Informative Speech Thesis Statement

Informative speech generator.

Unlock the power of effective communication with informative speech thesis statement examples. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the art of crafting compelling thesis statements for informative speeches. From unraveling the intricacies of informative speech thesis statements to providing step-by-step writing strategies, you’ll gain valuable insights into captivating your audience’s attention and delivering informative speeches that leave a lasting impact. Elevate your speaking prowess with expert tips tailored to engaging and enlightening your listeners.

What is an Informative Speech Thesis Statement? – Definition

An informative speech thesis statement is a concise and focused sentence that encapsulates the main idea or central message of an informative speech. It serves as a roadmap for the audience, providing them with a clear preview of the topics, concepts, or information that will be presented in the speech. The informative speech thesis statement helps the audience understand the purpose of the speech and what they can expect to learn or gain from listening.

What is an Example of Informative Speech Thesis Statement?

Example: “In this informative speech, I will explore the history, cultural significance, and health benefits of traditional herbal remedies used by indigenous communities around the world.”

In this example, the informative speech thesis statement clearly outlines the main topics that will be covered in the speech. It indicates that the speech will delve into the history, cultural importance, and positive health effects of traditional herbal remedies within indigenous cultures globally. This thesis statement provides a roadmap for the audience, giving them a glimpse of the informative content that will follow in the speech. In addition, you should review our thesis statement for personal essay .

100 Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples

Size: 173 KB

- Today, we’ll explore the mysterious world of the deep sea and the creatures that inhabit it.

- The history of chocolate reveals a complex journey from Mayan rituals to modern day luxury.

- Understanding the basics of solar energy can lead us to sustainable solutions for the future.

- The Great Wall of China represents centuries of historical evolution, defense strategies, and cultural significance.

- Let’s delve into the intricate world of bee communication and the role of pheromones.

- The human brain’s plasticity offers insights into learning, memory, and recovery.

- The art of origami goes beyond paper folding, reflecting Japanese traditions and philosophical insights.

- Mount Everest’s geological formation, history, and climbing challenges are both captivating and daunting.

- Sleep is a complex process that affects our mental, emotional, and physical health in surprising ways.

- Leonardo da Vinci’s inventions showcase the genius of a Renaissance man.

- The process of wine-making, from grape to glass, combines art and science.

- By understanding the different waves of feminism, we can appreciate the evolution of gender rights.

- The history of the Olympics traces the evolution of human athleticism and global unity.

- Artificial intelligence’s rise and implications touch every facet of our modern lives.

- Delve into the mysterious culture and rituals of the Maasai tribe in East Africa.

- The Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, is a natural wonder driven by Earth’s magnetism.

- The evolution of the internet has transformed global communication, commerce, and culture.

- The Silk Road was more than a trade route; it was a bridge between cultures and epochs.

- The health benefits of meditation extend beyond relaxation, influencing brain structure and function.

- Exploring the dynamics of black holes uncovers the universe’s enigmatic phenomena.

- The ancient pyramids of Egypt tell tales of pharaohs, engineers, and a civilization ahead of its time.

- Yoga, beyond flexibility, promotes holistic health and spiritual growth.

- The migration patterns of monarch butterflies are one of nature’s most astonishing journeys.

- Unpacking the ethical implications of cloning gives insights into the future of biotechnology.

- The life cycle of a star reveals the universe’s beauty, complexity, and constant change.

- From farm to cup, the journey of coffee beans impacts economies, cultures, and your morning ritual.

- The Renaissance era: an explosion of art, science, and thought that shaped the modern world.

- The complexities of the human immune system defend us against microscopic invaders daily.

- Antarctica’s ecosystem is a fragile balance of life, adapting to the planet’s harshest conditions.

- The Titanic’s tragic voyage remains a lesson in hubris, safety, and fate.

- Let’s understand the intricacies of quantum mechanics and its revolution in modern physics.

- Delve into the world of paleontology and the mysteries of dinosaur existence.

- Sign languages around the world are rich, diverse modes of communication beyond spoken words.

- The world of dreams: decoding symbols, understanding stages, and their impact on our psyche.

- The Wright brothers’ journey was a testament to innovation, persistence, and the human spirit.

- The evolution of musical genres reflects societal changes, technological advancements, and cultural blends.

- Samurai warriors embody the ethos, discipline, and martial traditions of feudal Japan.

- The three states of matter offer a basic understanding of the universe’s physical essence.

- The Hubble Space Telescope has revolutionized our perception of the universe and our place within it.

- Journey through the rich tapestry of African tribal cultures, traditions, and histories.

- The concept of time travel, while popular in fiction, presents scientific and philosophical challenges.

- Explore the world of forensic science and its pivotal role in modern criminal justice.

- Delve into the world of cryptocurrencies, their workings, and their potential to redefine finance.

- The linguistic diversity of the Indian subcontinent showcases a mosaic of cultures, histories, and beliefs.

- The process of photosynthesis is nature’s way of converting light into life.

