The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever. This is how

With schools shut across the world, millions of children have had to adapt to new types of learning. Image: REUTERS/Gonzalo Fuentes

.chakra .wef-spn4bz{transition-property:var(--chakra-transition-property-common);transition-duration:var(--chakra-transition-duration-fast);transition-timing-function:var(--chakra-transition-easing-ease-out);cursor:pointer;text-decoration:none;outline:2px solid transparent;outline-offset:2px;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:hover,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-hover]{text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-spn4bz:focus-visible,.chakra .wef-spn4bz[data-focus-visible]{box-shadow:var(--chakra-shadows-outline);} Cathy Li

Farah lalani.

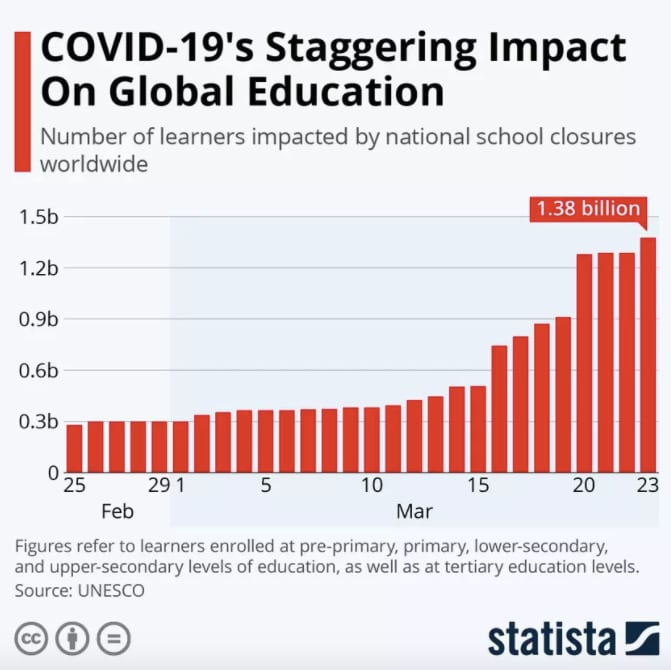

- The COVID-19 has resulted in schools shut all across the world. Globally, over 1.2 billion children are out of the classroom.

- As a result, education has changed dramatically, with the distinctive rise of e-learning, whereby teaching is undertaken remotely and on digital platforms.

- Research suggests that online learning has been shown to increase retention of information, and take less time, meaning the changes coronavirus have caused might be here to stay.

While countries are at different points in their COVID-19 infection rates, worldwide there are currently more than 1.2 billion children in 186 countries affected by school closures due to the pandemic. In Denmark, children up to the age of 11 are returning to nurseries and schools after initially closing on 12 March , but in South Korea students are responding to roll calls from their teachers online .

With this sudden shift away from the classroom in many parts of the globe, some are wondering whether the adoption of online learning will continue to persist post-pandemic, and how such a shift would impact the worldwide education market.

Even before COVID-19, there was already high growth and adoption in education technology, with global edtech investments reaching US$18.66 billion in 2019 and the overall market for online education projected to reach $350 Billion by 2025 . Whether it is language apps , virtual tutoring , video conferencing tools, or online learning software , there has been a significant surge in usage since COVID-19.

How is the education sector responding to COVID-19?

In response to significant demand, many online learning platforms are offering free access to their services, including platforms like BYJU’S , a Bangalore-based educational technology and online tutoring firm founded in 2011, which is now the world’s most highly valued edtech company . Since announcing free live classes on its Think and Learn app, BYJU’s has seen a 200% increase in the number of new students using its product, according to Mrinal Mohit, the company's Chief Operating Officer.

Tencent classroom, meanwhile, has been used extensively since mid-February after the Chinese government instructed a quarter of a billion full-time students to resume their studies through online platforms. This resulted in the largest “online movement” in the history of education with approximately 730,000 , or 81% of K-12 students, attending classes via the Tencent K-12 Online School in Wuhan.

Have you read?

The future of jobs report 2023, how to follow the growth summit 2023.

Other companies are bolstering capabilities to provide a one-stop shop for teachers and students. For example, Lark, a Singapore-based collaboration suite initially developed by ByteDance as an internal tool to meet its own exponential growth, began offering teachers and students unlimited video conferencing time, auto-translation capabilities, real-time co-editing of project work, and smart calendar scheduling, amongst other features. To do so quickly and in a time of crisis, Lark ramped up its global server infrastructure and engineering capabilities to ensure reliable connectivity.

Alibaba’s distance learning solution, DingTalk, had to prepare for a similar influx: “To support large-scale remote work, the platform tapped Alibaba Cloud to deploy more than 100,000 new cloud servers in just two hours last month – setting a new record for rapid capacity expansion,” according to DingTalk CEO, Chen Hang.

Some school districts are forming unique partnerships, like the one between The Los Angeles Unified School District and PBS SoCal/KCET to offer local educational broadcasts, with separate channels focused on different ages, and a range of digital options. Media organizations such as the BBC are also powering virtual learning; Bitesize Daily , launched on 20 April, is offering 14 weeks of curriculum-based learning for kids across the UK with celebrities like Manchester City footballer Sergio Aguero teaching some of the content.

What does this mean for the future of learning?

While some believe that the unplanned and rapid move to online learning – with no training, insufficient bandwidth, and little preparation – will result in a poor user experience that is unconducive to sustained growth, others believe that a new hybrid model of education will emerge, with significant benefits. “I believe that the integration of information technology in education will be further accelerated and that online education will eventually become an integral component of school education,“ says Wang Tao, Vice President of Tencent Cloud and Vice President of Tencent Education.

There have already been successful transitions amongst many universities. For example, Zhejiang University managed to get more than 5,000 courses online just two weeks into the transition using “DingTalk ZJU”. The Imperial College London started offering a course on the science of coronavirus, which is now the most enrolled class launched in 2020 on Coursera .

Many are already touting the benefits: Dr Amjad, a Professor at The University of Jordan who has been using Lark to teach his students says, “It has changed the way of teaching. It enables me to reach out to my students more efficiently and effectively through chat groups, video meetings, voting and also document sharing, especially during this pandemic. My students also find it is easier to communicate on Lark. I will stick to Lark even after coronavirus, I believe traditional offline learning and e-learning can go hand by hand."

These 3 charts show the global growth in online learning

The challenges of online learning.

There are, however, challenges to overcome. Some students without reliable internet access and/or technology struggle to participate in digital learning; this gap is seen across countries and between income brackets within countries. For example, whilst 95% of students in Switzerland, Norway, and Austria have a computer to use for their schoolwork, only 34% in Indonesia do, according to OECD data .

In the US, there is a significant gap between those from privileged and disadvantaged backgrounds: whilst virtually all 15-year-olds from a privileged background said they had a computer to work on, nearly 25% of those from disadvantaged backgrounds did not. While some schools and governments have been providing digital equipment to students in need, such as in New South Wales , Australia, many are still concerned that the pandemic will widenthe digital divide .

