- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

Designing Care: The Importance of Humanization in Healthcare Spaces

- Written by Adele Belitardo | Translated by Diogo Simões

- Published on January 22, 2024

Silent and endless hallways, white and cold rooms, an impersonal and distant atmosphere: this is a deeply ingrained image in our cultural conception of hospital environments. The whiteness of these spaces, attempting to reinforce the necessary notions of sterility and cleanliness, may also evoke a sense of discomfort and anxiety for patients and their families.

The importance of humanizing hospital, clinic, and office projects is an increasingly discussed and relevant topic in healthcare, extending far beyond the aesthetics of these buildings. It is necessary to create welcoming environments that promote the well-being of patients, families, and professionals, recognizing that architecture can play a fundamental role in the recovery and comfort of these individuals during moments of vulnerability.

Studies in neuroarchitecture delve into the connection between the built environment and brain function, focusing on emotional, cognitive, and physiological responses. In healthcare projects, there is a strong emphasis on creating spaces that promote calmness, concentration, and a sense of security , which involves employing colors, textures, and layouts to minimize feelings of confinement and enhance the perception of control over the environment. For example, using soft and soothing colors can alleviate anxiety, and a well-thought-out spatial arrangement can improve patient orientation and streamline the work of healthcare professionals.

Biophilia also underlies humanization in these projects, recognizing humans' innate affinity with nature and acknowledging that the presence of natural elements in built environments can enhance people's health and well-being. In healthcare areas, architects can incorporate elements such as natural light, greenery, outdoor views, and organic materials, which can reduce stress, improve mood, and expedite patients' recovery process. Additionally, comfortable waiting areas and indoor gardens can provide relaxation and emotional relief, conveying empathy and care.

Humanization in the design of clinics, offices, and hospitals aims to create spaces that promote the recovery, comfort, and well-being of patients, families, and professionals. However, it is crucial to emphasize that this humanization goes beyond the physical aspects of the buildings; it also extends to the organizational culture of institutions. Healthcare professionals must foster a welcoming and humanized environment where effective communication and respect for the patient are priorities.

Architects can help improve healthcare quality and patient recovery by incorporating specific elements and concepts. Below, we have selected five healthcare projects that, with thoughtful and deliberate choices, have made their environments more welcoming and effective.

Maggie’s Leeds Centre / Heatherwick Studio

"The interior of the centre explores everything that is often missed in healing environments: natural and tactile materials, soft lighting, and a variety of spaces designed to encourage social opportunities as well as quiet contemplation. Window sills and shelves are intended for visitors to fill with their own objects to create a sense of home."

New Lady Cilento Children's Hospital / Lyons + Conrad Gargett

"Its brightly colored exterior, incorporating the green and purple coloration of the native Bougainvillea plantings in the adjacent parklands, speaks of a building designed for children. The design uses a "salutogenic" approach, incorporating design strategies that research has shown to directly support patient health and well-being. Two and three-dimensional art is used extensively throughout the building to promote patient wellbeing and provide engaging distractions for young patients."

Clinic in the Woods / Takashige Yamashita Office

"Mixed up with the small forests introduced in between the volumes and soaring through the roof, the treatment rooms offer a calm, comfortable scene embraced in nature that would soothe the anxiety of little patients."

PAMS Healthcare Hub, Newman / Kaunitz Yeung Architecture

"The building is predominantly rammed earth, the original building material, abundant, free, and sustainable. However, its value to the project is much more profound than this. Rammed earth creates a human and intuitive connection to its place. The material is country. It reflects the different light and absorbs the rain just like a country. This is obvious and immediate to everyone but elevated and important for Aboriginal people. A place for the community to be proud of and welcome in. A place that puts wellness at the center of the community."

Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen / Vilhelm Lauritzen Architects + Mikkelsen Architects + STED

"Studies show that traditional hospital settings can make healthy patients feel ill and weaken them physically and emotionally. Therefore, user involvement has been the common thread throughout the creation of SDCC with an emphasis on ensuring a pleasant experience in all stages of arrival, waiting, and consultation. The design rethinks the function of common areas, converting waiting time to active time and supporting a natural flow of activities around the themes of diet, exercise, and new knowledge."