- The mysteries of the Bermuda Triangle have intrigued scientists, historians, and travelers alike.

- Uncover the importance and workings of vaccines in combating infectious diseases.

- The Eiffel Tower is more than an icon; it’s a testament to engineering and cultural symbolism.

- Delving into the myths, facts, and history of the majestic white wolves of the Arctic.

- The cultural, economic, and culinary significance of rice in global civilizations.

- Discover the beauty, function, and preservation of coral reefs, the oceans’ rainforests.

- The enigma of Stonehenge reflects ancient engineering, astronomical knowledge, and cultural rituals.

- Human memory is a complex interplay of neurons, experiences, and emotions.

- The history of jazz music: its roots, evolution, and impact on modern music genres.

- The incredible world of bioluminescence in deep-sea creatures.

- The philosophy and practices of Buddhism offer a path to enlightenment and inner peace.

- The Big Bang Theory unravels the universe’s origin, expansion, and eventual fate.

- Examine the rich history, culture, and significance of Native American tribes.

- The formation and importance of wetlands in maintaining global ecological balance.

- The metamorphosis process in butterflies: a dance of genes, hormones, and time.

- Delve into the wonders of the human genome and the secrets it holds about our evolution.

- The history and future of space exploration: from the moon landings to Mars missions.

- Discover the dynamic world of volcanoes, their formation, eruption, and influence on ecosystems.

- The French Revolution: its causes, timeline, and lasting impacts on global politics.

- Breaking down the science and art behind architectural marvels across history.

- The multifaceted world of the Amazon rainforest: its biodiversity, tribes, and conservation challenges.

- The principles and practices of sustainable farming in modern agriculture.

- Decoding the mysteries of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization.

- The art of bonsai: a journey of patience, aesthetics, and nature’s miniaturization.

- The Second World War: its origins, major events, and lasting global implications.

- The water cycle: nature’s way of sustaining life on Earth.

- Understanding autism: its spectrum, challenges, and societal implications.

- The cultural, historical, and spiritual significance of the holy city of Jerusalem.

- The physics and thrill of skydiving: conquering gravity and fear.

- The impact of the printing press on literature, religion, and the dissemination of knowledge.

- Delve into the intriguing world of espionage: its history, techniques, and impact on geopolitics.

- The cinematic evolution of Hollywood: from silent films to digital masterpieces.

- The profound impact of the Harlem Renaissance on art, literature, and black consciousness.

- The fascinating science behind earthquakes and our quest to predict them.

- The challenges, resilience, and beauty of life in the world’s deserts.

- The role and significance of the United Nations in global peace and diplomacy.

- The fashion revolutions of the 20th century and their socio-cultural impacts.

- Journey through the intricate and diverse world of spiders.

- The principles and history of the art of storytelling across civilizations.

- The enigma and allure of the Mona Lisa: beyond the smile and into da Vinci’s world.

- The magic of magnetism: its principles, applications, and mysteries.

- The impact of social media on society: communication, psychology, and privacy concerns.

- The mysteries and significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls in biblical research.

- The innovations and challenges of deep-sea exploration.

- Explore the evolution, beauty, and significance of Japanese tea ceremonies.

- The majestic world of eagles: species, habitats, and their role in ecosystems.

- The cultural and historical significance of ancient Greek theater.

- Dive into the art and techniques of cinematography in filmmaking.

- The complex history and geopolitics of the Panama Canal.

- The practice and significance of animal migration across species and ecosystems.

- The legacy and lessons of the Roman Empire.

- The beauty, challenges, and adaptations of alpine flora and fauna.

- The history, techniques, and significance of mural painting across cultures.

- The science and wonder of rainbows: from mythologies to optics.

- Discover the significance and celebrations of Diwali, the festival of lights.

Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples for Introduction

An introductory informative speech thesis statement sets the stage, creating intrigue or establishing the context for the topic that follows. It lays the groundwork for what listeners can anticipate.

- Let’s embark on a journey through the ages, exploring the timeless allure of ancient civilizations.

- As we unravel the secrets of the universe, we begin with its most mysterious element: dark matter.

- Today, let’s understand the fabric of our global economy and the threads that weave it together.

- Venturing into the digital realm, we’ll discover the evolution and impact of social media on human connections.

- Set sail with me to explore the enigmatic world of lost cities submerged beneath the seas.

- Journeying back in time, we delve into the age of chivalry and the knights of old.

- Let us embark on an odyssey into the intricate realm of modern art and its diverse interpretations.

- Today, we set foot in the mesmerizing world of optical illusions and the psychology behind them.

- Navigating through the labyrinth of the human mind, we begin with dreams and their interpretations.

- As we chart our course today, let’s explore the unsung heroes behind history’s greatest discoveries.

Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples for Graduation

Graduation speeches are pivotal moments, focusing on accomplishments, transition, and the journey ahead. A concise thesis statement should resonate with the gravity of the milestone.