Is learning online as effective?

For those who do have access to the right technology, there is evidence that learning online can be more effective in a number of ways. Some research shows that on average, students retain 25-60% more material when learning online compared to only 8-10% in a classroom. This is mostly due to the students being able to learn faster online; e-learning requires 40-60% less time to learn than in a traditional classroom setting because students can learn at their own pace, going back and re-reading, skipping, or accelerating through concepts as they choose.

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of online learning varies amongst age groups. The general consensus on children, especially younger ones, is that a structured environment is required , because kids are more easily distracted. To get the full benefit of online learning, there needs to be a concerted effort to provide this structure and go beyond replicating a physical class/lecture through video capabilities, instead, using a range of collaboration tools and engagement methods that promote “inclusion, personalization and intelligence”, according to Dowson Tong, Senior Executive Vice President of Tencent and President of its Cloud and Smart Industries Group.

Since studies have shown that children extensively use their senses to learn, making learning fun and effective through use of technology is crucial, according to BYJU's Mrinal Mohit. “Over a period, we have observed that clever integration of games has demonstrated higher engagement and increased motivation towards learning especially among younger students, making them truly fall in love with learning”, he says.

A changing education imperative

It is clear that this pandemic has utterly disrupted an education system that many assert was already losing its relevance . In his book, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century , scholar Yuval Noah Harari outlines how schools continue to focus on traditional academic skills and rote learning , rather than on skills such as critical thinking and adaptability, which will be more important for success in the future. Could the move to online learning be the catalyst to create a new, more effective method of educating students? While some worry that the hasty nature of the transition online may have hindered this goal, others plan to make e-learning part of their ‘new normal’ after experiencing the benefits first-hand.

The importance of disseminating knowledge is highlighted through COVID-19

Major world events are often an inflection point for rapid innovation – a clear example is the rise of e-commerce post-SARS . While we have yet to see whether this will apply to e-learning post-COVID-19, it is one of the few sectors where investment has not dried up . What has been made clear through this pandemic is the importance of disseminating knowledge across borders, companies, and all parts of society. If online learning technology can play a role here, it is incumbent upon all of us to explore its full potential.

Our education system is losing relevance. Here's how to unleash its potential

3 ways the coronavirus pandemic could reshape education, celebrities are helping the uk's schoolchildren learn during lockdown, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Stay up to date:

Education, gender and work, related topics:.

.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1v7zi92{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-ugz4zj{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-base);font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-larger);color:var(--chakra-colors-yellow);}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-ugz4zj{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-large);}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

Forum stories .chakra .wef-dog8kz{margin-top:var(--chakra-space-base);margin-bottom:var(--chakra-space-base);line-height:var(--chakra-lineheights-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontweights-normal);} newsletter.

Bringing you weekly curated insights and analysis on the global issues that matter.

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:flex;align-items:center;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{flex:1;justify-self:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-2sx2oi{display:inline-flex;vertical-align:middle;padding-inline-start:var(--chakra-space-1);padding-inline-end:var(--chakra-space-1);text-transform:uppercase;font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smallest);border-radius:var(--chakra-radii-base);font-weight:var(--chakra-fontWeights-bold);background:none;box-shadow:var(--badge-shadow);align-items:center;line-height:var(--chakra-lineHeights-short);letter-spacing:1.25px;padding:var(--chakra-space-0);white-space:normal;color:var(--chakra-colors-greyLight);box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width: 37.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-smaller);}}@media screen and (min-width: 56.5rem){.chakra .wef-2sx2oi{font-size:var(--chakra-fontSizes-base);}} See all

The top global health stories from 2024

Shyam Bishen

December 17, 2024

5 ways generative AI could transform clinical trials

What is health equity and how can it help achieve universal health coverage?

Universal health coverage: a global problem with local solutions

Intelligent Clinical Trials: Using Generative AI to Fast-Track Therapeutic Innovations

Meet Liv, the AI helper supporting people recently diagnosed with dementia

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay On Online Education: In 100 Words, 150 Words, and 200 Words

- Updated on

- December 13, 2024

Online education has emerged as a significant transformation in the global education landscape, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic . This essay explores the various facets of online education, from its inception to its advantages and disadvantages and its impact on learners and educators alike. The evolution of online education presents a new horizon for accessible and flexible learning .

Table of Contents

- 1 Paragraph on Online Education in 100 words

- 2 Essay on Online Education in 150 words

- 3 Essay on Online Education in 250 words

- 4 Short Essay on Online Education

Also Read: English Essay Topics

Paragraph on Online Education in 100 words

Online education is a modern educational pattern where students access instructional content through the internet. This innovative approach has gained immense popularity, especially after the pandemic. Due to its convenience and adaptability, individuals are more inclined towards this way of learning and teaching. It has enabled students of all ages to acquire knowledge from the comfort of their homes crossing all the geographical barriers. Online education offers a diverse range of courses and resources and fosters continuous learning. However, it also presents challenges, such as dependency on technology and potential disengagement from the physical world.

Also Read: The Beginner’s Guide to Writing an Essay

Essay on Online Education in 150 words

Online education marks a revolutionary shift in how we acquire knowledge. It harnesses the power of the internet to deliver educational content to students, making learning more flexible and accessible. Technology advancements have accelerated the development of online education, enabling educational institutions to provide a wide range of courses and programmes through digital platforms.

One of the primary advantages of online education is its ability to cater to a diverse audience, regardless of geographical location or physical limitations. It reduces the need for travelling to study and offers a cost-effective alternative to traditional classroom learning. However, online education also comes with its challenges. It requires self-discipline and motivation as students often learn independently. Additionally, prolonged screen time can have adverse effects on students’ physical and mental well-being, potentially leading to social disconnection. Online education is a smart way to impact education but its benefits and consequences should be measured well.

Essay on Online Education in 250 words

Online education has witnessed remarkable growth in recent years, with the internet serving as the platform for delivering educational content. This transformation has been accelerated, especially in response to the global pandemic. Online education crosses all the boundaries of traditional learning, offering students the opportunity to acquire knowledge and skills from anywhere in the world.

One of the most compelling aspects of online education is its flexibility. Learners can access course materials and engage with instructors at their convenience, breaking free from rigid schedules. Moreover, this mode of education has expanded access to a vast array of courses, allowing individuals to pursue their interests and career goals without geographical constraints.

However, it’s important to acknowledge the challenges associated with online education. Limited face-to-face interaction can lead to feelings of isolation among the students. It demands a high degree of self-discipline, as students must navigate the coursework independently. Prolonged screen time can have adverse effects on health and may lead to a sense of disconnection from society. Technical issues can also hinder the online learning experience for some students. For underprivileged students, the access to Internet can be challenging.

In conclusion, online education represents a significant shift in how we approach learning. It offers unprecedented access and flexibility but also requires learners to adapt to a more self-directed approach to education. Striking a balance between the benefits and challenges of online education is key to harnessing its full potential. As technology continues to improve, online education will likely become an even more integral part of our educational landscape.

