An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-.

Endotext [Internet].

- www.endotext.org

Definitions, Classification, and Epidemiology of Obesity

Jonathan Q. Purnell , MD.

Last Update: May 4, 2023 .

Recent research has established the physiology of weight regulation, the pathophysiology that leads to unwanted weight gain with establishment of a higher body-weight set point, and the defense of the overweight and obese state even when reasonable attempts in lifestyle improvement are made. This knowledge has informed our approach to obesity as a chronic disease. The assessment of adiposity risk for the foreseeable future will continue to rely on cost-effective and easily available measures of height, weight, and waist circumference. This risk assessment then informs implementation of appropriate treatment plans and weight management goals. Within the United States, prevalence rates for generalized obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m 2 ), extreme obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m 2 ), and central obesity continue to rise in children and adults with peak obesity rates occurring in the 5 th -6 th decades. Women may have equal or greater obesity rates than men depending on race, but less central obesity than men. Obesity disproportionately affects people by race and ethnicity, with the highest prevalence rates reported in Black women and Hispanic men and women. Increasing obesity rates in youth (ages 2-19 years) are especially concerning. This trend will likely continue to fuel the global obesity epidemic for decades to come, worsening population health, creating infrastructural challenges as countries attempt to meet the additional health-care demands, and greatly increasing health-care expenditures world-wide. To meet this challenge, societal and economic innovations will be necessary that focus on strategies to prevent further increases in overweight and obesity rates. For complete coverage of all related areas of Endocrinology, please visit our on-line FREE web-text, WWW.ENDOTEXT.ORG .

- INTRODUCTION

Unwanted weight gain leading to overweight and obesity has become a significant driver of the global rise in chronic, non-communicable diseases and is itself now considered a chronic disease. Because of the psychological and social stigmata that accompany developing overweight and obesity, those affected by these conditions are also vulnerable to discrimination in their personal and work lives, low self-esteem, and depression ( 1 ). These medical and psychological sequelae of obesity contribute to a major share of health-care expenditures and generate additional economic costs through loss of worker productivity, increased disability, and premature loss of life ( 2 - 4 ).

The recognition that being overweight or having obesity is a chronic disease and not simply due to poor self-control or a lack of will power comes from the past 70 years of research that has been steadily gaining insight into the physiology that governs body weight (homeostatic mechanisms involved in sensing and adapting to changes in the body’s internal metabolism, food availability, and activity levels so as to maintain fat content and body weight stability), the pathophysiology that leads to unwanted weight gain maintenance, and the roles that excess weight and fat maldistribution (adiposity) play in contributing to diabetes, dyslipidemia, heart disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and many other chronic diseases ( 5 , 6 ).

Expression of overweight and obesity results from an interaction between an individual’s genetic predisposition to weight gain and environmental influences. Gene discovery in the field of weight regulation and obesity has identified several major monogenic defects resulting in hyperphagia accompanied by severe and early-onset obesity ( 7 ) as well as many more minor genes with more variable impact on weight and fat distribution, including age-of-onset and severity. Several of these major obesity genes now have a specific medication approved to treat affected individuals ( 8 ). However, currently known major and minor genes explain only a small portion of body weight variations in the population ( 7 ). Environmental contributors to obesity have also been identified ( 9 ) but countering these will likely require initiatives that fall far outside of the discussions taking place in the office setting between patient and provider since they involve making major societal changes regarding food quality and availability, work-related and leisure-time activities, and social and health determinants including disparities in socio-economic status, race, and gender.

Novel discoveries in the fields of neuroendocrine ( 6 ) and gastrointestinal control ( 10 ) of appetite and energy expenditure have led to an emerging portfolio of medications that, when added to behavioral and lifestyle improvements, can help restore appetite control and allow modest weight loss maintenance ( 8 ). They have also led to novel mechanisms that help to explain the superior outcomes, both in terms of meaningful and sustained weight loss as well as improvements or resolution of co-morbid conditions, following metabolic-bariatric procedures such as laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass ( 11 , 12 ).

Subsequent chapters in this section of Endotext will delve more deeply into these determinants and scientific advances, providing a greater breadth of information regarding mechanisms, clinical manifestations, treatment options, and prevention strategies for those with overweight or obesity.

- DEFINITION OF OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY

Overweight and obesity occur when excess fat accumulation (globally, regionally, and in organs as ectopic lipids) increases risk for adverse health outcomes . Like other chronic diseases, this definition does not require manifistation of an obesity-related complication, simply that the risk for one is increased. This allows for implementation of weight management strategies targeting treatment and prevention of these related conditions. It is important to point out that thresholds of excess adiposity can occur at different body weights and fat distributions depending on the person or population being referenced.

Ideally, an obesity classification system would be based on a practical measurement widely available to providers regardless of their setting, would accurately predict health risk (prognosis), and could be used to assign treatment stategies and goals. The most accurate measures of body fat adiposity such as underwater weighing, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning, computed tomograpy (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are impractical for use in everyday clinical encounters. Estimates of body fat, including body mass index (BMI, calculated by dividing the body weight in kilograms by height in meters squared) and waist circumference, have limitations compared to these imaging methods, but still provide relevant information and are easily obtained in a variety of practice settings.

It is worth pointing out two important caveats regarding cuurent thresholds used to diagnose overweight and obesity. The first is that although we favor the assignement of specific BMI cut-offs and increasing risk ( Table 1 ), relationships between body weight or fat distribution and conditions that impair health actually represent a continum. For example, increased risk for type 2 diabetes and premature mortality occur well below a BMI of 30 kg/m 2 (the threshold to define obesity in populations of European extraction) ( 13 ). It is in these earlier stages that preventative strategies to limit further weight gain and/or allow weight loss will have their greatest health benefits. The second is that historic relationships between increasing BMI thresholds and the precense and severity of co-morbidities have been disrupted as better treatments for obesity-complications become available. For example, in the past several decades, atherosclerotic cardiovascular (ASCVD) mortality has steadily declined in the US population ( 14 ) even as obesity rates have risen (see below). Although it is generally accepted that this decline in ASCVD deaths is due to better care outside the hospital during a coronary event (e.g., better coordination of “first responders” services such as ambulances and more widespread use by the public of cardiopulmonary resusitation and defibrillator units), advances in intensive care, smoking cessation, and in the office (increased use of aspirin, statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, and blood pressure medications) ( 15 ), these data have also been cited to support the claim that being overweight might actually protect against heart disease ( 16 ). In this regard, updated epidemiological data on the health outcomes related to being overweight or having obesity should include not just data on morbidity and mortality, but also health care metrics such as utilization and costs, medications used, and the number of treatment-related procedures performed.

- CLASSIFICATION OF OVERWEIGHT, OBESITY, AND CENTRAL OBESITY

Fat Mass and Percent Body Fat

Fat mass can be directly measured by one of several imaging modalities, including DEXA, CT, and MRI, but these systems are impractical and cost prohibitive for general clinical use. Instead, they are mostly used for research. Fat mass can be measured indirectly using water (underwater weighing) or air displacement (BODPOD), or bioimpedance analysis (BIA). Each of these methods estimates the proportion of fat or non-fat mass and allows calcutation of percent body fat. Of these, BODPOD and BIA are often offered through fitness centers and clinics run by obesity medicine specialists. However, their general use in the care of patients who are overweight and with obesity is still limited. Interpretation of results from these procedures may be confounded by common conditions that accompany obesity, especially when fluid status is altered such as in congenstive heart failure, liver disease, or chronic kidney disease. Also, ranges for normal and abnormal are not well established for these methods and, in practical terms, knowing them will not change current recommendations to help patients achieve sustained weight loss.