- Today, we celebrate not just the culmination of years of hard work but the dawn of new beginnings.

- Graduation is a testament to perseverance, growth, and the dreams we dared to chase.

- We stand on the threshold of a new era, armed with knowledge, experiences, and ambitions.

- Together, we’ve climbed mountains of challenges, and today, we pause to admire the view.

- This graduation isn’t an endpoint but a launching pad for dreams yet to be realized.

- Through shared challenges and achievements, we’ve woven a tapestry of memories and aspirations.

- Today, as we close this chapter, we eagerly await the stories we’re destined to write.

- Graduation is a reflection of past endeavors and the beacon guiding our future journeys.

- As we don the cap and gown, we embrace the responsibilities and promises of tomorrow.

- This ceremony is a tribute to our resilience, aspirations, and the legacy we’re beginning to build.

Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples For Autism

Autism speeches inform and spread awareness. The thesis should be insightful, compassionate, and devoid of any stereotypes.

- Autism, in its spectrum, paints a vivid tapestry of diverse experiences and unique strengths.

- Delving into autism, we discover not just challenges but unparalleled potential and perspectives.

- Unpacking the world of autism offers a glimpse into diverse minds shaping our world uniquely.

- Autism is not a limitation but a different lens through which the world is perceived.

- Through understanding autism, we pave the way for inclusivity, appreciation, and holistic growth.

- Autism, in its essence, challenges societal norms, urging us to redefine success and potential.

- Embracing the autistic community is embracing diversity, creativity, and the myriad ways of being human.

- Navigating the realm of autism, we find tales of resilience, innovation, and boundless spirit.

- Autism stands as a testament to human neurodiversity and the endless forms of intelligence.

- In the heart of autism lies the profound message of acceptance, understanding, and unbridled potential.

Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples on Depression

When discussing depression, the thesis should be sensitive, informed, and aimed at eliminating stigma while spreading awareness.

- Depression, often silent, is a profound emotional experience that impacts countless lives globally.

- Delving into the depths of depression, we uncover its nuances, challenges, and paths to healing.

- Today, we shine a light on the shadows of depression, fostering understanding and empathy.

- Depression, beyond just a mood, is a complex interplay of biology, environment, and experiences.

- Recognizing and addressing depression is pivotal to building a compassionate and resilient society.

- In understanding depression, we equip ourselves with tools for empathy, intervention, and support.

- Depression, while daunting, also presents stories of strength, recovery, and hope.

- Through the lens of depression, we see the urgent need for mental health advocacy and education.

- Navigating the intricate world of depression helps dispel myths and foster genuine understanding.

- As we unravel the fabric of depression, we realize its universality and the importance of collective support.

Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples on Life

Life, in its vastness, offers endless topics. A thesis on life should be profound, insightful, and universally resonant.

- Life, in its ebb and flow, presents a mosaic of experiences, challenges, and joys.

- Delving into the journey of life, we find lessons in the most unexpected moments.

- Life, with its unpredictable twists, teaches us resilience, adaptability, and the value of time.

- Through life’s lens, we appreciate the transient beauty of moments, relationships, and dreams.

- Life’s tapestry is woven with threads of memories, decisions, and the pursuit of purpose.

- Navigating the terrain of life, we encounter peaks of joy and valleys of introspection.

- Life’s rhythm is a dance of challenges met, lessons learned, and love discovered.

- Embracing life means acknowledging its imperfections, uncertainties, and boundless potentials.

- Life is a rich canvas, painted with choices, experiences, and the colors of emotions.

- In the vast expanse of life, we find the significance of connections, growth, and self-awareness.

Informative Speech Thesis Statement Examples Conclusion

Conclusion thesis statements wrap up the essence of the speech, leaving listeners with poignant thoughts or a call to action.

- As we journeyed through the annals of history, we’re reminded of the footprints we’re destined to leave.

- Having delved deep into the human psyche, we come away enlightened, empowered, and introspective.

- As our exploration concludes, let’s carry forward the knowledge, empathy, and drive to make a difference.

- Wrapping up our journey, we realize that every end is but a new beginning in disguise.

- As we draw the curtains, the lessons imbibed urge us to reflect, act, and evolve.

- In conclusion, the tapestry we’ve woven today serves as a testament to our collective potential.

- As our discourse comes to an end, let’s pledge to be torchbearers of change, understanding, and progress.

- Concluding today’s journey, we’re left with insights, questions, and a renewed sense of purpose.

- As we wrap up, the stories shared serve as beacons, illuminating our paths and choices.

- In the final note, let’s carry the essence of today’s exploration, making it a catalyst for growth and understanding.

What is a good thesis statement for an informative essay?

A good thesis statement for an informative essay is a clear, concise declaration that presents the main point or argument of your essay. It informs the reader about the specific topic you will discuss without offering a personal opinion or taking a stance. The ideal thesis statement is:

- Specific: It should narrow down the subject so readers understand the essay’s scope.