Also Read: Essay on Fire Safety in 200 and 500+ words in English for Students

Short Essay on Online Education

Find a sample essay on online education below:

Online education is a modern educational pattern where students access instructional content through the internet. This innovative approach has gained immense popularity, especially after the pandemic.

Advantages include flexibility, cost-effectiveness, accessibility, and the ability to learn at your own pace from anywhere.

An organised thought backed up by proof and examples is the key to writing a convincing essay. Create a clear thesis statement in the introduction, follow a logical order of points, and then summarise your main points.

Students, working professionals, and individuals looking to upskill or learn new hobbies can benefit from online education programs.

To improve readability, use clear and concise language, break your essay into paragraphs with clear topic sentences, and vary your sentence structure.

If you’re struggling to meet the word count, review your content to see if you can expand on your ideas, provide more examples, or include additional details to support your arguments. Additionally, check for any irrelevant information that can be removed.

The pandemic accelerated the adoption of online education worldwide, making it a primary mode of learning during lockdowns.

The future seems promising, with developments in virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and hybrid learning models improving accessibility and quality.

Related Reads

We hope that this essay on Online Education helps. For more amazing daily reads related to essay writing , stay tuned with Leverage Edu .

Manasvi Kotwal

Manasvi's flair in writing abilities is derived from her past experience of working with bootstrap start-ups, Advertisement and PR agencies as well as freelancing. She's currently working as a Content Marketing Associate at Leverage Edu to be a part of its thriving ecosystem.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2025

September 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

Online education in the post-COVID era

- Barbara B. Lockee 1

Nature Electronics volume 4 , pages 5–6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

145k Accesses

255 Citations

336 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The coronavirus pandemic has forced students and educators across all levels of education to rapidly adapt to online learning. The impact of this — and the developments required to make it work — could permanently change how education is delivered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning. And while online and distance learning has been used before to maintain continuity in education, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes 1 , the scale of the current crisis is unprecedented. Speculation has now also begun about what the lasting effects of this will be and what education may look like in the post-COVID era. For some, an immediate retreat to the traditions of the physical classroom is required. But for others, the forced shift to online education is a moment of change and a time to reimagine how education could be delivered 2 .

Looking back

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. (The term ‘emergency remote teaching’ was coined in the early stages of the pandemic to describe the temporary nature of this transition 3 .) In some cases, instruction shifted online, then returned to the physical classroom, and then shifted back online due to further surges in the rate of infection. In other cases, instruction was offered using a combination of remote delivery and face-to-face: that is, students can attend online or in person (referred to as the HyFlex model 4 ). In either case, instructors just had to figure out how to make it work, considering the affordances and constraints of the specific learning environment to create learning experiences that were feasible and effective.

The use of varied delivery modes does, in fact, have a long history in education. Mechanical (and then later electronic) teaching machines have provided individualized learning programmes since the 1950s and the work of B. F. Skinner 5 , who proposed using technology to walk individual learners through carefully designed sequences of instruction with immediate feedback indicating the accuracy of their response. Skinner’s notions formed the first formalized representations of programmed learning, or ‘designed’ learning experiences. Then, in the 1960s, Fred Keller developed a personalized system of instruction 6 , in which students first read assigned course materials on their own, followed by one-on-one assessment sessions with a tutor, gaining permission to move ahead only after demonstrating mastery of the instructional material. Occasional class meetings were held to discuss concepts, answer questions and provide opportunities for social interaction. A personalized system of instruction was designed on the premise that initial engagement with content could be done independently, then discussed and applied in the social context of a classroom.

These predecessors to contemporary online education leveraged key principles of instructional design — the systematic process of applying psychological principles of human learning to the creation of effective instructional solutions — to consider which methods (and their corresponding learning environments) would effectively engage students to attain the targeted learning outcomes. In other words, they considered what choices about the planning and implementation of the learning experience can lead to student success. Such early educational innovations laid the groundwork for contemporary virtual learning, which itself incorporates a variety of instructional approaches and combinations of delivery modes.

Online learning and the pandemic

Fast forward to 2020, and various further educational innovations have occurred to make the universal adoption of remote learning a possibility. One key challenge is access. Here, extensive problems remain, including the lack of Internet connectivity in some locations, especially rural ones, and the competing needs among family members for the use of home technology. However, creative solutions have emerged to provide students and families with the facilities and resources needed to engage in and successfully complete coursework 7 . For example, school buses have been used to provide mobile hotspots, and class packets have been sent by mail and instructional presentations aired on local public broadcasting stations. The year 2020 has also seen increased availability and adoption of electronic resources and activities that can now be integrated into online learning experiences. Synchronous online conferencing systems, such as Zoom and Google Meet, have allowed experts from anywhere in the world to join online classrooms 8 and have allowed presentations to be recorded for individual learners to watch at a time most convenient for them. Furthermore, the importance of hands-on, experiential learning has led to innovations such as virtual field trips and virtual labs 9 . A capacity to serve learners of all ages has thus now been effectively established, and the next generation of online education can move from an enterprise that largely serves adult learners and higher education to one that increasingly serves younger learners, in primary and secondary education and from ages 5 to 18.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to have a lasting effect on lesson design. The constraints of the pandemic provided an opportunity for educators to consider new strategies to teach targeted concepts. Though rethinking of instructional approaches was forced and hurried, the experience has served as a rare chance to reconsider strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context. In particular, greater variance in teaching and learning activities will continue to question the importance of ‘seat time’ as the standard on which educational credits are based 10 — lengthy Zoom sessions are seldom instructionally necessary and are not aligned with the psychological principles of how humans learn. Interaction is important for learning but forced interactions among students for the sake of interaction is neither motivating nor beneficial.

While the blurring of the lines between traditional and distance education has been noted for several decades 11 , the pandemic has quickly advanced the erasure of these boundaries. Less single mode, more multi-mode (and thus more educator choices) is becoming the norm due to enhanced infrastructure and developed skill sets that allow people to move across different delivery systems 12 . The well-established best practices of hybrid or blended teaching and learning 13 have served as a guide for new combinations of instructional delivery that have developed in response to the shift to virtual learning. The use of multiple delivery modes is likely to remain, and will be a feature employed with learners of all ages 14 , 15 . Future iterations of online education will no longer be bound to the traditions of single teaching modes, as educators can support pedagogical approaches from a menu of instructional delivery options, a mix that has been supported by previous generations of online educators 16 .

