic strategy to reduce pain intensity and disability in patients with chronic back pain.

This systematic review aimed to describe briefly the current evidence regarding EMDR therapy in patients with psychiatric conditions beyond PTSD but with a history of comorbid traumatic events. Even though RCT of EMDR therapy in severe mental disorders beyond PTSD are still scarce, an increased trend of publications at last decade has been observed. In general terms, we can conclude that there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend EMDR therapy as a treatment of choice in psychotic disorders and, so far, the same occurs with bipolar disorders (Kim et al., 2010 ; de Bont et al., 2013 ; Novo et al., 2014 ; van den Berg et al., 2015 ; Van Minnen et al., 2016 ). However, a large trial is being currently conducted in order to reach more accurate conclusions (Moreno-Alcazar et al, 2017 ).

The largest RCT of EMDR therapy in other psychiatric disorders has been performed in patients suffering from a psychotic disorder and a comorbid PTSD (van den Berg et al., 2015 ). Trauma-associated symptoms but also paranoid thoughts improved equally in both active comparators, EMDR and PE, when compared to WL. Both interventions were considered as safe. Both treatments were also effective in reducing PTSD symptoms with no significant differences between them in terms of effect or safety. The lack of superiority of EMDR therapy over the other treatment condition might be due to the fact that this study only applied 3 EMDR therapy sessions, which might be insufficient and infratherapeutic considering the symptomatic complexity of the sample, suffering from both schizophrenia and PTSD. In the subanalysis of the study, the authors pointed out that patients with a dissociative subtype of PTSD had a similar and favorable response to trauma focused treatments than those without the dissociative subtype, so this subgroup could benefit from this treatment and should not be excluded. These results are clinically relevant considering that patients with a psychotic disorder frequently suffer from comorbid adverse events/PTSD which affects in a negative way the course of the illness. Unfortunately, this is rarely taken into account when clinicians develop a personalized therapeutic plan, as therapists often believe treating traumatic events might deteriorate the patient's psychopathological state.

Similar to psychotic disorders, bipolar patients experience comorbid PTSD with a prevalence of 20% approximately (Hernandez et al., 2013 ; Passos et al., 2016 ; Cerimele et al., 2017 ). PTSD symptoms as well as life events cause more affective episodes (Simhandl et al., 2015 ). Therefore, trauma-orientated interventions need to be integrated in treatment strategies for bipolar patients. Positive evidence of trauma-orientated therapies, such as CBT and cognitive restructuring, exist in both psychotic and bipolar disorders with comorbid PTSD, these interventions have proven to be effective and safe (Mueser et al., 2008 , 2015 ). Additionally, EMDR therapy has also been tested to treat traumatic symptoms in this population. Hereby in a pilot RCT including patients with a bipolar disorder (types I and II) with subsyndromal symptoms and a history of traumatic events, the authors found that patients showed an improvement in comparison to the TAU condition (Novo et al., 2014 ) and did not develop any mood episode related to the EMDR therapy. Given these results, EMDR therapy could be a promising and safe therapeutic strategy to reduce trauma symptoms and stabilize mood in traumatized bipolar patients, which is why a specific EMDR bipolar protocol has been suggested (Batalla et al., 2015 ). Currently, this EMDR protocol is being tested vs. supportive therapy in a large multicenter RCT including bipolar patients with a history of traumatic events (Moreno-Alcazar et al., 2017 ).

In depressive disorders, one study demonstrated the effectiveness of EMDR therapy compared to psychodynamic psychotherapy, group therapy, and psychoeducation therapy (Hase et al., 2008 ). EMDR therapy improved memories of stressful life events at onset of depressive episodes, emotional cognitive processing and long-term memory conceptual organization (Hase et al., 2008 ).

Within anxiety disorders, conflicting results were found in panic disorders with agoraphobia as it seems that EMDR therapy decreases severity of anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia but not panic attacks frequency and anxious cognitions. Authors recommended EMDR therapy as an effective alternative to treat panic disorder with agoraphobia when other evidence-based treatments, such as exposure therapy or cognitive-behavior therapy, had failed. Nevertheless, panic disorder studies were not able to demonstrate an effect of EMDR therapy on anxious cognitions, as you would expect to find after applying the therapy. In OCD or phobias studies we did not find this fact. Further larger trials are needed to answer whether or not EMDR therapy is a valid therapeutic option as first line treatment in anxiety disorders and OCD.

Evidence of RCT so far suggests that EMDR therapy is a useful tool in the treatment of specific phobias, like flight anxiety or dental phobia, whether or not related to PTSD symptoms (Doering et al., 2013 ; Triscari et al., 2015 ).

In substance use disorders, EMDR therapy has been tested mainly in alcohol use disorders (Hase et al., 2008 ). EMDR therapy appears hereby to be useful as it decreases craving and drinking behavior (Hase et al., 2008 ; Perez-Dandieu and Tapia, 2014 ).