Body Mass Index

Body mass index allows comparison of weights independently of stature across populations. Except in persons who have increased lean weight as a result of intense exercise or resistance training (e.g., bodybuilders), BMI correlates well with percentage of body fat, although this relationship is independently influenced by sex, age, and race ( 17 ). This is especially true for South Asians in whom evidence suggests that BMI-adjusted percent body fat is greater than other populations ( 18 ). In the United States, data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II) were used to define obesity in adults as a BMI of 27.3 kg/m 2 or more for women and a BMI of 27.8 kg/m 2 or more for men ( 19 ). These definitions were based on the gender-specific 85 th percentile values of BMI for persons 20 to 29 years of age. In 1998, however, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) classification for overweight and obesity ( Table 1 ) ( 20 ). The WHO classification, which predominantly applied to people of European ancestry, assigns increasing risk for comorbid conditions—including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease—to persons with higher a BMI relative to persons of normal weight (BMI of 18.5 - 25 kg/m 2 ) ( Table 1 ). However, Asian populations are known to be at increased risk for diabetes and hypertension at lower BMI ranges than those for non-Asian groups due largely to predominance of central fat distribution and higer percentage fat mass (see below). Consequently, the WHO has suggested lower cutoff points for consideration of therapeutic intervention in Asians: a BMI of 18.5 to 23 kg/m 2 represents acceptable risk, 23 to 27.5 kg/m 2 confers increased risk, and 27.5 kg/m 2 or higher represents high risk ( 21 , 22 ).

Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risk. Adapted from reference ( 20 ).

View in own window

Disease risk for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Increased waist circumference can also be a marker for increased risk even in persons of normal weight.

Fat Distribution (Central Obesity)

In addition to an increase in total body weight, a proportionally greater amount of fat in the abdomen or trunk compared with the hips and lower extremities has been associated with increased risk for metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and heart disease in both men and women ( 23 , 24 ). Abdominal obesity is commonly reported as a waist-to-hip ratio, but it is most easily quantified by a single circumferential measurement obtained at the level of the superior iliac crest ( 20 ). For the practioner, waist circumference should be measured in a standardized way ( 20 ) at each patient’s visit along with body weight. The original US national guidelines on overweight and obesity categorized men at increased relative risk for co-morbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease if they have a waist circumference greater than 102 cm (40 inches) and women if their waist circumference exceeds 88 cm (35 inches) ( Table 1 ) ( 20 ). These waist circumference thresholds are also used to define the “metabolic syndrome” by the most recent guidelines from the American Heart Association and the National Lipid Association (e.g., triglyceride levels > 150 mg/dL, hypertension, elevated fasting glucose (100 – 125 mg/dL)) or prediabetes (hemoglobin A1c between 5.7 and 6.4%) ( 25 , 26 ). Thus, an overweight person with predominantly abdominal fat accumulation would be considered “high” risk for these diseases even if that person does not meet BMI criteria for obesity. Such persons would have “central obesity.” It is commonly accepted that the predictive value for increased health risk by waist circumference is in patients at lower BMI’s (< 35 kg/m 2 ) since those with class 2 obesity or higher will nearly universally have waist circumferences that exceed disease risk cut-offs.

However, the relationships between central adiposity with co-morbidities are also a continuum and vary by race and ethnicity. For example, in those of Asian descent, abdominal (central) obesity has long been recognized to be a better disease risk predictor than BMI, especially for type 2 diabetes ( 27 ). As endorsed by the International Diabetes Federation ( 28 ) and summarized in a WHO report in 2008 ( 29 ), different countries and health organizations have adopted differing sex- and population-specific cut offs for waist circumference thresholds predictive of increased comorbidity risk. In addition to the US criteria, alternative thresholds for central obesity as measured by waist circumference include > 94 cm (37 inches) and > 80 cm (31.5 inches) for men and women of European anscestry and > 90 cm (35.5 inches) and > 80 cm (31.5 inches) for men and women of South Asian, Japanese, and Chinese origin ( 28 , 29 ), respectively.

- EPIDEMIOLOGY OF OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY IN THE UNITED STATES

In the United States (US), data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey using measured heights and weights shows that the steady increase in obesity prevalence in both children and adults over the past several decades has not waned, although there are exceptions among subpopulations as described in greater detail below. In the most recently published US report (2017-2020), 42.4% of adults (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m 2 ) ( 30 ) and 20.9% of youth (BMI ≥ 95 th percentile of age- and sex-specific growth charts) ( 31 ) have obesity, and the age-adjusted prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m 2 ) was 9.2% ( 30 ) ( Figure 1 ).

Trends in age-adjusted obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m 2 ) and severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m 2 ) prevalence among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1999–2000 through 2017–2018. Taken from reference ( 30 ).

Obesity and Severe Obesity in Adults: Relationships with Age, Sex, and Demographics

Age-Adjusted Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity in US Adults. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, prevalence estimates are weighted and age-adjusted to the projected 2000 Census population using age groups 20-39, 40-59, and 60 or older. Significant linear trends (P < .001) for all groups except for obesity among non-Hispanic Black men, which increased from 1999-2000 to 2005-2006 and then leveled after 2005-2006. Data taken from reference ( 31 ).

On average, the obesity rate in US adults has nearly tripled since the 1960’s (Reference ( 32 ) and Figure 2 ). These large increases in the number of people with obesity and severe obesity, while at the same time the level of overweight has remained steady ( 32 , 33 ), suggests that the “obesogenic” environment is disproportionately affecting those portions of the population with the greatest genetic potential for weight gain ( 34 ). This currently leaves slightly less than 30% of the US adult population as having a healthy weight (BMI between 18.5 and 25 kg/m 2 ).

Men and women now have similar rates of obesity and the peak rates of obesity for both men and women in the US occur between the ages of 40 and 60 years ( Figures 2 and 3 ). In studies that have measured body composition, fat mass also peaks just past middle age in both men and women, but percent body fat continues to increase past this age, particularly in men because of a proportionally greater loss in lean mass ( 35 - 37 ). The menopausal period has also been associated with an increase in percent body fat and propensity for central (visceral) fat distribution, even though total body weight may change very little during this time ( 38 - 41 ).

The rise in obesity prevalence rates has disproportionately affected US minority populations ( Figure 2 ). The highest prevelance rates of obesity by race and ethnicity are currently reported in Black women, native americans, and Hispanics ( Figure 2 and reference ( 42 )). In general, women and men who did not go to college were more likely to have obesity than those who did, but for both groups these relationships varied depending on race and ethnicity (see below). Amongst women, obesity prevelance rates decreased with increasing income in women (from 45.2% to 29.7%), but there was no difference in obesity prevalence between the lowest (31.5%) and highest (32.6%) income groups among men ( 43 ).

Prevalence of obesity among adults aged 20 and over, by sex and age: United States, 2017–2018. Taken from reference ( 30 ).

The interactions of socieconomic status and obesity rates varied based on race and ethnicity ( 43 ). For example, the expected inverse relationship between obesity and income group did not hold for non-Hispanic Black men and women in whom obesity prevelance was actually higher in the highest compared to lowest income group (men) or showed no relationship to income by racial group at all (women) ( 43 ). Obesity prevalence was lower among college graduates than among persons with less education for non-Hispanic White women and men, Black women, and Hispanic women, but not for Black and Hispanic men. Asian men and women have the lowest obesity prevelance rates, which did not vary by eduction or income level ( 43 ).