Also significant are the changes to how learning outcomes are determined in online settings. Many educators have altered the ways in which student achievement is measured, eliminating assignments and changing assessment strategies altogether 17 . Such alterations include determining learning through strategies that leverage the online delivery mode, such as interactive discussions, student-led teaching and the use of games to increase motivation and attention. Specific changes that are likely to continue include flexible or extended deadlines for assignment completion 18 , more student choice regarding measures of learning, and more authentic experiences that involve the meaningful application of newly learned skills and knowledge 19 , for example, team-based projects that involve multiple creative and social media tools in support of collaborative problem solving.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, technological and administrative systems for implementing online learning, and the infrastructure that supports its access and delivery, had to adapt quickly. While access remains a significant issue for many, extensive resources have been allocated and processes developed to connect learners with course activities and materials, to facilitate communication between instructors and students, and to manage the administration of online learning. Paths for greater access and opportunities to online education have now been forged, and there is a clear route for the next generation of adopters of online education.

Before the pandemic, the primary purpose of distance and online education was providing access to instruction for those otherwise unable to participate in a traditional, place-based academic programme. As its purpose has shifted to supporting continuity of instruction, its audience, as well as the wider learning ecosystem, has changed. It will be interesting to see which aspects of emergency remote teaching remain in the next generation of education, when the threat of COVID-19 is no longer a factor. But online education will undoubtedly find new audiences. And the flexibility and learning possibilities that have emerged from necessity are likely to shift the expectations of students and educators, diminishing further the line between classroom-based instruction and virtual learning.

Mackey, J., Gilmore, F., Dabner, N., Breeze, D. & Buckley, P. J. Online Learn. Teach. 8 , 35–48 (2012).

Google Scholar

Sands, T. & Shushok, F. The COVID-19 higher education shove. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/3o2vHbX (16 October 2020).

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, M. A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/38084Lh (27 March 2020).

Beatty, B. J. (ed.) Hybrid-Flexible Course Design Ch. 1.4 https://go.nature.com/3o6Sjb2 (EdTech Books, 2019).

Skinner, B. F. Science 128 , 969–977 (1958).

Article Google Scholar

Keller, F. S. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1 , 79–89 (1968).

Darling-Hammond, L. et al. Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond (Learning Policy Institute, 2020).

Fulton, C. Information Learn. Sci . 121 , 579–585 (2020).

Pennisi, E. Science 369 , 239–240 (2020).

Silva, E. & White, T. Change The Magazine Higher Learn. 47 , 68–72 (2015).

McIsaac, M. S. & Gunawardena, C. N. in Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (ed. Jonassen, D. H.) Ch. 13 (Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996).

Irvine, V. The landscape of merging modalities. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/2MjiBc9 (26 October 2020).

Stein, J. & Graham, C. Essentials for Blended Learning Ch. 1 (Routledge, 2020).

Maloy, R. W., Trust, T. & Edwards, S. A. Variety is the spice of remote learning. Medium https://go.nature.com/34Y1NxI (24 August 2020).

Lockee, B. J. Appl. Instructional Des . https://go.nature.com/3b0ddoC (2020).

Dunlap, J. & Lowenthal, P. Open Praxis 10 , 79–89 (2018).

Johnson, N., Veletsianos, G. & Seaman, J. Online Learn. 24 , 6–21 (2020).

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Garrison, D. R. Assessment in Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2013).

Conrad, D. & Openo, J. Assessment Strategies for Online Learning: Engagement and Authenticity (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2018).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Barbara B. Lockee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara B. Lockee .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lockee, B.B. Online education in the post-COVID era. Nat Electron 4 , 5–6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Download citation

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A comparative study on the effectiveness of online and in-class team-based learning on student performance and perceptions in virtual simulation experiments.

BMC Medical Education (2024)

Enhancing learner affective engagement: The impact of instructor emotional expressions and vocal charisma in asynchronous video-based online learning

- Hung-Yue Suen

- Kuo-En Hung

Education and Information Technologies (2024)

Development and validation of the antecedents to videoconference fatigue scale in higher education (AVFS-HE)

- Benjamin J. Li

- Andrew Z. H. Yee

Leveraging privacy profiles to empower users in the digital society

- Davide Di Ruscio

- Paola Inverardi

- Phuong T. Nguyen

Automated Software Engineering (2024)

Global public concern of childhood and adolescence suicide: a new perspective and new strategies for suicide prevention in the post-pandemic era

- Dong Keon Yon

World Journal of Pediatrics (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Advertisement

Impact of online learning on student's performance and engagement: a systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 01 November 2024

- Volume 3 , article number 205 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Catherine Nabiem Akpen ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-2218-2254 1 ,

- Stephen Asaolu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7116-6468 1 ,

- Sunday Atobatele ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1947-2561 2 ,

- Hilary Okagbue ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3779-9763 1 &

- Sidney Sampson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5303-5475 2

10k Accesses

Explore all metrics

The rapid shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly influenced educational practices worldwide and increased the use of online learning platforms. This systematic review examines the impact of online learning on student engagement and performance, providing a comprehensive analysis of existing studies. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline, a thorough literature search was conducted across different databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR for articles published between 2019 and 2024. The review included peer-reviewed studies that assess student engagement and performance in online learning environments. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 18 studies were selected for detailed analysis. The analysis revealed varied impacts of online learning on student performance and engagement. Some studies reported improved academic performance due to the flexibility and accessibility of online learning, enabling students to learn at their own pace. However, other studies highlighted challenges such as decreased engagement and isolation, and reduced interaction with instructors and peers. The effectiveness of online learning was found to be influenced by factors such as the quality of digital tools, good internet, and student motivation. Maintaining student engagement remains a challenge, effective strategies to improve student engagement such as interactive elements, like discussion forums and multimedia resources, alongside adequate instructor-student interactions, were critical in improving both engagement and performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the Factors Affecting Student Academic Performance in Online Programs: A Literature Review

A meta-analysis addressing the relationship between self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance in online higher education

Online engagement and performance on formative assessments mediate the relationship between attendance and course performance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Online learning also referred to as E-learning or remote learning is essentially a web-based program that gives learners access to knowledge or information whenever needed, regardless of their proximity to a location or time constraints [ 1 ]. This form of learning has been around for a while, it started in the late 1990s and it has advanced quickly. It has been considered a good choice, particularly for adult learners [ 2 ].

Online education promotes a student-centred approach, whereby students are expected to actively participate in the learning process. The digital tools used in online learning include interactive elements, computers, mobile devices, the internet, and other devices that allow students to receive and share knowledge [ 3 ]. Different types of online learning exist, such as microlearning, individualized learning, synchronous, asynchronous, blended, and massive open online courses [ 2 ]. Online learning offers several advantages to students, such as its adaptability to individual needs, ease, and flexibility in terms of involvement. With user-friendly online learning applications on their personal computers (PCs) or laptops, students can take part in their online courses from any convenient place, they can take specific courses with less time and location restrictions [ 4 ].

