3 Ways to Save Time In Your Literature Reviews

by Joanna Lansche | Feb 7, 2019

Demand for evidence has been increasing steadily in recent years, and it shows no signs of stopping. Evidence-based research is informing decisions and policy in a wide range of fields and is increasingly used by medical device and pharmaceutical companies to demonstrate product safety.

Systematic literature reviews are central to the evidence generation process. Researchers spend countless hours on literature review tasks such as developing an effective search strategy, screening titles and abstracts, extracting data, and preparing reports. Whether you’re screening thousands of references for guideline development or preparing regulatory submissions for a dossier of hundreds of products, conducting a rigorous literature review requires a significant investment of time.

So, for all of you researchers who are desperate to add a few extra hours to your day, here are three easy things you can do to get your reviews done faster (and free up some time!)

1. Rapid Title Screening

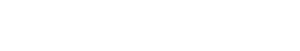

It can be very time-consuming to screen your search output to identify records relevant to your research questions, especially when your search returned hundreds or thousands of references. Excluding references that obviously don’t apply to your review right off the bat can save considerable time and resources, and you can often identify records that are clearly irrelevant just by their title.

Rapid title screening using literature review software allows you to conduct an initial screen of your search output by presenting you with a list of reference titles only as the first stage of your review. You can quickly flag clearly irrelevant titles for immediate exclusion, while retaining any that appear potentially relevant for full title and abstract screening. Less reading = more time.

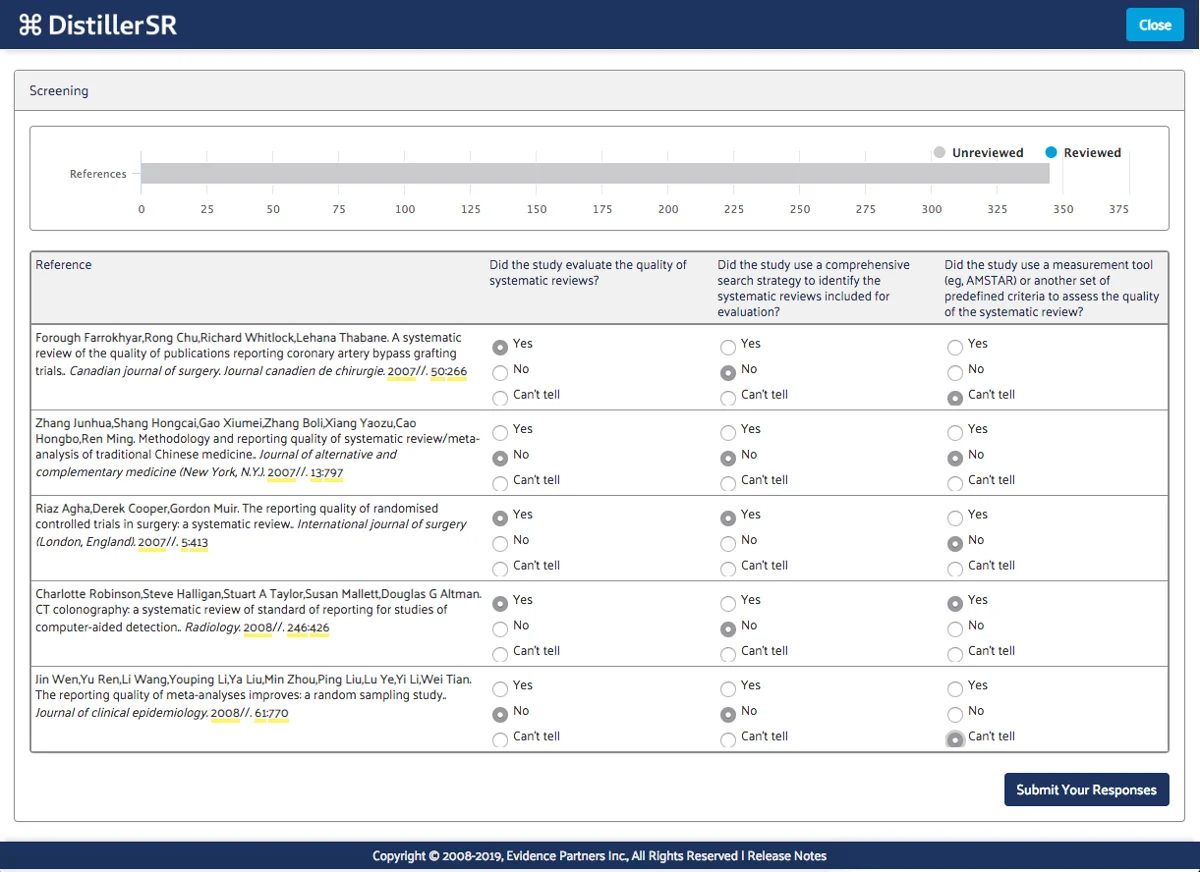

2. Dynamic Questions

Ever been handed a survey where half the questions don’t apply to you? It can be a waste of your time when you’ve selected ‘no’ to a particular question to then be required to answer a number of subsequent questions that aren’t relevant.