Central Obesity

As discussed above, central weight distribution occurs more commonly in men than women and increases in both men and women with age. In one of the few datasets that have published time-trends in waist circumference, it has been shown that over the past 20 years, age-adjusted waist circumferences have tracked upward in both US men and women ( Figure 4 ). Much of this likely reflects the population increases in obesity prevelance since increasing fat mass and visceral fat track together ( 52 ).

Age-adjusted mean waist circumference among adults in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2012. Adapted from ( 51 ).

Childhood obesity is a risk factor for adulthood obesity ( 44 - 46 ). In this regard, the similar tripling of obesity rates in US youth (ages 2-19 years old) ( Figure 5 ) to 20.9% in 2018 ( 31 ) is worrisome and will contribute to the already dismal projections of the US adult population approaching 50% obesity prevelance by the year 2030 ( 47 ). Obesity prevalence was 26.2% among Hispanic children, 24.8% among non-Hispanic Black children, 16.6% among non-Hispanic White children, and 9.0% among non-Hispanic Asian children ( 48 ). Like adults, obesity rates in children are greater when they are live in households with lower incomes and less education of the head of the household ( 49 ). In this regard, these obesity gaps have been steadily widening in girls, whereas the differences between boys has been relatively stable ( 49 ).

Trends in obesity among children and adolescents aged 2–19 years, by age: United States, 1963–1965 through 2017–2018. Obesity is defined as body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to the 95th percentile from the sex-specific BMI-for-age 2000 CDC Growth Charts. Taken from reference ( 50 ).

With regard to socieconomic status, the inverse trends for lower obesity rates and higher income and education (of households) held in all race and ethnic origin groups with the following exceptions: obesity prevalence was lower in the highest income group only in Hispanic and Asian boys and did not differ by income among non-Hispanic Black girls ( 49 ).

- INTERNATIONAL TRENDS IN OBESITY

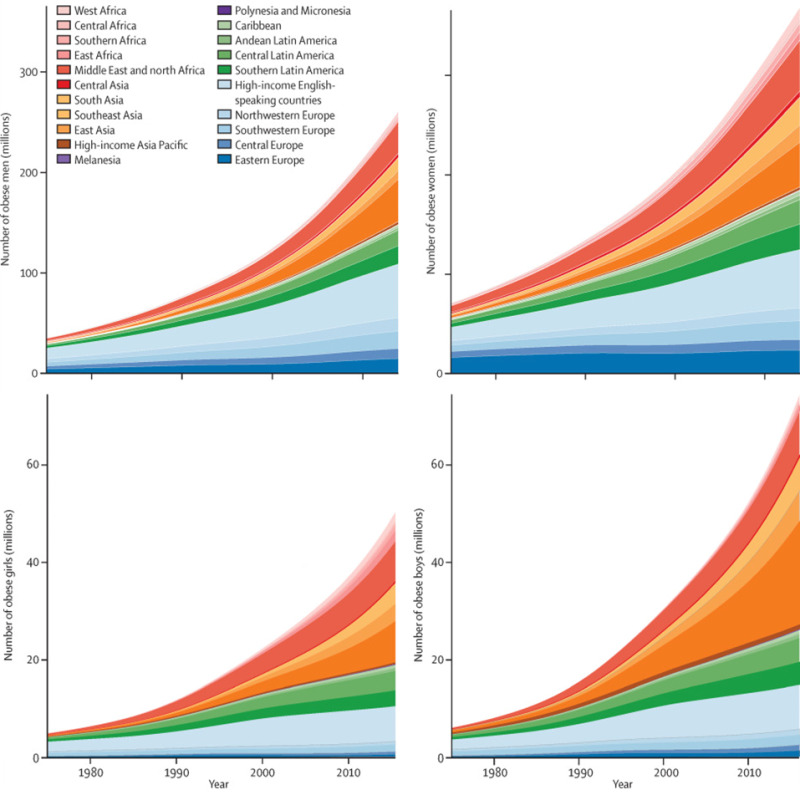

Historically, international obesity rates have been lower than in the US, and most developing countries considered undernutrition to be their topmost health priority ( 53 ). However, international rates of overweight and obesity have been rising steadily for the past several decades and, in many countries, are now meeting or exceeding those of the US ( Figure 6 ) ( 54 , 55 ). In 2016, 1.3 billion adults were overweight worldwide and, between 1975 to 2016, the number of adults with obesity increased over six-fold, from 100 million to 671 million (69 to 390 million women, 31 to 281 million men) ( 54 ). Especially worrisome have been similar trends in the youth around the world ( Figure 6 ), from 5 million girls and 6 million boys with obesity in 1975 to 50 million girls and 74 million boys in 2016 ( 54 ), as this means the rise in obesity rates will continue for decades as they mature into adults.

The growth in the wordwide prelance of overweight and obesity is thought to be primarily driven by economic and technological advancements in all developing societies ( 56 , 57 ). These forces have been ongoing in the US and other Western countries for many decards but are being experienced by many developing countries on a compressed timescale. Greater worker productivity in advancing economies means more time spent in sedentary work (less in manual labor) and less time spent in leisure activity. Greater wealth allows the purchase of televisions, cars, processed foods, and more meals eaten out of the house, all of which have been associated with greater rates of obesity in children and adults. More details and greater discussion of these issues can be found in Endotext Chapters on Non-excercise Activity Thermogenesis ( 58 ) and Obesity and the Environment ( 9 ).

Regardless of the causes, these trends in global weight gain and obesity are quickly creating a tremendous burden on health-care systems and cost to countries attempting to respond to the increased treatment demands ( 59 ). They are also feuling a rise in global morbity and mortality for chronic (non-communicable) diseases, especially for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and especially in Asian and South Asian populations where rates of type 2 diabetes are currently exploding ( 15 , 60 - 63 ). Efforts need to be made to deliver adequate health care to those currently with obesity and, at the same time, find innovative and alternative solutions that allow economies to prosper and to incorporate technologies that will reverse current trends in obesity and obesity-related complications.

Trends in the number of adults, children, and adolescents with obesity and with moderate and severe underweight by region. Children and adolescents were aged 5–19 years. (Taken from ( 54 )).

Obesity is both a chronic disease in its own right and a primary contributor to other leading chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases. In the clinic, obesity is still best defined using commonly available tools, including BMI and waist circumference; although it is hoped that newer imaging modalities allowing more precise quantification of amount and distribution of excess lipid depots will improve obesity risk assessment. The general rise in obesity taking place in the US over the past 50 years is now occurring globally. In the US, the prevalence rates of obesity in adult men and women are now similar at 40%, and minorities are disproportionately affected, including Blacks, Native Americans, and Hispanics, with obesity rates of 50% or higher. Particularly worrisome is the global increase in obesity prevalence in children and adolescents as these groups will continue to contribute to a rising adult obesity rates for several decades to come. As important as finding solutions that address the global logistical and financial challenges facing health-care systems attempting to meet current demands of obesity and weight-related co-morbidities will be finding innovative solutions that prevent and reverse current population weight gain trends.

This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) license. A copy of the license can be viewed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ .

- Cite this Page Purnell JQ. Definitions, Classification, and Epidemiology of Obesity. [Updated 2023 May 4]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-.

In this Page

Links to www.endotext.org.

- View this chapter in Endotext.org

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- The effectiveness of web-based programs on the reduction of childhood obesity in school-aged children: A systematic review. [JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012] The effectiveness of web-based programs on the reduction of childhood obesity in school-aged children: A systematic review. Antwi F, Fazylova N, Garcon MC, Lopez L, Rubiano R, Slyer JT. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012; 10(42 Suppl):1-14.