Learning experiences and academic success of students are some of the difficulties of online education [ 5 ]. Furthermore, while technology facilitates accessibility and ease of use of online learning platforms, it can also have restrictive effects, where many students struggle to gain internet access [ 6 ], in turn causes problems with participation and attendance in virtual classes, which makes it difficult to adopt online learning platforms [ 7 ]. Other issues with e-learning include educational policy, learning pedagogy, accessibility, affordability, and flexibility [ 8 ]. Many developing countries have substantial issues with reliable internet connection and access to digital devices, especially among economically backward children [ 9 ]. Maintaining student engagement in an online classroom can be more difficult than in a traditional face-to-face setting [ 10 ]. Even with all the advantages of online learning, there is reduced interaction between students and course facilitators. Another barrier to online learning is the lack of opportunities for human connection, which was thought to be essential for creating peer support and creating in-depth group discussions on the subject [ 11 ].

Over the past four years, COVID-19 has spread over the world, forcing schools to close, hence the pandemic compelled educators and learners at every level to swiftly adapt to online learning to curb the spread of the disease while ensuring continuous education [ 12 ]. The emergence of the pandemic rendered traditional face-to-face teaching and training methods unfeasible [ 13 ]. Some studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 ] acknowledged that the move to online learning was significant and sudden, but that it was also necessary to continue the learning process. This abrupt change sparked an argument regarding the standard of learning and satisfaction with learning among students [ 17 ].

While there are similarities between face-to-face (F2F) and online learning, they still differ in several ways [ 18 ], some of the similarities are: prerequisites for students include attendance, comprehension of the subject matter, turning in homework, and completion of group projects. The teachers still need to create curricula, enhance the quality of their instruction, respond to inquiries from students, inspire them to learn, and grade assignments [ 19 ]. One difference between online learning and F2F learning is the fact that online learning is student-centred and necessitates active learning while F2F learning is teacher-centred and demands passive learning from the student [ 19 ]. Another difference is teaching and learning has to happen at the same time and location in face-to-face learning, while online learning is not restricted by time or location [ 20 ]. Online learning allows teaching and learning to be done separately using internet-based information delivery systems [ 21 ].

Finding more efficient strategies to increase student engagement in online learning settings is necessary, as the absence of F2F interactions between students and instructors or among students continues to be a significant issue with online learning [ 20 ]. Student engagement has been defined as how involved or interested students appear to be in their learning and how connected they are to their classes, their institutions, and each other [ 22 ]. Engagement has been pointed out as a major dimension of students’ level and quality of learning, and is associated with improvement in their academic achievement, their persistence versus dropout, as well as their personal and cognitive development [ 23 ]. In an online setting, student engagement is equally crucial to their success and performance [ 24 ].

Change in learning delivery method is accompanied by inquiries when assessing whether online education is a practical replacement for traditional classroom instruction, cost–benefit evaluation, student experience, and student achievement are now being carefully considered [ 19 ]. This decision-making process will most likely continue if students seek greater learning opportunities and technological advances [ 19 ].

An individual's academic performance is significant to their success during their time in an educational institution [ 25 ], students' academic achievement is one indicator of their educational accomplishment. However, it is frequently seen that while student learning capacities are average, the demands placed on them for academic achievement are rising. This is the reason why the student's academic performance success rate is below par [ 25 ].

Numerous authors [ 11 , 13 , 18 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ] have examined how students and teachers view online learning, but it is still important to understand how much students are learning from these platforms. After all, student performance determines whether a subject or course is successful or unsuccessful.

The increase in the use of online learning calls for a careful analysis of its impact on student performance and engagement. Investigating the online learning experiences of students will guide education policymakers such as ministries, departments, and agencies in both the public and private sectors in the evaluation of the potential pros and cons of adopting online education against F2F education [ 30 ]

Given the foregoing, this study was carried out to; (1) investigate the online learning experiences of students, (2) review the academic performance of students using online learning platforms, and (3) explore the levels of students’ engagement when learning using online platforms.

2 Methodology

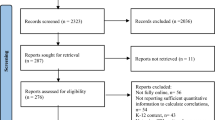

The study was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [ 31 ].

2.1 Search strategy and databases used

PubMed, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR were databases used to search for articles using identified search terms. The three data bases were selected for their extensive coverage of health sciences, social sciences and educational articles. The articles searched were between the years 2019–2024, this is because online learning became popular during the COVID-19 pandemic which started in 2019. Only English, open-access, and free full-text articles were selected for review, this is to ensure that the data analysed are publicly available to ascertain transparency and reproducibility of the review. The search was carried out in February 2024. The search strategy terms used are shown in Table 1 .

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles included for review were studies conducted on students enrolled in any field in a higher institution. Only articles in English language that were published between 2019 and 2024 which assessed student performance and engagement were included.

Articles excluded are studies involving pupils (students in primary school), articles not written in English language, and those published before 2019. Also, studies that did not follow the declaration of Helsinki on research ethics and without clear evidence of ethical consideration and approval were excluded.

2.3 Search outcomes

A total of 1078 articles were obtained from the databases searched. Four articles were duplicated and eliminated from the review. After the elimination of duplicates, titles, and abstracts were used to evaluate the remaining 1074 articles. These articles were screened based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 1052 studies were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts. Complete texts of 22 articles were read and four were found to be irrelevant to the review, a total of 18 articles were used for the systematic review.

The PRISMA flowchart shown in Fig. 1 illustrates the procedure used to screen and assess the articles.

A PRISMA flow chart of studies included in the systematic review

2.4 Data analysis

A data synthesis table was developed to collect relevant information on the author, year study was conducted, study design, study location, sample methodology, sample size, population, assessment tool, findings on student performance and student engagement, other findings, and limitations. Data was collected about whether students’ performance and engagement improved or declined following the introduction of online learning in their education. Data about the extent of the improvement or decline was also collected.

2.5 Quality appraisal

A quality assessment was carried out using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) developed to appraise systematic reviews. The checklist was used to analyse the included articles.

The characteristics of the 18 articles included in the study are presented in Table 2 . Ten (55.6%) were cross-sectional studies [ 2 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ], three (16.7%) were mixed methods studies [ 18 , 26 , 37 ], two (11.1%) were quasi-experimental and longitudinal studies [ 3 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], and one (5.5%) was a qualitative study [ 41 ].

The population involved in the study was a mix of students from various fields and departments, including medical, nursing, pharmacy, psychology, students taking management courses, and engineering students [ 3 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 38 , 39 , 41 ]. Other students were undergraduates from different fields that were not mentioned [ 2 , 10 , 26 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 ].

Study outcomes were categorized using three categories; student performance, student engagement, and studies that measured both student performance and engagement.

The summary of findings from the included studies are presented in Table 3 . Questionnaire surveys were mostly used across all the studies, however, one study used focus group discussions [ 41 ] and another study used a checklist to collect administrative data from student registers [ 40 ]. Study designs used in the included studies are cross-sectional, mixed methods, quasi-experimental, qualitative, and longitudinal. Studies were included from various countries across all six continents, countries in Asia constituted most of the studies (n = 7), Europe (n = 5), North America (n = 2), South America, Africa, and Australia all had one country represented in the study location.