- Arguable: Though it doesn’t express an opinion, it should still be something that might be disputed or clarified.

- Clear: It should be easily understandable without any ambiguity.

- Focused: The thesis should relate directly to the topic, ensuring it doesn’t stray into irrelevant areas.

- Brief: While it should encapsulate your main point, it shouldn’t be excessively long.

Example: “The process of photosynthesis in plants is crucial for converting carbon dioxide into oxygen, a transformation that sustains most life forms on Earth.”

Does an informative speech need a thesis?

Yes, an informative speech does need a thesis. The thesis acts as a compass for your audience, providing them with a clear understanding of what they will learn or gain from your speech. It sets the tone, focuses the content, and provides a roadmap for listeners to follow. An informative speech thesis helps the audience:

- Understand the Purpose: It clearly states what the speech will cover.

- Anticipate Content: It sets expectations for the type of information they will receive.

- Stay Engaged: By knowing the direction, listeners can follow along more easily and attentively.

- Retain Information: With a clear foundation laid by the thesis, the audience can more easily remember key takeaways.

How do you write an Informative speech thesis statement? – Step by Step Guide

Crafting a strong and effective specific thesis statement for an informative speech is vital to convey the essence of your message clearly. Here’s a comprehensive step-by-step guide to help you through the process:

- Select a Suitable Topic: Start with a subject that is engaging and you’re knowledgeable about. This will give your thesis authenticity and enthusiasm.

- Refine Your Topic: A broad subject can be overwhelming for both the speaker and the audience. Narrow it down to a specific aspect or angle that you want to focus on.

- Conduct Preliminary Research: Even if you’re familiar with the subject, conduct some research to ensure you have updated and factual information. This will give your thesis credibility.

- Determine the Main Points: From your research and knowledge, deduce the primary points or messages you wish to convey to your audience.

- Formulate a Draft Thesis: Using your main points, write a draft of your thesis statement. This doesn’t have to be perfect; it’s just a starting point.

- Keep it Clear and Concise: Your thesis should be easily understandable. Avoid jargon and complex words unless they are crucial and you plan to explain them during your speech.

- Ensure Objectivity: An informative thesis aims to educate, not to persuade. Keep it neutral and avoid any personal bias.

- Test for Specificity: Your thesis should be specific enough to give your audience a clear idea of what to expect, but broad enough to encompass the main idea of your speech.

- Seek Feedback: Share your draft thesis with friends, colleagues, or mentors. Their perspectives might offer valuable insights or point out aspects you hadn’t considered.

- Revise and Refine: Based on feedback and further reflection, refine your thesis. Ensure it’s concise, specific, and clearly conveys the main idea of your speech.

- Practice it Aloud: Say your thesis statement out loud a few times. This helps you ensure it flows well and can be easily understood when spoken.

- Align with Content: As you develop the content of your speech, revisit your thesis to ensure it remains consistent with the information you’re presenting. Adjust if necessary.

- Finalize: Once you’re satisfied, finalize your thesis statement. It should be a strong and clear representation of what your audience can expect from your speech.

Remember, your thesis is the foundation of your informative speech. It sets the stage for everything that follows, so taking the time to craft it meticulously is crucial for the effectiveness of your speech.

Tips for Writing an Informative Speech Thesis Statement

- Stay Objective: Avoid personal biases. Your goal is to inform, not persuade.

- Be Specific: General statements can disengage your audience. Specificity grabs attention.

- Limit Your Scope: Don’t try to cover too much. Stick to what’s essential to avoid overwhelming your audience.

- Prioritize Clarity: Use simple, direct language. Avoid jargon unless it’s pertinent and you plan to explain it.

- Test It Out: Before finalizing, say your thesis out loud. This will help identify any awkward phrasings.

- Stay Relevant: Make sure your thesis relates directly to the rest of your speech.

- Avoid Questions: Your thesis should be a statement, not a question.

- Revise as Needed: As you flesh out your speech, revisit your thesis to ensure it still aligns.

- Stay Consistent: The tone and style of your thesis should match the rest of your speech.

- Seek Inspiration: Listen to other informative speeches or read essays to see how experts craft their thesis statements.

Remember, your thesis statement is the anchor of your speech. Invest time in crafting one that is clear, compelling, and informative. You should also take a look at our final thesis statement .

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Create an Informative Speech Thesis Statement on the history of the internet

Write an Informative Speech Thesis Statement for a talk on the evolution of human rights

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1. Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

- An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

- An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text that does not fall under these three categories (e.g., a narrative), a thesis statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

The paper that follows should:

- Explain the analysis of the college admission process

- Explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

- Explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with peers

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

- Present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue community projects before entering college

14 Crafting a Thesis Statement

Learning Objectives

- Craft a thesis statement that is clear, concise, and declarative.

- Narrow your topic based on your thesis statement and consider the ways that your main points will support the thesis.