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022] Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1; 2(2022). Epub 2022 Feb 1.

- Review Screening and Interventions for Childhood Overweight [ 2005] Review Screening and Interventions for Childhood Overweight Whitlock EP, Williams SB, Gold R, Smith P, Shipman S. 2005 Jul

- Review Body Weight Regulation. [Endotext. 2000] Review Body Weight Regulation. Woolf EK, Cabre HE, Niclou AN, Redman LM. Endotext. 2000

- Trends in Adiposity and Food Insecurity Among US Adults. [JAMA Netw Open. 2020] Trends in Adiposity and Food Insecurity Among US Adults. Myers CA, Mire EF, Katzmarzyk PT. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Aug 3; 3(8):e2012767. Epub 2020 Aug 3.

Recent Activity

- Definitions, Classification, and Epidemiology of Obesity - Endotext Definitions, Classification, and Epidemiology of Obesity - Endotext

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- For educators

- English (US)

- English (India)

- English (UK)

- Greek Alphabet

This problem has been solved!

You'll get a detailed solution from a subject matter expert that helps you learn core concepts.

Question: Research studies on obesity and healthcare have found that _________.Most nurses understand that obesity can be easily prevented by self-control.Overweight people are less likely to receive preventive care than others.Medical professionals do not hold the same negative perceptions that employers hold about those who are overweight.The attitude of medical

Research studies on obesity and healthcare have found that ____:

This is an incomplete statement, and...

Not the question you’re looking for?

Post any question and get expert help quickly.

- Open access

- Published: 15 August 2018

How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health

- A. Janet Tomiyama 1 ,

- Deborah Carr 2 ,

- Ellen M. Granberg 3 ,

- Brenda Major 4 ,

- Eric Robinson 5 ,

- Angelina R. Sutin 6 &

- Alexandra Brewis 7

BMC Medicine volume 16 , Article number: 123 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

150k Accesses

377 Citations

1605 Altmetric

Metrics details

In an era when obesity prevalence is high throughout much of the world, there is a correspondingly pervasive and strong culture of weight stigma. For example, representative studies show that some forms of weight discrimination are more prevalent even than discrimination based on race or ethnicity.

In this Opinion article, we review compelling evidence that weight stigma is harmful to health, over and above objective body mass index. Weight stigma is prospectively related to heightened mortality and other chronic diseases and conditions. Most ironically, it actually begets heightened risk of obesity through multiple obesogenic pathways. Weight stigma is particularly prevalent and detrimental in healthcare settings, with documented high levels of ‘anti-fat’ bias in healthcare providers, patients with obesity receiving poorer care and having worse outcomes, and medical students with obesity reporting high levels of alcohol and substance use to cope with internalized weight stigma. In terms of solutions, the most effective and ethical approaches should be aimed at changing the behaviors and attitudes of those who stigmatize, rather than towards the targets of weight stigma. Medical training must address weight bias, training healthcare professionals about how it is perpetuated and on its potentially harmful effects on their patients.

Weight stigma is likely to drive weight gain and poor health and thus should be eradicated. This effort can begin by training compassionate and knowledgeable healthcare providers who will deliver better care and ultimately lessen the negative effects of weight stigma.

Peer Review reports

In a classic study performed in the late 1950s, 10- and 11-year-olds were shown six images of children and asked to rank them in the order of which child they ‘liked best’. The six images included a ‘normal’ weight child, an ‘obese’ child, a child in a wheelchair, one with crutches and a leg brace, one with a missing hand, and another with a facial disfigurement. Across six samples of varying social, economic, and racial/ethnic backgrounds from across the United States, the child with obesity was ranked last [ 1 ].

In the decades since, body weight stigma has spread and deepened globally [ 2 , 3 ]. We define weight stigma as the social rejection and devaluation that accrues to those who do not comply with prevailing social norms of adequate body weight and shape. This stigma is pervasive [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]; for example, in the United States, people with greater body mass index (BMI) report higher rates of discrimination because of their weight compared to reports of racial discrimination of ethnic minorities in some domains [ 7 ]. Women are particularly stigmatized due to their weight across multiple sectors, including employment, education, media, and romantic relationships, among others [ 8 ]. Importantly, weight stigma is also pervasive in healthcare settings [ 9 ], and has been observed among physicians, nurses, medical students, and dietitians [ 4 ]. Herein, we first address the obesogenic and health-harming nature of weight stigma, and then provide a discussion of weight stigma specifically in healthcare settings. We conclude with potential strategies to help eradicate weight stigma.

Weight stigma triggers obesogenic processes

Common wisdom and certain medical ethicists [ 10 , 11 ] assert that stigmatizing higher-weight individuals and applying social pressure to incite weight loss improves population health. We argue the opposite. The latest science indicates that weight stigma can trigger physiological and behavioral changes linked to poor metabolic health and increased weight gain [ 4 , 5 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. In laboratory experiments, when study participants are manipulated to experience weight stigma, their eating increases [ 15 , 16 ], their self-regulation decreases [ 15 ], and their cortisol (an obesogenic hormone) levels are higher relative to controls, particularly among those who are or perceive themselves to be overweight. Additionally, survey data reveal that experiences with weight stigma correlate with avoidance of exercise [ 17 ]. The long-term consequences of weight stigma for weight gain, as this experimental and survey work suggests, have also been found in large longitudinal studies of adults and children, wherein self-reported experiences with weight stigma predict future weight gain and risk of having an ‘obese’ BMI, independent of baseline BMI [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

The harmful effects of weight stigma may even extend to all-cause mortality. Across both the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study including 13,692 older adults and the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study including 5079 adults, people who reported experiencing weight discrimination had a 60% increased risk of dying, independent of BMI [ 21 ]. The underlying mechanisms explaining this relationship, which controls for BMI, may reflect the direct and indirect effects of chronic social stress. Biological pathways include dysregulation in metabolic health and inflammation, such as higher C-reactive protein, among individuals who experience weight discrimination [ 22 ]. In MIDUS and other studies, weight discrimination also amplified the relationship between abdominal obesity and HbA1c, and metabolic syndrome more generally [ 23 , 24 ]. Longitudinal data from MIDUS also showed that weight discrimination exacerbated the effects of obesity on self-reported functional mobility, perhaps because weight discrimination undermines one’s self-concept as a fully functioning, able person [ 25 ].

Weight stigma also has profound negative effects on mental health; nationally representative data from the United States show that individuals who perceive that they have been discriminated against on the basis of weight are roughly 2.5 times as likely to experience mood or anxiety disorders as those that do not, accounting for standard risk factors for mental illness and objective BMI [ 26 ]. Furthermore, this detrimental effect of weight stigma on mental health is not limited to the United States; weight-related rejection has also been shown to predict higher depression risk in other countries [ 27 ]. Importantly, the evidence indicates that the association generally runs from discrimination to poor mental health, rather than vice versa [ 27 ].

A rapidly growing set of studies now shows that these associations cannot simply be explained by higher-weight individuals’ poorer health or greater likelihood of perceiving weight-related discrimination. In fact, the mere perception of oneself as being overweight, across the BMI spectrum (i.e., even among individuals at a ‘normal’ BMI), is prospectively associated with biological markers of poorer health, including unhealthy blood pressure, C-reactive protein, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and HbA1c levels [ 28 ]. Emerging evidence indicates that this harmful cycle may even be intergenerational, wherein children perceived as overweight by their parents are at greater risk for excess weight gain across childhood [ 29 ], independent of the child’s actual weight. Collectively, these findings suggest that stigma attached to being ‘overweight’ is a significant yet unrecognized agent in the causal pathway from weight status to health.