3.1 Students’ performance

The impact of online learning on student performance was documented in thirteen studies [ 3 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. In the study conducted by Elnour et al. [ 12 ], about half of the respondents strongly agreed that online learning had a negative impact on their grades in comparison to when they were attending face-to-face classes, two other studies had similar findings where students reported a decline in their grades during online learning [ 34 , 40 ].

Two studies experimented to compare grades achieved by students taking online classes (experimental group) with students taking face-to-face classes (control group) and found that those in the experimental group scored higher during examinations than those in the control group [ 38 , 39 ]. Nine studies included in this review showed a positive impact of online learning on student performance [ 3 , 10 , 13 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 ] students reported getting higher scores during examinations when they switched to online learning.

Two studies measured the performance of students before online learning and during online learning [ 3 , 40 ]. Both studies had varying findings, one of the studies found that when students started learning online, their grades improved on average from 4.7/10 to 5.15/10 and dropped to 4.6/10 when they went back to face-to-face learning [ 3 ], while another study used students' registers to capture their grades before online learning and when they started studying online and found that the switch to online learning led to a lesser number of credits obtained by the students [ 40 ].

3.2 Students’ engagement

Student engagement during online learning was reported in ten of the reviewed articles [ 2 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 41 ]. Students reported the negative effect of online learning on engagement with their peers and teachers. Nonetheless, in one of the studies [ 18 ], the respondents reported that online learning did not affect engagement with their lecturers, even though they felt least engaged with their peers. Students reported the effect of isolation when they were studying and taking classes online in comparison to when they had face-to-face learning [ 2 , 41 ], they revealed that the abrupt switch did not allow them to understand and adapt to the new form of learning and it led to feelings of isolation and separation from their classmates and teachers [ 2 ]

For science-based courses, students reported concern about carrying out practical classes, as studying online did not grant them the opportunity to effectively carry out practical [ 18 ]. Also, medical students reported dissatisfaction in interacting with their patients, which led to less engagement and connection [ 13 ]. One of the studies reviewed stated the role of engagement in increasing student performance over time, students stated that when they interact and engage with their teams and lecturers, they tend to perform better in their examinations [ 18 ].

4 Discussion

This study aimed to examine the impact of online learning on students' academic performance and engagement. The results underscore the varied impacts of online learning on student performance and engagement. While some students benefited from the flexibility and new opportunities presented by online learning, others struggled with the lack of direct interaction and practical engagement. This suggests that while online learning has potential, it requires careful implementation and support to address the challenges of engagement and practical application, particularly in fields requiring hands-on experience.

Majority of the articles in this review showed that online learning did not negatively affect the academic performance of students, though the studies did not have a standardized method of measuring their performance before online learning and during studying online, most of the survey was based on the students' perceptions. These findings support the findings of other studies that reported an increase in students' grades when they studied online [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Possible reasons highlighted for the increase in performance include the availability of recorded videos; students were able to study and listen to past teachings at their own pace and review course content when necessary. This enabled them to manage their time better and strengthen their understanding of complex materials and courses. Also, the use of computers and the availability of good internet connectivity were major reasons emphasized by students in helping them achieve good grades. The incorporation of digital tools like interactive quizzes, recorded videos, and learning management systems (LMS) provided students an interesting avenue to learn, which enhanced their academic performance [ 45 ]. Many students found that independent learning was suitable and matched their unique learning style better than F2F learning, this could be another reason for the improvement in their grades.

Despite reporting good grades with online learning, students still felt unsatisfied with this mode of learning, they reported bad internet connectivity, especially in studies conducted in Africa and Asia [ 1 , 13 ]. Furthermore, there were no academic performance variations between rural and urban learners [ 46 ], this finding varied with the finding of Bacher et al. [ 47 ] who stated that students in rural communities will require more support to bridge the academic gap experienced with their peers who live in urban settings. Another author compared the impact of environmental conditions at home and student academic performance, and it was found that students who had poor lighting conditions or those who were exposed to noisy environments performed poorly, this suggests that online learners need proper indoor lighting, ventilation, and a quiet environment for proper learning [ 42 ]

However, one of the studies found that online learning reduced the academic grades of the students, this could be because of the use of smartphones in carrying out examinations instead of using computers, and inexperience with the use of the Learning Management System (LMS) [ 34 ].

A lot of implications can arise as a result of improved performance among students due to a shift from F2F to online learning platforms. For students, it can increase confidence and contentment [ 48 ], but because of the dependence on technology, students also need to learn time management skills and self-discipline [ 49 ] which are essential for success in an online environment. Families may feel less stressed about their children’s academic success, but this might also result in more pressure to sustain these outcomes [ 50 ], particularly if the progress is linked directly to online learning. More educated citizens will benefit from increased academic performance through an increase in rates of employment and economic growth [ 51 ], but unequal access to technology could make the divide between various socioeconomic classes more pronounced. Furthermore, improved student performance has the potential to elevate the overall quality of the workforce, accelerating economic growth and competitiveness in the global market [ 52 ]. However, disparities in online learning must be addressed to guarantee that every student has an equal chance of success.

In terms of student engagement, similar findings were seen across the reviewed articles, most students reported that online learning was less engaging, and they could not associate with their peers or lecturers which made them feel self-isolated. This finding has been supported by Hollister et al. [ 43 ] where students complained of less engagement in online classes despite attaining good grades, they missed the spontaneous conversations and collaborations that are typical in a classroom setting. Motivation is an important element in both online and offline learning, students need self-motivation for overall learning outcomes [ 44 ]. Findings from this review indicate that students who reported being able to engage with their teams and lecturers actively attribute their success to self-motivation. Also, Cents-Boonstra et al. [ 53 ] investigated the role of motivating teaching behaviour and found that teachers who offered support and guidance during learning had more student engagement in comparison to teachers who did not offer any support or show enthusiasm for teaching. Courses that previously required hands-on experiences, like clinical practice or laboratory work, was challenging to conduct online, medical students expressed dissatisfaction with not being able to conduct practical sessions in the laboratory or interact effectively with their patients, this made learning online an isolating experience. Their participation dropped as a result of the separation between the theoretical and practical components of their education. This supports the finding of Khalil et al. [ 54 ] where medical students stated that they missed having live clinical sessions and couldn’t wait to go back to having a F2F class. Major barriers to participation included a lack of personal devices, and, inconsistent internet access, especially in rural or low-income areas. These barriers made it difficult for students to participate fully in online classes and also made them feel more frustrated and disengaged. This is similar to a study by Al-Amin et al. [ 11 ] where tertiary students studying online complained of less engagement in classroom activities.

Generally, students reported a negative effect of online learning on their engagement. This could be a result of poor technology skills, unavailability of personal computers or smartphones, or lack of internet services [ 55 ].

In a study conducted by Heilporn et al. [ 56 ], the author examined strategies that can be used by teachers to improve student engagement in a blended learning environment. Presenting a clear course structure and working at a particular pace, engaging learners with interactive activities, and providing additional support and constant feedback will help in improving overall student engagement. In a study by Gopal et al. [ 57 ], it was found that quality of instructor and the ability to use technological tools is an important element in influencing students engagement. The instructor needs to understand the psychology of the students in order to effectively present the course material.