The same applies to your screening or data extraction forms.

Luckily, if you use literature review software, questions can be set to dynamically appear only when specific conditions are met, so you don’t have to waste time answering, or even seeing, questions that don’t apply.

For example, if an exclusion answer has already been chosen there may be no reason to answer any additional questions. Or, if your reference set includes records with different study designs, populations, or outcomes, dynamic questions can be used to take you directly to the next applicable question or form once you’ve made a particular selection.

Constructing forms with hidden questions saves a great deal of real estate and time spent searching for the next applicable question. Once you’ve collected exactly the data you need from each reference, you can more quickly continue on with your review process.

3. Reusing previously extracted data

If you’re conducting (or planning to conduct) another review on a similar topic or in a similar domain, you don’t want to review the same records more than once – you’ve already put in the work. Each time you extract data , you’re coding it (that is, creating structured data from unstructured text). Literature review software makes it easy to search and reuse records and their extracted data across multiple reviews.

Think about searching PubMed. You can search using any of the available fields in the reference set. A coded reference (i.e. one that has had data extracted during a review process) is like a PubMed record, only instead of having only the PubMed fields, it has fields for every piece of data that you have extracted. This makes it easier to find specific data about a reference and to search a group of references with more precision.

Literature review software not only makes it possible to store references with their extracted data, but it can also be configured to populate questions on screening and data extraction forms using data that has already been coded. This can save you from manually copying and pasting, or worse, screening and extracting data from the same reference twice.

Put these tips to the test in your literature review process and we’ll bet you see noticeable gains in the efficiency of your review.

Joanna Lansche, our Product Owner, brings a thirst for knowledge and a critical eye to the team. With a background in Communications and experience in writing, content production, and workshops, she is dedicated to producing in-depth and educational content. In her spare time, she enjoys singing, camping, cheering for the Ottawa Senators, and engaging with a variety of media.

Stay in Touch with Our Quarterly Newsletter

Recent posts.

Here’s Why You Should Stop Relying on Spreadsheets for Your Literature Review Process

We understand—spreadsheets are readily available as part of most standard office suites and are easily ‘customized’ to do specific tasks using formulas and macros. It can be very tempting to fall back on them as your default tool for literature reviews – especially...

Webinar Recap: Stryker and IQVIA Share Their Journey Leveraging Data Reuse for Faster Insights, Time to Market and Healthcare Innovation

At a recent webinar with Sepanta Fazaeli, Clinical Systems & Medical Systems Lead at Stryker and Rajpal Singh, Associate Director at IQVIA, moderated by Mark Priatel, VP of Software Development at DistillerSR, we explored the benefits of centralizing literature...

EM’24 Medical Devices/IVD Industry Best Practices Session Recap

The Evidence Matters 2024 Medical Devices/IVD Best Practices session featured industry experts Rea Castro, Director of Medical Affairs at QuidelOrtho, Sepanta Fazaeli, Clinical Systems & Medical Lead at Stryker, and Christa Goode, Worldwide Scientific Operations...

Why is the literature review important?

Why is the Literature Review Important?

In academic research, a literature review is a comprehensive analysis of previous research related to the current study or project. It is a fundamental part of the research process, as it provides a solid foundation for the research, helps to identify gaps in current knowledge, and ensures that the research contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the field. In this article, we will explore the importance of literature reviews, their benefits, and the various types of literature reviews.

Direct Answer: Why is the Literature Review Important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Frames the research question : By analyzing existing research, a researcher can identify the key issues, debates, and gaps in the field, which helps to formulate a clear and focused research question.

- Provides a comprehensive overview of the research area : A literature review provides an in-depth analysis of the existing research in the field, allowing researchers to understand the current state of knowledge and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Identifies gaps and inconsistencies : A thorough literature review helps to identify gaps in current knowledge, contradictions in previous research, and areas of controversy, which can inform the research design and methodology.

- Avoids repetition and duplication of research : By building on existing knowledge, researchers can avoid conducting redundant research and instead focus on filling gaps and advancing the field.

- Enhances the rigor and validity of the research : A well-conducted literature review can increase the credibility and impact of the research by demonstrating a deep understanding of the research area and a commitment to quality and integrity.

- Supports the development of a research hypothesis : A literature review can inform the development of a research hypothesis by identifying the relationships between variables, the impact of variables, and the potential for mediating or moderating effects.

Benefits of a Literature Review

A well-conducted literature review offers numerous benefits, including:

- Improved research design : A literature review helps to ensure that the research design is sound, relevant, and practical.

- Enhanced research quality : By building on existing knowledge, researchers can increase the rigour and validity of their research.

- Increased impact : A well-conducted literature review can increase the impact of the research by demonstrating a deep understanding of the research area.

- Better research communication : A literature review can facilitate effective communication with other researchers, stakeholders, and the broader community.

Types of Literature Reviews

There are various types of literature reviews, including:

- Narrative review : A narrative review provides an overview of the existing research in a particular field, summarizing the key findings, debates, and gaps.