The excerpts were taken from the project memorials.

Image gallery

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

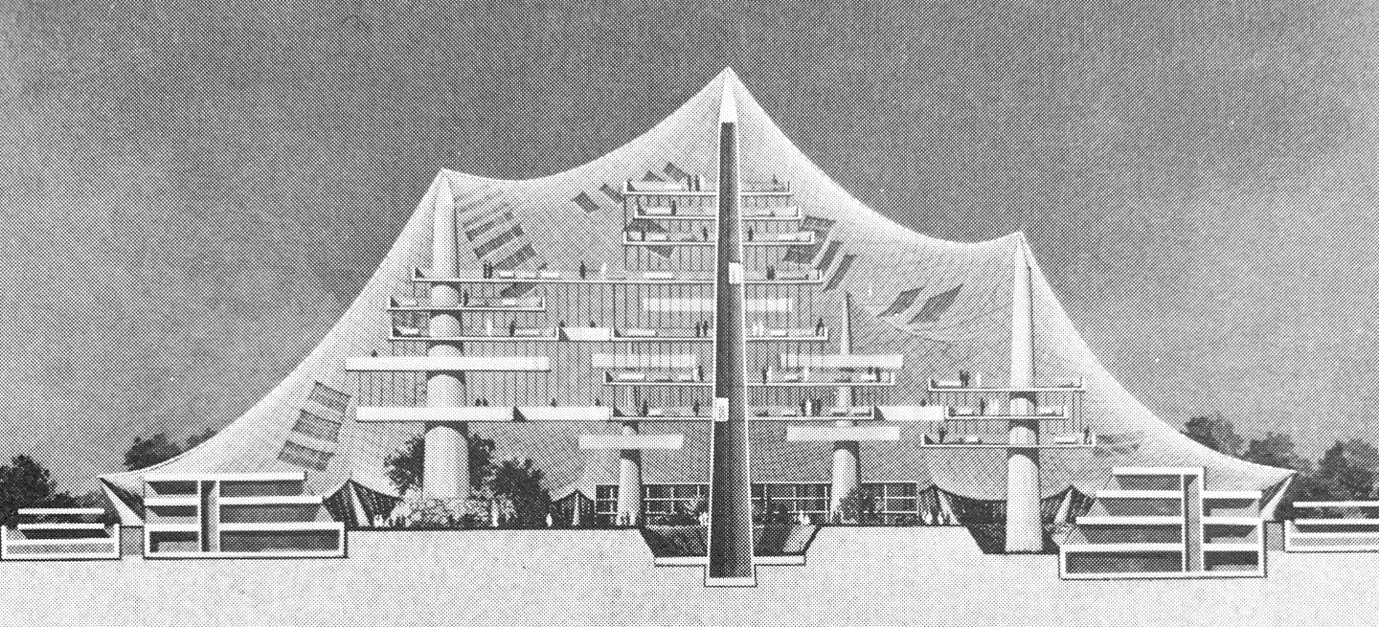

10 forward-thinking design trends in hospitals today

For more than a century, we have seen paradigm shifts and pivots in healthcare and the concept of the hospital as a typology. Going back to the 1800’s, sanitation and hygiene were recognized as being beneficial to overall health. The flu pandemic of 1918 brought recognition of the importance of light and ventilation. Le Corbusier and the International school drove forward the machine aesthetic in architecture. In reaction to that, Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanitarium for tuberculosis emphasized the role a building can play in the healing process, with the building acting as a ‘medical instrument’. In the 1940’s architect Charles Neergaard rejected the concept of natural ventilation and daylight as representative of health and proposed a hospital with windowless inpatient rooms. Through the 1950’s, we saw a transition towards more enclosed building with integration of HVAC environmental controls, which further removed the humanity from the environment. In the 1960’s, Le Corbusier proposed the “New Venice Hospital” reintegrating light through venetian square or courtyards and skylights. In the 1970’s E. Todd Wheeler even imagined a Tropicarium, or tent hospital made of tree-like structures served by drones, as a way to return to nature –which in the current atmosphere of COVID alternate care facilities may not be so unrealistic. In recent years we have seen a return to biophilia and natural environments.