Crafting a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know, clearly and concisely, what you are going to talk about. A strong thesis statement will allow your reader to understand the central message of your speech. You will want to be as specific as possible. A thesis statement for informative speaking should be a declarative statement that is clear and concise; it will tell the audience what to expect in your speech. For persuasive speaking, a thesis statement should have a narrow focus and should be arguable, there must be an argument to explore within the speech. The exploration piece will come with research, but we will discuss that in the main points. For now, you will need to consider your specific purpose and how this relates directly to what you want to tell this audience. Remember, no matter if your general purpose is to inform or persuade, your thesis will be a declarative statement that reflects your purpose.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech.

Once you have chosen your topic and determined your purpose, you will need to make sure your topic is narrow. One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to seven-minute speech. While five to seven minutes may sound like a long time for new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

Is your speech topic a broad overgeneralization of a topic?

Overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

Is your speech’s topic one clear topic or multiple topics?

A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and Women’s Equal Rights Amendment should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: Ratifying the Women’s Equal Rights Amendment as equal citizens under the United States law would protect women by requiring state and federal law to engage in equitable freedoms among the sexes.

Does the topic have direction?

If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good public speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Declarative Sentence

You wrote your general and specific purpose. Use this information to guide your thesis statement. If you wrote a clear purpose, it will be easy to turn this into a declarative statement.

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: To inform my audience about the lyricism of former President Barack Obama’s presentation skills.

Your thesis statement needs to be a declarative statement. This means it needs to actually state something. If a speaker says, “I am going to talk to you about the effects of social media,” this tells you nothing about the speech content. Are the effects positive? Are they negative? Are they both? We don’t know. This sentence is an announcement, not a thesis statement. A declarative statement clearly states the message of your speech.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Or you could state, “Socal media has both positive and negative effects on users.”

Adding your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement, we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin demonstrates exceptional use of rhetorical strategies.

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

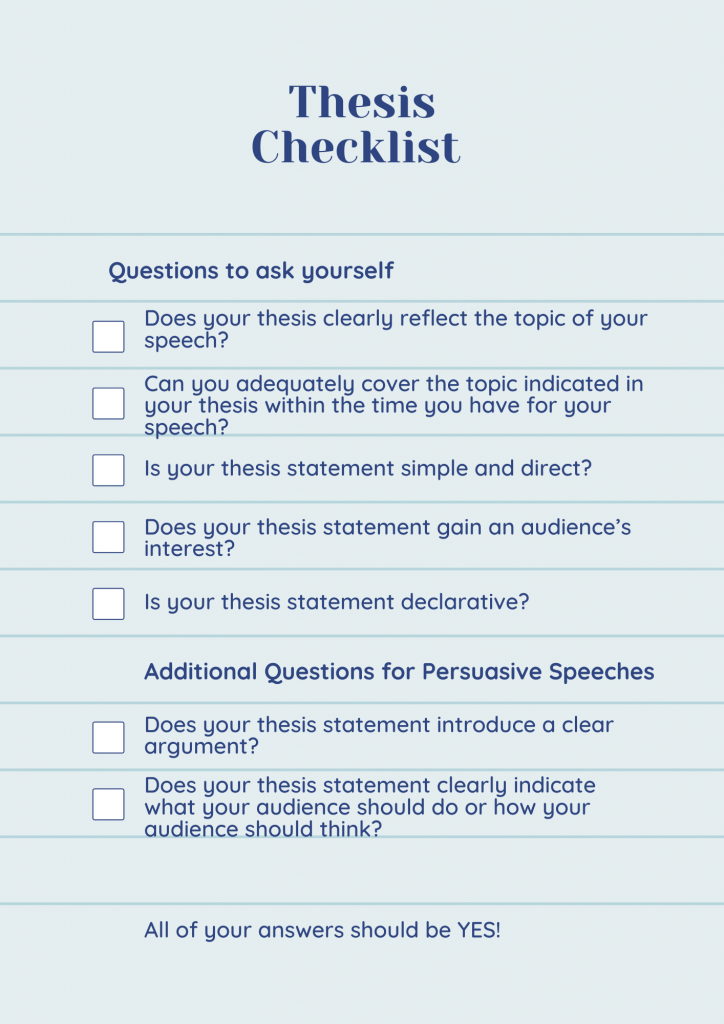

Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown below.

Preview of Speech

The preview, as stated in the introduction portion of our readings, reminds us that we will need to let the audience know what the main points in our speech will be. You will want to follow the thesis with the preview of your speech. Your preview will allow the audience to follow your main points in a sequential manner. Spoiler alert: The preview when stated out loud will remind you of main point 1, main point 2, and main point 3 (etc. if you have more or less main points). It is a built in memory card!

For Future Reference | How to organize this in an outline |

Introduction

Attention Getter: Background information: Credibility: Thesis: Preview:

Key Takeaways

Introductions are foundational to an effective public speech.

- A thesis statement is instrumental to a speech that is well-developed and supported.