A decrease in student engagement can have a detrimental effect on their entire educational experience, this can affect motivation and satisfaction. In the long-term, this could lead to decreased academic achievement and increased dropout rates [ 58 ]. To maintain students' motivation and engagement, families might need to put in extra effort especially if they simultaneously manage the online learning needs of numerous children [ 59 ]. This can result in additional stress or financial constraints in purchasing technological tools. In addition, for students studying online, it results in a less unified learning environment, which may diminish community bonds, and instructors will find it difficult to assist disengaged and potentially falling behind students [ 60 ].

The contrast between positive student performance and negative student engagement suggests that while online learning is a useful approach, it is less successful at fostering the interactive and social aspects of education. Online learning must include interactive components like discussion boards, and group projects that will enable in-person communication [ 61 ]. Furthermore, it is essential to guarantee that students have access to sufficient technology tools and training to enable them participate fully.

Some learners found it difficult to give the benefits of learning online, but none failed to give the benefits of face-to-face learning. In a study by Aguilera-Hermida [ 6 ], college students preferred studying in a physical classroom against studying online, they also found it hard to adapt to online classes, this decreased their level of participation and engagement. Also, an increase in good grades might be a result of cheating behaviours [ 3 ], given that unlike face-to-face learning where teachers are present to invigilate and validate that examinations were individual-based, for online learning it is difficult to determine if examinations were truly carried out by the students, giving students the option to share their answers with classmates or obtain them from internet resources. The studies did not state if measures were put in place to ensure exams taken online were devoid of cheating by the students.

Furthermore, online learning is here to stay, but there is a need for planning and execution of the process to mitigate the issue of students engaging effectively. Ignorance of this could put the possible advantages of this process in danger [ 62 ].

4.1 Limitations

A major limitation of this systematic review is the paucity of studies that objectively measured performance and engagement in students before and after the introduction of online learning. Findings in fourteen (78%) of the included articles were self-reported by the students which could lead to recall and/or desirability bias. In addition, the lack of uniform measurement or scale for assessing students’ performance and engagement is also a limitation. Subsequently, we suggest that standardized study tools should be developed and validated across various populations to more accurately and objectively evaluate the impact of the introduction of online learning on students’ performance and engagement. More studies should be conducted with clear pre- and post-intervention measurements using different pedagogical approaches to access their effects on students’ performance and engagement. These studies should also design ways of measuring indicators objectively without recall or desirability biases. Furthermore, the exclusion of studies that are not open access as well as publication bias for articles not published in English language are also limitations of this study.

5 Conclusion

The switch to online learning had both its advantages and disadvantages. The flexibility and accessibility of online platforms have played a major role in the enhancement of student performance, yet the decline in engagement underscores the need for more efficacious strategies to promote engagement. Online learning had a positive impact on student performance, most of the students reported either an increase or no change in grades when they changed to learning online. Only three studies stated a decline in student performance. Overall, students felt with online learning, they could not engage with their peers, teams, and teachers. They had a feeling of social isolation and felt more engagement would have improved their performance better. Schools and policymakers must develop strategies to mitigate the challenge of student engagement in online learning. This is necessary to prepare institutions for potential future pandemics which will compel reliance on online learning, this is critical for maintaining student satisfaction and overall learning outcomes.

In summary, online learning has the capacity to enhance academic achievement, but its effectiveness depends on effectively resolving the barriers associated with student involvement. Future studies should examine the long-term effects of online learning on student's performance and engagement with emphasis on creating strategies to improve the social and interactive components of the learning process. This is essential to guarantee that, in the future, online learning will be a viable and productive educational medium not just a band-aid fix during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The articles used for this systematic review are all cited and publicly available.

Bossman A, Agyei SK. Technology and instructor dimensions, e-learning satisfaction, and academic performance of distance students in Ghana. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):09200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E09200 .

Article Google Scholar

Rahman A, Islam MS, Ahmed NAMF, Islam MM. Students’ perceptions of online learning in higher secondary education in Bangladesh during COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Human Open. 2023;8(1):100646. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2023.100646 .

Pérez MA, Tiemann P, Urrejola-Contreras GP. The impact of the learning environment sudden shifts on students’ performance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ Méd. 2023;24(3):100801. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EDUMED.2023.100801 .

Basar ZM, Mansor AN, Jamaludin KA, Alias BS. The effectiveness and challenges of online learning for secondary school students—a case study. Asian J Univ Educ. 2021;17(3):119–29.

Rajabalee YB, Santally MI. Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2021;26(3):2623–56.

Aguilera-Hermida AP. College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. Int J Educ Res Open. 2020;1:100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011 .

Nambiar D. The impact of online learning during COVID-19: students’ and teachers’ perspective. Int J Indian Psychol. 2020;8(2):783–93.

Google Scholar

Maheshwari M, Gupta AK, Goyal S. Transformation in higher education through e-learning: a shifting paradigm. Pac Bus Rev Int. 2021;13(8):49–63.

Pokhrel S, Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High Educ Future. 2021;8(1):133–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631120983481 .

Kedia P, Mishra L. Exploring the factors influencing the effectiveness of online learning: a study on college students. Soc Sci Human Open. 2023;8(1):100559. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2023.100559 .

Al-Amin M, Al Zubayer A, Deb B, Hasan M. Status of tertiary level online class in Bangladesh: students’ response on preparedness, participation and classroom activities. Heliyon. 2021;7(1):e05943. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2021.E05943 .

Elnour AA, Abou Hajal A, Goaddar R, Elsharkawy N, Mousa S, Dabbagh N, Mohamad Al Qahtani M, Al Balooshi S, Othman Al Damook N, Sadeq A. Exploring the pharmacy students’ perspectives on off-campus online learning experiences amid COVID-19 crises: a cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(7):1339–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.05.024 .

Fahim A, Rana S, Haider I, Jalil V, Atif S, Shakeel S, Sethi A. From text to e-text: perceptions of medical, dental and allied students about e-learning. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12157. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E12157 .

Henriksen D, Creely E, Henderson M. Folk pedagogies for teacher transitions: approaches to synchronous online learning in the wake of COVID-19. J Technol Teach Educ. 2020;28(2):201–9.

Zhu X, Chen B, Avadhanam RM, Shui H, Zhang RZ. Reading and connecting: using social annotation in online classes. Inf Learn Sci. 2020;121(5/6):261–71.

Bao W. COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: a case study of Peking University. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2020;2(2):113–5.

Baber H. Determinants of students’ perceived learning outcome and satisfaction in online learning during the pandemic of COVID-19. J Educ Elearn Res. 2020;7(3):285–92.

Afzal F, Crawford L. Student’s perception of engagement in online project management education and its impact on performance: the mediating role of self-motivation. Proj Leadersh Soc. 2022;3:100057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2022.100057 .