- Systematic review : A systematic review uses a systematic and transparent approach to identify, evaluate, and synthesize the results of multiple studies.

- Meta-analysis : A meta-analysis involves combining and analyzing the results of multiple studies to draw a conclusion that is stronger than any single study.

- Mixed-methods review : A mixed-methods review combines qualitative and quantitative research studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research area.

In conclusion, a literature review is a crucial component of the research process, providing a solid foundation for the research, identifying gaps in current knowledge, and ensuring that the research contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the field. By understanding the importance of literature reviews, researchers can ensure that their research is informed, rigorous, and relevant, leading to more effective and impactful contributions to the field.

Table: Benefits of a Literature Review

What did you learn from this article?

In this article, we explored the importance of literature reviews in research, their benefits, and the various types of literature reviews. By understanding the importance of literature reviews, researchers can ensure that their research is informed, rigorous, and relevant, leading to more effective and impactful contributions to the field.

- How to listen to apple music on windows 10?

- Does mike ross go to law school?

- How to add custom music to ultrakill cybergrind?

- How to watch Apple TV on Samsung tv?

- How to get concentration chemistry?

- Where is the university of baylor?

- Canʼt see profile views TikTok?

- How do I recover my Wifi password?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Literature Review: The What, Why, Where, How, and When to Stop Writing It

This article comprehensively describes the what, why, where, and how of literature review. In addition, it provides tips on when to stop writing it with a supplemental video. Read on and stop wasting your time looking for tidbits of information about this essential part of research writing.

Yes. What I tell you is the truth. I wrote this article just for you to spare you from jumping from one page to another page in Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or whatever your favorite browser is looking for information about the literature review.

The other day, it dawned upon me that I’d better put all my literature review notes in this article for the maximum benefit to readers. I diligently searched information online, from printed books and e-books, in addition to my experience writing this portion of research or thesis. Here’s the place I write all the information I have gathered.

If I missed anything, feel free to comment below. I’ll incorporate your suggestion as long as it doesn’t duplicate what I have discussed.

I originally wrote this article for my students as part of my innovative approach to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. I call it the Blended Website Learning System . It just works as students learn both synchronously, semi-synchronously, and asynchronously despite the challenges of online learning.

Synchronous learning means real-time lectures with interaction via Zoom, and asynchronously when students read and accomplish the modules with guideposts that I have prepared for specific subjects. Semi-synchronous learning means the student initially connects, loses connection due to a poor internet connection, then connects again. I patch up by recording the discussion and uploading it for my students to download and listen to the complete proceedings.

Given the nature of this topic, this article will be invaluable information to students or colleagues looking for information about literature review as an essential part of a research, for free. Those unfortunate students in the remotest places on earth who have difficulty accessing the internet will greatly benefit. More so at this time when virtually everyone taking advanced studies takes refuge to online material due to the pandemic .

Now let’s zero in on the literature review: the What , Why , Where , How , and When to stop writing it. If you are in the process of writing your literature review, you may jump right to the information you want using the table with linked topics below.

What is a literature review?

Literature review defined.

The literature review is a critical survey of the existing and preferably current (3-5 years) scientific literature on a previously identified research topic or variable . In a thesis, it is usually found in Chapter 2. In condensed, article versions of a research paper published in a scientific journal, the review of literature integrates with the introduction or background of the study.

The literature review explores what researchers all over the world have done so far to explain a given phenomenon using a method that systematically examines how it occurs. Thus, it contains different theories and methodologies that help unravel the mystery of unexplained facts or events.

A literature review is a critical description of the literature about the research topic that you as a researcher chose to work on as part of your thesis proposal or research paper. Emphasis is given to the word “critical.” This implies that you have read a great deal of literature such that you can see the issue at hand and make an informed assessment.

Why do you have to write the literature review?

Why do you need to write the literature review? A literature review is written before a study commences for basically two reasons:

- to prevent duplication of studies made on a phenomenon thus saving time, money, and effort; and

- to demonstrate the “gap” in knowledge on a given topic thus exactly pinpointing where the new study will be focused.

The literature review reveals how extensively, or how narrowly, the phenomenon has been studied by specialists or experts of the field. It uses secondary information. It serves as a general guide for other researchers as they try to affirm, refute or offer new explanations to a fact or event that they are interested in.

The conduct of research requires a literature review. The review enables you, as a researcher, to get a good grasp of the topic at hand.

Where to Source the Contents of the Literature Review

Visit open access journals.

You must be careful in selecting the literature from websites that will be part of your review because of the preponderance of “scientific” journals that take advantage of unsuspecting researchers looking for a platform to publish their findings in open access journals. To prevent being victimized, evaluate your sources for reliability.

Jeffrey Beal, a librarian at the University of Colorado, took time to list some questionable open-access journals . If you have been invited to publish in these journals or serve as editor or member of the board, think twice.

Browse the site and evaluate the quality of the articles posted. Poor grammar, wrong spelling, poorly formatted articles, or garbled information are tell-tale signs of predatory journals.