Now, as we look ahead, here are the key trends in healthcare we expect to see:.

The healthcare industry was one of the first markets to embrace resilience and RELi rating system. COVID-19 has further reinforced the importance of resilience in hospitals. The Rush University Medical Center Tower , which opened in 2012, is a perfect example. The building, which was designed in the aftermath of 9/11 for bioterrorism events and pandemics, was readily converted to accommodate surge capacity and negative pressure patient treatment areas in the early days of the COVID 19 pandemic.

As data becomes more accessible and institutions continue to weigh the value of design decisions, we expect to see an expansion in the use of evidence-based design (EBD) and data in healthcare. Such research and neuro-architecture principles, along with input from a Patient and Family Advisory committee, were used as guideposts throughout the design and construction of the UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute , ensuring each decision was made to support the unique patient population served in the building.

With the continued globalization of healthcare, we expect to see merging of local culture, conditions, and building methodologies with the advanced care, high safety standard and cutting-edge medical planning across the world. There are lessons to be learned from all countries and cultures. In the era of COVID, Singapore’s open-air inpatient units and outdoor spaces could be a well-tested solution to our ventilation concerns surrounding airborne diseases, where the climate allows it.

Leading up to the pandemic, there was an increased focus on prevention and holistic wellness, with healthcare institutions investing in facilities like the Piedmont Wellness Center in Fayetteville, GA. This state-of-the-art facility offers fitness and sports training, nutritional counseling, and outpatient rehab services all surrounded by hiking trails dotted with art installations. The COVID pandemic has certainly turned the $4.5 trillion wellness industry on its head, but we expect to see the continued growth of community health and wellness, just in new ways and locations

January 21, 2020 was the first reported case of coronavirus in the US. Just under 11 months later, on December 14, 2020, the first vaccine was administered. Our lesson? The often life and death importance of integrated science and research in medicine. We’re hopeful that COVID will serve as a catalyst for expansion of translational medicine and research.

Even before COVID, we were experiencing worldwide healthcare staffing shortages. have shown that by 2030, 23 of 50 states will have critical shortages of physicians , with 30 states facing nursing shortages . After a decade’s long focus on patient experience, experiential design can be expected to expand its focus to creating staff spaces that support recruitment and retention. Robotics and A.I. may be expanded to supplement staff and help to reduce transmission of infection in case of future pandemics.

Technology is advancing at a rapid pace – bionics, robots to clean hospitals and lift patients, and microchip implants, to name a few, are all now a reality. The impact of more yet-to-be-discovered technologies is a mystery to us all.

COVID forced the implementation of telehealth far faster than may have happened otherwise, but we think it is here to stay.

To complement this technology-driven culture, we’re witnessing a resurgence of nature and biophilia in healthcare spaces. While not quite the open-air natural environment that E. Todd Wheeler dreamed of with his Tropicarium, The Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford seamlessly links gardens and terraces with clinical spaces – providing a natural, healing environment for patients and staff alike.

According to Scripps Health, adults spend an average of 11 hours a day staring at a screen. Healthcare is not immune to this reliance on immediate access and the internet of things. We expect to see continued growth of wearable technology, access to providers and medical records, and connectivity between personal health data and healthcare.

While infection control is not a new concept, COVID has made us hyper aware of the materials we select for all spaces, be they healthcare or not. The University of Virginia Health System’s Hospital Expansion Project in Charlottesville, VA, is a perfect example. The lobby, with its light-colored wood ceiling and warm white floors and walls, isn’t just beautiful, it’s also functional as overflow for the ED, and features cleanable, durable materials.

Related Content