Paul J, Jefferson F. A comparative analysis of student performance in an online vs. face-to-face environmental science course from 2009 to 2016. Front Comput Sci. 2019;1:7.

Francescucci A, Rohani L. Exclusively synchronous online (VIRI) learning: the impact on student performance and engagement outcomes. J Mark Educ. 2019;41(1):60–9.

Pei L, Wu H. Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1666538.

Thang SM, Mahmud N, Mohd Jaafar N, Ng LLS, Abdul Aziz NB. Online learning engagement among Malaysian primary school students during the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Innov Creat Change. 2022;16(2):302–26.

Ribeiro L, Rosário P, Núñez JC, Gaeta M, Fuentes S. “First-year students background and academic achievement: the mediating role of student engagement. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2669.

Muzammil M, Sutawijaya A, Harsasi M. Investigating student satisfaction in online learning: the role of student interaction and engagement in distance learning university. Turk Online J Distance Educ. 2020;21(Special Issue-IODL):88–96.

Mandasari B. The impact of online learning toward students’ academic performance on business correspondence course. EDUTEC. 2020;4(1):98–110.

Chen LH. Moving forward: international students’ perspectives of online learning experience during the pandemic. Int J Educ Res Open. 2023;5:100276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2023.100276 .

Wu YH, Chiang CP. Online or physical class for histology course: Which one is better? J Dent Sci. 2023;18(3):1295–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2023.03.004 .

Salahshouri A, Eslami K, Boostani H, Zahiri M, Jahani S, Arjmand R, Heydarabadi AB, Dehaghi BF. The university students’ viewpoints on e-learning system during COVID-19 pandemic: the case of Iran. Heliyon. 2022;8(2):e08984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08984 .

Maqbool S, Farhan M, Abu Safian H, Zulqarnain I, Asif H, Noor Z, Yavari M, Saeed S, Abbas K, Basit J, Ur Rehman ME. Student’s perception of E-learning during COVID-19 pandemic and its positive and negative learning outcomes among medical students: a country-wise study conducted in Pakistan and Iran. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;82:104713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104713 .

Anderson T. Theories for learning with emerging technologies. In: Veletsianos G, editor. Emerging technologies in distance education. Athabasca: Athabasca University Press; 2010.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 .

Weerarathna RS, Rathnayake NM, Pathirana UPGY, Weerasinghe DSH, Biyanwila DSP, Bogahage SD. Effect of E-learning on management undergraduates’ academic success during COVID-19: a study at non-state Universities in Sri Lanka. Heliyon. 2023;9(9):e19293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19293 .

Bossman A, Agyei SK. Technology and instructor dimensions, e-learning satisfaction, and academic performance of distance students in Ghana. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):e09200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E09200 .

Mushtaha E, Abu Dabous S, Alsyouf I, Ahmed A, Raafat AN. The challenges and opportunities of online learning and teaching at engineering and theoretical colleges during the pandemic. Ain Shams Eng J. 2022;13(6):101770. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ASEJ.2022.101770 .

Wester ER, Walsh LL, Arango-Caro S, Callis-Duehl KL. Student engagement declines in STEM undergraduates during COVID-19–driven remote learning. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2021;22(1):22.1.50. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v22i1.2385 .

Lemay DJ, Bazelais P, Doleck T. Transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2021;4:100130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100130 .

Briggs MA, Thornton C, McIver VJ, Rumbold PLS, Peart DJ. Investigation into the transition to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, between new and continuing undergraduate students. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ. 2023;32:100430. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHLSTE.2023.100430 .

Nácher MJ, Badenes-Ribera L, Torrijos C, Ballesteros MA, Cebadera E. The effectiveness of the GoKoan e-learning platform in improving university students’ academic performance. Stud Educ Eval. 2021;70:101026. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.STUEDUC.2021.101026 .

Grønlien HK, Christoffersen TE, Ringstad Ø, Andreassen M, Lugo RG. A blended learning teaching strategy strengthens the nursing students’ performance and self-reported learning outcome achievement in an anatomy, physiology and biochemistry course—a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;52:103046. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEPR.2021.103046 .

De Paola M, Gioia F, Scoppa V. Online teaching, procrastination and student achievement. Econ Educ Rev. 2023;94:102378. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONEDUREV.2023.102378 .

Goodwin J, Kilty C, Kelly P, O’Donovan A, White S, O’Malley M. Undergraduate student nurses’ views of online learning. Teach Learn Nurs. 2022;17(4):398–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TELN.2022.02.005 .

Realyvásquez-Vargas A, Maldonado-Macías AA, Arredondo-Soto KC, Baez-Lopez Y, Carrillo-Gutiérrez T, Hernández-Escobedo G. The impact of environmental factors on academic performance of university students taking online classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):9194.

Hollister B, Nair P, Hill-Lindsay S, Chukoskie L. Engagement in online learning: student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Front Educ. 2022;7:851019. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.851019 .

Hsu HC, Wang CV, Levesque-Bristol C. Reexamining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Educ Inf Technol. 2019;24(3):2159–74.

Bradley VM. Learning Management System (LMS) use with online instruction. Int J Technol Educ. 2021;4(1):68–92.

Clark AE, Nong H, Zhu H, Zhu R. Compensating for academic loss: online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Econ Rev. 2021;68:101629.

Bacher-Hicks A, Goodman J, Mulhern C. Inequality in household adaptation to schooling shocks: Covid-induced online learning engagement in real time. J Public Econ. 2021;193:1043451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104345 .

Liu YM, Hou YC. Effect of multi-disciplinary teaching on learning satisfaction, self-confidence level and learning performance in the nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;55:103128.

Gelles LA, Lord SM, Hoople GD, Chen DA, Mejia JA. Compassionate flexibility and self-discipline: Student adaptation to emergency remote teaching in an integrated engineering energy course during COVID-19. Educ Sci (Basel). 2020;10(11):304.

Deng Y, et al. Family and academic stress and their impact on students’ depression level and academic performance. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:869337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869337 .

Gunderson M, Oreopolous P. Returns to education in developed countries. In: The economics of education; 2020. p. 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00003-3 .

Prasetyo PE, Kistanti NR. Human capital, institutional economics and entrepreneurship as a driver for quality & sustainable economic growth. Entrep Sustain Issues. 2020;7(4):2575. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.7.4(1) .

Cents-Boonstra M, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, Denessen E, Aelterman N, Haerens L. Fostering student engagement with motivating teaching: an observation study of teacher and student behaviours. Res Pap Educ. 2021;36(6):754–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1767184 .

Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, et al. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z .

Werang BR, Leba SMR. Factors affecting student engagement in online teaching and learning: a qualitative case study. Qualitative Report. 2022;27(2):555–77. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5165 .

Heilporn G, Lakhal S, Bélisle M. An examination of teachers’ strategies to foster student engagement in blended learning in higher education. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2021;18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00260-3 .