It is easy to be misled as everybody can easily access a large body of literature using the internet. You must therefore adopt a prudent attitude in selecting literature from websites that will help you develop a good thesis statement.

As open-access journals become popular sources of scientific literature, a good researcher must develop a keen eye in selecting the wheat from the chaff. Being keen is one of the characteristics of a good researcher .

One of my favorite open-access sites where I can download literature on many topics is www.doaj.org . On this site, there are full papers available for free download. You need to be patient as you browse the site using your keyword. Elsevier also has a list of open access journals here .

There are many other open access journals if you have the time and the patience to do the surfing. Open access journals are the default choice particularly to those who do not have the funds for a personal subscription.

Verify if your library has paid subscriptions to popular scientific journals which offer more choices. This will cut downtime for you to be able to understand current research and establish the state of the art.

Ask a professor for copies of their article collection

One MS student approached me one time asking if I have literature on community-based resource management. Indeed, her inquiry bore fruit as I subscribe to a biannual environmental science journal. I lent her six issues and she was so grateful for the help.

Don’t hesitate to approach someone who might be working on something similar to your line of interest. Almost always, there’s a pile of literature that he or she can share with you so you can quickly browse the topics.

Join sites where scientific articles are shared

One of the growing websites that many scientists join is academia.edu. A colleague reminded me that is a good source of scientific articles because some generous scientists upload and share their articles for everyone to peek into and possibly include in their list of related literature.

I uploaded an article in portable document format (PDF) myself and I noticed high traffic on that single article alone. Now, academia.edu boasts 168,557,587 member academics and researchers.

You may also write those scientists who might be interested in your proposed investigation. There’s a good chance the author will respond to you given the citation potential of their papers. Be grateful by citing the paper when the author is gracious enough to share with you the findings. The methodology part is an excellent guide for your own research.

Visit relevant government offices

A trip to government offices that usually have mini-libraries store information on office programs, projects, and activities plus other informative materials for public use can help you enhance the quality of the information in your study area’s profile. Statistics on demographics, detailed maps, and recent public service initiatives are commonly found in these offices.

Research is meant to improve the quality of human life, and the government is tasked to provide welfare to the general public. Thus, you can orient your research to address issues and problems that were already identified in such government offices.

If your study is about the environment, then the sensible choice is the environment agency of the government. You can help improve on or enhance current environmental policy using identified issues and concerns on the environment as government employees interact directly with local communities. Surely, your research will be appreciated by policymakers.

Replicate yourself

Why do the literature review by yourself when you can engage the help of others — for a fee, of course. I did this when I was conceptualizing my research topic. That happened during the time when the internet boom has just begun and open access journals are not yet available.

I learned that there was an enterprising group of graduate students who offered to do the literature review for a fixed rate. They do all the legwork, i.e., scrounging the libraries and finding relevant materials based on my set of keywords and problem statement.

That service surely saved me a lot of time while I narrow down my research topic using my collection of related literature. The added material strengthened my arguments and/or redefined the direction of my investigation.

Organizing the Literature Review

Write the literature review along with the stated objectives of the study.

There should be a one-to-one correspondence between the objectives of the research paper and the literature review. Tackling the subject bearing the objectives of the research, or guided by the statements of the problem, helps you form a logical central argument in your study.

Prioritize the references

Prioritize your collection of literature according to the most rigorously reviewed publications as follows:

- Scientific articles with international circulation published by reputable journals,

- Books or chapters in books published by publishers of known repute,

- Articles in refereed national journals,

- Papers in national and international conference proceedings or research reports,

- Ph.D. dissertations and Masters theses, and

- Websites and articles in non-refereed journals.

Given the emphasis on gender equality in recent years, you can prioritize scientific papers written by women to strike a balance in perspectives in the pool of literature traditionally dominated by men . Be conscious, too, of making your paper inclusive of different geographies as pointed out by Maas et al. (2021).

Organize your review of literature by themes

Look for keywords that can represent the findings when clumped together. Group similar arguments together and contrast with opposing views. Thereafter, make a synthesis of the discussion and point out the gaps in knowledge or vague areas that are left unresolved.

Things to Bear in Mind Before Writing the Literature Review

Writing a literature review is a tedious task unless you apply a systematic approach to it. But first, you must get back to the very reason why you are writing the literature review to appreciate its role in completing your research paper or thesis.

Since the internet is a great source of information and is nowadays a common destination for researchers who want to access the latest information as quickly as possible, care must be exerted in selecting research papers that will help you build your thesis.

Reinventing the Wheel

Reviewing the literature prevents the duplication of previous work done on the topic identified. Thus, literature review saves money, time, and effort. It prevents the “reinvention of the wheel.” This idiomatic expression means that doing something that others have already done is a waste of time.

Reading a great deal does not mean that you will just read any literature that comes your way. This means that you have read literature that are backed up by evidence, meaning, scientific papers, or articles that are found in peer-reviewed journals or reliable sources. Reliable sources ensure that you have a good foundation in making a thoughtful position embodied in your thesis statement .