- Be sure that you are spending enough time brainstorming strong attention getters and considering your audience’s goal(s) for the introduction.

- A strong thesis will allow you to follow a roadmap throughout the rest of your speech: it is worth spending the extra time to ensure you have a strong thesis statement.

Stand up, Speak out by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.3 Putting It Together: Steps to Complete Your Introduction

Learning objectives.

- Clearly identify why an audience should listen to a speaker.

- Discuss how you can build your credibility during a speech.

- Understand how to write a clear thesis statement.

- Design an effective preview of your speech’s content for your audience.

Erin Brown-John – puzzle – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Once you have captured your audience’s attention, it’s important to make the rest of your introduction interesting, and use it to lay out the rest of the speech. In this section, we are going to explore the five remaining parts of an effective introduction: linking to your topic, reasons to listen, stating credibility, thesis statement, and preview.

Link to Topic

After the attention-getter, the second major part of an introduction is called the link to topic. The link to topic is the shortest part of an introduction and occurs when a speaker demonstrates how an attention-getting device relates to the topic of a speech. Often the attention-getter and the link to topic are very clear. For example, if you look at the attention-getting device example under historical reference above, you’ll see that the first sentence brings up the history of the Vietnam War and then shows us how that war can help us understand the Iraq War. In this case, the attention-getter clearly flows directly to the topic. However, some attention-getters need further explanation to get to the topic of the speech. For example, both of the anecdote examples (the girl falling into the manhole while texting and the boy and the filberts) need further explanation to connect clearly to the speech topic (i.e., problems of multitasking in today’s society).

Let’s look at the first anecdote example to demonstrate how we could go from the attention-getter to the topic.

In July 2009, a high school girl named Alexa Longueira was walking along a main boulevard near her home on Staten Island, New York, typing in a message on her cell phone. Not paying attention to the world around her, she took a step and fell right into an open manhole. This anecdote illustrates the problem that many people are facing in today’s world. We are so wired into our technology that we forget to see what’s going on around us—like a big hole in front of us.

In this example, the third sentence here explains that the attention-getter was an anecdote that illustrates a real issue. The fourth sentence then introduces the actual topic of the speech.

Let’s now examine how we can make the transition from the parable or fable attention-getter to the topic:

The ancient Greek writer Aesop told a fable about a boy who put his hand into a pitcher of filberts. The boy grabbed as many of the delicious nuts as he possibly could. But when he tried to pull them out, his hand wouldn’t fit through the neck of the pitcher because he was grasping so many filberts. Instead of dropping some of them so that his hand would fit, he burst into tears and cried about his predicament. The moral of the story? “Don’t try to do too much at once.” In today’s world, many of us are us are just like the boy putting his hand into the pitcher. We are constantly trying to grab so much or do so much that it prevents us from accomplishing our goals. I would like to show you three simple techniques to manage your time so that you don’t try to pull too many filberts from your pitcher.

In this example, we added three new sentences to the attention-getter to connect it to the speech topic.

Reasons to Listen

Once you have linked an attention-getter to the topic of your speech, you need to explain to your audience why your topic is important. We call this the “why should I care?” part of your speech because it tells your audience why the topic is directly important to them. Sometimes you can include the significance of your topic in the same sentence as your link to the topic, but other times you may need to spell out in one or two sentences why your specific topic is important.

People in today’s world are very busy, and they do not like their time wasted. Nothing is worse than having to sit through a speech that has nothing to do with you. Imagine sitting through a speech about a new software package you don’t own and you will never hear of again. How would you react to the speaker? Most of us would be pretty annoyed at having had our time wasted in this way. Obviously, this particular speaker didn’t do a great job of analyzing her or his audience if the audience isn’t going to use the software package—but even when speaking on a topic that is highly relevant to the audience, speakers often totally forget to explain how and why it is important.

Appearing Credible

The next part of a speech is not so much a specific “part” as an important characteristic that needs to be pervasive throughout your introduction and your entire speech. As a speaker, you want to be seen as credible (competent, trustworthy, and caring/having goodwill). As mentioned earlier in this chapter, credibility is ultimately a perception that is made by your audience. While your audience determines whether they perceive you as competent, trustworthy, and caring/having goodwill, there are some strategies you can employ to make yourself appear more credible.

First, to make yourself appear competent, you can either clearly explain to your audience why you are competent about a given subject or demonstrate your competence by showing that you have thoroughly researched a topic by including relevant references within your introduction. The first method of demonstrating competence—saying it directly—is only effective if you are actually a competent person on a given subject. If you are an undergraduate student and you are delivering a speech about the importance of string theory in physics, unless you are a prodigy of some kind, you are probably not a recognized expert on the subject. Conversely, if your number one hobby in life is collecting memorabilia about the Three Stooges, then you may be an expert about the Three Stooges. However, you would need to explain to your audience your passion for collecting Three Stooges memorabilia and how this has made you an expert on the topic.