Weight stigma in healthcare

Healthcare is a setting in which weight stigma is particularly pervasive, with significant consequences for the health of higher-weight patients [ 30 , 31 ]. A sample of 2284 physicians showed strong explicit and implicit ‘anti-fat’ bias [ 32 ]. High levels of bias are observed even among clinicians specializing in obesity-related issues, with the proportion endorsing explicit ‘anti-fat’ bias sentiments (e.g., ‘Fat people are worthless’) increasing in recent years [ 33 ]. The nature of healthcare provider bias encompasses endorsement of negative stereotypes of patients with obesity, including terms like ‘lazy’, ‘weak-willed’, and ‘bad’, feeling less respect for those patients, and being more likely to report them as a ‘waste of time’ [ 30 ].

This stigma has direct and observable consequences for the quality and nature of services provided to those with obesity, leading to yet another potential pathway through which weight stigma may contribute to higher rates of poor health. In terms of quality of care and medical decision-making, despite the fact that higher-weight patients are at elevated risk for endometrial and ovarian cancer, some physicians report a reluctance to perform pelvic exams [ 34 ] and higher-weight patients (despite having health insurance) delay having them [ 35 ]. Higher BMI male patients report that physicians spend less time with them compared to the time they spend with lower BMI patients [ 36 ]. Additionally, physicians engage in less health education with higher BMI patients [ 37 ].

In terms of quality of communication, higher-weight patients are clearly receiving the message that they are unwelcome or devalued in the clinical setting, frequently reporting feeling ignored and mistreated in clinical settings, and higher BMI adults are nearly three times as likely as persons with ‘normal’ BMI to say that they have been denied appropriate medical care [ 38 ]. Further, obese patients feel that their clinicians would prefer not to treat them [ 36 ]. As a result, patients with higher BMI report avoiding seeking healthcare because of the discomfort of being stigmatized [ 35 , 39 , 40 ]. Even when they do seek medical care, weight loss attempts are less successful when patients perceive that their primary care providers judge them on the basis of their weight [ 41 ].

Medical professionals are also not immune to experiencing weight bias. Medical students with a higher BMI report that clinical work can be particularly challenging, and those with a higher BMI who internalize ‘anti-fat’ attitudes also report more depressive symptoms and alcohol or substance abuse [ 42 ].

Tackling weight stigma

Many common anti-obesity efforts are unintentionally complicit in contributing to weight stigma. Standard medical advice for weight loss focuses on taking individual responsibility and exerting willpower (‘eat less, exercise more’). In this context, a little shame is seen as motivation to change diet and activity behaviors [ 10 , 11 ]. Nevertheless, this approach perpetuates stigmatization, as higher-weight individuals already engage in self-blame [ 43 ] and feel ashamed of their weight [ 44 ]. Stigma, therefore, maybe be an unintended consequence of anti-obesity efforts, undermining their intended effect. Moreover, focusing solely on obesity treatment runs the risk of missing other diagnoses, as was recently illustrated by Rebecca Hiles, whose multiple physicians failed to diagnose her lung cancer and instead repeatedly told her to lose weight in order to address her shortness of breath [ 45 ].

Traditional approaches to combatting obesity and poor metabolic health are clearly not working. Obesity rates remain high globally in both adults [ 46 , 47 ] and children [ 48 ], and even in those countries where rates appear to be plateauing, disparities continue to grow between dominant and minority groups (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities, lower socioeconomic status populations, and those with the highest BMI) [ 49 , 50 , 51 ]. Moreover, given the link between obesity, metabolic health, and stigma, the need to eradicate weight stigma is urgent. Metabolic diseases such as type II diabetes are at unprecedented levels in adults and children [ 52 ]. Governments and clinicians alike have struggled to find effective strategies to prevent weight gain, support weight loss, and promote metabolic health. The science of weight stigma crystallizes a key point for future success – to tackle the obesity ‘epidemic’ we must tackle the parallel epidemic of weight stigma.

The most effective and ethical approaches will aim to address the behaviors and attitudes of the individuals and institutions that do the stigmatizing, rather than those of the targets of mistreatment [ 53 ], thus avoiding blaming the victim and removing the burden of change from those experiencing mistreatment. Such a pervasive problem requires a multi-pronged strategy both within healthcare settings and at higher levels of government and society. In healthcare settings, medical training must address weight bias. Healthcare professionals and students need to be educated about what weight bias is, how it is perpetuated, the subtle ways it manifests, and the effect that it has on their patients. Part of this training could include education regarding the research documenting the complex relationship between higher BMI and health [ 54 ], the well-documented shortcomings of BMI as an indicator of health [ 55 , 56 ], and important non-behavioral contributors to BMI such as genes [ 57 ] and diseases that create obesity as a symptom (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome, lipedema, or hypothyroidism). Compassionate and knowledgeable healthcare providers will deliver better care, lessening the negative effects of weight bias. However, healthcare providers could go beyond merely not having bias to creating weight-inclusive [ 58 ], welcoming atmospheres. Such an approach focuses on well-being rather than weight loss and emphasizes healthy behaviors [ 13 , 58 ]. Empathy, respect, and humanity will foster better healthcare.

At a broader level, public health approaches to promoting metabolic health must stop the blame and shame implicit (and sometimes very explicit [ 59 ]) in their messaging. Public health messages speak not just to the target of the message but also to society more generally. Fat-shaming messages encourage discrimination by condoning it. Public health messages can encourage healthy behaviors without once mentioning weight or size by emphasizing that modifiable behaviors, such as an increase in fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity, better sleep patterns, and stress reduction, would improve health for all [ 13 , 60 , 61 ], regardless of the number on the scale.

Furthermore, there must be legal protection against weight-based discrimination. In the United States, for example, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not identify weight as a protected characteristic, and only in rare instances can people with very high BMI seek legal protection under Americans with Disabilities Act legislation. Drawing parallels from analyses of sexual orientation discrimination laws [ 26 ], we know that policies protecting higher-weight individuals will reduce the likelihood that prejudicial beliefs against stigmatized people are translated into damaging discriminatory treatment.

Influential people who fat shame, whether they are healthcare providers, parents, educators, business leaders, celebrities, or politicians, are the most damaging. They must be made aware of and held responsible for their behavior. Social attitudes likely change fastest when those with the most power serve as proper role models for a civil society or face negative consequences of their demeaning behavior [ 62 , 63 ]. However, who will call out those that are enacting prejudice? Healthcare providers may be ideal candidates to do so. Higher status individuals incur fewer social costs than lower status individuals when they recognize and claim discrimination happening to others [ 64 ]. Healthcare providers are conferred higher social status due to the imprimatur of medicine, and can thus serve as valuable allies for heavier individuals facing fat shaming.

Finally, public service messages are needed to educate people about the stigma, discrimination, and challenges facing higher-weight individuals; blatant discrimination must be stopped, but so too must the implicit [ 33 ] and daily [ 65 , 66 ] cultural biases against them. Weight stigma often happens in quiet and subtle ways that may be invisible to those doing the stigmatizing, yet hurtful and demoralizing to those on the receiving end. For example, a thinner patient may receive eye contact and a smile from a physician who walks into the room, whereas that same physician might avoid eye contact with a heavier patient; the daily nature of this form of weight stigma likely accumulates, ultimately harming health [ 67 ].