Clear Understanding of the Research Topic

A literature review revolves around a central theme – the research topic or research problem. State your research topic clearly to guide the literature review. A good review of literature starts with a good understanding of the research topic.

Writing the research topic in question form facilitates the literature review. The research problem arises from observing a phenomenon that prompts the need for a research investigation.

For example, the disaster response team observed that despite government warnings to evacuate in anticipation of a strong typhoon, many residents opted to stay in their homes despite the threat to their lives and property.

Several questions arise such as:

1. Does ignorance of the government’s warning of the impending danger indicate that people do not trust weather predictions?

2. Do residents value their property more than their lives?

3. Do the residents feel that they will survive the disaster despite its severity? What made them feel that way?

Use of Relevant Keywords in the Search for Related Literature

The three questions clearly state the focus of the review of the literature. One can deduce relevant keywords for online search of related literature. For example, for the first problem statement, you can use the keyword “believability of weather predictions.”

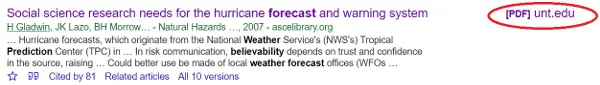

Typing “believability of weather predictions” in Google Scholar returns the following related literature:

The above figure shows that other researchers have conducted studies related to the first problem statement. Two out of ten articles returned relate to the first question. We can say then that the topic is researchable. Figure 1 also shows the following information:

- the title of the study (in large blue fonts);

- the authors with the major author underlined, the date and the publisher (in green);

- a meta description that summarizes the page’s content (three lines of description in black highlighting keywords related to the searched keyword);

- information on article citations (46 and 81 respectively in the two articles); and

- a link to related articles.

Clicking on the title link of the first article, the following abstract comes up:

This study assessed responses to variations of several notable news credibility measures. TV news was evaluated as more credible than newspapers, although its margin of supremacy was a function of researcher operationalizations of the concept.

The study is about news credibility and the influence of the researcher’s method on news credibility. Television news was found more credible than newspapers. But we are not after credibility comparison of television and newspapers. This finding is not the kind of information that we want. So we proceed to the next article about hurricane forecasts and warning systems.

Clicking on the title link of the succeeding article, the abstract appears. Although the article’s focus is on hurricane warnings, you can discern that the article discusses high-priority social science issues. Again, this write-up appears to be still out of the topic.

However, getting back to the meta description and upon closer scrutiny, there is a piece of important information that may be of use. It says, “In risk communication, believability depends on trust and confidence in the source, raising …” (Figure 3). This statement is important information that a researcher can follow through. The article, after all, may be relevant to what we want. We need to secure the article.

We are fortunate that upon checking on the article again, there is a link at the far right that indicates a pdf file (encircled in red) is available for download. After downloading and reading the article, I found out that there are many relevant statements related to the issue of the believability of predictions.

It will now be easy to collect other articles similar to the above article using the same procedure. Identify the relevant article title, read the meta description, and explore the availability of the material. With patience and a little imagination, you can collect the literature that you need for your research.

Landmark Papers: Most Cited

Researchers consider some research publications with high regard. These publications are referred to as landmark papers. Landmark, must-read, papers have become popular among researchers as sensible sources of information. Usually well-known authority figures in the field author these publications.

However, the popularity of a paper does not necessarily mean that the arguments, hypotheses, or theories presented by that author elude correction. Contemporary researchers, armed with new insights from pieces of evidence gathered through meticulous research or experimentation, can debunk the philosophies advanced by an authority figure and render them as myths.

Theories from well-known personalities can always be challenged as new information comes in. For example, Aristotle, one of the greatest intellectual figures of western history, proclaimed that women have fewer teeth than men . Of course, he missed counting the teeth to verify his statement. Until… somebody challenged the idea by just suggesting “Let’s count.” A simple experiment ended the idea from a well-known figure.

Critically evaluate the literature

A critical evaluation of the literature can be more systematic by asking yourself the following questions:

- Has research been done before on the topic that you have identified?

- What are the salient findings of the researchers about your chosen topic?

- How are the findings relevant to your study? Do those findings directly connect to what you have in mind?

- What makes your study unique or different from what has been done before?

- Is there agreement or disagreement in the findings of the researchers?

- Are there vague areas or flaws in the methods or methodology of the reviewed literature?

- How can I fill in the gap in knowledge?

How do you write a literature review?

After you have gathered the necessary literature related to the topic you have chosen to do research on, the next step is to write the literature review. Writing the literature review is quite a challenge, as you will have to rewrite, in your own words to avoid plagiarism, the scientific articles that you have read. The important findings of an article can be described in a paragraph of a few sentences.

The following steps make the review methodical:

Step 1. Rewrite the article to summarize the salient points

What information will you include in the description of other researchers’ work? Essentially, the paragraph should contain the following:

- The author(s) and date when the article was published;

- What the authors did (the method);

- The variables they examined or manipulated;

- A short description of the major findings; and

- A brief explanation of relationships, trends, or differences between variables.