If, on the other hand, you are not actually a recognized expert on a topic, you need to demonstrate that you have done your homework to become more knowledgeable than your audience about your topic. The easiest way to demonstrate your competence is through the use of appropriate references from leading thinkers and researchers on your topic. When you demonstrate to your audience that you have done your homework, they are more likely to view you as competent.

The second characteristic of credibility, trustworthiness, is a little more complicated than competence, for it ultimately relies on audience perceptions. One way to increase the likelihood that a speaker will be perceived as trustworthy is to use reputable sources. If you’re quoting Dr. John Smith, you need to explain who Dr. John Smith is so your audience will see the quotation as being more trustworthy. As speakers we can easily manipulate our sources into appearing more credible than they actually are, which would be unethical. When you are honest about your sources with your audience, they will trust you and your information more so than when you are ambiguous. The worst thing you can do is to out-and-out lie about information during your speech. Not only is lying highly unethical, but if you are caught lying, your audience will deem you untrustworthy and perceive everything you are saying as untrustworthy. Many speakers have attempted to lie to an audience because it will serve their own purposes or even because they believe their message is in their audience’s best interest, but lying is one of the fastest ways to turn off an audience and get them to distrust both the speaker and the message.

The third characteristic of credibility to establish during the introduction is the sense of caring/goodwill. While some unethical speakers can attempt to manipulate an audience’s perception that the speaker cares, ethical speakers truly do care about their audiences and have their audience’s best interests in mind while speaking. Often speakers must speak in front of audiences that may be hostile toward the speaker’s message. In these cases, it is very important for the speaker to explain that he or she really does believe her or his message is in the audience’s best interest. One way to show that you have your audience’s best interests in mind is to acknowledge disagreement from the start:

Today I’m going to talk about why I believe we should enforce stricter immigration laws in the United States. I realize that many of you will disagree with me on this topic. I used to believe that open immigration was a necessity for the United States to survive and thrive, but after researching this topic, I’ve changed my mind. While I may not change all of your minds today, I do ask that you listen with an open mind, set your personal feelings on this topic aside, and judge my arguments on their merits.

While clearly not all audience members will be open or receptive to opening their minds and listening to your arguments, by establishing that there is known disagreement, you are telling the audience that you understand their possible views and are not trying to attack their intellect or their opinions.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know “in a nutshell” what you are going to talk about. With a good thesis statement you will fulfill four basic functions: you express your specific purpose, provide a way to organize your main points, make your research more effective, and enhance your delivery.

Express Your Specific Purpose

To orient your audience, you need to be as clear as possible about your meaning. A strong thesis will prepare your audience effectively for the points that will follow. Here are two examples:

- “Today, I want to discuss academic cheating.” (weak example)

- “Today, I will clarify exactly what plagiarism is and give examples of its different types so that you can see how it leads to a loss of creative learning interaction.” (strong example)

The weak statement will probably give the impression that you have no clear position about your topic because you haven’t said what that position is. Additionally, the term “academic cheating” can refer to many behaviors—acquiring test questions ahead of time, copying answers, changing grades, or allowing others to do your coursework—so the specific topic of the speech is still not clear to the audience.

The strong statement not only specifies plagiarism but also states your specific concern (loss of creative learning interaction).

Provide a Way to Organize Your Main Points

A thesis statement should appear, almost verbatim, toward the end of the introduction to a speech. A thesis statement helps the audience get ready to listen to the arrangement of points that follow. Many speakers say that if they can create a strong thesis sentence, the rest of the speech tends to develop with relative ease. On the other hand, when the thesis statement is not very clear, creating a speech is an uphill battle.

When your thesis statement is sufficiently clear and decisive, you will know where you stand about your topic and where you intend to go with your speech. Having a clear thesis statement is especially important if you know a great deal about your topic or you have strong feelings about it. If this is the case for you, you need to know exactly what you are planning on talking about in order to fit within specified time limitations. Knowing where you are and where you are going is the entire point in establishing a thesis statement; it makes your speech much easier to prepare and to present.

Let’s say you have a fairly strong thesis statement, and that you’ve already brainstormed a list of information that you know about the topic. Chances are your list is too long and has no focus. Using your thesis statement, you can select only the information that (1) is directly related to the thesis and (2) can be arranged in a sequence that will make sense to the audience and will support the thesis. In essence, a strong thesis statement helps you keep useful information and weed out less useful information.

Make Your Research More Effective

If you begin your research with only a general topic in mind, you run the risk of spending hours reading mountains of excellent literature about your topic. However, mountains of literature do not always make coherent speeches. You may have little or no idea of how to tie your research all together, or even whether you should tie it together. If, on the other hand, you conduct your research with a clear thesis statement in mind, you will be better able to zero in only on material that directly relates to your chosen thesis statement. Let’s look at an example that illustrates this point:

Many traffic accidents involve drivers older than fifty-five.