We have argued in this Opinion article that weight stigma poses a threat to health. There is a clear need to combat weight stigma, which is widespread worldwide [ 3 ] and, as we reviewed above, throughout healthcare settings. Doing so will help to improve the health and quality of life of millions of people. Indeed, eradicating weight stigma will likely improve the health of all individuals, regardless of their size, since the insidious effects of weight stigma reviewed herein are found independently of objective BMI, with many individuals with ‘normal’ BMI also falling prey to the health-harming processes brought about by weight stigmatization.

Enlightened societies should not treat its members with prejudice and discrimination because of how they look. Healthcare providers should treat obesity if patients have actual markers of poor metabolic health rather than simply due to their high BMI. Additionally, if patients request counseling regarding their metabolic health, healthcare providers can address actual behaviors, such as healthy eating and physical activity, without ever mentioning, and certainly without ever stigmatizing, a patient’s objective BMI [ 13 ]. Indeed, this is the strategy of interventions such as Health at Every Size ® [ 68 ] and other non-dieting approaches (reviewed in [ 69 ]), which have been shown in randomized controlled trials to improve multiple health outcomes such as blood pressure and cholesterol. The provider–patient relationship is one that is inherently unequal, with healthcare providers holding the power to profoundly affect patient’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors [ 70 ]. To advance as an equal society, healthcare providers should lead the way for weight stigma eradication.

Abbreviations

Body mass index

Midlife in the United States

Richardson SA, Goodman N, Hastorf AH, Dornbusch SM. Cultural uniformity in reaction to physical disabilities. Am Sociol Rev. 1961;26(2):241–7.

Article Google Scholar

Andreyeva T, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Changes in perceived weight discrimination among Americans, 1995-1996 through 2004-2006. Obesity. 2008;16(5):1129–34.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brewis AA, Wutich A, Falletta-Cowden A, Rodriguez-Soto I. Body norms and fat stigma in global perspective. Curr Anthropol. 2011;52(2):269–76.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009;17(5):941–64.

Puhl RM, Suh Y. Health consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(2):182–90.

Spahlholz J, Baer N, König H-H, Riedel-Heller SG, Luck-Sikorski C. Obesity and discrimination - a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes Rev. 2016;17(1):43–55.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Puhl RM, Andreyeva T, Brownell KD. Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obes. 2008;32(6):992–1000.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fikkan JL, Rothblum ED. Is fat a feminist issue? Exploring the gendered nature of weight bias. Sex Roles. 2012;66(9):575–92.

Phelan SM, Dovidio JF, Puhl RM, et al. Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: the medical student CHANGES study. Obesity. 2014;22(4):1201–8.

Callahan D. Obesity: chasing an elusive epidemic. Hast Cent Rep. 2013;43(1):34–40.

Callahan D. Children, stigma, and obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(9):791–2.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1019–28.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Logel C, Stinson DA, Brochu PM. Weight loss is not the answer: a well-being solution to the “obesity problem”. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2015;9(12):678–95.

Major B, Tomiyama AJ, Hunger JM. The negative and bidirectional effects of weight stigma on health. In: Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health; 2018. p. 499–519.

Google Scholar

Major B, Hunger JM, Bunyan DP, Miller CT. The ironic effects of weight stigma. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2014;51:74–80.

Schvey NA, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. The impact of weight stigma on caloric consumption. Obesity. 2011;19(10):1957–62.

Vartanian LR, Shaprow JG. Effects of weight stigma on exercise motivation and behavior: a preliminary investigation among college-aged females. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(1):131–8.

Hunger JM, Tomiyama AJ. Weight labeling and obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(6):579–80.

Jackson SE, Beeken RJ, Wardle J. Perceived weight discrimination and changes in weight, waist circumference, and weight status. Obesity. 2014;22:2485–8.

Sutin AR, Terracciano A. Perceived weight discrimination and obesity. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70048.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(11):1803–11.

Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Terracciano A. Perceived weight discrimination and C-reactive protein. Obesity. 2014;22(9):1959–61.

Tsenkova V, Carr D, Schoeller D, Ryff C. Perceived weight discrimination amplifies the link between central adiposity and nondiabetic glycemic control (HbA1c). Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):243–51.

Pearl RL, Wadden TA, Hopkins CM, et al. Association between weight bias internalization and metabolic syndrome among treatment-seeking individuals with obesity. Obesity. 2017;25(2):317–22.

Schafer MH, Ferraro KF. The stigma of obesity. Soc Psychol Q. 2011;74(1):76–97.

Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Associations between perceived weight discrimination and the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the general population. Obesity. 2009;17(11):2033–9.

Hackman J, Maupin J, Brewis AA. Weight-related stigma is a significant psychosocial stressor in developing countries: evidence from Guatemala. Soc Sci Med. 2016;161:55–60.

Daly M, Robinson E, Sutin AR. Does knowing hurt? Perceiving oneself as overweight predicts future physical health and well-being. Psychol Sci. 2017;28(7):872–81.

Robinson E, Sutin AR. Parental perception of weight status and weight gain across childhood. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153957.

Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):319–26.

Puhl RM, Phelan SM, Nadglowski J, Kyle TK. Overcoming weight bias in the management of patients with diabetes and obesity. Clin Diabetes. 2016;34(1):44–50.

Sabin JA, Marini M, Nosek BA. Implicit and explicit anti-fat bias among a large sample of medical doctors by BMI, race/ethnicity and gender. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48448.

Tomiyama AJ, Finch LE, Belsky ACI, et al. Weight bias in 2001 versus 2013: contradictory attitudes among obesity researchers and health professionals. Obesity. 2015;23(1):46–53.

Adarns CH, Smith NJ, Wilbur DC, Grady KE. The relationship of obesity to the frequency of pelvic examinations: do physician and patient attitudes make a difference? Women Health. 1993;20(2):45–57.

Amy NK, Aalborg A, Lyons P, Keranen L. Barriers to routine gynecological cancer screening for white and African-American obese women. Int J Obes. 2006;30(1):147–55.

Hebl MR, Xu J, Mason MF. Weighing the care: patients’ perceptions of physician care as a function of gender and weight. Int J Obes. 2003;27(2):269–75.

Bertakis KD, Azari R. The impact of obesity on primary care visits. Obes Res. 2005;13(9):1615–23.

Carr D, Friedman MA. Is obesity stigmatizing? Body weight, perceived discrimination, and psychological well-being in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(3):244–59.

Puhl RM, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Parental perceptions of weight terminology that providers use with youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):e786–93.

Puhl RM, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Motivating or stigmatizing? Public perceptions of weight-related language used by health providers. Int J Obes. 2013;37(4):612–9.

Gudzune KA, Bennett WL, Cooper LA, Bleich SN. Perceived judgment about weight can negatively influence weight loss: a cross-sectional study of overweight and obese patients. Prev Med (Baltim). 2014;62:103–7.

Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Puhl RM, et al. The adverse effect of weight stigma on the well-being of medical students with overweight or obesity: findings from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1251–8.

Puhl RM, Moss-Racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Weight stigmatization and bias reduction: perspectives of overweight and obese adults. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(2):347–58.

Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA, Noll SM, Quinn DM, Twenge JM. That swimsuit becomes you: sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75(1):269–84.

Dusenbery M. Doctors told her she was just fat. She actually had cancer. Cosmopolitan. 2018. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/health-fitness/a19608429/medical-fatshaming/ . Accessed 26 June 2018.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377–96.

Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–42.

GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27.

Krueger PM, Reither EN. Mind the gap: race/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in obesity. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(11):95.

Frederick CB, Snellman K, Putnam RD. Increasing socioeconomic disparities in adolescent obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(4):1338–42.