Here’s an example:

Regoniel et al . (2017) examined the adaptation options of stakeholders to typhoons in two coastal communities, one directly exposed to the open sea while the other is buffered from strong winds by islets near the coast. The coastal residents in the community directly exposed to strong typhoons built concrete breakwater structures to mitigate the effects of storm surges and strong waves. On the other hand, the other community opted to reforest the mangroves along the coastline.

Apparently, the intensity of typhoons caused the difference in response to typhoons, one group opted for a quick fix by putting up a breakwater while the other chose mangrove reforestation as a long-term strategy because there is no immediate need to reduce the impact of typhoons.

Step 2. Decide on the arrangement of paragraphs

Which article description should go first?

Some researchers arrange by topic or theme, while others prefer to organize the articles using the set of questions posed in the introduction, specifically, according to problem statements arrangement. The latter appears to be more effective as the issue or concern orients the reader.

The literature review serves as an attempt to answer the questions posed in the early part of the research paper, but of course, it is unable to do so because the review should

- point out the “gap” in knowledge,

- show the insufficiency of current literature to resolve or convincingly explain the phenomenon in question, or

- merely describe what attempts have been made so far to explain the phenomenon.

Step 3. Link the paragraphs

The next step is to link the different paragraphs using introductory statements and ending with concluding sentences. You may add transition paragraphs in between the descriptions of studies to facilitate the flow of ideas.

Step 4. Write your opening and closing paragraphs

At the beginning of the Literature Review section, add a paragraph that explains the content of the whole write-up. The introductory paragraph serves as the reader’s guide on what one expects to read in the review. End with another paragraph that briefly summarizes the shreds of evidence that support the thesis of the research paper .

Writing the literature may be difficult at first, but with careful planning, practice and diligence, you can come up with a good one. Once you’re done with your literature review, more than half of your thesis writing task is already done.

When do you stop writing the literature review?

When do you stop searching the literature? The following tips will help you decide whether to go on searching the literature or not on your research topic.

Stop searching the literature when literature contents are repetitive

As it is common nowadays to use online databases, you may stop searching the literature once the same articles appear even when you vary your keywords on a particular topic. You can be confident that whatever you have missed may not matter that much.

Examples of online databases to explore include the following: Google Scholar, Scopus, Directory of Open Access Journals, ProQuest, African Journals Online, arXiv, BioOne, among others. Wikipedia lists an extensive collection of academic databases for free or via subscription.

My personal experience in using Google Scholar showed relevant articles for my chosen topic in the first 20-30 titles or links. Reading the meta description for each title helps me decide whether to read the abstract or not. The meta description is that snippet of information found just below the title of the article.

Two examples of meta descriptions are given below for the keyword “believability of weather predictions.”. The meta description is computer language for the summary of the contents of a page for the benefit of users and search engines. It is that snippet of information found after the green link or the third line of text in the two examples.

You can exhaust your literature search by looking at the bibliographic entries of articles. That is if you can access the whole paper. Open access articles may be available. While subscription journals are still considered suitable reference materials, open access articles are gaining ground. The European Commission promotes open access publishing gains to better and efficient science as well as innovation.

Point of Saturation of the Literature Review

Familiarity with the research or investigation made by other researchers enables you to understand the issue at hand better. Upon reading a substantial number of research studies, there comes a time when you encounter nothing new. If you have experienced this, you have reached the point of saturation. Thus, you can confidently say that you have read enough scientific papers related to the topic.

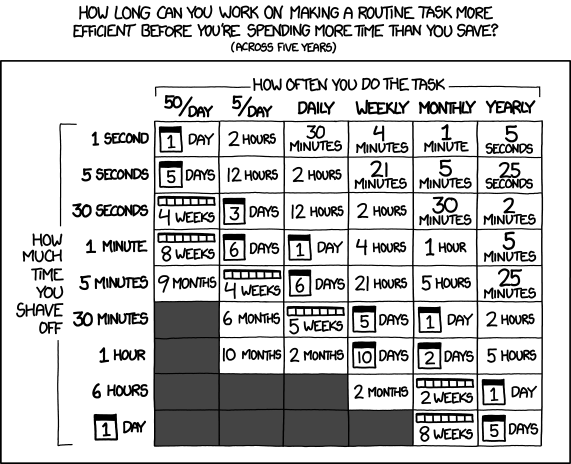

Consider your submission deadline

To be pragmatic about it, you need to deliver the goods within a specified period. If you are given a month or even a few weeks to search the literature, you do not have the luxury of time to write an extensive literature review.

If you are doing your literature review within a semester, then, by all means, keep to that schedule. Your “free time” may be windows of one to two hours of reading in a day as you comply with the other requirements of the course.

It would help if you had adequate time to synthesize the literature. Come up with your conceptual framewor k within a reasonable period. After reading about 20-30 references, you may likely have already conceptualized something significant. Keep to your deadline. Planning a strategy on how to do things on time can help you achieve your task.