While this statement may be true, you could find industrial, medical, insurance literature that can drone on ad infinitum about the details of all such accidents in just one year. Instead, focusing your thesis statement will help you narrow the scope of information you will be searching for while gathering information. Here’s an example of a more focused thesis statement:

Three factors contribute to most accidents involving drivers over fifty-five years of age: failing eyesight, slower reflexes, and rapidly changing traffic conditions.

This framing is somewhat better. This thesis statement at least provides three possible main points and some keywords for your electronic catalog search. However, if you want your audience to understand the context of older people at the wheel, consider something like:

Mature drivers over fifty-five years of age must cope with more challenging driving conditions than existed only one generation ago: more traffic moving at higher speeds, the increased imperative for quick driving decisions, and rapidly changing ramp and cloverleaf systems. Because of these challenges, I want my audience to believe that drivers over the age of sixty-five should be required to pass a driving test every five years.

This framing of the thesis provides some interesting choices. First, several terms need to be defined, and these definitions might function surprisingly well in setting the tone of the speech. Your definitions of words like “generation,” “quick driving decisions,” and “cloverleaf systems” could jolt your audience out of assumptions they have taken for granted as truth.

Second, the framing of the thesis provides you with a way to describe the specific changes as they have occurred between, say, 1970 and 2010. How much, and in what ways, have the volume and speed of traffic changed? Why are quick decisions more critical now? What is a “cloverleaf,” and how does any driver deal cognitively with exiting in the direction seemingly opposite to the desired one? Questions like this, suggested by your own thesis statement, can lead to a strong, memorable speech.

Enhance Your Delivery

When your thesis is not clear to you, your listeners will be even more clueless than you are—but if you have a good clear thesis statement, your speech becomes clear to your listeners. When you stand in front of your audience presenting your introduction, you can vocally emphasize the essence of your speech, expressed as your thesis statement. Many speakers pause for a half second, lower their vocal pitch slightly, slow down a little, and deliberately present the thesis statement, the one sentence that encapsulates its purpose. When this is done effectively, the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech is driven home for an audience.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech as we discussed them in Chapter 6 “Finding a Purpose and Selecting a Topic” .

Choose Your Topic

The first step in writing a good thesis statement was originally discussed in Chapter 6 “Finding a Purpose and Selecting a Topic” when we discussed how to find topics. Once you have a general topic, you are ready to go to the second step of creating a thesis statement.

Narrow Your Topic

One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to ten-minute speech. While five to ten minutes may sound like a long time to new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

First, is your thesis statement narrow or is it a broad overgeneralization of a topic? An overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

The second question to ask yourself when narrowing a topic is whether your speech’s topic is one clear topic or multiple topics. A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and gay marriage should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: “Today we’re going to examine the legalization and regulation of the oldest profession in the state of Nevada.” In this case, we’re focusing our topic to how one state has handled the legalization and regulation of prostitution.

The last question a speaker should ask when making sure a topic is sufficiently narrow is whether the topic has direction. If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Sentence

Once you’ve narrowed your topic to something that is reasonably manageable given the constraints placed on your speech, you can then formalize that topic as a complete sentence. For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

Add Your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

This function only applies if you are giving a speech to persuade. If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “This speech is going to analyze Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin.”

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

Use the Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown in Table 9.1 “Thesis Checklist”

Table 9.1 Thesis Checklist

Preview of Speech

The final part of an introduction contains a preview of the major points to be covered within your speech. I’m sure we’ve all seen signs that have three cities listed on them with the mileage to reach each city. This mileage sign is an indication of what is to come. A preview works the same way. A preview foreshadows what the main body points will be in the speech. For example, to preview a speech on bullying in the workplace, one could say, “To understand the nature of bullying in the modern workplace, I will first define what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying, I will then discuss the common characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets, and lastly, I will explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.” In this case, each of the phrases mentioned in the preview would be a single distinct point made in the speech itself. In other words, the first major body point in this speech would examine what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying; the second major body point in this speech would discuss the common characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets; and lastly, the third body point in this speech would explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.

Key Takeaways

- Linking the attention-getter to the speech topic is essential so that you maintain audience attention and so that the relevance of the attention-getter is clear to your audience.

- Establishing how your speech topic is relevant and important shows the audience why they should listen to your speech.

- To be an effective speaker, you should convey all three components of credibility, competence, trustworthiness, and caring/goodwill, by the content and delivery of your introduction.

- A clear thesis statement is essential to provide structure for a speaker and clarity for an audience.

- An effective preview identifies the specific main points that will be present in the speech body.

- Make a list of the attention-getting devices you might use to give a speech on the importance of recycling. Which do you think would be most effective? Why?

- Create a thesis statement for a speech related to the topic of collegiate athletics. Make sure that your thesis statement is narrow enough to be adequately covered in a five- to six-minute speech.

- Discuss with a partner three possible body points you could utilize for the speech on the topic of volunteerism.

- Fill out the introduction worksheet to help work through your introduction for your next speech. Please make sure that you answer all the questions clearly and concisely.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

IMAGES

VIDEO