Mensink GBM, Schienkiewitz A, Haftenberger M, Lampert T, Ziese T, Scheidt-Nave C. Übergewicht und Adipositas in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforsch - Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(5–6):786–94.

Moore JX, Chaudhary N, Akinyemiju T. Metabolic syndrome prevalence by race/ethnicity and sex in the United States, National Health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:160287.

Pearl RL. Weight bias and stigma: public health implications and structural solutions. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2018;12(1):146–82.

Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309(1):71–82.

Tomiyama AJ, Hunger JM, Nguyen-Cuu J, Wells C. Misclassification of cardiometabolic health when using body mass index categories in NHANES 2005-2012. Int J Obes. 2016;40(5):883–6.

Rothman KJ. BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. Int J Obes. 2008;32:S56–9.

Bell CG, Walley AJ, Froguel P. The genetics of human obesity. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(3):221–34.

Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, et al. The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. J Obes. 2014;2014:983495.

Teegardin C. Grim childhood obesity ads stir critics. The Atlanta Journal Constitution. 2012. https://www.ajc.com/news/local/grim-childhood-obesity-ads-stir-critics/GVsivE43BYQAqe6bmufd7O/ . Accessed 26 June 2018.

Chiang JJ, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, Miller GE. Affective reactivity to daily stress and 20-year mortality risk in adults with chronic illness: findings from the National Study of daily experiences. Health Psychol. 2018;37(2):170–8.

Carroll JE, Seeman TE, Olmstead R, et al. Improved sleep quality in older adults with insomnia reduces biomarkers of disease risk: pilot results from a randomized controlled comparative efficacy trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;55:184–92.

Dasgupta N, Greenwald AG. On the malleability of automatic attitudes: combating automatic prejudice with images of admired and disliked individuals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81(5):800–14.

French JRP, Raven B. The bases of social power. In: Cartwright D, editor. Studies in social power. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 1959. p. 150–67.

Eliezer D, Major B. It’s not your fault: the social costs of claiming discrimination on behalf of someone else. Gr Process Intergr Relat. 2012;15(4):487–502.

Seacat JD, Dougal SC, Roy D. A daily diary assessment of female weight stigmatization. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(2):228–40.

Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT, Smyth JM. The phenomenology of weight stigma in everyday life. J Context Behav Sci. 2014;3(3):196–202.

Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT, Smyth JM. Experiences of weight stigma in everyday life: implications for health motivation. Stigma Heal. 2018;3(2):85–92.

Bacon L. Health at every size: the surprising truth about your weight. Dallas: BenBella Books Inc.; 2008.

Bacon L, Aphramor L. Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J. 2011;10(1):9.

Hall JA, Roter DL. Physician–patient communication. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford handbook of Health Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust and Mayo Clinic-ASU Obesity Solutions for supporting the workshop that that allowed us to work together on this piece.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of California Los Angeles, 1285 Franz Hall, Los Angeles, CA, 90095, USA

A. Janet Tomiyama

Department of Sociology, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA

Deborah Carr

Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminal Justice, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA

Ellen M. Granberg

Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA

Brenda Major

Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Eric Robinson

Department of Behavioral Sciences and Social Medicine, Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, FL, USA

Angelina R. Sutin

School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Alexandra Brewis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AJT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Authors are listed alphabetically aside from the first and last authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to A. Janet Tomiyama .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tomiyama, A., Carr, D., Granberg, E. et al. How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Med 16 , 123 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1116-5

Download citation

Received : 12 March 2018

Accepted : 03 July 2018

Published : 15 August 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1116-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Weight stigma

- Weight bias

- Anti-fat attitudes

- Discrimination

- Health policy

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity

Wl hellerstedt.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr SM Phelan, Division of Health Care Policy and Research, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA., E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2014 Oct 25; Revised 2014 Dec 19; Accepted 2015 Jan 7; Issue date 2015 Apr.

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.

The objective of this study was to critically review the empirical evidence from all relevant disciplines regarding obesity stigma in order to (i) determine the implications of obesity stigma for healthcare providers and their patients with obesity and (ii) identify strategies to improve care for patients with obesity. We conducted a search of Medline and PsychInfo for all peer-reviewed papers presenting original empirical data relevant to stigma, bias, discrimination, prejudice and medical care. We then performed a narrative review of the existing empirical evidence regarding the impact of obesity stigma and weight bias for healthcare quality and outcomes. Many healthcare providers hold strong negative attitudes and stereotypes about people with obesity. There is considerable evidence that such attitudes influence person-perceptions, judgment, interpersonal behaviour and decision-making. These attitudes may impact the care they provide. Experiences of or expectations for poor treatment may cause stress and avoidance of care, mistrust of doctors and poor adherence among patients with obesity. Stigma can reduce the quality of care for patients with obesity despite the best intentions of healthcare providers to provide high-quality care. There are several potential intervention strategies that may reduce the impact of obesity stigma on quality of care.

Keywords: Delivery of health care, obesity, stereotyping, social stigma

Introduction

The goal of primary care is to improve patients' health, longevity and quality of life through the provision of patient-centred care. To do so, healthcare providers must identify modifiable behaviours that increase disease risk, and help patients change them. Recent US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines recommend screening adults for obesity and offering behavioural interventions to those with a body mass index (BMI) over 30 kg m −2 ( 1 ). However, obesity is a stigmatized condition; thus, one side effect of increased focus on body weight in health care may be the alienation and humiliation of these patients. The term ‘stigma’ describes physical characteristics or character traits that mark the bearer as having lower social value ( 2 ). A stigmatized trait can lead to experiences of discrimination, and the feeling of being stigmatized can put one at risk for low self-esteem ( 3 ), depression ( 4 – 6 ) and lower quality of life ( 7 – 10 ). However, the empirical evidence on stigma overall and obesity stigma in particular is scattered across diverse disciplines and lines of research, making it difficult to get a clear picture of the implication of obesity stigma for healthcare providers and their patients.

In order to address this gap, we critically reviewed literature related to the impact of obesity stigma on interpersonal encounters and decision-making. We discuss potential implications, including several mechanisms whereby stigma may affect patient-centred communication and care, defined by the Institute of Medicine ( 11 ) as ‘care that establishes a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients' wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care’ (p. 7). We also suggest several strategies that may help healthcare providers and clinics reduce the impact of stigma on patients with obesity.

Obesity is a commonly and strongly stigmatized characteristic ( 12 , 13 ). There is substantial empirical evidence that people with obesity elicit negative feelings such as disgust, anger, blame and dislike in others ( 14 – 16 ). Despite the high prevalence of obesity (approximately one-third of the US adult population ( 17 ) ), individuals with obesity are frequently the targets of prejudice, derogatory comments and other poor treatment in a variety of settings, including health care ( 12 , 18 ). Furthermore, there is a growing body of evidence that physicians and other healthcare professionals hold strong negative opinions about people with obesity ( 19 – 27 ).

We conducted a narrative review of this literature to highlight the ways that the obesity stigma may interrupt the healthcare process and impede many healthcare providers' goal of providing equitable high-quality care. We reviewed all original studies in the fall of 2014 on topics related to obesity stigma in medical care and/or the impact of stigma on interpersonal encounters and decision-making in PubMed and PsychInfo, with the majority of studies found in health communication, social psychology and health disparities research. We then selected papers relevant to the potential impact of obesity stigma on healthcare provider behaviour, patient healthcare outcomes and healthcare encounters.