Finding a meta-analysis, for example, can save you a lot of time. A meta-analysis systematically assesses the results of previous research to derive conclusions about that body of research. In effect, it brings relevant literature together in one study.

Thus, a synthesis facilitates literature search. Just update or enhance the composition to come up with your conclusions or synthesis.

The gap in knowledge has been found

Stop searching the literature if you have found a knowledge gap . A research gap pertains to unexplored areas of study. It takes a while to discern such a gap, so you need to be patient in reading the literature and note down the significant findings.

Knowing when to stop searching the literature depends in part on your familiarity with the topic at hand. Hence, it pays to study something where you become more familiar, as you go through your academic pursuit. That is the mark of being a specialist in your field.

It all boils down to the study’s objectives and having a clear purpose, the time you have available, and the guidance of your experienced adviser familiar with the subject.

In my experience, the limiting factor is time, as you can’t afford to capture everything written about the subject. Find the most recent landmark or seminal works about your specific topic whenever available. That will give you more confidence that indeed you have read the most relevant references.

Professor Liesbet van Zoonen, of Erasmus University, gives some more tips on when to stop writing the literature review in the following video. Grab a cup of coffee, relax and listen intently to what she is saying.

Concluding Statements

In conclusion, the literature review sheds light on what has been done so far about the research topic. It reveals “gaps” that warrant further investigation. Good research practice presents this gap in knowledge in the introduction of the study. Statement of objectives or problem statements to address that gap follow. Hence, a follow-up study produces new information.

There you go. I hope you both learned and enjoyed reading this article. Keep safe and be confident in writing your literature review in the safety of your home.

Ashton, W. (2015). Writing a Short Literature Review. Retrieved on January 6, 2015 from http://www.ithacalibrary.com/sp/assets/users/_lchabot/lit_rev_eg.pdf

Maas, B., Pakeman, R. J., Godet, L., Smith, L., Devictor, V., & Primack, R. (2021). Women and Global South strikingly underrepresented among top-publishing ecologists. Conservation Letters, e12797.

Regoniel, P. A., Macasaet, M. T. U., & Mendoza, N. I. (2017). Economic analysis of adaptation options in Honda Bay, Puerto Princesa City, Philippines. EEPSEA Research Report , (2017-RR3).

©2021 October 30 P. A. Regoniel

Related Posts

10 research paper presentation tips, five tips for research paper presentation, the importance of time management and exercise, about the author, patrick regoniel.

Dr. Regoniel served as consultant to various environmental research and development projects covering issues and concerns on climate change, coral reef resources and management, economic valuation of environmental and natural resources, mining, and waste management and pollution. He has extensive experience on applied statistics, systems modelling and analysis, an avid practitioner of LaTeX, and a multidisciplinary web developer. He leverages pioneering AI-powered content creation tools to produce unique and comprehensive articles in this website.

🚀 Work With Us

Private Coaching

Language Editing

Qualitative Coding

✨ Free Resources

Templates & Tools

Short Courses

Articles & Videos

🎙️ PODCAST: Ace The Literature Review

4 Time-Saving Tips To Fast-Track Your Literature Review

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) and Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD) | Feb 2024

Writing a literature review can be a daunting task for many students, but fear not! In this episode of the Grad Coach Podcast, we unveil four “cheat codes” that will help you fast-track your literature review process and ensure you stay on the right track.

Episode Summary

————————————-

#1: Use Your Research Aims and Questions To Guide Your Search

When embarking on your literature search, use your research aims and questions as a compass to guide you. By inputting the keywords from your research questions into databases like Google Scholar, JSTOR, or your university’s academic repository, you can refine your search results to align closely with your research goals. This strategic approach not only saves time but also ensures that the literature you find is directly relevant to your study.

#2: Plan Out Your Chapter Structure in Advance

Before diving into writing your literature review, sketch out a loose structure outlining the introduction, main topics, and conclusion. By aligning this structure with your research questions, you can streamline your writing process and maintain focus throughout. Having a roadmap in place helps prevent digressions and ensures a cohesive flow in your review.

#3: Aim for Analytical Writing over Descriptive Writing

Distinguish between descriptive writing, which presents facts, and analytical writing, which delves into the significance and implications of these facts. When analysing sources, ask yourself the “so what” question to uncover the deeper meaning behind the information. By critically evaluating the data in relation to your research aims, you can elevate your literature review to a more insightful and impactful level.

#4: Embrace “Quote Sandwiches”

When incorporating quotes from sources, remember to use quote sandwiches. Introduce the quote with contextual information, insert the quote itself, and follow up with an explanatory sentence that links back to your research. This method not only enhances the readability of your writing but also demonstrates a deeper understanding of the cited material.

If you found these tips valuable, don’t forget to check out our free literature review template .

Need a helping hand?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

* E-mail: [email protected]

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Collection date 2013 Jul.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly credited.