Finally, EMDR therapy was also effective in a first RCT for the treatment of chronic back pain (Gerhardt, 2016 ). This is not surprising as the impact of stress on both mental and physical health has been acknowledged for many years (Schneiderman et al., 2005 ). Pain as consequence of a traumatic event has been hereby identified as a risk factor for the development of PTSD (Norman et al., 2008 ) and often PTSD and chronic pain are concomitant (Beckham et al., 1997 ; Beck and Clapp, 2011 ; Moeller-Bertram et al., 2012 ). Again, further trials are needed to confirm the efficacy of EMDR therapy in this complex and often difficult to treat population.

The main limitation of this review is that RCT are scarce so far; however, as the use of EMDR therapy is increasing and gaining popularity, this systematic review is timely. Another limitation is that some of the included studies had very few therapeutic sessions. The high heterogeneity in number and duration of EMDR therapy sessions could have a negative effect on the results, so these must be taken cautiously (Hase et al., 2008 , 2015 ; Kim et al., 2010 ; Behnammoghadam et al., 2015 ).

In general, EMDR therapy seems a safe intervention (Feske and Goldsteina, 1997 ; Hase et al., 2008 , 2015 ; Doering et al., 2013 ; Novo et al., 2014 ; Perez-Dandieu and Tapia, 2014 ; Triscari et al., 2015 ; van den Berg et al., 2015 ; Gerhardt, 2016 ). This is of importance as it allows clinicians to consider EMDR therapy as an appropriate treatment in various psychiatric comorbid conditions without causing side effects.

Author contributions

AV has performed the bibliographic search and has elaborated the first draft of the manuscript. AM has participated in the selection of included studies, resolved methodological doubts of possible studies, and helped in the first version of this manuscript. DT helped in the development of this review and revised the manuscript as native speaker. CC has collaborated in methodological aspects of this article. VP and FC have contributed in the improvement of the manuscript and BA had the idea of this work and revised the last version of this article.

Conflict of interest statement

BA has been invited as speaker to several national and international EMDR congresses. VP has been a consultant or has received honoraria or grants from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, and Medtronic. The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Plan Nacional de I+D+i and co-funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III-Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación with the following Research Project (PI/15/02242). We acknowledge also the generous support by the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid, Spain. Furthermore, BA received a NARSARD Independent Investigator Award (n° 24397) from the Brain and Behavior Research Behavior and a further support from EMDR Research Foundation and from EMDR Europe all of which are greatly appreciated.

1 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/trauma_mental_health_20130806/es/2013 .

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01668/full#supplementary-material

- Assion H. J., Brune N., Schmidt N., Aubel T., Edel M. A., Basilowski M., et al. (2009). Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in bipolar disorder. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 44, 1041–1049. 10.1007/s00127-009-0029-1 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Batalla R., Blanch V., Capellades D., Carvajal M. J., Fernández I., García F., et al. (2015). EMDR therapy protocol for bipolar disorder, in Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy Scripted Protocols and Summary Sheets: Treating Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive, and Mood-Related Conditions, ed Luber M. (New York, NY: Marilyn Luber; ), 223–287. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck J. G., Clapp J. D. (2011). A different kind of co-morbidity: understanding post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Psychol. Trauma 3, 101–108. 10.1037/a0021263 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beckham J. C., Crawford A. L., Feldman M. E., Kirby A. C., Hertzberg M. A., Davidson J. R., et al. (1997). Chronic post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain in Vietnam combat veterans. J. Psychosom. Res. 43, 379–389. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Behnammoghadam M., Alamdari A. K., Behnammoghadam A., Darban F. (2015). Effect of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) on Depression in Patients With Myocardial Infarction (MI). Glob. J. Health Sci. 7, 258–262. 10.5539/gjhs.v7n6p258 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benish S. G., Imel Z. E., Wampold B. E. (2008). Corrigendum to “The relative efficacy of bona fide psychotherapies for treating post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of direct comparisons.” Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28, 766–775. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradley R., Greene J., Russ E., Dutra L., Westen D. (2005). A multidimensional meta- analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 214–227. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cerimele J. M., Bauer A. M., Fortney J. C., Bauer M. S. (2017). Patients with co-occurring bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder: a rapid review of the literature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 78, e506–e514. 10.4088/JCP.16r10897 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen L., Zhang G., Hu M., Liang X. (2015). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs. cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult post-traumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 203, 443–451. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000306 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen Y. R., Hung K. W., Tsai J. C., Chu H., Chung M. H., Chen S. R., et al. (2014). Efficacy of eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing for patients with post-traumatic-stress disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 9:e103676 10.1371/journal.pone.0103676 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davidson P. R., Parker K. C. H. (2005). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): a meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 69, 305–316. 10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.305 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]