Impact on providers

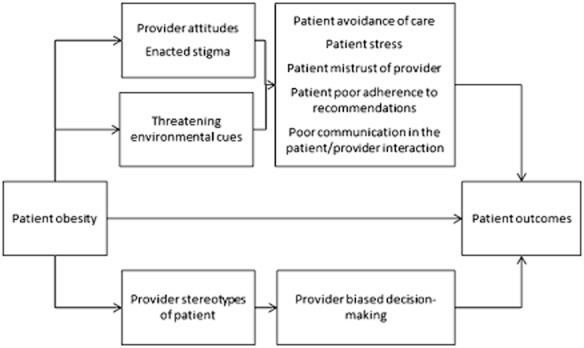

Primary care providers and health promotion specialists, who typically demonstrate a commitment to providing care for underserved populations, are unlikely to flagrantly and intentionally discriminate against their patients. Nevertheless, there are several ways that their attitudes about obesity may cause their patients with obesity to feel disrespected, inadequate or unwelcome, thus negatively affecting the encounter quality and their willingness to seek needed care (see Fig. 1 ). Behaviours that emanate from negative attitudes about a stigmatized group are known as enacted stigma ( 28 ). Enacted stigma on the part of the provider affects the patient in both measurable and immeasurable ways. It can reduce the quality, and even the quantity, of patient-centred care, and can signal to the patient that he or she is being perceived in terms of his or her stigmatized identity, which, in turn, may affect patient perception of, and compliance with, provider recommendations.

A conceptual model of hypothesized pathways whereby the associations between obesity and health outcomes are partially mediated by healthcare providers' attitudes and behaviours about obese patients, and patients' response to feeling stigmatized.

The negative attitudes underlying enacted stigma can be explicit or implicit. Explicit attitudes are conscious and reflect a person's opinions or beliefs about a group. Implicit attitudes are automatic and often occur outside of awareness and in contrast to explicitly held beliefs ( 29 ). The response to some stigmatized groups, such as racial minorities among egalitarian Caucasians, often consists of negative implicit attitudes, but neutral or positive explicit ones ( 30 ). In contrast, explicit negative attitudes about people with obesity are more socially acceptable than explicit racism: e.g. it is acceptable in many Western cultures that people with obesity are the source of derogatory humour and may thus be openly – and unquestionably – portrayed as lazy, gluttonous and undisciplined. Primary care providers, medical trainees, nurses and other healthcare professionals hold explicit as well as implicit negative opinions about people with obesity ( 21 , 31 – 33 ). This has important implications for communication in the clinical interview, because explicit attitudes influence verbal behaviours as well as decisions that are within conscious control, whereas implicit negative attitudes predict non-verbal communication and decisions under cognitive burden ( 29 , 34 – 36 ). There is evidence that providers' communication is less patient-centred with members of stigmatized racial groups ( 37 – 43 ), and other stigmatized groups including patients with obesity ( 44 ), and that provider attitudes contribute to this disparity ( 45 – 47 ). Implicit attitudes have also been found to be associated with lower patient ratings of care ( 46 ). The combination of implicit and explicit negative obesity attitudes may elevate the potential for impaired patient-centred communication, which is associated with a 19% higher risk of patient non-adherence, as well as mistrust, and worse patient weight loss, recovery and mental health outcomes ( 48 – 53 ).

There are several mechanisms by which provider attitudes may affect the quality of, or potential for, patient-centred care. First, primary care providers engage in less patient-centred communication with patients they believe are not likely to be adherent ( 54 ). A common explicitly endorsed provider stereotype about patients with obesity is that they are less likely to be adherent to treatment or self-care recommendations ( 23 , 24 , 55 , 56 ), are lazy, undisciplined and weak-willed ( 12 , 55 , 57 – 59 ). Second, primary care providers have reported less respect for patients with obesity compared with those without ( 59 , 60 ), and low respect has been shown to predict less positive affective communication and information giving ( 61 ). Third, primary healthcare providers may allocate time differently, spending less time educating patients with obesity about their health ( 62 ). For example, in one study of primary care providers randomly assigned to evaluate the records of patients who were either obese or normal weight, providers who evaluated patients who were obese were more likely to rate the encounter as a waste of time and indicated that they would spend 28% less time with the patient compared with those who evaluated normal-weight patients ( 59 ). Finally, physicians may over-attribute symptoms and problems to obesity, and fail to refer the patient for diagnostic testing or to consider treatment options beyond advising the patient to lose weight. In one study involving medical students, virtual patients with shortness of breath were more likely to receive lifestyle change recommendations if they were obese (54% vs. 13%), and more likely to receive medication to manage symptoms if they were normal weight (23% vs. 5%) ( 23 ).

Impact on patients

Experiences of discrimination and awareness of stigmatized social status can cause patients to experience stress and have other acute reactions that may reduce the quality of the encounter, regardless of their provider's attitudes and behaviour. Three conceptually overlapping processes – identity threat, stereotype threat and felt stigma – describe the stigmatized patient's reaction to being stigmatized. Identity threat occurs when patients experience situations that make them feel devalued because of a social identity. Social identities are the categories, roles, and social groups that define each person and give a sense of self ( 63 , 64 ). Each social identity, be it a professional identity, a gender identity, or identity as a person who is obese, has emotional significance for the individual, is closely tied to self-esteem, and can empower or make one vulnerable. Obesity is stigmatized, and thus is more likely to make the individual aware of the possibility for rejection or derogation than make him/her feel confident and empowered. Stereotype threat occurs when an individual is aware that he or she may be viewed as a member of a stigmatized group, and becomes preoccupied with detecting stereotyping on the part of the provider and monitoring his or her own behaviour to ensure that it does not confirm group stereotypes ( 65 ). Felt stigma is a term used to describe the expectation of poor treatment based on past experiences of discrimination ( 28 ).

The effects of stigma are both immediate and long-term. The direct effects of provider attitudes on patient-centred care may reduce the quality of the patient encounter, harming patient outcomes and reducing patient satisfaction. Patients with obesity who experience identity/stereotype threat or felt/enacted stigma may experience a high level of stress which can contribute to impaired cognitive function and ability to effectively communicate ( 66 ). Accumulated exposure to high levels of stress hormones (allostatic load) has several long-term physiological health effects, including heart disease, stroke, depression and anxiety disorder, diseases that disproportionately affect obese individuals and have been empirically linked to perceived discrimination ( 67 – 69 ). Indeed, stress pathways may present an alternate explanation for some proportion of the association between obesity and chronic disease ( 70 ).

Other effects include avoidance of clinical care if patients perceive that their body weight will be a source of embarrassment in that setting ( 71 , 72 ). For example, there is evidence that obese women are less likely to seek recommended screening for some cancers ( 72 – 76 ). The long-term result of avoidance and postponement of care is that people with obesity may present with more advanced, and thus more difficult to treat, conditions. Individuals who are stigmatized, or are vigilant for evidence of stigma, may withdraw from full participation in the encounter. Because of this, they may not recall advice or instructions given by the provider, reducing adherence to prescribed treatment or self-care. Experiencing stereotype threat may also cause patients to discount feedback provided by the source of the threat ( 77 ), which in turn may affect adherence. Patients who report feeling judged by their primary care provider are less likely to seek or achieve successful weight loss ( 78 , 79 ). Patients who have tried to lose weight and failed may ‘dis-identify’, or reduce their efforts to lose weight, in order to disconnect their self-esteem from achievement in a domain with which they have not had success ( 65 ), and may feel shame for failing to lose weight or maintain weight loss ( 78 ). Along similar lines, individuals who experience more obesity stigma report less health utility, or place lower value on health ( 80 ).

Setting factors