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

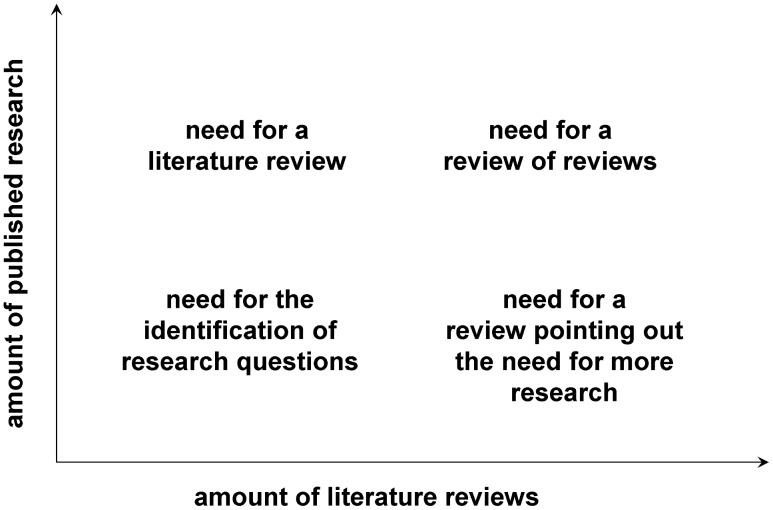

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

Figure 1. A conceptual diagram of the need for different types of literature reviews depending on the amount of published research papers and literature reviews.

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

be thorough,

use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

the major achievements in the reviewed field,

the main areas of debate, and

the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

- 1. Rapple C (2011) The role of the critical review article in alleviating information overload. Annual Reviews White Paper. Available: http://www.annualreviews.org/userimages/ContentEditor/1300384004941/Annual_Reviews_WhitePaper_Web_2011.pdf . Accessed May 2013.

- 2. Pautasso M (2010) Worsening file-drawer problem in the abstracts of natural, medical and social science databases. Scientometrics 85: 193–202 doi: 10.1007/s11192-010-0233-5 [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Erren TC, Cullen P, Erren M (2009) How to surf today's information tsunami: on the craft of effective reading. Med Hypotheses 73: 278–279 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.05.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Hampton SE, Parker JN (2011) Collaboration and productivity in scientific synthesis. Bioscience 61: 900–910 doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.11.9 [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Ketcham CM, Crawford JM (2007) The impact of review articles. Lab Invest 87: 1174–1185 doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700688 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Boote DN, Beile P (2005) Scholars before researchers: on the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educ Res 34: 3–15 doi: 10.3102/0013189X034006003 [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Budgen D, Brereton P (2006) Performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Proc 28th Int Conf Software Engineering, ACM New York, NY, USA, pp. 1051–1052. doi: 10.1145/1134285.1134500 .

- 8. Maier HR (2013) What constitutes a good literature review and why does its quality matter? Environ Model Softw 43: 3–4 doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.02.004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Sutherland WJ, Fleishman E, Mascia MB, Pretty J, Rudd MA (2011) Methods for collaboratively identifying research priorities and emerging issues in science and policy. Methods Ecol Evol 2: 238–247 doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00083.x [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Maggio LA, Tannery NH, Kanter SL (2011) Reproducibility of literature search reporting in medical education reviews. Acad Med 86: 1049–1054 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822221e7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Torraco RJ (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Human Res Develop Rev 4: 356–367 doi: 10.1177/1534484305278283 [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Khoo CSG, Na JC, Jaidka K (2011) Analysis of the macro-level discourse structure of literature reviews. Online Info Rev 35: 255–271 doi: 10.1108/14684521111128032 [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Rosenfeld RM (1996) How to systematically review the medical literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 115: 53–63 doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70137-7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Cook DA, West CP (2012) Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Med Educ 46: 943–952 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04328.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Dijkers M (2009) The Task Force on Systematic Reviews and Guidelines (2009) The value of “traditional” reviews in the era of systematic reviewing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 88: 423–430 doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31819c59c6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Eco U (1977) Come si fa una tesi di laurea. Milan: Bompiani.

- 17. Hart C (1998) Doing a literature review: releasing the social science research imagination. London: SAGE.

- 18. Wagner CS, Roessner JD, Bobb K, Klein JT, Boyack KW, et al. (2011) Approaches to understanding and measuring interdisciplinary scientific research (IDR): a review of the literature. J Informetr 5: 14–26 doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2010.06.004 [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Carnwell R, Daly W (2001) Strategies for the construction of a critical review of the literature. Nurse Educ Pract 1: 57–63 doi: 10.1054/nepr.2001.0008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Roberts PD, Stewart GB, Pullin AS (2006) Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biol Conserv 132: 409–423 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2006.04.034 [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Ridley D (2008) The literature review: a step-by-step guide for students. London: SAGE.

- 22. Kelleher C, Wagener T (2011) Ten guidelines for effective data visualization in scientific publications. Environ Model Softw 26: 822–827 doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.12.006 [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Oxman AD, Guyatt GH (1988) Guidelines for reading literature reviews. CMAJ 138: 697–703. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. May RM (2011) Science as organized scepticism. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 369: 4685–4689 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0177 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]